TL;DR

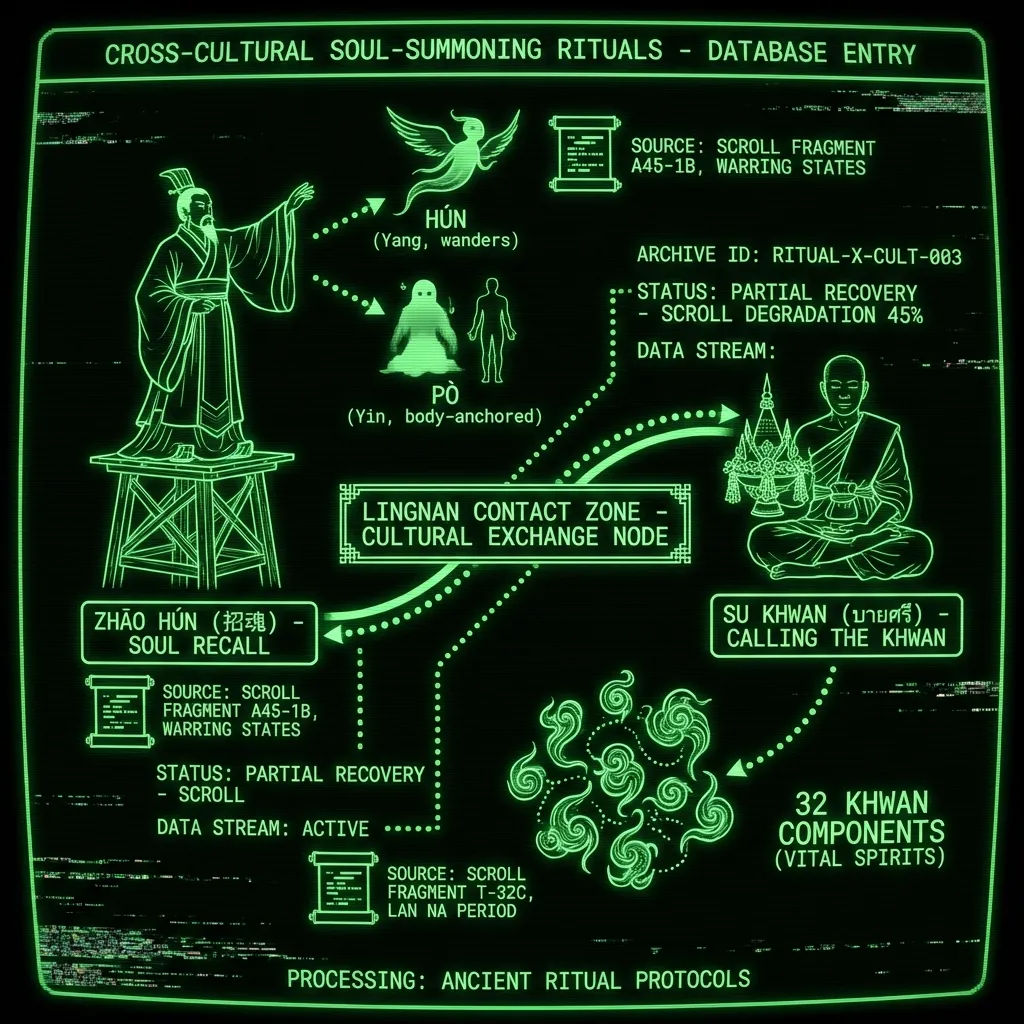

- A single ritual complex in southern China and mainland SE Asia summons a wandering soul back into the body (Chinese 招魂, Tai-Lao su khwan/baci).

- Chinese evidence begins with the 3rd-century BCE Chu poem “Summons of the Soul” and later Daoist medical petitions; folk versions still occur today.

- Tai-Lao su khwan binds the soul with white threads and a paa khwan tray; it marks healing, journeys, weddings, and more.

- Linguists note near-homophones hún/khwan and matching scripts, pointing to early cultural contact in Lingnan.

- The rite endures because it offers psychological first-aid, easy doctrinal plug-ins (Daoist, Buddhist, animist), and a sticky lexical root.

1 Chinese side: 招魂 zhāo hún#

| Layer | What happens | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Warring-States (c 3rd BCE) | Chu-shaman climbs a tower (or rooftops), waves clothes, threatens demons in the four quarters, then bribes the soul with banquets—this is the poem “Summons of the Soul” in Chu ci.([De Gruyter Brill][2]) | If the ethereal hún wanders, the body collapses. Fear, coma, or near-death are “soul-loss.” |

| Medieval Daoism | Priest writes a Petition for the Return of the Hún Souls and Restitution of the Pò Souls; altars, registers of life & death, paper effigies.([MDPI][3]) | Here the goal is medical: erase the patient’s name from the death-register, re-inscribe it in life. |

| Folk practice, rn | Family stands outside the gate or on the roof, calls the name, shakes a jacket, lights incense; some burn a paper ladder so the soul can climb down. | Seen after bad dreams, accidents, or for toddlers scared by fireworks. |

Dual soul theory: hún (yang, breath, can roam) vs pò (yin, body-anchored). Calling back targets hún only; the pò never left. Elite metaphysics aside, folk healers treat them as “one vital spirit that sometimes gets loose.”([MDPI][3])

2 Tai‑Lao side: บายศรี / su khwan / Baci#

Ontology – Each person has 32 khwan (“components of the soul”). Shock, childbirth, a long journey → some khwan wander.

Ritual kit –

- Paa khwan: silver tray, banana‑leaf cone, marigolds, cotton threads.

- Mor khwan (usually an ex‑monk elder) chants Pali‑Lao formulae, inviting devas to escort the khwan home.

- Participants grasp the tray, then tie the white threads on the wrist to “lock” the souls in. Feast follows.([Wikipedia][4])

Use‑cases – Healing after illness, blessing a new house, send‑off/return journeys, weddings, military drafts. It’s basically spiritual Velcro.

3 Are hún and khwan the same word?#

Phonology – OC reconstruction for 魂 is [m.]qʷˤən; Proto-Tai is xwənA. Consonant cluster + rounded vowel lines up neatly. Mair and Holm think early contact in Lingnan (< Han dyn.). Direction of borrowing remains murky: Chinese→Tai fits the sound correspondences, but Tai→Chinese matches the geography of the ritual (it’s southern, not Yellow-River). The jury’s out—but everyone agrees the shared ritual is too specific to be coincidence.([Language Log][1])

4 Why the ritual persists#

- Psychological first-aid – A culturally legible way to interpret trauma (“part of me left”) and to mobilize communal support.

- Political elasticity – Absorbed into Daoism, Buddhism, village spirit cults, and even state funerals (Tang hun-summoning burials). The core script is short and cheap: call, coax, bind.

- Linguistic stickiness – The hún/khwan root anchors a whole semantic field (luck, morale, vital essence), so the word—and the rite—ride across languages.

FAQ#

Q 1. What situations call for zhāo hún or su khwan? A. Illness, shock, childbirth, or long travel are thought to let part of the soul wander; the ceremony recalls it and restores wholeness.

Q 2. Are hún and khwan really the same word? A. Phonological reconstructions (qʷˤən vs. xwənA) match well, and the identical ritual makes borrowing likely, though scholars debate the direction.

Q 3. Is the Tai-Lao rite essentially Buddhist? A. Modern su khwan often includes Pali chants, but its structure predates Buddhism and adapts equally well to Daoist or local animist frames.

Sources#

- Language Log. “Thai ‘khwan’ (‘soul’) and Old Sinitic reconstructions.” 2019. See [1].

- “Summoning the Soul” (Zhao hun) in Chu ci. De Gruyter Brill. See [2].

- Choo, Jessey. “Calling Back the Soul: From Apocryphal Buddhist Sutras to Onmyōdō Rituals.” Religions 14, no. 4 (2023). See [3].

- Wikipedia. “Baci.” See [4].