TL;DR

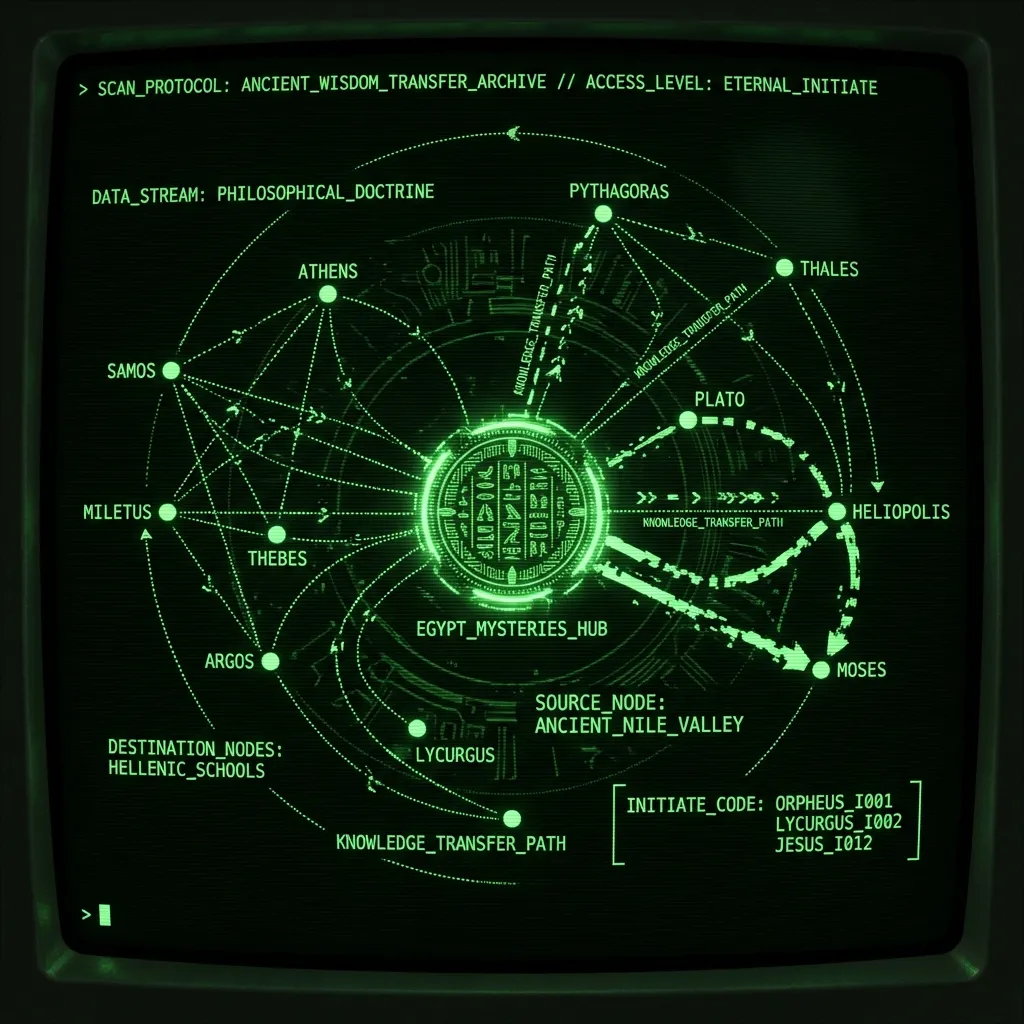

- Ancient Egypt was renowned as the ultimate repository of arcane wisdom, drawing sages from across the ancient world to learn its “mysteries.”

- Legendary figures like Orpheus, Moses, and Lycurgus allegedly gained theological, mathematical, and political wisdom from Egyptian priests.

- Greek philosophers including Thales, Solon, Pythagoras, Plato, and Democritus traveled to Egypt, returning with geometric knowledge, astronomical insights, and philosophical doctrines.

- Later figures from Apollonius of Tyana to Christian Rosenkreuz continued this tradition into the medieval and early modern periods.

- Jesus’s childhood flight to Egypt fits this archetypal pattern of wise figures being touched by Egypt’s mystical heritage.

- The continuous theme across millennia: “Going to Egypt to learn the mysteries” was a mark of honor and the ultimate source of ancient knowledge.

Introduction#

Ancient Egypt was fabled as a repository of arcane wisdom. From legendary poets to philosophers and even religious figures, many sages were said to journey to Egypt to learn the “mysteries” – secret knowledge of religion, science, or magic. Below is an exhaustive list of such figures (both historical and legendary), along with what each purportedly learned in Egypt, showing how Jesus’s childhood sojourn fits into this longstanding tradition.

Mythic and Legendary Sages

Orpheus (legendary poet)#

In Greek myth, Orpheus journeyed to Egypt and was initiated into the mysteries of Osiris/Dionysus. Diodorus Siculus recounts that Orpheus adopted the Egyptian rites of Dionysus and brought them back to Greece, effectively transplanting those mystery rituals to Thebes. The doctrines Orpheus learned in Egyptian sanctuaries allegedly included theological principles (e.g. the unity of God above lesser gods) and secret rites, which formed the basis of the Orphic Mysteries in Greece.

Moses (Hebrew lawgiver)#

Although Moses was born in Egypt, tradition emphasizes that he was “educated in all the wisdom of the Egyptians”. The New Testament notes this explicitly (Acts 7:22), and commentators explain that Egyptian wisdom encompassed subjects like geometry, astronomy, medicine, and esoteric knowledge. Later legends even credit Moses with Egyptian occult knowledge – for example, he is portrayed as outperforming Pharaoh’s magicians (e.g. Jannes and Jambres) in the Bible, suggesting he had mastered their arts. In Hellenistic Jewish and Christian thought, Moses often symbolized the transmission of Egyptian learning into Hebrew tradition.

Lycurgus (Spartan lawgiver)#

The semi-legendary Lycurgus, who gave Sparta its laws, was also said to have traveled widely. Plutarch reports that “the Egyptians think that Lycurgus visited them” and admired how Egyptian society separated the military class from others. Lycurgus allegedly borrowed the idea of a warrior caste – removing artisans and traders from governance – to enforce Spartan social discipline. This suggests he learned statecraft “mysteries” in Egypt, applying Egyptian political wisdom (a strict class system and austere lifestyle) to his Spartan reforms.

Early Greek Philosophers and Sages

Thales of Miletus (c. 6th century BC)#

One of Greece’s Seven Sages, Thales is often credited with bringing geometric and astronomical knowledge from Egypt. Later biographers relate that Thales studied with priests in Egypt and even advised his pupil Pythagoras to go there. Iamblichus writes that Thales “confessed that the instruction of [the Egyptian] priests was the source of his own reputation for wisdom.” He urged Pythagoras to get in touch with the priests of Memphis and Thebes. Indeed, Thales likely learned practical geometry in Egypt – Herodotus notes that the Egyptians had to survey land after Nile floods, a skill Thales introduced to Greece. Thus Thales’ famed theorem and astronomical predictions were attributed to Egyptian training.

Solon of Athens (c. 590 BC)#

The Athenian lawgiver Solon visited Egypt and studied under Egyptian priests. Plutarch recounts that Solon spent time in study with Psenophis of Heliopolis and Sonchis of Saïs, “who were very learned priests.” From them, “he heard the story of the lost Atlantis”, which he later tried to poetically transmit to the Greeks. According to this tradition (later immortalized in Plato’s Timaeus), Egypt’s priests possessed records of ancient cataclysms forgotten by Greeks. Beyond Atlantis, Solon likely absorbed a general sense of Egypt’s antiquity and wisdom; Egyptian influences may have informed his own reforms. In sum, Solon’s Egyptian sojourn connected Athens to the deep historical knowledge kept in Egyptian temples.

Cleobulus of Lindos (6th century BC)#

Another of the Seven Sages of Greece, Cleobulus also “traveled, in his youth, to Egypt, where he was taught philosophy by the mystic priests.” Sources note “he studied philosophy in Egypt” and was renowned for wisdom and riddles. His daughter Cleobulina later became a noted riddler as well, suggesting an Egyptian influence on enigmatic wisdom literature. Cleobulus’ teachings (e.g. maxims on moderation, learning, and self-control ) may have been enriched by philosophical lore from Egyptian temples.

Pythagoras of Samos (fl. 6th century BC)#

Perhaps the most famous case, Pythagoras traveled to Egypt for initiation into its mysteries. Later biographies (by Porphyry and Iamblichus) claim he spent over 20 years in Egypt learning from priests. Iamblichus describes how “in Egypt he frequented all the sanctuaries with the greatest diligence…winning the esteem of all the priests,” and he “acquired all the wisdom each possessed.” Among the teachings Pythagoras gleaned were geometry and astronomy – Egypt’s priests taught him their knowledge of celestial cycles and land surveying. He was even said to be initiated at Thebes, the only foreigner ever allowed to partake in Egyptian temple worship. Pythagoras’ doctrine of metempsychosis (transmigration of souls) was attributed to Egyptian beliefs, and his famed mathematics and musical theories likewise echoed Egyptian and Eastern insights. In short, later Greeks saw Pythagoras’ philosophy as a syncretic “mystery wisdom” – “a synthesis of everything Pythagoras had learned from Orpheus, from the Egyptian priests, [and] the Eleusinian Mysteries,” as Iamblichus put it.

Herodotus of Halicarnassus (5th century BC)#

The Greek historian Herodotus might not be a “sage” in the same mold, but he traveled to Egypt to gather knowledge and is a primary source on Egyptian lore. In Histories Book II, Herodotus reports that “from the priests at Memphis, Heliopolis, and Thebes he learned” about Egypt’s geography, the Nile, religious rites, and history. He hints that the priests even entrusted him with secret lore on certain gods – at one point he refuses to elaborate on Osiris because “I know it, but I must not say”. Herodotus openly admired Egyptian wisdom, claiming “the Egyptians are wise” and that the Greeks borrowed many customs from them. Thus Herodotus’ sojourn exemplifies the Greek view of Egypt as the fount of ancient religious and historical “mysteries.”

Democritus of Abdera (5th century BC)#

The philosopher Democritus, famous for atomic theory, undertook extensive travels in pursuit of knowledge. Ancient accounts say he “spent the inheritance his father left him on travels into distant countries” for learning’s sake. He “must also have visited Egypt,” and Diodorus Siculus even states Democritus “lived there for five years.” During this time he consulted with “Egyptian mathematicians, whose knowledge he praises.” Democritus himself boasted that no one had traveled more or met more scholars than he, “among whom he mentions in particular the Egyptian priests”. From them, he learned geometry and cosmology – later writers note that Democritus wrote about Egyptian sacred knowledge (theology) and acknowledged the Egyptians’ skill in mathematics. In sum, Democritus is portrayed as absorbing scientific and mystical lore in Egypt (and Babylon, Persia, even India) to become the most erudite of philosophers.

Plato of Athens (428–347 BC)#

The great philosopher Plato is also linked to the Egyptian-wisdom tradition. After Socrates’ death, Plato traveled abroad for about 12 years, and later accounts include a sojourn in Egypt as part of his travels. He reportedly visited Heliopolis and perhaps met priests there. According to Diogenes Laertius, Plato “proceeded to Egypt, where he admired the ancient wisdom” of the priests. While details are sparse, it’s said he studied geometry and astronomy with Egyptian sages (one tradition claims he learned from the priests of Heliopolis just as his friend Eudoxus did). In fact, Plato’s own dialogues attest to Egyptian influence: in the Timaeus he has an Egyptian priest relate the tale of Atlantis (passed down via Solon) and emphasizes that Egyptian civilization preserved prehistoric wisdom. A later writer, Philostratus, even remarked that “Plato went to Egypt and mixed into his own discourses much of what he heard from the prophets and priests there.” Thus, Plato’s philosophy – especially its emphasis on eternal forms and cosmic order – was seen as enriched by Egyptian cosmology and theology. (Notably, Plato’s pupil Eudoxus of Cnidus did spend 16 months in Egypt studying astronomy under the priests of Heliopolis, refining the astronomical knowledge that would inform Plato’s later work.)

Eudoxus of Cnidus (c. 390–337 BC)#

A student of Plato and a renowned astronomer, Eudoxus went to Egypt specifically to learn astronomy. He spent over a year in Heliopolis, where “he studied astronomy with the priests” and even used their observatory to chart stars. Eudoxus absorbed the Egyptian observations of the heavens (their knowledge of fixed stars and planetary cycles) and on returning to Greece, he revolutionized Greek astronomy. His model of celestial spheres and his calendar studies were clearly informed by Egyptian astronomical records. Thus Eudoxus is a concrete historical example of acquiring scientific “mysteries” (in this case, advanced astronomical data and techniques) from Egyptian temple scholars.

Later Figures and Christian-era Traditions

Apollonius of Tyana (1st century AD)#

Apollonius was a wandering philosopher and miracle-worker often compared to Jesus. Philostratus’s 3rd-century biography depicts Apollonius traveling widely in search of esoteric wisdom. Not only did Apollonius visit Mesopotamia and India (learning from Persian Magi and Indian Brahmans), but he also spent time in Egypt and Ethiopia. In the narrative, Apollonius debates with Egyptian priests and is present at Egyptian shrines performing rites. One modern summary notes that “Apollonius’s gifts of foresight were given to him through studying with the Brahmans of India and Egyptian philosophers.” Indeed, Philostratus claims Apollonius gained his miraculous abilities through wisdom learned from Indian sages and Egyptian priests, rather than through sorcery. Later legend (recorded by G.R.S. Mead) even says Apollonius spent his final years in Egypt’s sanctuaries, immersed in secret rites. In short, Apollonius’s life was cast as a grand tour of the world’s wisdom traditions – with Egypt as a key stop where he deepened his Pythagorean philosophy and learned mystical arts (such as healing, prophecy, and temple reform) from Egyptian sources.

Jesus of Nazareth (1st century AD)#

Jesus differs from the above in that he traveled to Egypt as a child rather than as a scholarly seeker. Nonetheless, his flight into Egypt as an infant (with Joseph and Mary, to escape King Herod’s persecution) is seen by some writers as symbolically linking him to the tradition of Egyptian wisdom. The Gospel of Matthew records that the Holy Family sojourned in Egypt until Herod’s death. While canonical texts are silent on Jesus’s activities there, later apocryphal legends claim the infant Jesus performed miracles on Egyptian soil (toppling idols) – suggesting even in childhood he “enlightened” Egypt. More relevant is a polemical claim from ancient critics: the 2nd-century writer Celsus alleged that Jesus learned magical arts in Egypt during his youth. Origen, quoting Celsus’s accusation, writes: “Celsus…alleges that Jesus performed only what He had learned among the Egyptians.” This hostile charge (that Jesus’s miracles derived from Egyptian sorcery) indicates a tradition that Jesus gained secret knowledge in Egypt – effectively counting him among those who drew on Egyptian “mysteries.” In esoteric Christian circles, there are similar themes (e.g. medieval legends of Jesus visiting the Egyptian Therapeutae or learning from esoteric schools). Thus, Jesus’s time in Egypt, though as a child, is often woven into the continuum of wise figures touched by Egypt’s mystical heritage. It fulfills the prophetic idea “Out of Egypt I called My Son,” while aligning with the pattern of Egypt as a crucible for wisdom even for the savior figure.

Medieval and Early Modern Esoteric Seekers

Hermetic and Gnostic Teachers (1st–4th century)#

A broader esoteric tradition held that Egypt’s mysteries were transmitted through Hermetic teachers. Hermes Trismegistus, the legendary Egyptian sage (identified with the god Thoth), was believed to have authored mystical texts (the Corpus Hermeticum). Early Gnostic sects and later Neoplatonists in late antiquity revered Egypt as the source of secret wisdom about the cosmos. For example, the 3rd-century philosopher Iamblichus in “On the Mysteries” claims Egyptian priests possessed arcane theurgical knowledge, and Greek sages (including Pythagoras and Plato) were merely initiates of this older Egyptian “Mystery religion”. This laid the groundwork for medieval legends of sages seeking Egypt’s wisdom.

Christian Rosenkreuz (15th century, legendary)#

The (probably fictional) founder of the Rosicrucian Order, Christian Rosenkreuz is said to have traveled in the early 1400s through the Near East to acquire occult wisdom. According to the Fama Fraternitatis (1614), Rosenkreuz’s itinerary included “Damascus, Damcar (Arabia), Egypt, and Fès (Morocco)”, where he was instructed by sages. In Egypt specifically, he spent a short time learning natural sciences (“biology and zoology,” one account says) and “came into possession of much secret wisdom.” By the time he returned to Europe, Rosenkreuz had absorbed the esoteric teachings of Egyptian and Middle Eastern masters, which formed the basis of Rosicrucian alchemy and mysticism. His story explicitly casts Egypt as a stop for initiatic training in alchemy, magic, and Kabbalistic-like wisdom, continuing the trope well into the Renaissance.

Athanasius Kircher (17th century scholar)#

Although not a “traveler” in person, Kircher (a Jesuit polymath) was fascinated by Egyptian mysteries. He obtained Egyptian artifacts and texts in Rome and wrote Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1652), an attempt to decipher hieroglyphs and uncover ancient Egyptian theology. Kircher believed Egyptian wisdom (which he called “prisca theologia,” the primordial theology) prefigured Christianity. In a sense, Kircher intellectually “went to Egypt” by immersing himself in its mysteries – translating the Hermetic Corpus and studying Isis-Osiris mythology. His work influenced early modern occult and Masonic groups who saw Egypt as the wellspring of arcane knowledge. (For instance, Kircher claimed Moses and Orpheus drew on Egyptian wisdom, reinforcing that narrative.)

Count Alessandro Cagliostro (18th century)#

A colorful occultist and self-styled mage, Cagliostro explicitly invoked Egyptian initiation in his teachings. He founded an “Egyptian Rite” of Freemasonry and claimed to possess “the secrets of the Egyptian priests”. According to his memoirs, Cagliostro traveled through the East (perhaps including Egypt) as a young man and was initiated by a mysterious master (sometimes named Althotas). One Rosicrucian source recounts that he underwent an initiation in the Great Pyramid of Egypt, experiencing illumination. Cagliostro’s Egyptian Rite ceremonies involved pseudo-Egyptian symbolism (pyramids, sphinxes, etc.) and promised healing elixirs and immortality – said to derive from ancient Egyptian magic. While much of his biography is dubious, Cagliostro’s notoriety shows the continued allure of Egypt. 18th-century Europeans, from occultists like Cagliostro to scholars like Champollion (who cracked hieroglyphics), all saw Egypt as the keeper of primeval mysteries waiting to be rediscovered or exploited.

Freemasons and Occult Revival (18th–19th centuries)#

Beyond Cagliostro, many Enlightenment-era secret societies latched onto Egyptian motifs. Freemasonry’s high-degree rites, such as the Rite of Memphis-Misraim, styled themselves as heirs to the “Egyptian Mysteries”. They concocted legends that the wisdom of Solomon and Moses came from Egyptian initiation, and that Masonic ritual perpetuates pharaonic temple rites. For example, the 19th-century Freemason Albert Pike wrote that Greek philosophers “were initiated in Egypt” and that Masonic symbolism traces back to Egyptian teachings on the unity of God and immortality of the soul. In literature, novels like “Zenobia” or Bulwer-Lytton’s “The Coming Race” referenced sages learning occult secrets in Egypt. By the late 19th century, the Theosophical Society and other occult groups further popularized the idea – speaking of “Masters of Wisdom” in the East (sometimes specifically in Egypt or its deserts) who trained selected Western adepts. In short, the mystique of Egypt as the cradle of hidden wisdom persisted, inspiring generations of “seekers” long after antiquity.

Conclusion#

From Antiquity through the Renaissance, Egypt’s fame as the mother of mysteries drew sage after sage – whether real philosophers like Thales, Pythagoras, Plato, and Democritus, or legendary figures like Orpheus and Hermes. They went (or were said to go) to Egyptian sanctuaries and returned with profound teachings: mathematical knowledge, principles of theology and law, initiation into rites of the gods, and esoteric skills like astrology or magic. Even foundational biblical characters – Moses and Jesus – were woven into this pattern, depicted as steeped in Egyptian wisdom (or in Jesus’s case, at least touching Egypt’s soil as part of divine destiny). In the medieval and early modern era, this tradition was consciously revived by esoteric orders (Rosicrucians, Freemasons, Theosophists), who either mythologized their founders as traveling to Egypt or symbolically traced their secret doctrines back to Egyptian origins.

All these examples reinforce a continuous theme: “Going to Egypt to learn the mysteries” was a mark of honor for a wise man. It signified tapping into the most ancient source of knowledge available. Whether it was Solon hearing of Atlantis from Saïte priests, Pythagoras learning the secret harmony of the cosmos at Thebes, or Renaissance occultists seeking Hermes’s magic, Egypt represented the ancient wisdom tradition par excellence. Jesus’s childhood flight can thus be seen as fitting this archetype – later interpreted (by detractors like Celsus and some esoteric authors) as Jesus having imbibed Egypt’s secret lore. True or not, the perception is what mattered: throughout Western history, Egypt was the teacher of wise men, and the journey to Egypt – whether physical or intellectual – was the rite of passage into the Mysteries of the ages.

FAQ#

Q: Were all these accounts of sages traveling to Egypt historically accurate? A: Many of these accounts are legendary or semi-legendary, particularly the earliest ones (Orpheus, early Greek sages). Some have stronger historical basis (Herodotus definitely visited Egypt, Eudoxus likely did), while others reflect later traditions that may have embellished or invented Egyptian connections to lend authority to various teachings.

Q: What specific knowledge were these sages said to gain in Egypt? A: The knowledge varied but commonly included: geometry and mathematics (land surveying techniques), astronomy (celestial observations and calendar systems), medicine and healing arts, religious and theological doctrines (especially about afterlife and soul transmigration), magical practices, and political/social organization principles.

Q: Why was Egypt specifically seen as the source of ancient wisdom? A: Egypt’s extreme antiquity, impressive monuments, sophisticated priest class, preserved written records, and stable civilization over millennia made it appear to Greeks and later cultures as the repository of primordial knowledge. Its priests were seen as guardians of secrets stretching back to the dawn of civilization.

Q: How does Jesus’s childhood in Egypt fit this pattern? A: While Jesus went to Egypt as a refugee child rather than a wisdom-seeker, later traditions (both hostile like Celsus’s accusations and esoteric Christian legends) connected his time there to the broader pattern of acquiring Egyptian wisdom. This fulfilled both biblical prophecy (“Out of Egypt I called my son”) and the archetypal narrative of Egypt as a formative spiritual environment.

Q: Did this tradition continue beyond antiquity? A: Yes, the mystique of Egyptian wisdom persisted through medieval times (Hermetic traditions), the Renaissance (Rosicrucian legends), the Enlightenment (Masonic Egyptian rites), and into modern occultism (Theosophical Society). Each era reinterpreted Egyptian mysteries according to contemporary spiritual and intellectual needs.

Sources#

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 1.27–29 (1st c. BC) – on Orpheus adopting Egyptian mysteries.

- Plutarch, Life of Solon 26.1 – Solon’s studies with Egyptian priests Sonchis and Psenophis (Atlantis story).

- Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus 4–5 – Lycurgus’s visit to Egypt and adoption of its social system.

- Iamblichus, On the Pythagorean Life (3rd c. AD) – Pythagoras’s initiation in Egypt (travels advised by Thales).

- Herodotus, Histories Book II (5th c. BC) – Herodotus’s account of Egyptian religion and his reliance on priestly knowledge.

- Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers (3rd c. AD) – anecdotes on Democritus (travels in Egypt, Babylon, etc.) and on Cleobulus.

- “Eudoxus of Cnidus” – MacTutor History of Mathematics (University of St. Andrews) – Eudoxus studying astronomy with priests at Heliopolis.

- Bible, Acts 7:22 – “Moses was instructed in all the wisdom of the Egyptians” (KJV); cf. Bible Hub commentaries describing Egyptian education (geometry, astrology, etc.).

- Origen, Contra Celsum I.28 (3rd c. AD) – quoting Celsus’s claim that Jesus learned magic in Egypt.

- Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana (3rd c. AD), as summarized by Harland (2024) – Apollonius’s study with Indian and Egyptian sages.

- History.com – “Plato” (updated 2025) – Plato’s post-Socrates travels in Italy and Egypt, studying with Pythagoreans like Theodorus.

- Britannica – “Christian Rosenkreuz” – Rosicrucian founder’s travels to Arabia, Egypt, and Fez for secret wisdom.

- Britannica – “illuminati: Early illuminati” – (reiterating Rosenkreuz’s journey including Egypt and acquisition of secret wisdom).

- Benson’s Commentary on Acts 7:22 (via BibleHub) – ancient testimonies about Moses and Egyptian learning (and note that “many Grecian philosophers traveled to Egypt in pursuit of knowledge,” citing Herodotus).