TL;DR

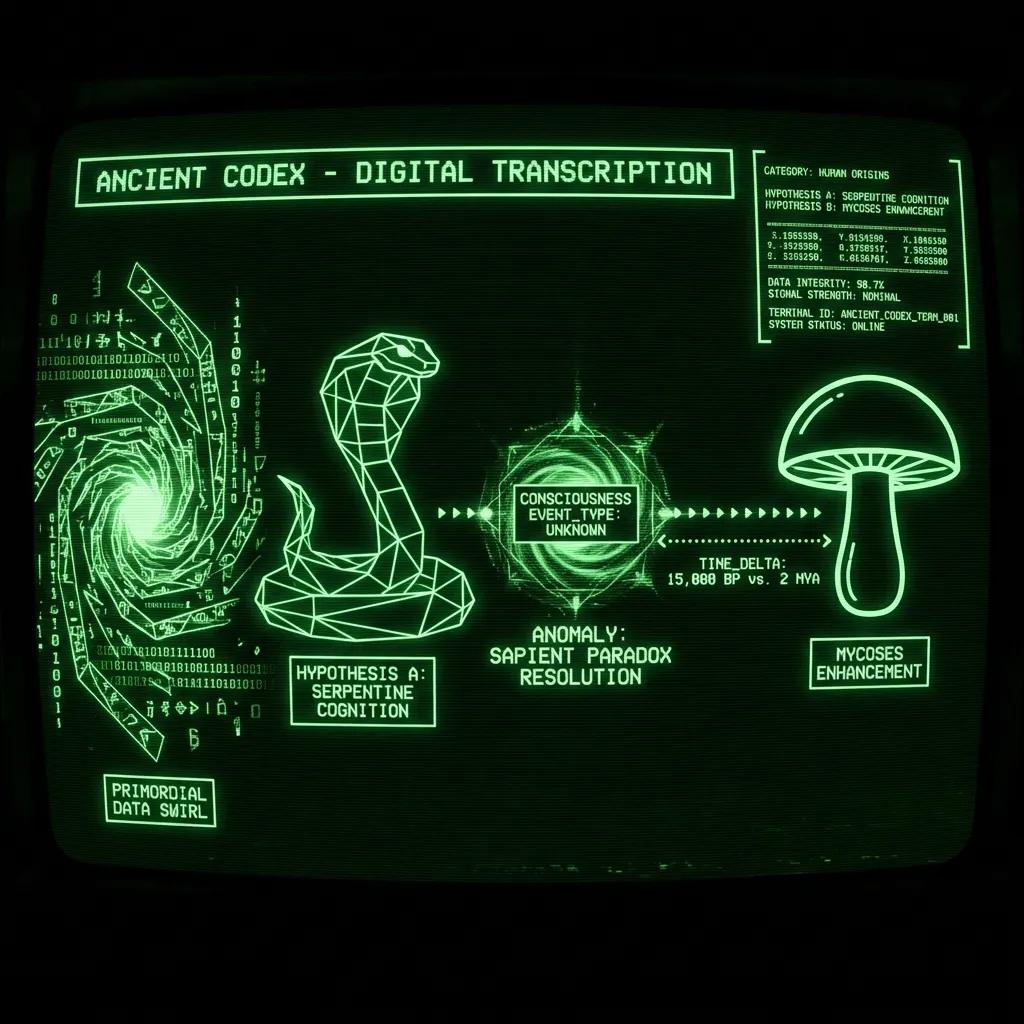

- The Snake Cult/Eve Theory (SC/EToC) suggests snake venom rituals sparked recursive human self-awareness around 15,000 years ago, aligning with the “Sapient Paradox” and widespread serpent mythology.

- McKenna’s Stoned Ape Theory posits earlier cognitive evolution driven by psilocybin mushrooms, but faces challenges regarding timeline consistency and lack of strong archaeological/mythological evidence.

- SC/EToC offers a potentially better fit by integrating comparative mythology, recent genetic findings (Holocene brain evolution), and a gene-culture coevolution model.

Introduction#

Two intriguing hypotheses propose that psychoactive substances catalyzed the evolution of recursive human consciousness – the capacity for self-referential thought (“thinking about thinking”). Terence McKenna’s Stoned Ape Theory posits that early hominins ingested psilocybin mushrooms, which enhanced cognitive faculties (language, imagination, etc.) and spurred a leap in consciousness. In contrast, the Snake Cult of Consciousness (SC) and the related Eve Theory of Consciousness (EToC), recently articulated by Andrew Cutler, suggest that snake venom was the primordial entheogen driving humans to the first realization of the self. In this account, a prehistoric woman (“Eve”) achieved metacognition after envenomation, “discovered ‘I’,” and then taught this recursive self-awareness to others via ritual – founding an ancient snake cult that diffused the knowledge globally. This paper explores these theories across several dimensions – neuropharmacology of snake venom vs. mushrooms, comparative mythology (serpent symbolism vs. mushroom iconography), timeline consistency with genetic and archaeological evidence, and insights from both scholarly research and fringe sources. The goal is to evaluate how each hypothesis accounts for the emergence of modern human cognition and to assess the plausibility of the SC/EToC framework relative to the better-known Stoned Ape Theory.

(Note: Citations are given in Author (Year) format with supporting source links. A full reference list is provided at the end.)

Neuropharmacology of Snake Venom vs. Psilocybin Mushrooms#

Ancient peoples would have readily encountered both snakes and psychoactive fungi in their environment. A key question is whether snake venom could act as a mind-altering substance comparable to psilocybin (the active compound in “magic” mushrooms). Modern medical literature provides primary evidence that snake venom can indeed induce profound neurological and psychological effects. Mehrpour et al. (2018) documented a snakebite victim who, after envenomation, experienced intense visual hallucinations – a phenomenon not widely reported before. In this case, a 19-year-old man bitten by a snake had vivid hallucinations during recovery (suggesting the venom directly altered his perception). Similarly, Senthilkumaran et al. (2021) reported a rare case of a Russell’s viper bite in India leading to visual hallucinations in an otherwise healthy 55-year-old woman. These clinical reports confirm that certain snake venoms can produce psychedelic or dissociative effects on the human mind, albeit as a side-effect of toxic envenomation.

Beyond isolated cases, there is evidence of recreational use of snake venom for its mind-altering “kick.” Jadav et al. (2022) describe snake venom as “an unconventional recreational substance” among Indian psychonauts, noting that some snake charmers in India run clandestine “snake dens” (analogous to opium dens) where patrons seek controlled venom doses for intoxication. In one documented instance, a man struggling with opioid addiction applied cobra venom to his tongue with the help of snake charmers; the venom induced a one-hour blackout followed by “heightened arousal and sense of well-being” that lasted weeks, during which he lost all craving for opioids. Remarkably, the euphoria and anti-addictive effect from a single envenomation exceeded any “high” he’d experienced from conventional drugs. This parallels findings with psychedelics like psilocybin, where one dose can occasion lasting antidepressant or anti-addictive outcomes. Indeed, the patient likened the post-venom state to a transformational “reset,” much as psilocybin therapy patients do. Such reports bolster the plausibility that venom, under controlled dosing, can act as a potent psychoactive agent.

Chemically, snake venoms are complex cocktails of neurotoxins, peptides, and enzymes. While their primary evolutionary purpose is immobilization of prey (or deterring predators), some components interact with neurotransmitter systems in ways that could alter consciousness. For example, cobra venoms contain trace L-tryptophan – an amino acid precursor of serotonin. Tryptophan’s indole ring is structurally similar to the backbone of psilocin/psilocybin (the indole-based alkaloids in mushrooms), hinting at a biochemical kinship between venom and classic psychedelics. Of course, one cannot simply “brew” psilocybin out of snake venom – a lab synthesis from tryptophan requires multiple steps. However, Cutler (2023) speculates that Paleolithic humans might have found ways to detoxify or process venom to accentuate its hallucinogenic properties. While this remains conjectural, it is notable that other indigenous innovations (e.g., preparing ayahuasca from two plants to activate DMT) show a capacity for sophisticated chemical manipulation in antiquity. It’s thus not implausible that early experimenters learned to tweak venom – for instance by mixing it with plant extracts or administering it in sublethal micro-doses – to induce trance states rather than fatal poisoning.

Pharmacologically, certain venom components target receptors also implicated in cognitive function. Many elapid (cobra, kraits) venoms contain α-neurotoxins that bind to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the nervous system. In large doses, this causes paralysis; but in minute doses, modulating the cholinergic system can affect arousal, attention, and even memory. Notably, venom-derived compounds are being investigated in modern medicine for neurological conditions: e.g., cone-snail venom peptides for pain relief, and snake venom inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) for treating Alzheimer’s disease. One pharmacology study went so far as to claim that “snake venom AChE is the best source of drug design for the treatment of Alzheimer’s” (Xie et al., 2018). This suggests venom can potently influence neurotransmitter pathways related not only to muscle control but also to cognition. Intriguingly, one of the most important neurotrophins in the human brain – Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), which supports neural plasticity and learning – has a functional analog in snake venom: Nerve Growth Factor (NGF). Cobra venom is rich in NGF, and researchers have noted that human genes under recent selection (e.g., TENM1, discussed later) are involved in BDNF regulation. This parallel hints that snake venom biochemistry and human neural evolution might have an unexpected point of convergence. Cutler’s Eve Theory explicitly draws this analogy, proposing that exposure to venom’s NGF-like properties could act as a “cognitive antigen” – a challenge to the nervous system that provokes an adaptive, plastic response (much as an antigen spurs an immune response) resulting in greater self-awareness capacity.

Beyond chemistry, near-death experiences (NDEs) induced by envenomation may have played a role in kick-starting introspection. Venom ritual theorists argue that controlled envenomation rituals in antiquity would bring initiates to the brink of death – a “liminal” state where one might experience dissociation of mind from body. Anthropologists note that many traditional puberty rites or shamanic initiations involve ordeals that mimic near-death states (extreme pain, isolation, intoxication, etc.). In such a state, a person might, for the first time, perceive consciousness as an entity separate from the body, essentially encountering the self or soul. Froese (2015) argues that intense mind-alteration rituals could have originally served to induce subject-object separation in young initiates – forcing them to “meet” their own ego as a thing apart from sensory reality. In Cutler’s scenario, the “first person to think ‘I am’” may have done so during a venom-induced near-death trance, seeing her life “flash before her eyes” and in that reflection recognizing an identity persisting independent of her failing body. The dissociative effect of venom noted by practitioners lends credence to this: Sadhguru, a contemporary Indian yogi, has publicly described ingesting snake venom in small doses to deepen meditation, saying “Venom has a significant impact on one’s perception… It brings a separation between you and your body… It is dangerous because it may separate you for good”. Such testimony suggests that even today, some spiritual seekers use venom to pursue transcendence, viewing it as a sacrament that can catalyze out-of-body awareness. In essence, venom might have acted as a dramatic trigger for nascent metacognition – a biochemical “shock” that forced the brain to observe itself from the outside, seeding the concept of an autonomous self or soul.

By comparison, psilocybin mushrooms are a far more benign and well-characterized psychedelic. Psilocybin (in species like Psilocybe cubensis) reliably induces visual hallucinations, ego dissolution, and mystical experiences by agonizing serotonin 5-HT2A receptors. McKenna’s Stoned Ape Theory speculates that as African hominins transitioned to grassland ecosystems (~2 million years ago), they would have encountered dung-growing psilocybe mushrooms (for example, trailing herds of ungulates) and incorporated them into their diet. McKenna (1992) proposed multiple selective advantages: at low doses, psilocybin might sharpen visual acuity (useful for hunting), while at higher doses it could spark hyperconnectivity in the brain, creativity, and even synesthesia (e.g., triggering the birth of language and symbolic thinking). Over time, regular mushroom consumption could have driven neurogenesis or novel neural wiring, essentially “bootstrapping” the hominin brain to higher complexity. It’s a provocative idea, but largely speculative – we have no direct evidence of mushroom use 100,000+ years ago, and the strong effects of psilocybin (visions, etc.) would be ephemeral unless somehow ritualized. Unlike snake venom, mushrooms are palatable and non-lethal, making them more plausible as a widespread consciousness-altering drug in prehistoric communities. However, the Stoned Ape hypothesis struggles to explain why, if psychedelic mushrooms were globally available in deep prehistory, the flowering of art and culture occurred so late. It also leaves little trace: mushrooms are soft and leave no residues or artifacts for archaeologists. Thus, while neuropharmacologically psilocybin is a proven catalyst for altered consciousness (with modern studies showing it can even occasion spiritual-type insights and behavior change), there is scant cultural or fossil evidence that our ancestors actually consumed them in the quantities or contexts McKenna imagines.

In summary, snake venom is an extreme but not implausible candidate for an archaic psychedelic. There is concrete scientific documentation of its hallucinogenic and transformative effects in humans. Additionally, venom use can be habit-forming in a ritual sense – evidenced by subcultures in South Asia today that seek it for “mind expansion”. Psilocybin, on the other hand, is a known mind-expander with likely prehistoric presence but little evidence of Paleolithic use apart from conjecture. Crucially, the SC/EToC theory does not claim venom is a better psychedelic than mushrooms – in fact Cutler admits “snake venom is not a good trip, all things considered… if it served a ritual purpose, it would eventually be replaced by mushrooms or other local psychedelics, even if the symbols did not change”. In other words, early societies that started with venom cults may later have adopted safer entheogens (like plants or fungi) for ritual, while retaining snake symbolism. This leads us to the mythological record – the fingerprints those early practices may have left on human culture.

Comparative Mythology: Serpents Everywhere, Mushrooms Rarely#

One of the strongest arguments for the Snake Cult hypothesis is the pervasive presence of snake/serpent symbolism in ancient religions and creation myths worldwide, contrasted with the near absence of explicit mushroom imagery in the same contexts. If a particular psychoactive agent played a pivotal role in the awakening of human consciousness, we might expect to see its memory preserved in myth – especially if that awakening was diffused culturally. Indeed, Cutler’s Eve Theory suggests that the Eden story of the serpent and forbidden fruit is a mythologized record of the first attainment of self-awareness. This idea gains plausibility when one recognizes that serpents feature as knowledge-givers or creators in dozens of unconnected cultures:

- In the Book of Genesis, a snake tempts Eve to eat the fruit of knowledge, resulting in the “eyes of Adam and Eve being opened” (Genesis 3:6–7) – a clear metaphor for an awakening to self-consciousness and moral knowledge. The outcome (“their eyes were opened”) parallels the notion of gaining inner vision or self-awareness. Notably, Eve (the woman) is the first to partake and understand, consistent with EToC’s proposal that a woman was the first teacher of selfhood.

- In a West African Bassari myth (recorded by Frobenius in 1921), the first man and woman live in an idyllic land until a serpent persuades them to steal fruit from a god’s tree. When the deity finds out, the snake is punished and humans are cast out, given agriculture and mortality. The correspondence to Genesis – a serpent, forbidden fruit, punishment, agriculture – is striking, yet the Bassari had no Biblical influence. This suggests both stories descend from an older prototype or diffused from a common source. Harvard anthropologist Michael Witzel (2012) indeed argues that such myths may trace back to Africa >50,000 years ago, forming a part of a “Pan-Gaean” mythology inherited from early Homo sapiens. He includes the Bassari snake, the Biblical serpent, and the Mesoamerican Quetzalcoatl in this ancient cluster. However, as Witzel himself admits, maintaining specific story details over 100 millennia stretches credulity. A more plausible explanation is later diffusion: the snake-and-fruit creation story may have spread globally during the late Ice Age or early Neolithic, along with other cultural innovations.

- Mesoamerican lore prominently features serpents linked to knowledge and creation. The Aztec/Maya Quetzalcoatl is the “Feathered Serpent” deity credited with creating humans or imparting civilization (in some versions he retrieves bones from the underworld to create humans, in others he gives maize and knowledge). While not an Edenic fruit scenario, the pairing of a serpent with bringing enlightenment (in Quetzalcoatl’s case, often associated with the planet Venus – a light-bringer motif) is notable. Cutler humorously calls him “the Feathered Fungus” in an imagined world of mushroom myths – but in reality Quetzalcoatl is a feathered snake, again underscoring the serpent as culture hero.

- In ancient India, serpents (Nāgas) are pervasive in myth and iconography. The Naga are semi-divine serpents often associated with hidden knowledge, treasure, and immortality. In the Buddhist tradition, after the Buddha attained enlightenment, it is said the Naga king Mucalinda sheltered him with its cobra hood during a storm, symbolically protecting the knowledge. Furthermore, Vedic myths of Soma, the mystical elixir of the gods, sometimes link it with snakes: one Vedic hymn refers to the milk of a serpent and the Soma in the same breath (the idea being the serpent guards the plant that yields Soma). Cutler notes that Indo-European myths about a drink of immortality (Soma or Ambrosia) often feature serpents either as thieves of the potion or as its guardians. This could encode an ancient memory that “snakes = enlightenment potion”. Even today, there are Hindu ascetics in India who deliberately take diluted snake venom as a form of tantric practice – a fact echoed by the popularity of Sadhguru (who claims to have survived fatal snakebites via spiritual power) and by rural snake-worship rituals. The “venom-drinking sadhus” are effectively a living fossil of a snake cult, using the poison in rites to achieve trance states.

- The Rainbow Serpent is a creator deity in Aboriginal Australian lore, known under many local names across Australia. It is typically a giant snake associated with water, rainbows, and creation of life. In some Aboriginal myths, the Rainbow Serpent “gave the people language and songs, and taught them to hunt and cook”, essentially civilizing them. An example is the Mimi and the Rainbow Serpent story from Arnhem Land, where the serpent is a teacher of culture. Again, a snake is the bringer of knowledge and order.

These examples (and there are many more) illustrate a pan-cultural motif: serpents intertwined with knowledge, creation, or transformation. From the caduceus of Hermes (a staff with two intertwining snakes, later a symbol of healing and perhaps originally wisdom) to the Ouroboros (the snake biting its tail, symbolizing self-reflection or eternity), serpents are arguably the most widespread mythological symbol on Earth. The anthropologist Sir James Frazer once noted that nearly every ancient culture had some form of serpent worship or symbolism, often connected to fertility or wisdom. This ubiquity stands in stark contrast to the scarcity of mushrooms in early art and myth. If one imagines an alternate world where mushrooms were as celebrated, one would expect dozens of creation stories crediting a mushroom god or depictions of fungi alongside deities. Cutler invites us to imagine if “Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Fungus, put a soul in the first couple; Indra obtained the Nectar of Immortality by churning the ocean of milk with a staff of shiitake; Mother Mycelia offered Eve the fruit of knowledge”. In reality, we see none of those – they sound absurd precisely because mushrooms have little to no role in known creation myths.

What evidence do we have of psychoactive mushrooms in ancient culture? There are a few intriguing but isolated cases. One often-cited piece of rock art comes from Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria, dating to ~7,000–5,000 BCE: a cave painting appears to show a shamanic figure with mushrooms sprouting from his body or head, possibly representing a ritual use of Psilocybe or Amanita (the interpretation is contested, but it’s popular in entheogen literature). In Mesoamerica, the Maya and Aztecs certainly knew of and used psychedelic mushrooms (teonanácatl, “flesh of the gods”), but their art does not prominently feature mushrooms. Instead, we have indirect evidence like mushroom stones – small carved stone caps on pedestals found in Guatemala (c. 1000 BCE – 500 CE) which are believed to be cult objects related to mushroom ceremonies. These suggest a localized cultic use, but nothing as globally diffused as serpent imagery. In ancient Egypt, some fringe theorists (Berlant, 2000; Mabry, 2000) have attempted to interpret certain symbols (like the Eye of Horus or the crowns of Upper Egypt) as stylized mushrooms, and even claimed that snake symbology in Egypt was a coded reference to mushroom use. For instance, one hypothesis held that Egyptians deified the Amanita muscaria mushroom and used snake iconography as a stand-in because “snakes are symbols of mushrooms and their venom supplies a buzz”. However, Egyptologists have refuted these interpretations as overreach and misreading of hieroglyphs (Nemo, 2022). The consensus is that no clear depiction of a psychoactive mushroom exists in Egyptian or Mesopotamian art, nor in Greek or Chinese antiquity. In contrast, snakes abound: e.g., the Greek myth of Asclepius (god of healing) involves snakes (the staff with a snake, still a medical emblem); Medusa’s head is wreathed in snakes (and interestingly, her blood both killed and cured, which might encode knowledge of venoms as both poison and medicine – the word pharmakon in Greek means both).

The dominance of snake symbolism in early spiritual artifacts is also evident archaeologically. At Göbekli Tepe (Turkey, ~9600 BCE), one of the oldest known temple sites, pillars are carved with numerous animals – notably snakes appearing in relief, often descending or surrounding stylized human figures. Some researchers (e.g., Andrew Collins) have noted that the snake is one of the most common motifs there, possibly reflecting its importance in whatever belief system the builders had. If Göbekli Tepe’s “temples” record the transition to organized religion at the end of the Ice Age, the prominence of serpents could indicate a cult of the serpent active at the dawn of civilization. Similarly, in Çatalhöyük (Turkey, 7th millennium BCE) and other Neolithic sites, figurines of the “Mother Goddess” are sometimes flanked by or associated with snakes, implying they had a chthonic or regenerative significance. By the Bronze Age, serpent cults are clearly attested: the Minoan Snake Goddess figurines (Crete, 1600 BCE) show a female deity holding snakes in both hands, likely symbolizing her dominion over life, death, and rebirth. Even in early historic times, Greek writers recorded Egyptian snake cults (the god Nehebkau was a serpent who guarded life force; the Therapeutae sect in Alexandria reportedly used snakes in ritual), and Roman mystics like the cult of Glycon (2nd cent. CE) worshipped a prophetic snake deity.

In light of this, the relative absence of mushrooms in iconography suggests that if psychedelics were used in human prehistory, their influence was either not mythologized widely or was subsumed under other symbols. It is possible that some mushroom cults encoded their sacrament as serpents in art – for example, a theory holds that the Nahua (Aztec) word for mushroom nanácatl was represented in codices by a snake symbol due to a pun (one Aztec glyph for a hallucinogenic mushroom is a stylized, fleshy shape that some interpret as two intertwined snakes). This is speculative, but it aligns with the fringe suggestion that snake iconography might sometimes be an esoteric cipher for an entheogen. For instance, one blogger analyzing Egyptian art noted that a certain royal amulet depicting two rearing cobras was argued by pseudoscientists to represent two mushrooms, but only by “holding it upside down because of a preconceived notion that snakes stand for mushrooms” – an argument dismissed as confirmation bias. In any case, mainstream scholarship finds no pervasive “mushroom cult” in the Paleolithic record, whereas a case can be made for a Paleolithic/Neolithic diffusion of serpent symbolism. As Cutler quips, “from Mexico to China to Australia, snakes are omnipresent in creation myths… Imagine if, everywhere in the world, mushrooms were said to be the progenitors of the human condition… (they’re not)”. This stark difference in mythic salience is a key point in favor of the Snake Cult hypothesis over the Stoned Ape Theory: the earliest religious narratives of humanity seem to “remember” a snake-induced awakening, not a mushroom-induced one.

Moreover, the diffusion pattern of mythic motifs supports a relatively recent, post-Ice Age spread. Rather than requiring a 100,000-year oral tradition surviving independently on each continent (as Witzel’s pan-human myth might), SC/EToC suggests that the concept of self and its attendant myths spread along with migrating cultures in the late Pleistocene/early Holocene. This is consistent with evidence that cultural innovations did travel long distances in prehistoric times. For example, genetic and archaeological evidence shows that agriculture, pottery, and perhaps even certain myths, spread from core areas into new regions via migration and trade. A Nature study in 2020 found that farming was brought to West Africa by migrants from the Near East ~7,000 years ago. It is plausible those migrants also carried their creation stories with them. If one of those stories was of a serpent that bestowed knowledge (the memory of a real archaic event), it could have been adopted and indigenized by many cultures, resulting in the myriad serpent myths we see. This idea of cultural diffusion is more parsimonious than assuming every culture independently came up with snake = knowledge by coincidence or “psychic unity”. And indeed, when we tally peculiar global motifs (e.g., the association of the Pleiades star cluster with either sisters or birds in many mythologies, or the association of the bright star Sirius with a canine figure across the Old and New Worlds), diffusion starts to look like the best explanation. Cutler (2023) lists numerous such parallels and argues that the weight of evidence favors ancient interconnectedness of traditions, likely via long-distance storytelling. The snake in the Garden may thus be a universally recognized story element not because it’s inherent to our psyche, but because our ancestors shared the tale as they spread out. In comparison, McKenna’s mushroom hypothesis has virtually no mythological footprint – there is no ancient “Garden of Fungi” story recurring around the world. The closest might be the Soma of the Vedas (often theorized to be Amanita muscaria or another psychoactive); yet Soma is described as a plant juice, not specifically a mushroom in the hymns, and its cult was limited to Indo-Iranian peoples, not global. The Eleusinian Mysteries of Greece involved a kykeon brew that possibly contained ergot or mushrooms, but again this was a localized secret tradition without global analogues. Thus, comparative mythology strongly favors the snake-venom scenario as having left an indelible mark on human cultural memory.

Timeline Consistency: Evolutionary and Archaeological Alignment#

A critical test for any theory of consciousness evolution is how well it fits the known timeline of human biological and cultural development. Modern humans (Homo sapiens) emerged anatomically by around 300,000 years ago, yet the archaeological record shows a puzzling lag before “behavioral modernity” (symbolic thought, art, religion, complex tools) became widespread. This gap – tens of thousands of years – is known as the Sapient Paradox (Renfrew, 2007). In Renfrew’s words, “Why was there such a long gap between the emergence of genetically and anatomically modern humans and the development of complex behaviors?” Early Homo sapiens in Africa (~200–100 kya) had brains as large as ours, but their toolkits and art remained simple for millennia. Only around 50–60 kya (the “Great Leap Forward”) do we see a profusion of symbolic behavior – e.g., ornamentation, cave paintings in Europe, etc. And even then, truly widespread evidence of religion, art, and structured language appears much later, around the end of the last Ice Age (~15–10 kya). As Wynn (2021) observed, “there is no evidence of abstract thought until ~16,000 years ago”. All this suggests that recursive consciousness (sapience) may have been a late acquisition or at least late in fully manifesting. McKenna’s Stoned Ape Theory doesn’t easily account for this timeline – it imagines the groundwork of enhanced cognition being laid perhaps by 100k+ years ago (or even during the early genus Homo, 1-2 million years ago, to explain rapid brain enlargement). If psilocybin drove brain evolution early, one might expect concomitant early cultural expressions of that enhanced mind. Instead, we see a lag of tens of millennia where anatomically modern humans acted non-modern. McKenna’s idea, in essence, pushes the critical changes too far back and leaves the Sapient Paradox unresolved.

The Snake Cult/Eve Theory, conversely, was formulated specifically to solve this paradox by positing a recent, memetic trigger for modern cognition. It decouples anatomical evolution from cognitive software updates. In this view, the brain hardware was in place by ~100k years ago, but the software of self-aware, recursive thinking was only “installed” later – via a cultural innovation (the discovery of introspection and its transmission through ritual). This allows the timing of the actual consciousness shift to align with the archaeological evidence for sudden flourishing of culture. Cutler argues that truly modern behavior (rich art, religion, structured language) could have appeared “wherever the data suggest,” once the genetic constraint is removed. The data indeed suggest it appeared relatively late (Upper Paleolithic to Mesolithic). By proposing that “the concept of ‘self’ was discovered and diffused memetically via psychedelic ritual”, the SC/EToC model places the awakening of full self-awareness at around the end of the Ice Age (~15,000 years ago). This timing neatly fits several independent observations:

- The global flood of creative culture after ~15kya: We see the emergence (or expansion) of cave art in Europe and Indonesia ~30–40kya, but then a mysterious intensification much later – for example, the elaborate cave paintings of Lascaux and Altamira around 17–15kya, the construction of ritual sites like Göbekli Tepe ~11.5kya, and the advent of organized religion and agriculture soon after. It’s as if humanity “woke up” and rapidly transitioned from hunter-gatherer lifestyle to building temples and farms (Colin Renfrew even remarked that the Neolithic Revolution “looks like the true Human Revolution” in terms of mindset). By tying consciousness change to ~15kya, SC/EToC suggests that the end of the Ice Age saw not just climate change but cognitive change. This could explain why temples appear before agriculture in the record (e.g., Göbekli Tepe’s temple predates domesticated wheat) – perhaps a new level of self-awareness and religious thinking spurred the social coordination needed for agriculture. The Sapient Paradox is resolved because our ancestors weren’t fully sapient until this late date, when a cultural spark ignited the tinder of latent capacity.

- Genomic evidence for recent brain-related evolution: For decades, the orthodox view was that the human brain and its cognitive abilities have been genetically static for ~50-100k years, since all living humans share common ancestors in that timeframe. However, cutting-edge paleogenomics is challenging that view. A 2024 ancient-DNA study by Akbari et al. (2024) analyzed genomes from the past 10,000 years and found that strong directional selection on many traits (including possibly cognitive traits) has been “pervasive” in the Holocene. They observed that alleles associated with higher IQ and educational attainment increased significantly in frequency from 10kya to now. In fact, their data suggest that humans 10,000 years ago had a genetic potential IQ notably lower (by ~2 standard deviations on average) than humans today. While one must be cautious interpreting polygenic score differences in ancient DNA, the key point is: measurable cognitive evolution occurred within the last 10 millennia. This demolishes the assumption that “modern brain = 100k-year-old brain”. If selection continued, it implies that some new pressures or advantages kicked in with the rise of civilization. SC/EToC provides a mechanism: once introspective, symbolic culture emerged (via the snake-venom-induced insight), it created a new selective landscape. Individuals and groups who were better at the new “game” of culture – e.g., more capable of recursive thought, language, foresight – had an advantage and left more offspring, driving genetic evolution in those directions. TENM1 is a case in point: this gene (Teneurin-1) shows one of the strongest signals of recent selection (especially on the X-chromosome) in humans. Its function? It “plays a role in regulation of neuroplasticity in the limbic system” and modulates BDNF production. Such a gene could be critical for the brain’s ability to rewire and support abstract thinking. It is tantalizing that TENM1’s effect on BDNF links to the same pathway that snake venom’s NGF might influence. One could speculate that an initial environmental challenge (snakebite provoking a flood of NGF and a neural crisis) could in turn favor genotypes with more robust neuroplastic responses (higher BDNF via TENM1 modulation), thus fixing in the population a greater capacity for stable self-awareness. In other words, gene-culture coevolution would lock in what the snake cult unlocked. This scenario aligns well with the genetic evidence of selection on brain-related loci in the past 10-15k years, including not just TENM1 but others related to brain development, learning, and even speech/language. Recent studies on vocal learning genes (e.g., FOXP2 and regulatory elements in the motor cortex) suggest humans have unique changes enabling complex speech, some of which may have arisen or been honed after the divergence from archaic humans. For example, Wirthlin et al. (2024) found convergent genomic changes in mammals capable of vocal learning (humans, bats, cetaceans), notably losses of certain regulatory DNA in the motor cortex that likely disinhibit the circuits for vocal imitation (a prerequisite for language). This hints that the full flowering of recursive, grammatical language might have required genetic tuning that occurred late. Under SC/EToC, once a cultural innovation (self/“I” and perhaps proto-language to express it) took hold, it would drive selection for brains better at language and recursive thought. In essence, “recursive culture could spread and then cause selection for modern cognition”, as Cutler puts it.

Stoned Ape Theory, in contrast, does not offer a clear mechanism for why such selection would concentrate in the late glacial/early postglacial period. McKenna assumed a continuous beneficial effect of mushrooms over hundreds of thousands of years, which is hard to reconcile with the relatively abrupt “switch-on” of advanced cognition in the archaeological record. Moreover, the timeline McKenna often cited (he speculated mushroom use began with early Homo sapiens or even Homo erectus) would require that all modern humans inherited the effect genetically by common descent. This conflicts with evidence that key genetic changes are more recent or that ancient lineages like Neanderthals did not share our full cognitive suite despite a similar brain size. SC/EToC neatly circumvents this by positing that not all populations needed to independently evolve consciousness – instead, it began in one or a few groups and spread memetically across existing human groups, who then underwent genetic adaptation secondarily. There is support for surprisingly late gene flow and common ancestors in human populations; for example, statistical “most recent common ancestor” of all living humans might be as recent as ~5–7kya (depending on assumptions), indicating there was ample interbreeding and exchange among human groups in the Holocene to spread advantageous genes. Even without interbreeding, a powerful cultural trait like self-awareness and language could spread via emulation, as long as groups encountered each other.

Additionally, SC/EToC addresses the Sapient Paradox by suggesting myths can encode real events up to a certain time depth (perhaps ~10–15k years, as many flood and snake myths seem to), but probably not 100k years. It argues we should trust the widespread myths (serpent in Eden-like stories, primordial mother, etc.) as reflecting a late Pleistocene cultural revolution, rather than stretching them to 100k+ years ago. The timeline of ~15kya also fits with the end of the last glacial maximum and dramatic climate changes that could have pressured human societies into new survival strategies (some hypothesize that hardship might drive innovation in religion and social structure, possibly setting the stage for something like a snake-venom initiation to be invented out of desperation or insight).

To summarize the timeline alignment: The Snake Cult/Eve Theory places the emergence of recursive self-consciousness in the window 15,000–10,000 years ago, which coheres with evidence of a late cognitive revolution and ongoing genetic evolution in our species. The Stoned Ape Theory places it much earlier, which struggles to explain the long delay before evidence of “mindful” behavior and is increasingly at odds with new genetic findings showing substantial evolution in brain-related genes long after our species’ origin. The SC/EToC model, by involving gene-culture coevolution, elegantly bridges the gap: first culture changes (venom-induced self-awareness spreads), then genes follow suit, leading to a self-domesticated ape whose brain is optimized for sustained introspective consciousness. This also potentially explains phenomena like the “paradox of schizophrenia” – i.e., why genes predisposing to schizophrenia (a disorder of self-model and reality testing) persist: the same neural features that allow recursive consciousness can, when dysregulated, cause schizotypal experiences (hearing voices, etc.). Cutler has suggested that schizophrenia might be a costly byproduct of evolving a brain that can distinguish self vs. other voices – essentially a trade-off of our recent cognitive upgrade. Such nuances are absent in the Stoned Ape narrative.

The Snake Cult & Eve Theory: Integrating Evidence and Diffusion Dynamics#

The Vectors of Mind blog posts by Andrew Cutler (2023–2025) synthesize the above threads into a coherent thesis. The Eve Theory of Consciousness (EToC) posits that women, being gatherers and handlers of venomous creatures, could have been the first to obtain the reflexive insight “I am,” and then served as teachers of this insight to their communities. The name “Eve” is a nod both to the biblical first woman and to the idea of a “mitochondrial Eve” – a common ancestress – though here it’s more likely a small group of women in one region who initiated the practice. Cutler hypothesizes that one “fateful encounter” involving a woman’s snakebite led to a breakthrough in conscious awareness. Upon surviving and describing her experience (perhaps via nascent language or demonstration), she and others developed a ritual around it – likely involving deliberate snake bites or venom ingestion in controlled settings. This ritual would have been couched in early mythic terms (e.g., a tale of gaining knowledge from a serpent spirit). Crucially, an antidote or protocol to survive the venom would have been part of the package (archaeologically we have little direct evidence, but the persistence of the practice implies methods to reduce mortality, such as using small doses, tourniquets, herbal anti-venoms, or selecting snakes with less deadly venom). Over time, this practice spreads as a secret of a cult – akin to how shamanic initiations spread. As it spreads, the meme of selfhood spreads with it, effectively teaching non-self-aware humans to become self-aware through dramatic ritual. This idea of “consciousness as a taught behavior” finds parallel in Julian Jaynes’ much later Bronze Age scenario (Jaynes, 1976, argued that humans became self-aware only around 1200 BCE, after the breakdown of a bicameral mind – a controversial theory, but similarly suggesting consciousness is a learned, not innate, trait). Cutler extends this to the late Paleolithic, and with a different mechanism (psychedelic ritual rather than societal collapse).

One intriguing line of support comes from comparative linguistics. If self-awareness truly emerged or spread only in the late Pleistocene, one might detect its linguistic traces. Pronouns, especially the first person singular “I”, are fundamental to expressing selfhood. Cutler points out that across the world’s language families, the word for “I/me” often has strikingly similar sounds (commonly m or n sounds). For instance, “I” is mi or me in many diverse languages, or na/nga in others, far more similar than chance would allow. He argues this could be because the concept and word for “I” diffused relatively recently along with consciousness itself. In other words, we did not inherit our pronouns from a common ancestral language 50,000 years ago (in that case they would have diverged beyond recognition), but rather the first-person pronoun spread like a loanword or calque around ~15kya, preserving its form across many tongues. He dubs this the “Primordial Pronoun Postulate” – that humans have had pronouns for only as long as we’ve had self-awareness. While this linguistic hypothesis is unproven and debated, it’s a novel interdisciplinary attempt to date the birth of subjective consciousness via language change. If true, it adds weight to the SC/EToC timeline and suggests a rapid late diffusion (supporting a singular origin rather than multiple independent “inventions” of introspection).

As the snake cult diffused, it would have syncretized with local cultures, possibly transmuting the physical practice (especially in regions without venomous snakes) but retaining the symbolic core. This might explain why later myths keep the symbol of the snake but no longer practice venom use – they may have substituted other entheogens or milder rituals. For example, if a culture moved into a region with psychedelic plants, they might take up a mushroom or root for the initiation rite but still speak of the Serpent Spirit granting the insight. This way, the iconography (snakes) stays even if the pharmacology shifts – which could be why by the time of recorded history, we have many snake-associated mystery cults (like the Greek cult of Sabazius or the Orphic traditions with snakes), yet historians seldom explicitly mention venom ingestion. By then, the venom practice could have become esoteric or defunct, replaced by symbolic reenactments. Cutler notes this scenario as plausible: “if snake venom served a ritual purpose, it would eventually be replaced (perhaps by mushrooms or any other local psychedelic), even if the symbols did not change”. In fact, one could view Stoned Ape Theory not as a rival but as a later chapter: perhaps mushrooms and other psychedelics did contribute to human creativity, but after the initial catalyst of the “snake bite of self-awareness”. Once the idea of chemically induced spiritual experience existed, humans surely experimented with all manner of substances. McKenna himself speculated that after the last Ice Age, as megafauna died out, humans in some areas turned more to plant-based entheogens.

Auxiliary Insights and Rabbit Holes#

In exploring these theories, one encounters a rich tapestry of obscure lore and modern interpretations that, while not definitive evidence, illustrate how deeply the serpent motif and psychoactive quest are embedded in human culture. For instance, David “Ammon” Hillman, a controversial classicist and self-styled pharmacologist (known online as “Lady Babylon”), has argued that ancient mystery cults and even early Christianity employed snake venom for transcendence. Hillman claims to have reinterpreted texts indicating that figures like Medea (the sorceress of Greek myth) used venom both to kill and to enlighten – in his telling, Medea’s “magic” was largely pharmacological, and she could induce out-of-body experiences and grant immunity to venom by controlled dosing (a practice reminiscent of the Mithridatic antidotes in antiquity). He even suggests the early Gnostic Christians or fringe sects might have experimented with venoms as a route to spiritual death-and-rebirth, citing esoteric readings of the Mark 16:18 verse about “taking up serpents” and surviving poison through faith. While most academics view Hillman’s theories skeptically, they interestingly echo the core notion of SC/EToC: that venoms were seen as sacred substances enabling union with the divine. The persistence of venom-handling cults (like certain Pentecostal snake handlers in Appalachia, or tantric rituals in India) shows that even in the modern day, some humans ritualize venom in a spiritual context – a faint echo, perhaps, of a prehistoric origin.

Another curious tangent is the idea that snakes and psychedelics are neurologically linked in perception. Users of DMT and ayahuasca frequently report visions of serpents; one theory in cognitive science (called the “Snake Detection Theory”) posits that primates evolved keen visual detection for snakes, which might be why snakes appear so readily in altered states and dreams. It’s been mused that if early hominins took psychedelics, their strong snake-detection neural circuitry could externalize as visionary serpent imagery – possibly seeding snake myths even if the drug was a mushroom. In other words, a psychedelic ape might see serpents in the mind’s eye and attribute wisdom to them, unintentionally reinforcing snake symbolism. This is a speculative neurotheological twist: the brain’s evolutionary fear of snakes might color its spiritual visions. It could complement SC/EToC by suggesting that once actual snakes (and their venom) were used to spark visions, the visions themselves (being snake-laden) confirmed the snake as the totem of enlightenment.

Conclusion#

Both the Stoned Ape Theory and the Snake Cult/Eve Theory offer bold, non-mainstream explanations for how human consciousness may have reached its modern recursive form. McKenna’s Stoned Ape Theory deserves credit for pioneering the idea that psychedelics could influence evolution, highlighting psilocybin’s profound cognitive effects. It resonates with the modern appreciation of psychedelics as catalysts for creativity and insight, and it brought the discussion of human consciousness evolution into popular culture. However, as an explanatory framework, it remains highly speculative and chronologically vague. It does not account for the nuanced timing of cognitive modernity or the cultural ubiquity of non-mushroom symbols. There is no clear through-line from mushroom ingestion to specific evolutionary outcomes in the archaeological record; at best, it is a plausible contributor to general neuroplasticity over long spans.

The Snake Cult/Eve Theory of Consciousness, by contrast, is a more recent synthesis that attempts to integrate mythology, archaeology, pharmacology, and genetics into a cohesive narrative. It argues that recursive self-awareness was a late cultural innovation, propagated through ritual use of snake venom, and only later cemented by genetic evolution. This theory finds support in the pervasive serpent mythos in human cultures and in emerging evidence that significant brain-related genetic change has occurred in the Holocene. It elegantly addresses the Sapient Paradox by moving the critical transition closer to the present, in line with what the archaeological record (sudden widespread art/religion ~10–15kya) suggests. Moreover, it draws intriguing connections – for example, between venom’s biochemical effects and the neurobiology of consciousness, or between pronoun diffusion and cognitive diffusion – that generate testable hypotheses in linguistics and genetics. While still largely hypothetical, SC/EToC can boast a greater consilience of evidence from diverse domains: a serpent-shaped footprint in our collective myths, and possibly a serpent’s trace in our genomes (if one looks at genes like TENM1 or the enduring enigma of why our cholinergic systems respond to snake toxins).

Importantly, these theories need not be mutually exclusive in an absolute sense. It could be that psychoactive fungi and plants played a supporting role in human cognitive evolution, especially in different regions, but that the first spark – the catalyzing event that allowed “I” to emerge – came from an encounter with an animal psychedelic (venom) at a unique moment in time. The Snake Cult hypothesis has the advantage of being framed as a singular event and subsequent diffusion, which is more in line with how specific, rare inventions (like controlled fire use, or the wheel) entered human practice and then spread. The Stoned Ape idea is more of a broad evolutionary pressure concept, which is harder to pin to discrete cause-effect.

From a scientific standpoint, both theories are challenging to prove. They venture into realms (consciousness, prehistory, myth) where controlled experiments or unequivocal evidence are elusive. Thus, any endorsement must be tempered with caution. However, when held against the criteria of neuropharmacological plausibility, cultural imprint, and timeline coherence, the Snake Cult/Eve Theory currently provides a more comprehensive and interdisciplinary explanation for the rise of human self-awareness. It aligns the biochemical potency of venom with the ancient storytellers’ obsessions and with the geneticists’ newest data on post-Ice Age selection. In doing so, it lends “fangs” to the idea that the secret of Eden’s serpent might lie not in metaphor alone, but in a real psycho-spiritual technology wielded by our ancestors. As one commentator mused, if we entertain the thought that humanity’s awakening was midwifed by a reptile’s bite, we find a satisfying resolution to several puzzles of our origins – and we may look at the serpents in our religious art with a new appreciation for their role in making us conscious, self-reflecting beings.

FAQ#

Q 1. What is the core difference between the Snake Cult/Eve Theory and the Stoned Ape Theory? A. SC/EToC posits a late (~15kya) emergence of recursive consciousness triggered by snake venom rituals and spreading memetically, thus explaining the archaeological lag (“Sapient Paradox”). Stoned Ape Theory proposes earlier cognitive enhancement via psilocybin mushrooms, potentially beginning hundreds of thousands of years ago.

Q 2. Why is serpent mythology considered strong evidence for the Snake Cult theory? A. Serpent symbolism related to knowledge, creation, or transformation is globally ubiquitous in ancient myths, unlike mushroom symbolism. SC/EToC argues this reflects a widespread, diffused cultural memory originating from a serpent-related awakening event, potentially involving venom rituals.

Q 3. How does the Snake Cult theory align with genetic evidence? A. It accommodates recent findings of significant brain-related genetic selection occurring within the last 10-15,000 years (Holocene). This suggests that the cultural innovation (spread of self-awareness via ritual) created new selective pressures, driving subsequent gene-culture coevolution to optimize the brain for recursive thought.

Sources#

- Akbari, N.S. et al. (2024). “Pervasive findings of directional selection realize the promise of ancient DNA to elucidate human adaptation.” bioRxiv, preprint DOI: 10.1101/2024.09.14.613021. (Analysis of ~2,800 ancient human genomes showing widespread selection in the last 10,000 years, including alleles for cognitive traits.)

- Cutler, A. (2023). “The Snake Cult of Consciousness.” Vectors of Mind (Substack blog), Jan 16, 2023. (Original essay introducing the Snake Cult hypothesis – proposing that snake venom-induced self-awareness solved the Sapient Paradox by ~15kya.)

- Cutler, A. (2024). “The Eve Theory of Consciousness.” Seeds of Science (Substack), Nov 20, 2024. (Article detailing EToC v3.0 – argues consciousness is recent, first arising in women via serpent-related ritual, and spread memetically before influencing genetic evolution.)

- Cutler, A. (2025). “The Snake Cult of Consciousness – Two Years Later.” Vectors of Mind (Substack blog), ~Feb 2025. (Follow-up post reviewing evidence for the theory: notes on modern snake venom use, comparative mythology, and expert parallels like Froese’s ritual model.)

- Froese, T. (2015). “The ritualised mind alteration hypothesis of the origins and evolution of the symbolic human mind.” Rock Art Research 32(1): 94-107. (Proposes that Upper Paleolithic shamanic rituals — involving psychedelic substances, ordeals, etc. — were used to facilitate the development of reflective subject–object consciousness in youths, which later became internalized through gene-culture coevolution.)

- Mehrpour, O., Akbari, A., Nakhaee, S. et al. (2018). “A case report of a patient with visual hallucinations following snakebite.” Journal of Surgery and Trauma 6: 73–76. (Documents a rare incidence of vivid hallucinations in a 19-year-old male after envenomation; suggests neurotoxic snake venom can induce psychotropic symptoms.)

- Senthilkumaran, S., Thirumalaikolundusubramanian, P., & Paramasivam, P. (2021). “Visual Hallucinations After a Russell’s Viper Bite.” Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 32(4): 433–435. DOI: 10.1016/j.wem.2021.04.010. (Case study of a 55-year-old woman who experienced visual hallucinations and delusions following a viper bite; notes such neuropsychiatric manifestations are exceedingly rare in snakebite cases.)

- Jadav, D., Shedge, R., Meshram, V.P., & Kanchan, T. (2022). “Snake venom – An unconventional recreational substance for psychonauts in India.” J. of Forensic and Legal Medicine 91: 102398. (Reports on the emerging trend of snake venom use as a recreational drug in India, including a case of a man using cobra bites to achieve weeks-long highs and relief from opioid addiction.)

- Renfrew, C. (2007). Prehistory: The Making of the Human Mind. Cambridge Univ. Press. (Introduces the Sapient Paradox – highlighting the gap between anatomically modern humans and late cultural flowering – and discusses the role of symbolism and sedentism in the emergence of civilization ~10kya.)

- Witzel, E.J.M. (2012). The Origins of the World’s Mythologies. Oxford Univ. Press. (Proposes that many global mythological motifs derive from two ancient source traditions – “Laurasian” myths possibly tracing back to early modern humans leaving Africa. Suggests serpent-centric creation stories might go back >50,000 years, though acknowledges the challenges of such longevity.)

- Wynn, T. & Coolidge, F. (2011). How To Think Like a Neandertal. Oxford Univ. Press. (Cognitive archaeology perspective; Wynn has noted that clear evidence of abstract/symbolic thought is essentially absent prior to the Upper Paleolithic, e.g., he places the first art and probable abstract thinking around 16kya.)

- McKenna, T. (1992). Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge. Bantam Books. (Develops the Stoned Ape Theory, arguing that regular consumption of psilocybin mushrooms by human ancestors catalyzed the development of language, religion, and consciousness in the Pleistocene.)

- Pollan, M. (2018). How to Change Your Mind. Penguin Press. (Discusses modern psychedelic science and history; casts doubt on the Stoned Ape Theory, calling it an intriguing but unproven speculation – Pollan notes that while psychedelics can occasion mind-opening experiences, there’s scant evidence they drove evolutionary changes in early humans.)

- Hillman, D.C.A. (2023). Lecture series on ancient psychoactive rituals (via Koncrete Podcast and YouTube “LadyBabylon” channel). (Hillman – a controversial scholar – asserts that Greek and early Christian rites used serpent venom and other drugs for transcendent experiences. Claims mythic figures like Medea practiced venom immunization and that early Christians symbolically “took up serpents” as a sacrament. Lacks mainstream acceptance but reflects ongoing fringe interest in venom as entheogen.)

- Wirthlin, M.E. et al. (2024). “Vocal learning-associated convergent evolution in mammalian proteins and regulatory elements.” Science 383(6690): eabn3263. DOI: 10.1126/science.abn3263. (Found that distantly related vocal-learning mammals share genetic changes – notably in gene regulation in brain – that non-learners lack. Supports the idea that human speech ability has specific genetic underpinnings that evolved, potentially relatively recently in our lineage, enabling full grammatical language.)

- Frobenius, L. (1921). Und Afrika Sprach (field notes, Bassari myth) – as cited in Witzel (2012) and Cutler (2025). (Leo Frobenius recorded the Bassari people’s Eden-like creation myth involving a snake and a loss of primordial paradise. Not widely published in English, but often referenced as evidence of parallel myth-making independent of Abrahamic influence.)

- Nemo, A. (2022). “Psychoactives in Ancient Egypt: The Mushroom Myths.” Artistic Licence blog. (A skeptical takedown of pseudo-archaeological claims regarding mushroom and snake symbolism in Egypt. Emphasizes the lack of solid evidence for those claims and warns against confirmation bias in entheogenic historiography.)