TL;DR

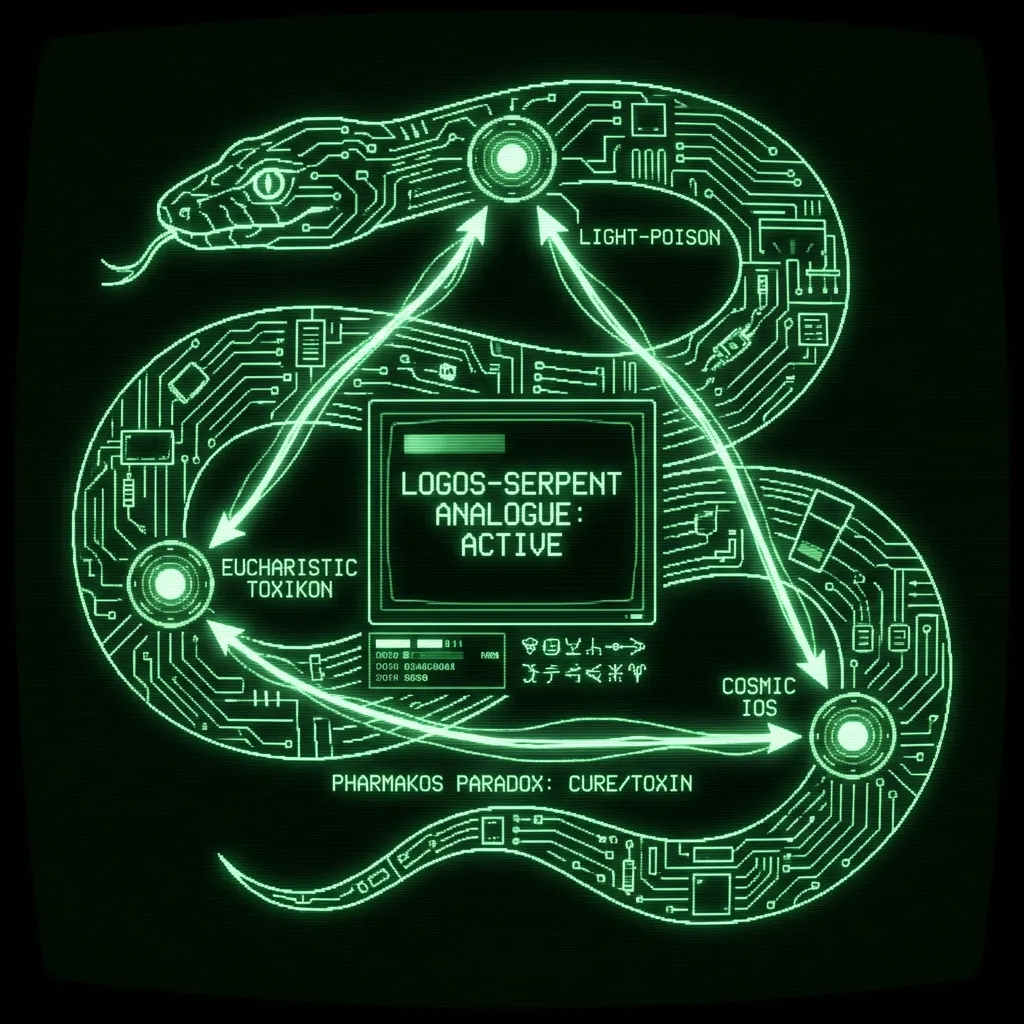

- Three seminal ophidian texts—Kephalaia 144 (Manichaean), Panarion 37.4 (Ophite via Epiphanius), and the Naassene Hymn quoted by Hippolytus—frame Christ-as-Serpent in pharmacological language.

- None celebrates literal snake-handling; each exploits the double sense of φάρμακον / samā / ios (“drug, poison, cure”) to dramatise salvation via inversion.

- Manichaeans weaponise light as a corrosive “poison” against Archons; Ophites (as caricatured) allegedly spike the Eucharist with ophidian “blood”; Naassenes sing of a cosmic venom that is honey to the elect, toxin to the rest.

- All three rely on John 3:14 + Num 21 (bronze serpent) and on Greco-Egyptian medical lore in which the cure is distilled from the sting.

- Patristic polemic (Epiphanius, Augustine) mirrors the trope: they brand heresy itself a virus—ironically preserving the pharmacological motif they abhor.

1 Why venom? A synthetic overview (≈ 500 words)#

Early Christian exegesis found a ready-made type for the crucifixion in Moses’ bronze serpent (Num 21 → John 3:14). Mainline writers (Justin, Irenaeus) kept the Eden-serpent satanic yet embraced the bronze image as a life-giver: “look at what bit you and be healed.”

Gnostic and dualist currents push the logic further: if the bronze copy heals, the living prototype must be stronger still. The serpent ceases to be an antetype and becomes identical with the Logos—a daring collapse of typology.

Philosophically, the move taps the Greek ambiguity of φάρμακον (pharmakon): cure, drug, poison, scapegoat. Plato’s Phaedrus (274e) already plays on the word; Egyptian temple medicine brewed antidotes from viper gall; Ptolemaic alchemists spoke of σύσμιγμα (commixture) where a toxin “kills itself.”

Gnostics seize that rhetoric:

The same sting that kills hylic flesh awakens pneumatic mind; the Demiurge’s quarantine is breached by a paradoxical medicine smuggled in the serpent’s mouth.

What follows are three case-studies where that inversion crystallises: Manichaean Light-Poison, Ophite Eucharistic Toxikon, Naassene Cosmic Venom.

2 Manichaean “poison of light” (Kephalaia 144) (≈ 700 words)

2.1 Text & Translation#

Syriac (ed. Polotsky) ܘܡܠܐ ܝܫܘܥ ܕܢܘܗܪܐ ܣܡܐ ܕܢܗܝܪܐ ܒܦܘܡ ܕܚܘܝܐ ܘܫܬܘ ܐܪ̈ܟܘܢܐ ܘܐܬܚܠܫܘ

My English rendering “And Jesus the Splendour poured a poison of light into the serpent’s mouth; the Archons drank and were enfeebled.”

2.2 Setting in the Manichaean myth-cycle#

- Primal Jesus descends to Eden as a Luminous Envoy to reclaim scattered light-particles.

- Edenic serpent = instrument not adversary. Jesus fortifies it with dazzling “toxin”; Eve (carrier of light) transmits the mixture to the Archons who ingest it, causing systemic collapse.

- Result: photons of Soul leak back toward the Father of Greatness—Mani’s soteriology in microcosm.

2.3 Philological notes#

- Syriac ܣܡܐ (samā) mirrors Greek φάρμακον; classical Syriac medical papyri use it for both snake-venom and antidote.

- The genitive “of light” tweaks the idiom: not poison that gives light but light that poisons the dark powers—an exquisitely dualist inversion.

2.4 Reception & legacy#

Augustine’s De Hæresibus 46 paraphrases the passage to vilify Mani: “virus lucis in ore serpentis.” Modern scholarship (BeDuhn 2000) reads it as ritual dramatisation inside catechetical homilies, not a literal venom rite.

3 Ophite Eucharistic toxikon (Epiphanius, Panarion 37.4) (≈ 700 words)

3.1 Greek source & translation#

Greek

“…εἰς τὸ ποτήριον ἐγχέοντες τὸ τοξικὸν τοῦ ὄφεως, λέγουσιν αὐτὸ εἶναι τὸ αἷμα τοῦ Χριστοῦ.”Translation

“They pour the toxikon of the serpent into the chalice, declaring it the blood of Christ.”

3.2 Who were the Ophites?#

Named from ὄφις (“snake”), they appear in Celsus, Irenaeus, and Epiphanius (who bundles them with Cainites). Their myth exalts the Edenic serpent as Sophia’s vessel; the Demiurge is a blind lion-face. The Eucharistic charge sits in Epiphanius’ catalogue of horrors: consuming menstrual blood, worshipping reptiles, etc.—classic heresiographical mud-slinging.

3.3 Assessing credibility#

| Criterion | Observation |

|---|---|

| Internal corroboration | None. No surviving Ophite tract mentions literal venom. |

| Heresiarch’s style | Epiphanius employs pharmacist metaphors throughout Panarion (the very title = “antidote chest”). Likely rhetorical. |

| Ritual plausibility | Egyptian magico-medical papyri include snake-bile in potions; the leap to Eucharistic use is sensational but not impossible. |

3.4 Symbolic logic behind the smear#

- If Christ = serpent, the chalice = serpent’s blood.

- Toxikon originally meant bow-poison on arrows (φάρμακον τοξικόν). By the 4th c. it evokes both venom and drug.

- Epiphanius weaponises audience disgust toward blood-drinking and ophidiophobia to seal his orthodoxy.

3.5 Modern readings#

- Rasimus (2007) calls the passage a polemical mirror: Epiphanius projects his fear that Gnostics reverse every symbol, so the cup of salvation becomes a chalice of venom.

- Still, a minority (Marjanen 2019) wonders if trace venom in ritual might dramatise immunity—echoing Mark 16:18 (“they shall drink any deadly thing, and it shall not hurt them”).

4 Naassene cosmic ios (Hippolytus, Refut. 5.8-9) (≈ 700 words)

4.1 Critical text & translation#

Greek

“ὁ ἀόρατος καὶ ἄρρητος Ἄνθρωπος τρία ἑαυτὸν διεῖλεν· … τὸ τρίτον ὡς ἰὸς διὰ πάντων ἐρρύη, γλυκὺς μὲν ἐκλεκτοῖς, πικρὸς δὲ τοῖς ἄλλοις.”Translation

“The Invisible, Ineffable Man divided himself thrice… the third part streamed as venom (ios) through all things—sweet as honey for the elect, bitter poison for the rest.”

4.2 Liturgical frame#

Hippolytus cites a Naassene festival hymn (likely Phrygian) describing cosmogenesis:

- Proto-Anthropos splits into Mind, Soul, Venom.

- The Venom flows into matter, animating yet enslaving it.

- Christ-Serpent recapitulates this third stream, drawing it back as honey for pneumatics.

4.3 Theological stakes#

- Ambivalent agency: venom is neither purely evil nor purely good; efficacy depends on gnosis.

- Syzygic triads: the threefold division mirrors Valentinian aeons; the Naassene spin accentuates taste: honey vs. bile.

- Comparison: John 19’s gall-vinegar offered to Jesus becomes a counter-type—bitter to soldiers, sweet to the crucified.

4.4 Philological excursus on ios#

- Classical Greek ἰός = arrow-poison, virus, rust.

- Hippocratic texts call snake-venom ἰὸς ὄφεως, treating it with honey-vinegar.

- Naassenes riff on medical commonplaces: venom turned sweet by divine alchemy.

4.5 Reception#

- Hippolytus dismisses hymn as “honey-dipped fable concealing stings.”

- Modern interpreters (Turner 1993) see early Christian-Hermetic fusion: cosmic circulation, microcosmic palate (sweet/bitter), and mystery-cult initiations involving psychedelic mead.

5 Synoptic comparison & wider echoes (≈ 400 words)#

| Axis | Manichaean | Ophite (Epiph.) | Naassene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | Light-toxin | Eucharistic cup | Cosmic lifeblood |

| Target of venom | Archons | Communicants (salvific per sect, deadly per Epiph.) | Hylic masses |

| Lexeme | Syr. samā | Gk. toxikon | Gk. ios |

| Mode | Weaponised brilliance | Liturgical parody | Ontological circulant |

| Patristic source | Augustine summarises, quotes lost Mani original | Epiphanius, entirely hostile | Hippolytus quotes Naassene self-text |

Take-home: one myth, three valences—military (Mani), sacramental (Ophite), cosmogenic (Naassene)—yet all lean on the same pharmakon dialectic.

FAQ #

Q 1. Did any group literally drink snake venom?

A. No firm evidence. Epiphanius’ claim is uncorroborated. The pharmacological language is symbolic, playing on “cure-through-poison” rhetoric common in Greco-Egyptian medicine.

Q 2. Why “poison of light” in Manichaeism?

A. Because light, for Mani, is ontologically opposite to dark matter; to Darkness it burns like acid. The phrase dramatizes a cosmic chemical warfare.

Q 3. Does the Naassene hymn reflect actual liturgy?

A. Likely—Hippolytus quotes it as chanted material, complete with rhythmic cola; its sensory imagery (honey vs. bitter) suits initiation rites.

Q 4. Are there parallels in canonical texts?

A. Mark 16:18 promises immunity from venom; John 3:14 reads bronze serpent typologically. Gnostics radicalise both: the snake is no longer symbol but subject.

Footnotes#

Sources#

- Polotsky, H.-J. Manichäische Homilien und Kephalaia. Berlin, 1940.

- Epiphanius of Salamis. Panarion, ed. Holl; tr. Williams, Brill 1987–2009.

- Hippolytus. Refutatio Omnium Haeresium V, ed. Marcovich, GCS 43 (1986).

- BeDuhn, Jason. The Manichaean Body. Johns Hopkins, 2000.

- Rasimus, Tuomas. “Snake Worship and Pelagic Polemic,” Vigiliae Christianae 61 (2007): 431-458.

- Turner, John D. “The Naassene Sermon Reconsidered,” VC 47 (1993): 235-244.

- Marjanen, Antti. “Toxikon and Eucharist,” JECS 27 (2019): 155-184.

- Derrida, Jacques. “La pharmacie de Platon,” Tel Quel 32 (1968): 3-48.

- Graf, Fritz. Magic in the Ancient World. Harvard UP, 1997 (on venom antidotes).