TL;DR

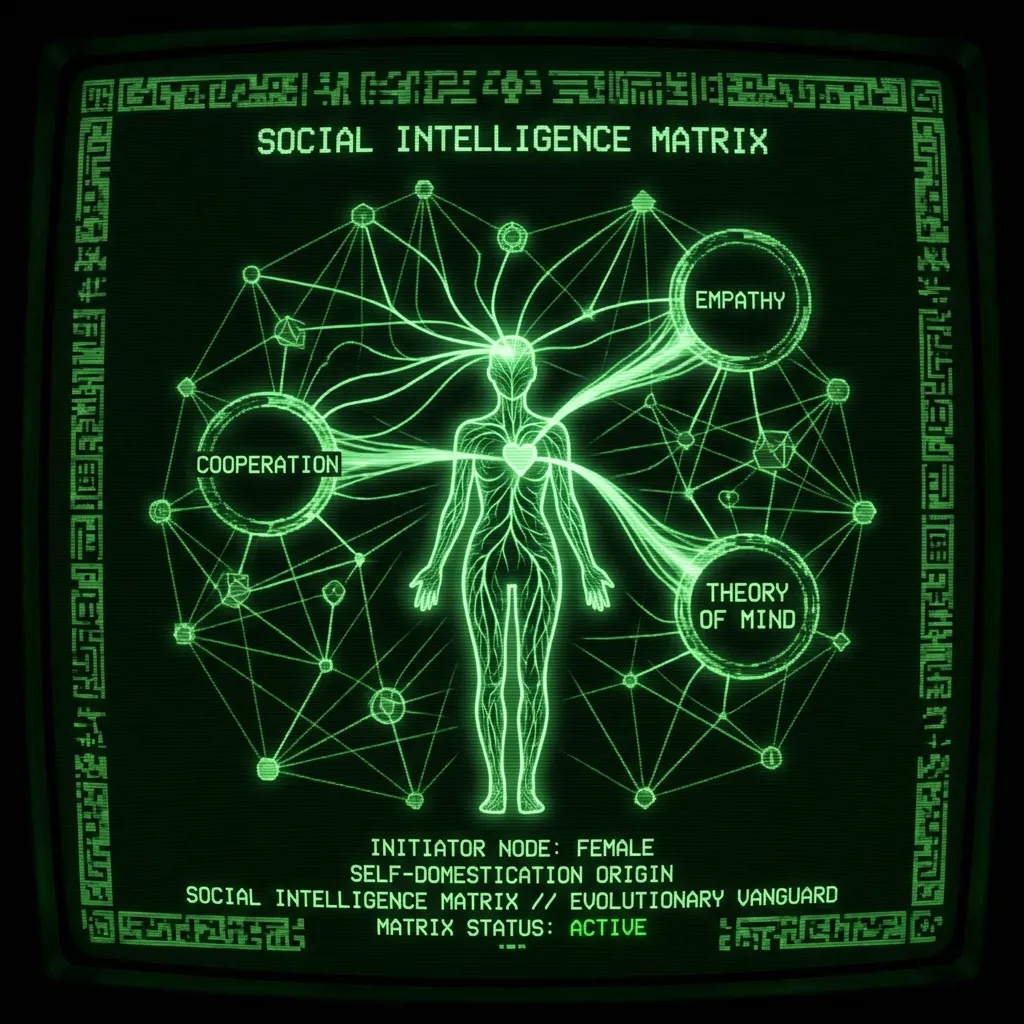

- Social intelligence and prosociality (self-domestication) were key drivers of human evolution.

- Evolutionary pressures for these traits likely acted earlier and more strongly on females due to demands of maternal care, cooperative breeding, and social dynamics.

- Mothers, grandmothers, and female coalitions were pivotal in enhancing empathy, cooperation, and taming aggression, shaping the human social mind.

- Consequently, women arguably spearheaded the evolution of uniquely human social intelligence, acting as the “evolutionary vanguard.”

Introduction#

If advanced social intelligence – our species’ capacity for empathy, mind-reading, and cooperative self-control – is what truly made us human, then it stands to reason that women were “human” first.

This provocative thesis is not an ideological slogan but an evolutionary hypothesis: that females, especially mothers and grandmothers, were the evolutionary vanguard of social cognition and the initiating edge of the self-domestication process that gave rise to Homo sapiens. In plainer terms, the selective pressures favoring empathy, theory of mind, emotional regulation, and prosocial behavior may have acted earlier and more intensively on females, making women the first to develop the quintessentially human social mind.

This report rigorously examines this idea through evidence and logic – eschewing wishful thinking or activist framing – to show why female-led selection pressures were likely indispensable in human evolution. We focus on how maternal caregiving, alloparental cooperation, and female social choices created the preconditions for humanity’s unique self-domestication, and we address potential counterarguments directly. The goal is a truth-first, precise analysis of why, if social intelligence made us human, women indeed blazed that trail.

Social Intelligence: The Human Trademark#

Human beings are often defined by their extraordinary social intelligence. We live in complex societies that demand understanding others’ intentions, coordinating group actions, and curbing antisocial impulses. Evolutionary anthropologists argue that our large brains evolved not just for tool use, but primarily to handle the demands of social life – an idea known as the social brain or Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis [^1].

Note: The footnote markers

[^N]in the text above are placeholders. The full bibliography with corresponding links can be found at: https://chatgpt.com/share/68055003-1674-8008-92a0-85bbddae351a

Compared to other apes, humans excel at theory of mind (inferring what others know, want, or intend) and at forming shared goals and cultures. For example, human children can intuit others’ desires and share intentions in ways our closest ape relatives (chimpanzees) generally do not [^2]. This suite of capabilities – from empathy and communication to strategic alliance formation – constitutes the social cognition that underpins language, teaching, and cooperation. In short, being “human” is largely about being socially smart.

Importantly, these social skills did not arise in a vacuum; they were favored by natural selection because they conferred survival and reproductive advantages. Early humans that could cooperate in hunting and gathering, resolve conflicts peaceably, or support each other in times of need would outcompete more solitary or aggressive groups [^3]. Paleoanthropological evidence suggests that as our lineage evolved, individuals with greater social adeptness had higher fitness.

Cognitive scientists note that humans have neurobiological specializations for social learning and communication – evidence that social challenges shaped our brains. Indeed, the emergence of Homo sapiens (~300,000 years ago) appears associated with a shift toward more prosocial, group-oriented behavior [^4]. The thesis “social intelligence made us human” means these abilities were the critical differentiator setting our ancestors on a unique evolutionary path.

But if social intelligence was the engine, we must ask: were there differences between the sexes in how and when this engine revved up? Evolution often places distinct pressures on males and females due to their differing reproductive roles. We will argue that the selection pressures for advanced social cognition were especially acute for females – in particular, mothers and alloparents – because of the demands of raising highly dependent offspring and maintaining cohesive communities. Over generations, this led females to pioneer the “humanness” of high-level social intelligence, dragging the species forward into a new adaptive zone. Before detailing that, we introduce a crucial concept linking social intelligence to human evolution: self-domestication.

The Self-Domestication Hypothesis: Taming Ourselves#

Humans possess puzzling traits that resemble those of domesticated animals (like dogs or cows) compared to their wild ancestors. Charles Darwin long ago noted that domesticated mammals share certain features – a “domestication syndrome” – including tameness, juvenile-like behavior, reduced aggression, and even physical changes like smaller teeth or altered skull shape [^5][^6].

In the last two decades, researchers have proposed that Homo sapiens underwent an analogous process of self-domestication, in which natural selection favored more docile, prosocial individuals over aggressive, “wild” ones [^7][^8]. In effect, our ancestors “tamed” themselves by weeding out hyper-aggressive tendencies and amplifying social tolerance within groups.

This idea is supported by anatomical evidence: compared to earlier hominins (and especially compared to Neanderthals), modern humans have gracile, childlike features – for instance, a reduction in brow ridge prominence and overall facial robusticity [^9][^10]. Archaeologists find that by around 300,000 years ago, early H. sapiens skulls already show a shorter face, smaller teeth, and reduced brow-ridges relative to predecessors [^11]. All these are hallmarks of domestication. In fact, one survey identified H. sapiens fossils with “feminized” skulls – smaller, with less male-male combat ornamentation – as the earliest truly modern humans [^12].

Modern human (left) vs. Neanderthal (right) skulls, illustrating the flatter face and reduced brow ridge of self-domesticated Homo sapiens.

The self-domestication hypothesis holds that becoming friendlier and more cooperative was a winning strategy in human evolution. By selecting against reactive aggression (impulsive violence) and for impulse control, empathy, and in-group prosociality, our ancestors achieved greater group harmony and possibly new cognitive heights [^13][^14]. One can think of this as an evolutionary “civilizing” process – not imposed by any external breeder, but arising naturally because groups of more socially tolerant individuals thrived and left more descendants.

Supporting this, genetic studies and comparisons to domesticated animals suggest changes in genes (like those affecting neural crest cells) that could make human temperament calmer and our faces more juvenilized [^15][^16]. In essence, by the late Pleistocene our lineage had become a “domesticated ape” – more emotionally balanced and group-oriented than our fiercer hominin cousins.

Crucially, self-domestication is not just about being nice; it directly relates to social intelligence. A less aggressive, more tolerant individual can afford to engage in deeper social learning and collaboration. Reduced aggression likely opened the door for enhanced communication and empathy – you can’t easily teach or learn from someone who might attack you.

Researchers argue that selection for tameness in humans brought along greater capacity for shared intentionality (truly sharing goals and knowledge) [^17][^18]. This is because once our ancestors were inclined to trust and tolerate one another, the existing cognitive abilities inherited from apes could be repurposed from competitive trickery to cooperative thinking [^19][^20]. In short, self-domestication amplified social intelligence: the more our species favored gentle, prosocial temperaments, the more it unlocked uniquely human social cognition like language, culture, and cumulative learning.

Mechanisms of Self-Domestication#

Several mechanisms for human self-domestication have been proposed. They all ask: what (or who) did the selecting, if not a human farmer?

- Group-level selection: Bands with more internal cooperation out-survived others.

- Coalitionary enforcement: As weapons and culture evolved, even physically weaker individuals could form coalitions to punish or expel violent bullies, thus removing those genes from the pool [^21][^22]. Indeed, anthropologist Richard Wrangham suggests that once early humans had language, subordinates could conspire to execute over-aggressive alpha males, enforcing a new social order [^23][^24].

- Female-centered selection: An equally intriguing set of hypotheses puts females at the center of self-domestication.

- Female mate choice: It has been suggested that women preferentially mating with less aggressive, more caring men could have gradually bred aggression out of our lineage [^25][^26]. By favoring males likelier to help with children rather than fight, females would boost the fitness of gentle traits [^27][^28].

- Female coalitions: Additionally, comparisons with bonobos (a self-domesticated ape relative) hint that female coalitions can directly curb male aggression [^29][^30].

Before evaluating these female-driven forces in detail, let us clarify why females had such a pivotal evolutionary role in the first place.

Why Evolution Pressured Females Differently#

In most mammals – and certainly in hominins – the biological roles of females and males in reproduction and survival have key differences. Female humans gestate, give birth to, and nurse offspring; they also typically shoulder the bulk of early child-rearing.

Males, in contrast, have historically invested more in mate competition (and in humans, activities like hunting or territorial defense) and can theoretically father many more offspring with less direct caregiving. These differences mean that the “criteria for success” were not identical for the sexes: a female’s reproductive success depended on her ability to keep a vulnerable infant alive to adulthood, whereas a male’s success might depend more on access to mates and status.

Thus, selection on social traits – like empathy, patience, aggression, cooperation – would act in somewhat divergent ways on women vs. men.

The Maternal Crucible: Intense Cognitive Demands#

For early human females, motherhood imposed intense cognitive and emotional demands. Human infants are extraordinarily helpless, born immature and requiring years of constant care. A mother who could better interpret her baby’s needs – who could soothe, nurture, and teach effectively – had a huge advantage in passing on her genes.

Traits like emotional attunement, compassion, and the ability to anticipate an infant’s mental state (hunger? fear? curiosity?) would directly improve offspring survival. Over many generations, such pressures would select for greater theory of mind and empathy in mothers.

Notably, human mothers do demonstrate striking mental adaptations: for instance, neuroimaging shows that motherhood heightens a woman’s ability to recognize emotions and intentions from infant cues [^31][^32]. Even at a behavioral level, studies find that girls and women excel in social cognition tasks from childhood onward – for example, by age 6–8 girls significantly outperform boys in understanding others’ beliefs and feelings [^33][^34].

This suggests that evolution (not just culture) produced sex differences in social aptitude, consistent with females historically bearing greater social-cognitive demands. In short, when social intelligence became vital, females had to level up first – their reproductive success was on the line with every cry of a newborn.

Male Evolutionary Trade-offs: Competition vs. Cooperation#

Meanwhile, males faced a different set of pressures. In ancestral environments, male fitness was often enhanced by competitive and risk-taking behaviors – fighting for dominance, hunting large game, etc. Aggressiveness and physical prowess could yield mating opportunities or resource control.

These traits don’t reward subtle social intelligence in the same immediate way that nurturing does (in fact, too much empathy might be a liability in violent competition). Thus, male evolution likely involved a trade-off: some selection for social skills (males also needed to cooperate to hunt or form coalitions), but also counter-selection preserving aggression and size for contests.

The result is that even today, human males have higher testosterone and are more prone to physical aggression, on average, than females – a remnant of past selection – whereas females score higher on empathy and emotion recognition [^35][^36]. As one scientific study succinctly reported, “females were faster and more accurate than males in recognizing dynamic emotions.” [^37]. This aligns with the idea that women evolved to be the more socially perceptive sex, out of necessity.

Leading the Way, Not Excluding Men#

It’s important to emphasize that evolutionary “earlier” does not mean men didn’t evolve these traits at all. Rather, it means women may have led the way. Any genes or behaviors conferring better social intelligence in mothers would eventually spread to all humans (males inherit genes from mothers as well). But initially, those traits are most heavily favored in females, since that’s where the payoff is greatest.

Over time, as group life became more interdependent, males who lacked prosocial skills would also be penalized (a brutish man might be ostracized or executed in a self-domesticated society [^38][^39], or simply less desirable to females). Thus, men “caught up” to some extent in social intelligence, but likely later and more indirectly.

In the grand arc of prehistory, one can imagine that women’s evolutionary adaptations for nurturing and cooperation set the stage upon which both sexes then fully embraced the hyper-social human lifestyle.

Female-Led Foundations of Human Social Life#

With the above context, we can identify several female-centered evolutionary forces that would have driven the enhancement of social intelligence and prosocial temperament – effectively making women the architects of our self-domestication. These forces operated through the critical roles that females played in early human groups: mother, alloparent, mate selector, and social networker. We examine each in turn.

1. Mothers and Cooperative Caregiving (“It Takes a Village”)#

Perhaps the most powerful driver of advanced social intelligence was the evolution of cooperative child-rearing in humans. Anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy and colleagues have compellingly argued that our species became a “cooperative breeder” – meaning mothers did not raise children alone, but with help from others (fathers, grandparents, siblings, etc.) [^40][^41].

This was not optional; it was essential for survival. Human infants are so needy, and inter-birth intervals (spacing between children) in our lineage became so short, that a mother without assistance simply could not feed herself and protect her baby at the same time [^42][^43]. In prehistoric savanna environments, a lone mother would likely fail: “there is no way mothers could have kept offspring safe and fed and survived themselves unless they had had a lot of help” [^44]. Thus, shared care (alloparenting) evolved as a vital adaptation, enabling the genus Homo to flourish [^45].

Implications for Infants: Evolving Social Savvy#

This shift to communal child-rearing had profound implications. It meant that infants were raised in rich social environments, exposed to multiple caregivers, not just their biological mother. A baby now had to attract and hold the attention of other adults or juvenile helpers as well, essentially soliciting altruism from anyone willing to babysit or feed it.

According to Hrdy, this created a novel selection pressure on the infants themselves: “babies needed to monitor others, understand their intentions, and appeal to them so as to elicit care” [^46]. In other words, the offspring of cooperative breeders evolved to be socially savvy from the start. Those who were a bit more charming, more attuned to caregivers’ moods, more “adorable” in responding to cues – they survived at higher rates [^47][^48].

Over generations, human babies became other-regarding, born with a drive to engage and ingratiate themselves with anyone who might help [^49]. This is likely the root of our unparalleled social awareness: even toddlers try to share and communicate. Psychologists find that infants in caregiving-rich settings (e.g. with extended family or daycare) develop Theory of Mind earlier than those cared for by only one person [^50][^51]. All this suggests that the cooperative breeding context drove the evolution of mutual understanding and “mind-reading” skills at a very early stage of development.

Implications for Mothers: The Social Radar#

Not only did babies adapt – mothers themselves evolved new capacities in a cooperative breeding system. A mother who must rely on others’ help becomes acutely sensitive to the social environment. She has to trust helpers and also possibly manage relationships to ensure help continues.

Over evolutionary time, human mothers likely became more flexible and discerning, adjusting their commitment to an infant based on available support [^52][^53]. (Tragically, if help was absent, even a loving mother’s unconscious calculus might cause her to reduce investment in an infant she can’t sustain [^54][^55] – a harsh reality in our evolutionary past).

The point is that human mothers developed a finely tuned social radar: they respond to cues of support or threat in their group when deciding how to allocate their immense maternal energy [^56][^57]. This would favor heightened theory of mind (to discern others’ intentions toward her child) and emotional regulation (to maintain alliances and not alienate helpers). A mother who flew into rages or failed to empathize with an alloparent’s needs would lose assistance; thus impulse control and empathy were at a premium for ancestral women.

Furthermore, mothers in a cooperative context had to sometimes communicate their needs or their infant’s needs effectively to others. This could be a catalyst for the evolution of language and pedagogical skills. Indeed, the motivation to share information – like a baby’s health status or a request for help – is naturally strong in caregivers. Humans are unique among apes in their urge to teach and inform others, possibly born from cooperative parenting scenarios [^58][^59].

In short, the daily challenges faced by mothers and their helpers created a rich “training ground” for social cognition. Females who excelled in this – who could co-opt others into a shared child-rearing project and maintain a harmonious nursery – would raise more offspring to adulthood. Through this lens, one can see why women as mothers were pioneers of human social evolution: their role forced them to push the boundaries of what primate social minds could do.

2. Grandmothers and the Extended Female Network#

Beyond mothers, other females – especially grandmothers – also played a key role in human evolution. Humans are unusual in that women live long past reproductive age (menopause), which suggests that post-menopausal women were historically valuable to the group (otherwise, evolution wouldn’t maintain their longevity). The leading explanation is the “grandmother hypothesis”: ancestral grandmothers boosted their genetic fitness by helping raise their grandchildren, thereby allowing their daughters to have children more rapidly [^60]. This grandmother effect would increase the overall number of surviving descendants.

Critically, to be an effective helper, a grandmother must deploy significant knowledge, patience, and social skill. She might forage for extra food, share decades of wisdom about seasons or plant uses, or mediate family conflicts. Evidence indicates that the presence of grandmothers is correlated with better survival of grandchildren in traditional societies [^61].

This implies natural selection favored those lineages in which older females remained healthy and cognitively sharp – effectively selecting for resistance to age-related cognitive decline so that grandmothers could continue contributing [^62]. In other words, human evolution likely extended female social intelligence across a longer lifespan, benefiting the whole group.

The Female Social Fabric: Cooperation and Harmony#

Grandmothers (and aunts and older sisters) formed the core of an extended female support network. Before modern times, a typical human band would have multiple related adult women (e.g. a 45-year-old grandmother, her 25-year-old daughter, and teenage granddaughters, etc.). These women would jointly care for kids, share food, and maintain the home base while men were away hunting.

The cohesion and stability of this female network would directly impact group success. Thus, there was high pressure on females to get along, coordinate, and prevent interpersonal ruptures. Traits like consoling others, fairness in sharing, and conflict resolution would be invaluable in this context. If two women fell into dispute, the fallout could jeopardize the entire cooperative childcare system.

Accordingly, females likely evolved stronger impulse control and social savvy to navigate intra-group tensions. Anthropological observations of foraging societies often note that women use informal conflict-resolution strategies (like gossip or elder intervention) to maintain group harmony, rather than resorting to violence. This aligns with the idea that female-driven selection penalized disruptive aggression and rewarded social emotional regulation – a key aspect of self-domestication.

Cultural Transmission via Elder Females#

The grandmother hypothesis also underscores female influence on cultural transmission. Grandmothers often serve as teachers of skills and traditions to the young. They are repositories of knowledge and act as social glue across generations.

This means the evolution of prolonged learning in childhood (a hallmark of humans) and the accumulation of culture over generations likely owes much to the presence of wise, socially engaged elder females. In sum, the human pattern of multi-generational female cooperation created a breeding ground for advanced social cognition and prosocial norms. It is hard to imagine humans becoming the ultra-social learners we are without the scaffold of mothers and grandmothers actively shaping social behavior in each new generation.

3. Female Coalitions and the Taming of Male Aggression#

Another powerful way women spearheaded human self-domestication is through their influence on male behavior – specifically by curbing male aggression.

Mate Choice: Selecting for Gentler Males#

One mechanism is female mate choice. If females consistently prefer to mate with gentler, more provisioning men, those men have higher reproductive success, spreading “friendly” genes. There is evidence that, in humans, female choice has indeed contributed to reducing sexual dimorphism (males becoming relatively smaller) over the long term [^63][^64].

The logic is straightforward: a less aggressive male is more likely to help with offspring and less likely to harm his mate; women who chose such males had more surviving children [^65][^66]. Over time, this could “feminize” the male population – which is exactly what we see in the fossil record: male Homo sapiens are much less macho (in skull features, etc.) than male Neanderthals or earlier hominins [^67].

One study proposed that “female choice of less aggressive males as mates… could promote self-domestication, because females benefit by their mates’ greater investment in shared parenting” [^68][^69]. This is essentially women selecting for nice dads over brutal warriors. While male coercion (forced mating by aggressive males) can limit the effectiveness of female choice in some species, humans developed unique social systems that gradually empowered female preference – e.g. community norms against rape, and pair-bonding that gives females some say in partner selection. Thus, sexual selection likely worked in tandem with natural selection to favor prosocial males.

Collective Action: The Bonobo Model and Beyond#

Females also exerted influence collectively. In many primates, females form coalitions to protect themselves and their offspring from violent males. Our gentle cousins the bonobos are famous for this: unrelated female bonobos band together to stop male harassment [^70][^71]. If a male bonobo becomes overly aggressive toward a female, a group of females will unite to chase him off or attack him, effectively enforcing a matriarchal peace.

As a result, bonobo society is far more tolerant and less dominated by male aggression than common chimpanzee society. Researchers observing wild bonobos found that “whenever females formed coalitions, they would invariably attack males… typically in response to a male displaying aggressive behavior towards another female” [^72][^73]. Female bonding nullifies the male’s physical advantage, enabling a cooperative social order. The end result is that bonobo females collectively domesticated their species – bonobos show many domestication syndromes (smaller skulls, playful adult behavior) and an egalitarian social structure [^74][^75].

It is very plausible that early human females did something similar. Once our ancestors had the cognitive wherewithal to form alliances, women could team up to discourage or punish abusive males. Even in patriarchical ape societies like baboons, there are cases where females collectively drive off a dangerous male.

In humans, female coalitions may have been subtler – for example, spreading reputation information (gossip) about violent men, coordinating to refuse a bully’s advances, or appealing to male kin for protection. All of these are fundamentally social intelligence operations: they require communication, theory of mind (e.g. “if we all shun him, he’ll realize he’s excluded”), and emotional unity among the women.

Over time, these female strategies would make it costly for males to be excessively aggressive. Males who cooperated and respected social rules would have mates and community support; those who didn’t could end up ostracized or even executed once broader group cooperation (including other males) evolved. In this way, female-driven dynamics likely put the first brakes on male aggression long before formalized laws or chiefly authority existed.

Shifting Power Dynamics Favoring Cooperation#

It’s telling that human males are much less outright dominant over females than in our primate cousins. In chimpanzees, any adult male outranks any female, and males regularly intimidate females. In human hunter-gatherers, while men often hold more political sway, women have their own spheres of influence and can exercise choice and alliance in ways chimp females cannot.

This suggests that early in human evolution, something shifted – likely through cooperative childcare (which increases female leverage and value in the group) and through females collectively insisting on more egalitarian treatment. We might say women’s alliance-building was an early form of “group regulation” of antisocial behavior, a precursor to the later male-led coalitions that executed tyrants. Both were important, but females had the initial motive (being the targets of male aggression) and perhaps set the precedent that pure brute force would no longer reign supreme.

4. “Recursive Mind-Reading” and Social Training in Female Life#

Being the “evolutionary vanguard” of social intelligence also means that females had greater opportunity to refine those skills across their lives. Consider a typical girl in an ancestral human band: from a young age, she likely babysits siblings, learning to interpret a toddler’s moods and how to calm a crying infant – practical training in empathy and manipulation (in the neutral sense of managing others’ emotional states).

As she grows, she spends a lot of time with other women in food gathering or food preparation. These daily activities are usually highly social: women talk, tell stories, and subtly compete in reputation. There is evidence that language might have been particularly advantageous to women in such contexts for coordinating cooperative tasks and social networking.

By the time a woman becomes a mother, she has a rich social knowledge to draw on, from understanding kin relationships to remembering who helped her when she was in need. All this amounts to a continuous exercise in recursive social reasoning: “I think that she thinks that I should do X so that she will help me in the future.” Such multi-layered perspective taking is the pinnacle of theory of mind, something at which humans excel and computers still struggle. Women, by the demands of their typical roles, would have practiced this more intensely (whereas a man might hone other skills like tracking animals or making weapons, involving more spatial-technical intelligence).

It’s no surprise, then, that even today, women on average show an edge in social cognition and emotional intelligence tests [^76][^77]. They are often more adept at discerning interpersonal subtleties – a capacity honed over eons because it was life-saving for mothers and children.

This does not mean men lack these skills; rather, women as a group had to pioneer them to an extreme degree to meet survival needs, thereby pulling the whole species’ abilities upward. Evolution is a game of increments: if women had even a slight advantage in social cognition initially, that could cascade into a major difference over hundreds of millennia, because those skills improved female reproductive success so dramatically. Males would gradually inherit these improvements and find their own uses for them (in hunting teams, trade, etc.), but the path was blazed by females out of sheer necessity.

Addressing Counterarguments#

Any thesis as bold as “women were human first” warrants scrutiny and careful handling of counterarguments. We address a few potential objections: • “Men also needed social intelligence (for hunting, warfare, male alliances), so why single out women?” – Indeed, male activities in human evolution did involve cooperation: a band of men hunting a large animal must communicate and trust each other; warriors in a skirmish benefit from coordination and reading the enemy. However, the frequency and stakes of these scenarios differ from female-driven ones. A mother interacts with her child and kin daily, honing her social tools constantly, whereas a male hunt or fight is intermittent. Moreover, male coalitions often had the option of enforcing cooperation through hierarchy or force (an alpha could lead, and others followed under threat), which relies less on subtle mind-reading. Female cooperation, in contrast, could not be enforced by violence – it had to be achieved through negotiation, reciprocity, and empathy. Thus, while both sexes contributed to evolving social intelligence, the intensity of selection on fine-grained social skills was greater for females. Over time, males certainly benefited and evolved these traits too (a purely asocial male would be marginalized in any human society), but the initial arms race for better social minds was arguably fostered in the female sphere of childrearing and community nurturing. • “Is this argument saying women are ‘superior’ to men?” – No. It is about different evolutionary pathways, not value judgments. Saying women were the evolutionary vanguard of social intelligence is akin to saying “wings evolved before flight muscles” – one had to come first for the system to work, but both are now part of the whole. Men and women today are obviously both “fully human” in their cognitive abilities. The argument is that because of sexual division of labor and roles, the selection for certain human-defining traits happened earlier or more strongly in females, thereby catalyzing those traits in the species as a whole. It does not mean women today are automatically more socially intelligent than men in every case (individual variation is huge and culture matters). It means that to understand how our ancestors acquired their unique social nature, we must pay attention to female-led selection pressures that traditional “man-the-hunter” narratives have downplayed. • “What about men’s role in domestication via punishing tyrants or forming egalitarian bands?” – Researchers like Wrangham and Boehm have highlighted how male cooperation (even including executing overly aggressive males) was key in human self-domestication [^78][^79]. We acknowledge this as an important mechanism once human groups reached a certain level of organization. However, we note that such “language-based conspiracies” [^80] among males likely became possible after a baseline of social cohesion and trust had evolved – a baseline that female-driven cooperative breeding helped establish. In a proto-human society rife with distrust and aggression, it’s unlikely subordinates (male or female) could team up to kill an alpha; some initial tempering of aggression and increase in prosocial sentiment was needed. Female influences (mate choice, coalitions, shared childrearing) could have gradually mellowed the social environment, enabling stable male-male alliances to form without instantly descending into violence. Thus, we see male and female mechanisms as complementary in self-domestication, with females probably acting as the “first line of selection” against raw aggression (by not mating with it or tolerating it), and males later reinforcing those norms through collective action. Our thesis specifically elevates the often-neglected female contributions at that early stage. • “Isn’t this all just speculation? What hard evidence supports women’s impact?” – Direct fossil evidence of behavior is hard to come by, but we do have consilient support from several angles. The morphological changes in humans (skull feminization, reduced sexual dimorphism) hint that selection was reducing traditionally male-linked traits [^81][^82]. The bonobo comparison provides a living proof-of-concept that female-driven social selection can transform a species’ temperament [^83]. Developmental psychology shows that having multiple caregivers accelerates social cognitive development [^84], supporting the idea that cooperative breeding was a catalyst for human-like cognition. Cross-cultural studies find that in many human societies, women excel at social networking and conflict mediation, roles tied to higher theory of mind. Even neuroscience finds sex-linked differences in empathic processing consistent with females’ long-standing specialization in caregiving and social sensitivity [^85]. While no single piece of evidence “proves” the thesis, the convergence of evolutionary logic, empirical studies, and comparative anthropology all point to the same conclusion: female-centered selection pressures were integral to making humans the ultra-social species we are. • “Why avoid the gathering vs. hunting argument about provisioning?” – Often, discussions of women in human evolution focus on the fact that female gathering likely provided a stable food supply, sometimes contributing more calories than male hunting. While that is true and important economically, it is tangential to the evolution of social intelligence per se. One could imagine a scenario where women provided a lot of food but still acted as solitary foragers with minimal social interaction – that wouldn’t advance social cognition. What mattered more was how females organized childcare and social support, not just food. Therefore, we have sidestepped the simplistic “women contributed more resources” argument, because our focus is on cognitive evolution, not a tally of calories. The evidence suggests women’s contributions went beyond nourishment: they created the social environments in which new cognitive strategies (like empathy, teaching, and cooperation) became the difference between life and death. It is that qualitative social contribution that made them the evolutionary vanguard of humanization.

Conclusion#

Human evolution was not driven by a single hero or a single sex – it was a complex dance of biological and social forces. However, in defending the thesis that “if social intelligence made us human, women were human first,” we have highlighted the often underappreciated reality that female-driven selection pressures were likely decisive in shaping our species’ social brains and cooperative nature.

Through the relentless demands of motherhood and alloparenting, women were pushed to develop greater empathy, self-control, and interpersonal understanding – skills that their male counterparts would only fully adopt later as the entire group’s survival came to depend on them. Women’s selective preferences and coalitions helped tame excessive male aggression, steering our ancestors toward a gentler, more communicative social structure. These female-led dynamics set the stage for the self-domestication of Homo sapiens, enabling the emergence of the profoundly social, culturally complex humans we are today.

Crucially, this narrative is not a modern political reimagining of prehistory, but a hypothesis grounded in evolutionary biology and anthropology. It does not claim females are “better” – only that their roles gave them a head start in the evolutionary race toward the Homo sapiens toolkit of social intelligence.

By examining facts like the domestication syndrome in our bones, the cooperative breeding patterns in our childcare, and the cognitive profiles of men and women, we arrive at a coherent picture: women, as the primary caretakers and social organizers, were the first to pioneer the traits that define humanity. Men certainly contributed and eventually matched these traits – once the environment favored them – but the initiating edge was cut by women.

In a sense, women domesticated humanity, perhaps even including men, by cultivating a world in which empathy and cooperation outcompeted brute force. This perspective enriches our understanding of human evolution by ensuring we don’t overlook half of our ancestors. It reminds us that around ancient campfires, it was often the mothers and grandmothers who quietly innovated the art of living together in peace. And it was those innovations – the bedtime story, the shared lullaby, the unspoken pact between friends – that truly made us human.

Sources: Evidence and claims in this report are supported by research in evolutionary anthropology and psychology, including findings on cooperative breeding and social cognition [^86][^87], the human self-domestication syndrome [^88][^89], female coalitions in bonobos [^90][^91], and sex differences in social cognitive abilities [^92][^93], among others, as cited throughout.

FAQ #

Q 1. Does this mean women are ‘smarter’ or ‘better’ than men? A. No. The hypothesis highlights different evolutionary trajectories and selective pressures based on roles, not inherent superiority. Both sexes are fully human, but females likely led the development of social intelligence due to unique demands.

Q 2. Didn’t men also need social skills for hunting and alliances? A. Yes, but the intensity and nature of selection probably differed. Female roles often required constant, nuanced social skills (empathy, negotiation for childcare), while male cooperation might rely more on intermittent coordination or established hierarchies.

Q 3. Isn’t this just speculation without direct fossil evidence of behavior? A. While direct behavioral evidence is rare, the hypothesis draws on converging evidence from comparative anatomy (skull feminization), primatology (bonobo behavior), developmental psychology (caregiver effects), neuroscience (sex differences in social cognition), and evolutionary logic.

Sources#

- Dunbar, R. I. M. (1992). Neocortex Size as a Constraint on Group Size in Primates. Journal of Human Evolution, 22(6), 469-493. https://etherplan.com/neocortex-size-as-a-constraint-on-group-size-in-primates.pdf

- Harré, M. (2012). Social Network Size Linked to Brain Size. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/social-network-size-linked-brain-size/

- Hunn, E. S. (1981). On the Relative Contribution of Men and Women to Subsistence among Hunter-Gatherers. Journal of Ethnobiology, 1(1), 124-134. https://ethnobiology.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/JoE/1-1/Hunn1981.pdf

- Hughes, V. (2013, October 8). Were the First Artists Mostly Women? National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/131008-women-handprints-oldest-neolithic-cave-art

- Hrdy, S. B. (2009). Meet the Alloparents. Natural History Magazine, 118(3), 24-29. https://www.naturalhistorymag.com/htmlsite/0409/0409_feature.pdf

- Landau, E. (2021). How Much Did Grandmothers Influence Human Evolution? Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-much-did-grandmothers-influence-human-evolution-180976665/

- Walter, M. H., Abele, H., & Plappert, C. F. (2021). The Role of Oxytocin and the Effect of Stress During Childbirth: Neurobiological Basics and Implications for Childbirth Interventions. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 12, 742236. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2021.742236/full

- Greenberg, D. M., Warrier, V., et al. (2023). Sex and Age Differences in Theory of Mind across 57 Countries Using the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(5), e2022385119. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2022385119

- Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., et al. (2000). Biobehavioral Responses to Stress in Females: Tend-and-Befriend, Not Fight-or-Flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411-429. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10941275/

- Radford, T. (2004, December 20). Baby Talk Key to Evolution. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2004/dec/20/evolution.science

- de Waal, F. B. M. (1995). Bonobo Sex and Society. Scientific American, 272(3), 82-88. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/bonobo-sex-and-society-2006-06/

- Elephant-World staff. (2023). The Matriarch: The Backbone of the Herd. Elephant-World.com. https://www.elephant-world.com/the-social-structure-of-elephants/

- McComb, K., Moss, C., Durant, S. M., Baker, L., & Sayialel, S. (2001). Matriarchs as Repositories of Social Knowledge in African Elephants. Science, 292(5516), 491-494. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1057895

- Brent, L. J. N., Franks, D. W., Foster, E. A., Balcomb, K. C., Cant, M. A., & Croft, D. P. (2019). Postreproductive Killer Whale Grandmothers Improve the Survival of Their Grandoffspring. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(27), 13545-13550. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1903844116