TL;DR

- Across cultures, myths usually portray women as inventors or patrons of clothing and weaving (with some regional exceptions).

- The motif appears in Eurasian, Indigenous American, East Asian, African, Oceanic, and Circumpolar corpora.

- Quantitative folklore studies (Berezkin 2009 / 2016; d’Huy 2013; Tehrani 2020) indicate several independent origins plus a few deep Eurasian roots.

- Clothing symbolizes cultural consciousness—humans recognise themselves, separate from beasts or gods, the moment they dress.

- Dense clustering of these tales around Neolithic horizons hints at real memories of textile technology transforming daily life.

Introduction – Clothing as Cultural Boundary#

Whether it is Athena threading the first loom or a Greenlandic woman dressing earth-born infants, weaving stories usually arrive with a bigger message: from now on, we are people. Clothing is the visible membrane between nature and culture, and in myth that membrane is spun by female hands. Below I map the motif’s global spread and highlight what the newest phylogenetic work suggests about its age and pathways.

1 · Eurasian & Near-Eastern Cluster

Pandora and Eve#

Hesiod’s Works & Days twice ties Pandora to textiles: Athena “arrayed her in silvery raiment” and “taught her the work of the loom.” 1 Pandora opens the pithos and releases toil, sickness, and mortality—the price of a world grown complicated.

Genesis pushes the same equation harder. Knowledge enters, innocence dies, and Adam and Eve immediately sew fig leaves to cover “the nakedness” of their animal past. 2

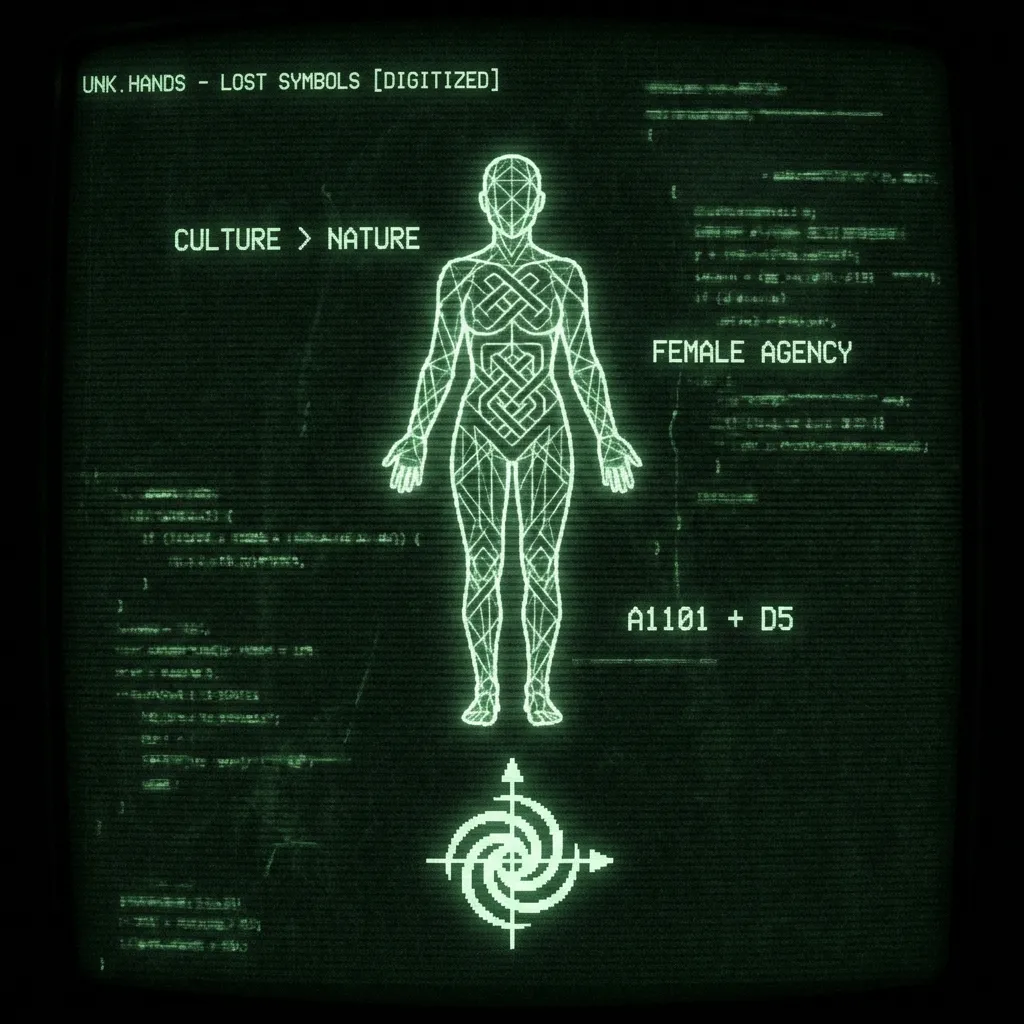

Folklore databases code these as A1101 (“First woman releases evils”) + D5 (“Clothes bestow humanity”), a pairing that later radiates across the Mediterranean and into Islamic and Christian exegesis.

2 · Circumpolar & North America#

In the Greenland Inuit cosmogony earth-babies tumble from the sky; a lone woman “stitched tiny skin garments for them, and they became folk.” 3 Chukchi and Yupik variations keep the same textile pivot.

Berezkin’s network analysis clusters these stories with Paleo-Siberian palettes of tailored skin clothing—arguably a narrative fossil of Upper-Paleolithic cold adaptation. 4

3 · East Asia

Zhinu the Weaver Girl#

Chinese myth keeps its weaving stakes in the stars: Zhinu (織女, “Weaver Maiden”) spins celestial silk across the Milky Way and gifts weaving to humankind. Her annual reunion with the Cowherd is literally measured by 7th-month textile festivals. 5

Some sinologists link the legend to Yangshao-Neolithic loom fragments (c. 5000 BCE), though the textual record is first millennium BCE. Zhinu, not Xi Wangmu, is the clarion civilizer here.

4 · Sub-Saharan Africa#

Dogon cosmology puts sacred cloth at the centre of cosmic order, yet weaving is male labour; a better female textile bearer occurs among the Akan, where Aso—wife of trickster Ananse—teaches kente weaving. 6 In the Mossi origin cycle, goddess Nyido gifts cotton and spinning whorls.

Whether these stories diffused south with Neolithic crops or arose locally is open: gene-flow models (Simões 2023) show Near-Eastern ancestry pulses in Neolithic Maghreb, but the textile myths appear patchy and independent farther south. 7

5 · Andean & Amazonian Fringe#

South America is not blank. In Inca legend Mama Ocllo emerges from Lake Titicaca with Manco Cápac and instructs humanity in weaving and agriculture before founding Cuzco. 8 Still, explicit woman-gives-clothes = civilization stories are rare outside the Andean highlands, implying a local reinvention rather than an ancient pan-American inheritance.

6 · Oceania#

Polynesian Hina figures (Hina-‘ei-te-toga, etc.) beat bark into tapa and distribute it as social currency. Lapita pottery carries textile‐impressed motifs dated ~3100 BP, an archaeological anchor for the myth. 9

Austronesian comparative work by Jordan et al. (2011) shows a strong coast-to-coast spread of textile myths consistent with the well-charted Lapita migration wave.

7 · Phylogenetic Signals#

Berezkin’s motif graphs separate clothing myths into at least three macro-clades:

| Clade | Geographic core | Key motifs | Probable horizon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circumpolar | Siberia–Arctic | D5 + A1335 | Upper Paleolithic |

| Mediterranean | Levant–Aegean | A1101 + D5 | Late Neolithic / Bronze Age |

| Austronesian | SE Asia → Pacific | Tapa-gift motif | Lapita (ca. 1500 BCE) |

d’Huy’s Bayesian runs and Tehrani’s Louvain partitions concur: recurrent invention is real, but some threads are unmistakably ancient.

FAQ#

Q1. Isn’t weaving in many cultures actually a male craft?

In several (Dogon, parts of Polynesia) yes—yet the mythic donor is still female, underscoring symbolic, not economic, assignment.

Q2. Do genetics really track myths?

They can hint at migration routes. Where a myth cluster overlays a known demographic pulse (e.g., Lapita), correlation strengthens the diffusion case.

Q3. Why so few South-American examples?

Andean states preserve one strong exemplar (Mama Ocllo). Elsewhere, textile myths tend to spotlight agriculture or male tricksters rather than a female civilizer, suggesting independent local traditions.

Sources#

Hesiod, Works and Days 62–105 (Loeb ed.). ↩︎

Genesis 3:7, 3:21 (NIV). ↩︎

Knud Rasmussen, Eskimo Folk-Tales (1921), 8–9. ↩︎

Yuri Berezkin, “Peopling of the New World in Light of Folklore Motifs,” in Maths Meets Myths (2016) 71-89. ↩︎

Anne Birrell, Chinese Mythology: An Introduction (1993), 179-183. ↩︎

R. S. Rattray, Akan-Ashanti Folk-Tales (1930), tale 18. ↩︎

Simões et al., “Northwest African Neolithic initiated by migrants from Iberia and Levant,” Nature 618 (2023): 550-556. ↩︎

Garcilaso de la Vega, Royal Commentaries of the Incas, Bk. I ch. 9 (1609). ↩︎

Patrick Kirch, On the Road of the Winds (2017), 120-127; Martha Beckwith, Hawaiian Mythology (1940), 27-30. ↩︎