TL;DR

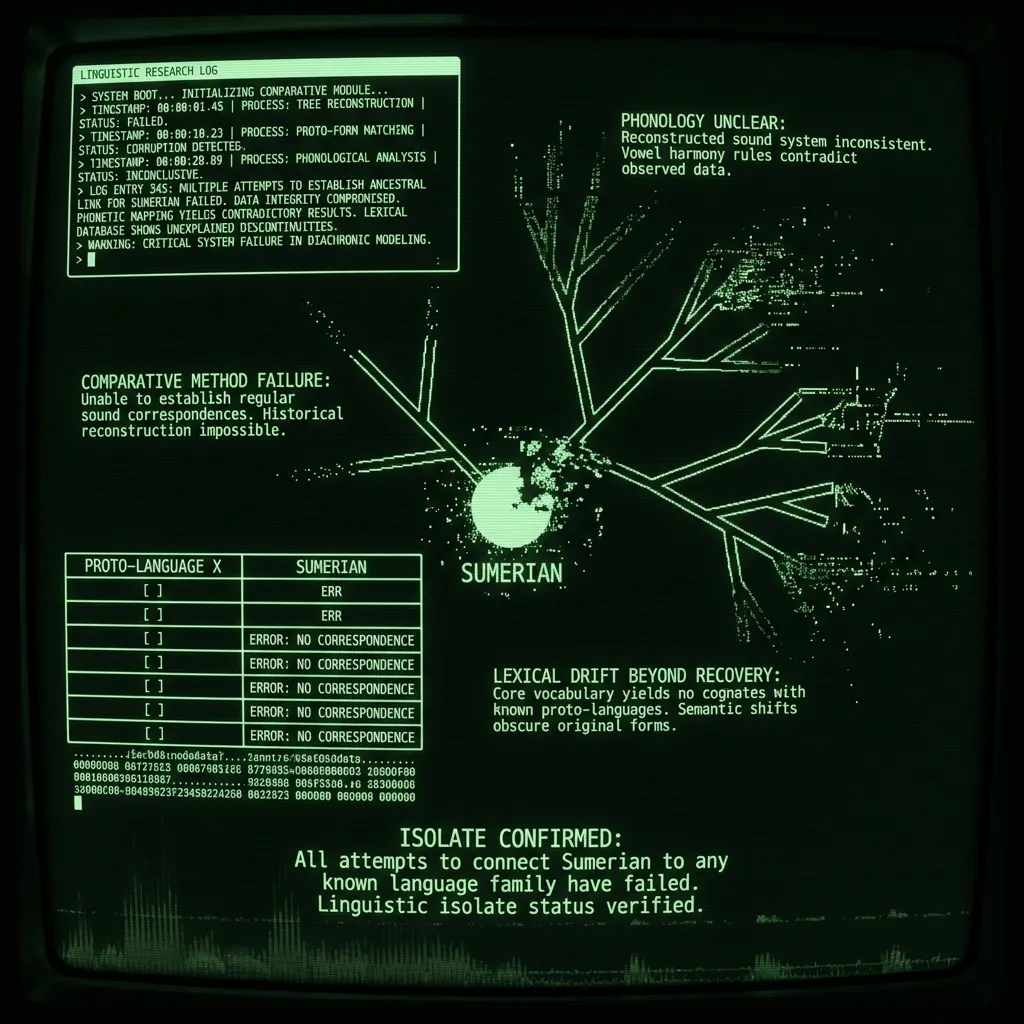

- “Sumerian is an isolate” is a methodological claim: no proposal has produced a defensible set of regular sound correspondences plus shared (especially irregular) morphology meeting comparative standards (Oxford Research Encyclopedia: Sumerian). 1

- Many apparent similarities to other families are typological (agglutination, alignment patterns) and therefore weak evidence for genealogy (Oxford Research Encyclopedia: Sumerian). 1

- The strongest “nearby” explanation for Sumerian’s profile is prolonged contact with Akkadian, including bilingualism and scribal transmission (Cooper, “Sumerian and Akkadian in Sumer and Akkad,” 1973). 2

- The “Proto-Euphratean / pre-Sumerian substratum” hypothesis is best treated as multiple plausible substratal inputs plus major evidential uncertainty, not a clean hidden family; Rubio’s critique is the anchor text (Rubio 1999, JCS 51). 3

- The “Latin analogy” is genuinely apt: after vernacular decline, Sumerian persisted as a scholarly/liturgical code in scribal education and genre traditions, especially in the early 2nd millennium BCE (Michalowski, “Sumerian,” in Woodard; see PDF). 4

“Classification is not a verdict on history; it is a verdict on method.”

— (Paraphrase) comparative-historical practice

What “isolate” means here#

Calling Sumerian an isolate is shorthand for: no genealogical affiliation has been demonstrated using the comparative method (regular correspondences across a substantial basic lexicon + shared morphology with plausible reconstruction). The Oxford reference entry is blunt: Sumerian has “no known relatives.” 1

Two technical caveats matter:

- Unclassified ≠ unrelated. “Isolate” is epistemic: we cannot show its family, not that it had none. The time depth for recoverable signal may be exceeded, or the relatives may be unattested/undeciphered.

- Textuality is a filter. Our “Sumerian” is heavily mediated by scribal norms, orthography, and genre—especially once it becomes a learned language. Michalowski emphasizes the post-Ur III afterlife of Sumerian as an official/scholarly code. 4

The dataset problem: why Sumerian is hard-mode for family classification

Orthography and phonology: correspondence-hunting with a fog machine#

Comparative classification typically needs a reasonably constrained phonological system. For Sumerian, phonological reconstruction is constrained by:

- Cuneiform’s mixed logographic/syllabic practice (and the fact that the script was not designed as a transparent phonemic notation for Sumerian).

- Diachronic stratification and “school norms.” Later copies can preserve older compositions but not necessarily older phonology; and scribal traditions standardize (and sometimes archaize).

This makes it unusually easy to generate illusory lexical matches across language families: if phonological details are uncertain, you can “fit” more candidates than you should.

Typology is cheap: why “agglutinative + ergative” is not a cousin-detector#

Sumerian is often described typologically as ergative and agglutinative (with additional debated features). 1 But typological similarity is not genealogical evidence: these features recur widely and can arise independently or via contact. The comparative method privileges shared innovations and systematic correspondences, not “it kinda looks like X.”

Rule of thumb (boring but real): the more global the typological property, the less probative it is for phylogeny.

Contact with Akkadian: the “closest relationship” is areal, not genetic#

Sumerian and Akkadian coexisted for centuries in a high-contact environment. Cooper’s classic treatment foregrounds bilingualism and the sociolinguistic variables that shape outcomes (elite bilinguals, writing reforms, institutional norms), warning against simplistic stories. 2

Two consequences matter for the classification question:

- Structural convergence: prolonged bilingualism can shift morphosyntax and lexicon, producing similarities that mimic “inheritance.”

- Borrowing with prestige asymmetries: once Sumerian becomes a learned code, lexical borrowing and calquing can be filtered through education rather than ordinary speech communities.

A particularly fruitful modern framing is “language ideologies”: what communities believed Sumerian and Akkadian were for, and how that shaped textual practice in the early 2nd millennium BCE. 5

The Latin analogy: spoken language → learned code#

Your “Latin vs vernacular” model is basically correct, with one twist: the timeline is not a single cliff, but a long slope with regionally and socially stratified bilingualism.

Michalowski summarizes a key transition: after the collapse of Ur III, Sumerian retained official status in the south while Akkadian dialects were prominent elsewhere; the scribal tradition reorganized and canonized materials in ways that shaped what “Sumerian” even is for later periods. 4

Table: A linguist’s timeline of Sumerian “modes of existence”#

| Phase | Rough window | Primary mode | Key inference risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | early–mid 3rd mil. BC | vernacular + administration | low: wide functional load implies living language |

| II | late 3rd mil. BC (Ur III) | intense bureaucratic standard + schooling reforms | medium: written standard may outpace spoken reality |

| III | early 2nd mil. BC (Old Babylonian) | learned language in scribal curriculum; literary canon | high: “Sumerian” is heavily scholasticized |

| IV | later 2nd–1st mil. BC | liturgical/scientific prestige code in Mesopotamia | very high: stability reflects institutions, not speech |

Sources anchoring the transition to scholastic/liturgical use: Michalowski’s overview 4 and the “language ideologies” treatment for the early 2nd millennium. 5

Emesal and “registers”: dialect, sociolect, or genre code?#

Sumerian texts exhibit varieties often labeled eme-gir (main variety) and eme-sal (often glossed “women’s language” or “fine tongue”). A key point for linguists is that eme-sal is not merely a dialect label; it is tightly bound to genres and performance traditions, especially laments and cultic material, with much of the corpus dating late relative to “vernacular Sumerian.” 6

The scholarly upshot:

- Some “variation” is best treated as register/genre conditioning rather than evidence of separate speech communities.

- Register-bound phonological alternations can contaminate naive lexical comparisons (“look, an extra cognate set!”) if not stratified properly.

Emesal’s association with lamentation and cult songs (and its later textual prominence) is well treated in the literature on Emesal compositions. 7

Substratum hypotheses: Proto-Euphratean and the problem of identifying “loanword layers”

The claim#

A long-running idea posits that Sumerian contains a layer of “non-Sumerian” vocabulary—often polysyllabic items, names, and terms for material culture—reflecting a pre-Sumerian population (sometimes packaged as “Proto-Euphratean”).

The critique (Rubio 1999 as the pivot)#

Rubio’s JCS paper is the essential reality check: many proposed substratum items are uncertain in reading/meaning, hard to date, or plausibly explainable by other mechanisms (internal derivation, later borrowing, scribal reshaping). 3 Rubio also stresses a methodological point that linguists should appreciate: substratum identification is a probabilistic inference, not a list-making contest.

A more defensible modern stance#

Instead of “there was the substratum,” a cautious position is:

- Southern Mesopotamia likely hosted multiple languages in early urbanization phases (a normal outcome of trade, migration, and city formation).

- Sumerian’s lexicon may preserve several contact layers, but pinning them to a single coherent “Proto-Euphratean” entity is often unwarranted (Rubio 1999). 3

How to do substratum work without embarrassing yourself#

For linguists: if you want to argue substratum, you need more than “polysyllabic + weird.” Minimally:

- Phonotactic anomalies relative to securely reconstructed Sumerian phonology (hard, but not impossible).

- Semantic clustering in domains typical of substrate loans (flora/fauna, craft terms, local topography).

- Stratigraphy: distribution across text genres and periods that plausibly matches historical contact.

- Areal triangulation: parallel loans into Akkadian or neighboring languages (when available), consistent with a shared donor.

Rubio’s “linguistic landscape” discussion contextualizes substratum talk within broader debates about early Mesopotamian multilingualism and the hazards of overconfident reconstructions. 8

“Sumerian is related to X”: a taxonomy of proposals (and why they keep failing)#

Most genetic proposals fall into a small number of failure modes:

- Typology laundering: rebranding agglutination/alignment as “evidence.”

- Lexical cherry-picking: a curated list of lookalikes with elastic phonology.

- No shared morphology: especially no shared irregularities or paradigmatic quirks.

- Time-depth denial: pushing beyond the horizon where the signal survives without exceptional documentation.

Table: Common proposal classes vs. evidentiary status#

| Proposal class | Usual evidence offered | What’s typically missing | Current scholarly status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sumerian ↔ Dravidian (and similar) | lexical lookalikes; typology | regular correspondences; shared morphology | not accepted in mainstream classification practice 1 |

| Sumerian ↔ Uralic / broader Eurasiatic | large-scale lexical matching | correspondence discipline; controls for chance/borrowing | generally regarded as unproven; some modern advocates remain fringe 1 |

| Sumerian ↔ Caucasian / macrofamilies | typology + selective lexicon | falsifiable reconstruction; robust paradigms | typically unaccepted in Assyriology-facing summaries 1 |

| “Euphratic” / unknown IE substrate | substratum in Sumerian lexicon | secure stratigraphy + methodologically constrained matches | criticized as untenable by methodological scrutiny 9 |

Note the asymmetry: reference works and surveys state “no known relatives,” while advocacy pieces often announce certainty without meeting comparative burdens. 1

The “Sumerian as creole” hypothesis: contact, but make it dramatic#

A minority proposal suggests Sumerian descends from a proto-historical creole, presumably arising in multilingual southern Mesopotamia. Høyrup’s paper is a representative articulation—and also a useful illustration of what counts as suggestive versus demonstrative evidence. 10

Two methodological issues:

- Creole diagnostics are not straightforward, especially when the input languages are unknown and the data are textual/orthographic.

- Morphological complexity cuts against simplistic pidgin→creole narratives (a point raised in critiques and discussions of the hypothesis). 10

For linguists, the value of the creole hypothesis may be less “this is true” than “this forces us to model early Mesopotamia as deeply multilingual,” which aligns with more conservative contact-oriented treatments—without requiring a creole origin story.

What would it take to de-isolate Sumerian?#

A serious path to classification would require at least one of the following:

- A new corpus event: substantial bilingual/trilingual material with a currently unknown language that can be independently interpreted.

- A correspondence breakthrough: a proposed relative that yields a large, regular correspondence system across securely segmented morphemes (not just lexemes), with plausible reconstructions.

- Paradigmatic anchoring: shared irregular morphology (suppletion, fossilized alternations) that is hard to borrow and hard to fake.

Absent that, the epistemically honest position remains: Sumerian is unclassified; the strongest explanatory forces are contact, textual transmission, and possible substrata, not demonstrated genealogy. 1

FAQ #

Q 1. In historical-linguistic terms, why is “Sumerian is an isolate” not a strong metaphysical claim?

A. Because “isolate” only reports that no genetic affiliation has been demonstrated by the comparative method; it does not assert that relatives never existed, only that current evidence (and its textual mediation) doesn’t permit a defensible classification. 1

Q 2. What is the strongest alternative to “hidden relatives” for explaining Sumerian’s similarities to other languages?

A. Long-term contact with Akkadian in a bilingual scribal ecology can generate lexical and structural convergence that mimics inheritance, especially once Sumerian becomes a learned code transmitted through schooling and genre conventions. 2

Q 3. Does the Proto-Euphratean substratum hypothesis de-isolate Sumerian?

A. No: at best it posits one or more earlier donor languages contributing loan layers, but Rubio’s critique shows that identifying and dating such layers is uncertain; even if substrata existed, they don’t automatically yield a reconstructible family relationship. 3

Q 4. Is the “Latin analogy” historically accurate for Sumerian?

A. Broadly yes: after vernacular decline, Sumerian persists as a prestige scholarly/liturgical language within scribal education and textual traditions, producing a form of linguistic stability driven by institutions rather than everyday speech. 4

Footnotes#

Sources#

- Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. “Sumerian.” (accessed 2025-12-18). 1

- Michalowski, Piotr. “Sumerian.” In The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World’s Ancient Languages (overview PDF). 4

- Cooper, Jerrold S. “Sumerian and Akkadian in Sumer and Akkad 1.” Journal of the American Oriental Society (1973). 2

- Cooper, Jerrold S. “Posing the Sumerian Question.” (1991). 11

- Rubio, Gonzalo. “On the Alleged ‘Pre-Sumerian Substratum’.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 51 (1999). 3

- Rubio, Gonzalo. “On the Linguistic Landscape of Early Mesopotamia.” In Ethnicity in Ancient Mesopotamia (conference volume; OA copy). 8

- Brill (chapter PDF). “Sumerian and Akkadian in the Early Second Millennium BCE.” (language ideologies / sociolinguistic framing). 5

- Black, J. A. “Eme-sal Cult Songs and Prayers.” (1991). 7

- Høyrup, Jens. “Sumerian: The Descendant of a Proto-Historical Creole?” (1993). 10

- ResearchGate (critical appraisal of “Euphratic” contact claims). “A ‘New’ Ancient Indo-European Language? On Assumed Linguistic Contacts between Sumerian and Indo-European (‘Euphratic’).” (methodological critique). 9