TL;DR

- Human self-awareness as a recent innovation: The Snake Cult of Consciousness hypothesis suggests our sense of self did not develop gradually over hundreds of millennia, but rather emerged suddenly in the late Ice Age through a specific psychedelic ritual.1

- Snake venom as the first entheogen: Andrew Cutler proposes that snake venom was humanity’s original mind-altering substance. In this view, a prehistoric person’s venom-induced hallucinations led to the very first recognition of the inner self (“I am”), kick-starting conscious self-awareness [^oai1] 2.

- Mythology preserving history: The theory bridges science and Western myth, arguing that ancient stories like the Garden of Eden and serpent-centric creation myths encode a real prehistoric event—the “forbidden” attainment of knowledge (self-consciousness) via snake venom 3 4.

- Alchemy and esoteric synthesis: By uniting empirical research (evolutionary biology, neuroscience, archaeology) with esoteric symbolism (serpents as symbols of knowledge, immortality, and rebirth), the Snake Cult theory creates a modern alchemical narrative. It echoes the age-old Hermetic quest for truth (“know thyself”)—with snake venom acting as a literal elixir of consciousness.

- Puzzles addressed: This synthesis offers possible solutions to the Sapient Paradox (why culture blossomed so late), the ubiquity of serpent symbolism in religion, and even puzzling human traits (e.g. our susceptibility to hallucination). It posits that consciousness was a cultural invention, diffused across the world like a sacred tradition, rather than a slow purely genetic evolution 5 6.

Rethinking Consciousness: Science Meets Myth#

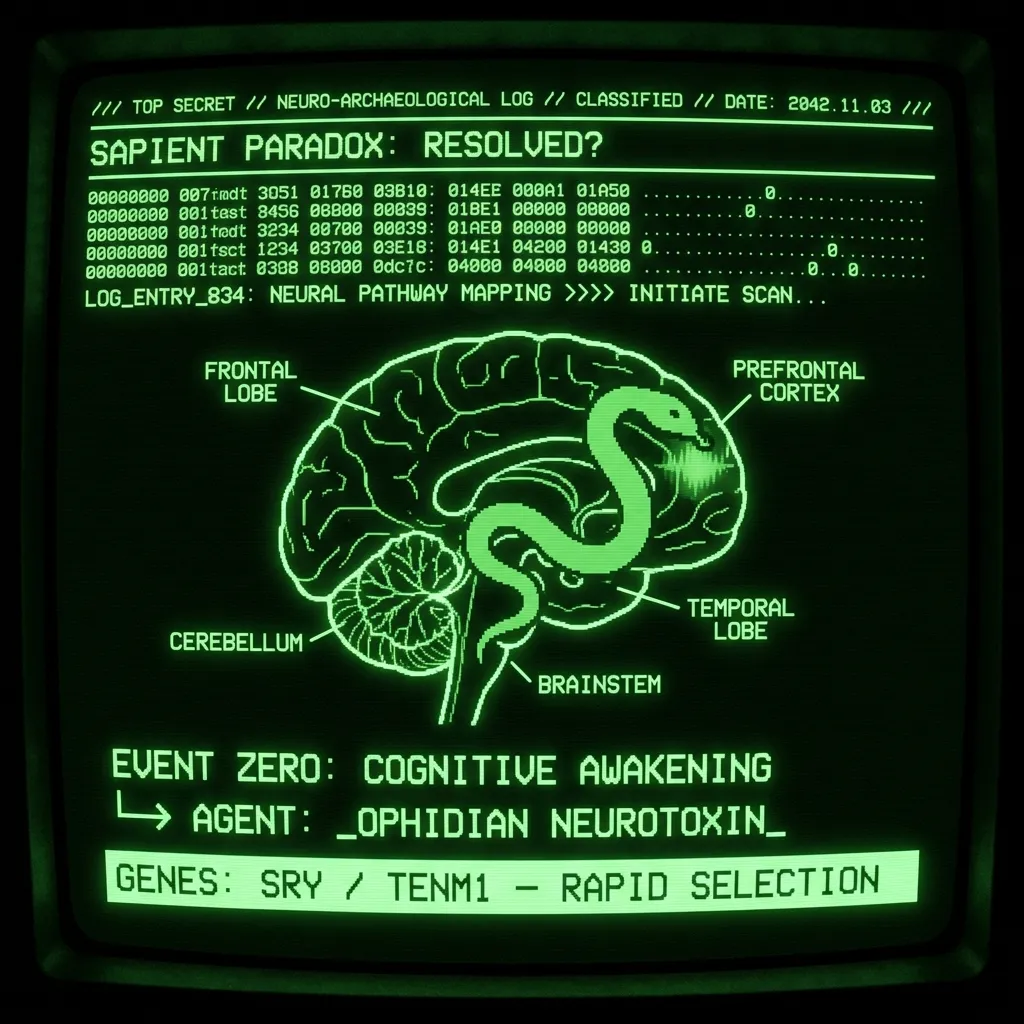

Modern science still grapples with the mystery of how and when humans became self-aware. Fossil skulls and stone tools don’t directly reveal when the light of consciousness “switched on.” Yet many archaeologists and anthropologists suspect that cognitive modernity—the full suite of symbolic thought, language, and self-reflection—arose surprisingly late in our prehistory 7 8. This puzzle is encapsulated in the Sapient Paradox, which asks why anatomically modern humans existed for tens of thousands of years before showing evidence of art, religion, or complex culture 9 8. In other words, if our brains were ready, what triggered the transformative leap to true consciousness?

Cutler’s Snake Cult of Consciousness offers a bold answer: that the trigger was not a slow evolutionary tweak, but a singular cultural event. He argues that around 15,000–12,000 BCE, humans discovered self-awareness through a powerful ritual—a kind of Stone Age initiation involving snake venom as a psychedelic10. The core idea is that a potent neurochemical experience abruptly revealed the self to the human mind. While this sounds unconventional, it builds on an existing thread in evolutionary science. Cognitive neuroscientist Tom Froese, for example, has hypothesized that ritual mind-alteration (intense ordeals, isolation, psychedelics) in prehistoric rites of passage could have catalyzed the development of subject–object separation—the realization that one’s mind is distinct from the world 11 12. Cutler’s twist is to pin this mind-altering agent on snake venom, merging hard science with ancient myth.

The Sapient Paradox and a Radical Catalyst#

Researchers have long noted a disconnect between the emergence of Homo sapiens (anatomically by ~300,000 years ago) and the much later blossoming of behavior like art, religion, and structured language (~50,000 to 15,000 years ago) 9 13. This gap implies that although our brains were biologically modern, something kept early humans from thinking and behaving like “us.” One mainstream explanation is that the capacity for abstract thought and true language may have lain dormant until environmental or social changes drew it out 14. But that raises the question: what could flip the switch on a dormant mind?

Cutler proposes a concrete catalyst: a psychedelic awakening. In his model, an individual (quite plausibly a woman, hence the “Eve” in his theory15) undergoing a snakebite venom trance would experience a harrowing near-death hallucination, including perhaps an out-of-body perspective. Such an event could force a sudden internal reflection—seeing oneself from the outside—yielding the first recognition of the ego or soul 16 17. In effect, the mind met itself for the first time. The hypothesis suggests that this initiatory experience was so profound that it seeded a new meme: the concept of the inner self, which then spread memetically through ritual and story. Crucially, this idea implies that conscious self-awareness is not merely a slow biological evolution, but a cultural innovation that could diffuse across populations like fire.

Modern genetics provides some intriguing support for a late, rapid change. Studies have identified certain brain-related genes under strong selection in the past ~10–20 thousand years – well after humans had spread worldwide 18. For instance, the gene TENM1 (linked to neuroplasticity and learning) shows one of the strongest signals of recent selection in our species 19 18. Such findings hint that our cognitive wiring continued to adapt in the post-Ice Age period, potentially due to new pressures or behaviors. Cutler speculates that once some humans attained sustained self-awareness, there would be evolutionary pressure favoring those who could maintain that introspective, moralizing “inner voice” without external triggers 20 21. Over generations, what began as a rare mystical insight could become an inherited baseline—consciousness as the new normal. This scenario marries cultural anthropology with natural selection in a way reminiscent of an alchemical reaction: an external “potion” (venom) sparks an inner transformation that eventually rewrites our very biology.

Venom, Vision, and the First Mystery Cult#

The choice of snake venom as the primordial trigger emerges from a fascinating mix of practicality and symbolism. In a Paleolithic world, venomous snakes were a ubiquitous danger—and unlike rare psychoactive plants or mushrooms, snakes actively seek us out 22. Early humans, especially in the tropics and subtropics, could not avoid encounters with serpents. It’s easy to imagine that, in fear and curiosity, our ancestors would observe snakebites and their effects. A non-lethal dose of certain venoms can induce dizziness, altered perception, and intense physiological reactions; indeed, rare case reports in modern medicine document visual hallucinations after snakebite (e.g. a Russell’s viper bite causing vivid hallucinations in a patient without other neurological injury)23. Ancient people might well have noticed that venom “intoxication” produces strange mental effects.

Cutler theorizes that at some point a community ritualized this dangerous experience. By experimenting with controlled envenomation – perhaps using smaller snakes, shallow bites, or plant-based antidotes – they found a way to send initiates into an altered state without killing them 24 25. (Notably, folklore suggests certain fruits like apples contain compounds that can mitigate venom’s effects, a possible origin of the snake-and-apple pairing in myth 26 27.) In that altered state, an initiate might undergo a profound ego-dissolution or near-death experience: the sensation of the soul leaving the body or a life review “flashing before their eyes.” Such experiences are well-known triggers for metacognition and spiritual insight in many shamanic cultures 16 28. As one venom mystic (contemporary yogi Sadhguru) described from personal practice, “Venom has a significant impact on one’s perception… It brings a separation between you and your body” 29. In evolutionary terms, a person in this state might, for the first time, perceive their mind as detached from their physical self – essentially discovering the objective “I”.

If one woman or man achieved this breakthrough and returned to tell the tale, it’s easy to see how they could be regarded with awe. That individual could “not unsee” the insight and would carry themselves with a new sense of inner life 30 31. They might also become the first teacher of consciousness – instructing others in the ritual so that they too could “meet their soul.” Thus a cultic practice could form, spreading among bands of humans as a secret rite of passage. The hypothesis aligns with the idea of a prehistoric mystery cult: an initiation in which the participant symbolically “dies” and is reborn with divine knowledge. Over time, safer entheogens like psychedelic plants or mushrooms may have replaced venom in these ceremonies, even as the symbolism of the serpent remained central 32 33. This would explain why serpents and not mushrooms ended up ubiquitous in myths – a point Cutler underscores by noting that, across the world, “snakes are omnipresent in creation myths… Imagine if, everywhere, mushrooms were said to be the progenitors of the human condition… (they’re not)” 34 35.

In summary, the Snake Cult of Consciousness posits a scenario in which human self-awareness was deliberately awakened through a proto-religious ritual. The key claims can be broken down as follows:

- There was a time when humans were not self-aware – they lived and communicated socially but lacked the introspective “I” in the mind 36.

- The discovery of the self was essentially an invention – an insight attained during an altered state (likely via snake venom) that allowed a person to suddenly turn their awareness inward and perceive their own mind as an object 3 37.

- This insight became the core of a ritual tradition – early shamans or initiates packaged the venom-induced vision quest (with antidotes, preparations, and symbolic stories) and spread it memetically across tribes and continents around the end of the Ice Age 38 39.

- The legacy persists in our biology and culture – over generations the practice led to selection for brains capable of sustained self-awareness (obviating the need for the ritual), and the ancient memory of “snakes = enlightenment” endured in myth, art, and religion 40 4.

This audacious hypothesis blends empirical evidence with imaginative reconstruction. It treats myths as vessels carrying real prehistoric memories, which is a hallmark of Cutler’s approach. By looking at science and myth side by side, the Snake Cult theory attempts to answer not just when and how we became conscious, but why so many of our sacred stories return to the image of a serpent offering wisdom.

Serpents and the Alchemical Quest for Knowledge#

One of the most striking aspects of the Snake Cult hypothesis is how it reinterprets widespread Western esoteric symbolism in literal, scientific terms. In Western mythology and mystical tradition, the serpent has always been a paradoxical figure—feared as a tempter or demon by some, yet revered as a font of wisdom and healing by others. Cutler’s theory leans into this paradox, suggesting the snake was both a physical danger and the source of our divine spark. This synthesis casts new light on why serpents occupy such a prominent place in the human imagination, especially in traditions seeking hidden knowledge.

The Serpent as Enlightener in Myth and Mysticism#

In Judeo-Christian lore, the primeval serpent in Eden is the creature that urges Eve to eat from the Tree of Knowledge. Far from being a modern psychedelic metaphor, this ancient story already links a snake, a special plant, and the awakening of discernment (“knowing good and evil”) 41 42. Western esoteric interpretations, such as those found in some Gnostic texts, boldly recast this serpent not as Satan, but as a liberator. Gnostic Christians saw the Eden serpent as an agent of enlightenment, opening Adam and Eve’s eyes and defying a jealous god43. As one scholar notes, within ancient contexts the serpent was “on the contrary” regarded as a source of great wisdom, a symbol of immortality (shedding its skin to be reborn), and the guardian of sacred knowledge 44. In fact, across many cultures the serpent was associated with goddesses of earth and fertility—keepers of life’s secrets—only later demonized by patriarchal retellings 45 46.

Outside of the Bible, serpents abound in Western mythology as bearers of knowledge and power. In Greek lore, the Oracle of Delphi was guarded by a great serpent (Python) until Apollo slew it, and the staff of Asclepius, god of medicine, featured a coiled snake – a symbol that survives on medical emblems to this day 47 48. The hero Herakles (Hercules) battles serpents at pivotal moments, from the multi-headed Hydra to the dragon guarding the golden apples of the Hesperides 49 50. Significantly, those golden apples confer wisdom or eternal life, echoing the Eden motif of a serpent, an apple, and transcendent knowledge. In later Western alchemy and occultism, the serpent Ouroboros—a snake biting its own tail—became a central emblem. This image, found in Graeco-Egyptian texts, symbolizes the unity of all things and the cycle of eternal renewal, “expressing the unity of material and spiritual” realms in endless transformation 51 52. Such symbolism resonates with the idea that a serpent’s power can kill and also confer immortality or enlightenment—the dual nature of forbidden knowledge.

Cutler’s hypothesis takes these esoteric themes and gives them a startling coherence: what if the reason snakes are worshipped, venerated, and feared as knowledge-givers is because, in our deep cultural memory, snakes literally gave us knowledge? On this view, the Garden of Eden story is not a unique Hebrew parable but part of a much older, ubiquitous mythos stretching back to the late Paleolithic. Comparative mythology strongly supports the unusual ubiquity of serpents in creation and salvation stories. From the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl in Mesoamerica who brings learning and civilization, to the cosmic serpent Níðhöggr in Norse myth, or the Rainbow Serpent of Aboriginal Australian lore, serpents appear at the dawn of culture on nearly every continent 53 54. By contrast, entheogenic mushrooms or other plants rarely figure so prominently. This disparity – snakes everywhere, psychoactive plants only in isolated cases – is exactly what the Snake Cult theory would predict if a single serpent-centric cult lay at the root of global mythic motifs 34 35. In a sense, Cutler is reviving an old idea from 19th-century anthropology: that there was a prehistoric diffusion of serpent worship and secret knowledge. Victorian scholars like Miss A. W. Buckland and G. Elliot Smith once argued that “civilization was never independently acquired… it was spread by sun and serpent worship” across the ancient world 55 56. While much of Victorian diffusionism fell out of favor, modern evidence of Stone Age travel and cultural exchange (and perhaps the very universality of serpent symbolism) hints they weren’t entirely wrong 57 58. Cutler’s narrative gives a specific mechanism for that diffusion: the Snake Cult as the world’s first initiated order, transmitting the fire of consciousness.

Alchemical Synthesis – Seeking the Elixir of the Self#

By blending rigorous science with mystical lore, the Snake Cult of Consciousness can be seen as a modern alchemical tale. Alchemy in the Western tradition was always about dual meanings: on the surface the transmutation of base matter into gold, but on a deeper level the transformation of the self in pursuit of wisdom and immortality. In alchemical symbolism, the serpent often represented this process of transformation. The Ouroboros eating its tail signifies the recycling of matter and spirit, the continuous death and rebirth needed to purify and perfect one’s soul 52. Alchemists spoke of an elixir of life or a philosopher’s stone that could grant ultimate knowledge and even eternal life. These fantastical images were metaphors for inner enlightenment—the true “gold” was self-realization.

Cutler’s hypothesis effectively literalizes the alchemical quest. In his story, the “elixir” that catalyzed humanity’s leap was not a mythical potion concocted in a crucible, but venom and fruit taken in a ritual ceremony59. The “lead” to “gold” transmutation maps onto the human condition: our ancestors took the raw, fear-laden experience of a snakebite (lead) and through ingenuity turned it into the gold of consciousness. The alchemical union of opposites is also present. Venom is a poison, yet in tiny doses it becomes a medicine or sacrament; the serpent is deadly, yet it bestows enlightenment. This mirrors the Hermetic principle solve et coagula (dissolve and recombine): the ego had to be dissolved by toxin-induced chaos and near-death, then reconstituted with a new self-awareness. The very fact that apples (associated with life and healing) might biochemically counter snake venom (associated with death) is an uncanny parallel to alchemical dualities of solvent and antidote 27 60.

Perhaps most importantly, the goal of the Snake Cult ritual – to attain knowledge of who we truly are – is precisely the goal of Western esoteric traditions. In the Hermetic and Gnostic worldview, the greatest sin is ignorance of our own divine spark, and the greatest achievement is gnosis: direct knowledge of one’s true self and the cosmos. “Know thyself,” implored the adepts. Cutler’s theory suggests that the first time this commandment was realized as an experience may have been in a hypnagogic venom dream tens of thousands of years ago. He even muses that Eve (whose name in some traditions means “Life-giver”) truly was “the Mother of All Living” in a spiritual sense: “She and the serpent literally initiated Adam into what we now call living.” 3 In other words, woman and snake gave humanity the gift of conscious life, just as esoteric lore often credits feminine wisdom (Sophia, Shakti, Shekinah) and serpent power (Kundalini, the brazen serpent, etc.) with awakening the soul.

This convergence of narratives is what makes the Snake Cult of Consciousness so compelling. It does not dismiss science in favor of myth, nor elevate myth without evidence. Instead, it treats ancient mythology as data – as clues to an event so profound it survived in story form across cultures. Conversely, it treats scientific findings not as dry facts but as parts of a grand human drama. When archaeology shows that the earliest known temple (Göbekli Tepe, ~9600 BCE) is adorned with dozens of carved snakes and was built just before agriculture began, the theory sees confirmation: a snake-centric cult preceded and perhaps sparked the Neolithic Revolution 61 62. Indeed, the discovery of Göbekli Tepe has led researchers to suggest that religious ritual (notably, worship involving fierce animals and perhaps human skulls) came before organized farming – overturning the old assumption that farming came first and religion second 63 64. This aligns with Cutler’s claim that “religion produced agriculture”, that a psychological transformation enabled early humans to imagine farming and civilization 65. In his framework, only after the mind had ingested the “fruit of knowledge” could humanity take the leap into planning, planting, and building for the future 66.

Ultimately, Andrew Cutler’s Snake Cult of Consciousness is a thought experiment that operates on multiple levels. It’s a scientific hypothesis about neurobiology and cultural evolution. It’s also a re-reading of Western esoteric heritage—seeing the alchemical search for truth not as vain mysticism but as a garbled record of something real in our deep past. By synthesizing these realms, the theory invites us to consider that the divide between science and myth, matter and spirit, is perhaps an illusion born of our times. In a primordial initiation on a hilltop lit by fire, as a serpent’s venom coursed through a shaman’s veins, science (chemistry, neurology) and spirituality (vision, revelation) were one and the same phenomenon. The legacy of that moment may live on in every story of a snake in a sacred garden—and in the very fact that we can tell stories about ourselves at all.

FAQ#

Q1. What is the Snake Cult of Consciousness in simple terms?

A: It’s the idea that human self-awareness might have first arisen from an ancient snake-induced hallucinatory ritual. In this scenario, a person bitten by a venomous serpent experienced a mind-altering vision that led them to recognize their own mind (the “self”), and this revelation was then shared and ritualized among early humans as the first “religion” of consciousness.

Q2. How does snake venom act as a psychedelic or entheogen?

A: Certain snake venoms contain neurotoxins that, in very small doses, can profoundly affect the nervous system—altering perception, inducing hallucinations, or near-death experiences.23 The theory holds that early humans learned to harness sub-lethal envenomation to trigger trance states. In those controlled near-death trances, initiates may have experienced out-of-body sensations or visionary insights, comparable to how modern psychedelics can spark mystical experiences.

Q3. Why are snakes linked to knowledge and consciousness in so many myths?

A: Snakes appear in global creation myths and esoteric symbols as givers of wisdom, immortality, or transformation. Examples include the Eden serpent offering forbidden knowledge, Greek legends of dragons guarding golden apples, and the Ouroboros symbol of endless renewal 47 51. The Snake Cult hypothesis suggests this is no coincidence: those myths preserve a memory that snakes literally “gave” humanity knowledge (through venom-visions) in prehistory. In essence, the serpent’s role in myth—as a sly enlightener or sacred guardian—echoes an actual role it played in our ancestors’ awakening of self-consciousness 3 44.

Q4. Is there any evidence outside mythology to support the Snake Cult theory?

A: While direct proof is challenging for such a deep-time event, several clues fit the theory. Archaeologically, the oldest known temple (Göbekli Tepe, 11,600 years ago) is heavily decorated with snake motifs, suggesting a snake-centric cult around the dawn of civilization 61. Genetic studies indicate that some genes tied to brain development underwent rapid evolution in the last 10-15k years 18, which could align with new cognitive pressures from an emerging self-awareness. And anthropological research by scholars like Tom Froese posits that intense adolescent rites and psychedelics could have been used to “kick-start” the reflective, symbolic human mind 11 12—lending mainstream credence to the idea of a consciousness-changing ritual in our past.

Q5. How is this theory connected to alchemy or Western esoteric traditions?

A: The Snake Cult of Consciousness mirrors the alchemical tradition in which obtaining ultimate knowledge (the “philosopher’s stone”) requires uniting opposites and undergoing transformation. Here, the material venom produces a spiritual awakening, uniting biology with insight. Western esoteric symbols like the Ouroboros serpent (symbolizing the unity of spiritual and material in an eternal cycle) and the Garden of Eden story (a serpent granting moral knowledge) are reinterpreted through a scientific lens 52 42. In short, Cutler’s hypothesis is an alchemical narrative for human origins: the poisonous serpent in our myths is actually the catalyst that elevated our ancestors from a natural state to a conscious, self-knowing state – the very knowledge of who and what we are that mystics and alchemists have long sought.

Footnotes#

Sources#

- Cutler, Andrew. “The Snake Cult of Consciousness.” Vectors of Mind (Substack blog), Jan 16, 2023. (Original essay introducing the hypothesis that snake venom-induced hallucinations sparked self-awareness roughly 15k years ago, interpreting myths like Eden as historical allegory.) 3 5

- Cutler, Andrew. “The Snake Cult of Consciousness – Two Years Later.” Vectors of Mind, Jan 29, 2025. (Follow-up article reviewing evidence for the theory, including parallels in mainstream research, genetic findings, and widespread serpent mythology.) 79 [^oai1]

- Froese, Tom. “The ritualised mind alteration hypothesis of the origins and evolution of the symbolic human mind.” Rock Art Research 32.1 (2015): 90–102. (Academic paper arguing that Paleolithic rites (often involving sensory alteration, pain, or psychedelics) facilitated the development of reflective consciousness and symbolic culture.) 11 12

- Senthilkumaran, S., et al. “Visual Hallucinations After a Russell’s Viper Bite.” Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 32.3 (2021): 351–354. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2021.04.010 (Medical case study documenting a snakebite victim experiencing transient visual hallucinations, illustrating venom’s potent effects on the human nervous system.) 72 73

- Mann, Charles C. “The Birth of Religion.” National Geographic Magazine, June 2011. (Report on the discovery of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey – the world’s oldest temple – which suggests that religious rituals (featuring animal symbols like snakes) predated agriculture and catalyzed civilization.) 64 80

- Dietrich, Oliver. “Why did it have to be snakes?” Tepe Telegrams (DAI Göbekli Tepe Research Project blog), April 23, 2016. (Discussion by a Göbekli Tepe archaeologist on the prevalence of snake imagery at the site, and its possible symbolic or practical meanings in Neolithic ritual contexts.) 61 62

- Charlesworth, James H. The Good and Evil Serpent: How a Universal Symbol Became Christianized. Yale University Press, 2010. (A comprehensive study of serpent symbolism across cultures and its reinterpretation in Judeo-Christian thought. Highlights that ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean societies often saw serpents as wise, divine figures before later theologians cast the Eden serpent as the Devil.) 44 46

- Atmos Magazine (Defebaugh, Willow). “Sliding Scales: The Symbolism of Serpents and Snakes.” Atmos.earth, Oct 22, 2021. (Explores humanity’s scientific and spiritual relationship with snakes, noting themes of wisdom, rebirth, healing, and guardianship associated with serpents in cultures worldwide.) 81 82

- Staniland Wake, C. “On the Origin of Serpent-Worship.” Journal of the Anthropological Institute 2 (1873): 373–383. (One of the earliest anthropological papers examining the global “superstition” of serpent worship, puzzled by the recurring choice of the snake as a sacred symbol and calling attention to its antiquity and universality.) 83 84

- Williams, Jay. “Eden, the Tree of Life, and the Wisdom of the Serpent.” The Bible and Interpretation, May 2018. (Analysis by a religious scholar reinterpreting the Genesis Eden story as a conflict between a patriarchal sky god and an older Mother Goddess tradition. Argues the serpent in Eden was originally a positive symbol of wisdom and immortality – a view that aligns with Gnostic and esoteric interpretations.) 42 44

- Ruck, Carl A.P., and Danny Staples. The World of Classical Myth: Gods, Heroes, and Monsters. Carolina Academic Press, 1994. (Academic text on classical mythology; discusses, among many topics, the role of sacred potions and serpents in Greco-Roman myth. Notably mentions the use of anti-venom draughts and serpent-guarded herbs, providing context for the interplay of snakes and psychoactive substances in myth.) 77 85

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Ouroboros.” Encyclopedia Britannica, Last revised May 24, 2025. (Entry describing the Ouroboros symbol – a snake eating its tail – and its significance in Gnostic and alchemical thought as representing the eternal cycle of destruction and rebirth and the unity of the spiritual and material.) 51 52

The hypothesis builds on the idea that behaviorally modern humans appeared abruptly in the late Paleolithic. For instance, Wynn (2009) noted a near-absence of abstract thought in the archaeological record until ~16,000 years ago, despite anatomically modern humans existing far earlier 7 8. This suggests a late cognitive “phase change,” which the Snake Cult theory attributes to a cultural discovery rather than a mutation 67. ↩︎

Cutler coined the tagline “Giving the Stoned Ape Theory fangs” 68 to contrast his proposal with Terence McKenna’s idea that psychedelic mushrooms drove human cognitive evolution. Instead of mushrooms over millions of years, Cutler envisions snake venom as the mind-altering agent that, in one localized time and place, pulled the “trigger” on self-awareness [^oai1]. It’s a highly unconventional take, but it is presented as a serious thought experiment to explain the otherwise puzzling timeline of human consciousness. ↩︎

In his Eve Theory of Consciousness, Cutler emphasizes that women could have been the first handlers of snakes (as gatherers encountering them) and the first teachers of the self-awareness ritual 69. This riffs on the biblical Eve motif. The Bassari people’s genesis myth from West Africa, for example, features a serpent that tricks the first humans and is punished by God with the power to bite (and humans are granted agriculture) 70 71. Such parallels suggest the Eve and serpent pairing in imparting knowledge is a deep cross-cultural memory, not just a Biblical trope. ↩︎

Hallucinations from snakebite are rare but documented. One case report describes a patient who, on the third day after a Russell’s viper envenomation, began seeing vivid visual hallucinations which resolved without neurological damage 72 73. Ethnographically, there are reports of Indian yogis deliberately ingesting cobra venom in tiny doses to induce meditative trance 29. These examples support the plausibility that venom can alter consciousness, especially in the controlled or ritual contexts proposed by the Snake Cult theory. ↩︎ ↩︎

A Gnostic text known as The Testimony of Truth even identifies the Eden serpent as an embodiment of Christ, suggesting the snake was attempting to free Adam and Eve with true knowledge while the Creator tried to keep them ignorant 74. While not mainstream, this interpretation highlights how, in esoteric thought, the serpent can be seen as a savior rather than a villain 75. Cutler’s perspective is akin to this: the serpent is humanity’s enlightener, giving us the defining knowledge that made us human (knowing good and evil, i.e. having a moral, self-aware consciousness) 42 76. ↩︎

The motif of mixing an antidote or potion to withstand a serpent’s bite is actually present in Indo-European myth. For example, heroes often drink a special brew before battling dragons or snakes 77. Ruck and Staples (1994) note that in classical myth, consuming anti-venom herbs or magical drafts was a recurring theme in tales of overcoming serpents. Such stories might be mythologized references to real practices—e.g. taking a preparatory herbal medicine (perhaps rich in compounds like rutin) to lessen venom’s harm 78. The snake + potion combination in myth bolsters the notion that early societies developed a sophisticated method to use venom spiritually without succumbing to it. ↩︎