TL;DR

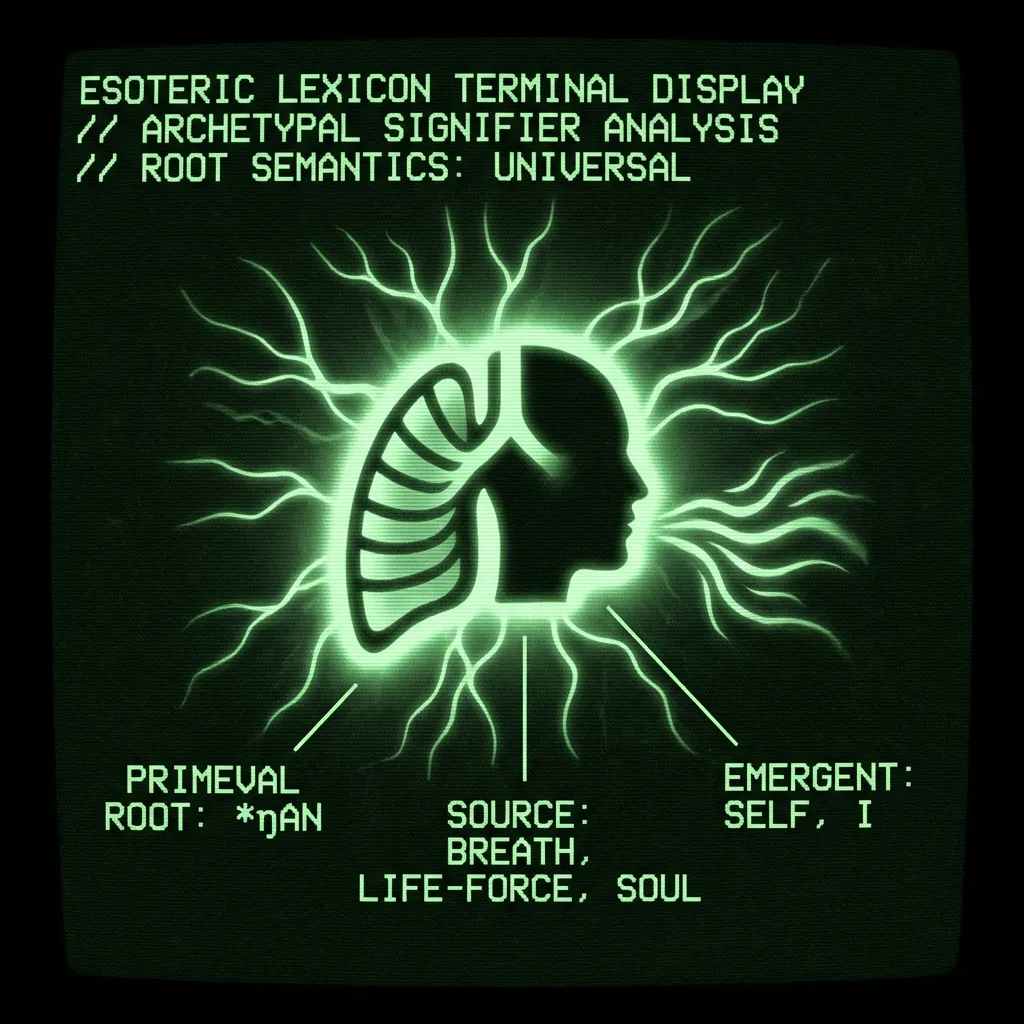

- The *ŋAN hypothesis proposes an ultra-ancient Proto-Sapiens root meaning “breath, life-force, soul.”

- Through regular sound changes (*ŋ > g/k/h/∅), its descendants are found globally in words like PIE *an- (anima), Sino-Tibetan *ŋa (“I”), and Austronesian *qanitu (spirit).

- The semantic evolution from “breath” to “soul” to “self” and even “I” is a common cross-linguistic pathway.

- This speculative reconstruction addresses criticisms of deep-time linguistics by integrating phonosemantic patterns and cultural archetypes.

- While unproven, the hypothesis provides a compelling model for a shared linguistic fossil encoding the link between breath and personhood.

The Ancient Breath of Life: Reconstructing a Proto-Sapiens ŋAN*

Introduction: A Breath That Became the Self#

Human languages across the world share a curious pattern: words for “breath” and “air” often double as words for “spirit”, “soul”, or life itself. This observation underlies a bold hypothesis that an ultra-ancient Proto-Sapiens root, *ŋAN, originally meant “breath, life-force, or soul,” and that through millennia of semantic drift and regular phonological change, its descendants have come to mean “spirit”, “soul”, “person”, and even the first-person pronoun “I” in languages around the globe. In this report, we present the *ŋAN hypothesis in detail. We will outline the proposed phonological pathways (e.g. how an initial velar nasal *ŋ might become g, k, h, or disappear), trace the semantic evolution from “breath” to “soul” to “self,” and survey evidence from diverse linguistic families. The tone is necessarily speculative—Proto-World reconstructions lie far beyond the traditional comparative method’s time horizon—but we aim to be authoritative in marshaling typological, phonosemantic, and cultural data that make this hypothesis intriguing. We also address methodological challenges and criticisms (such as coincidental convergence and the limits of regular sound laws at great time depths) while building a case that *ŋAN could be a genuine ancient lexical artifact: a linguistic fossil encoding the link between breath and personhood.

*Phonological Pathways of ŋAN and Its Global Reflexes#

One key pillar of this hypothesis is that the root *ŋAN underwent regular sound changes in different lineages, yielding a constellation of forms like an, ŋa, gan, kan, han, hun, jin, khwan, etc. We first examine how the initial consonant *ŋ (a velar nasal) might evolve in various language families, and then illustrate with examples:

*Retention or Loss of ŋ: Many languages do not permit *ŋ at the start of a word, leading either to its loss or modification. Thus, *ŋAN often survives as an- (with the nasal dropped) or with a compensatory glottal onset. For instance, in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) the initial ŋ is not reconstructible; the PIE root appears as *h₂an- or *an- (no initial nasal), meaning “to breathe”. This root gave Latin anima “breath, soul” and animus “mind, spirit”, Greek ánemos “wind”, Old Irish *anál/anadl “breath”, Gothic uz-anan “to exhale”, and even Old Irish animm “soul” – clear evidence that the an- form carried the notion of breath and soul in early Indo-European cultures. In these cases PIE *an- corresponds to the hypothesized *ŋAN with the ŋ dropped (or perhaps reflected as a lost laryngeal *h₂).

***ŋ > ŋ (Preservation): Some language families did preserve initial *ŋ. Notably, Proto-Sino-Tibetan is reconstructed with a first person pronoun *ŋa “I”. Old Chinese texts wrote “I” with characters like 吾 and 我, reconstructed as Old Chinese *ŋˤa and *ŋˤajʔ. Many modern Sinitic languages still retain traces of this: e.g. Cantonese ngo “I” (from *ŋo) and Shanghainese ŋu “I”. Tibetan as well uses ང (nga) for “I”, directly reflecting an ancient *ŋ. In these Sino-Tibetan examples, *ŋAN > ŋa (meaning “I”), which we argue is semantically connected to *ŋAN “soul, self” (see below for semantic shift). Likewise in the Austronesian family, Proto-Micronesian reconstructions include *ŋaanu or *ŋunu for “soul, spirit” (compare Mortlockese ŋéén “ghost, spirit” and Puluwatese ŋúún “soul” in Micronesia). These indicate *ŋ was retained into the protolanguage and only later changed in some daughters.

***ŋ > g or k (De-nasalization): Many languages turned an initial nasal into a stop. This often happens to *ŋ, yielding g (voiced velar stop) or k (voiceless). For example, some Tibeto-Burman languages have first person forms in k- alongside ŋ- forms, apparently due to a prefix or dialectal de-nasalization. In the Kiranti branch of Tibeto-Burman, Limbu has aŋa for “I,” but related Yamphu has ka for “I”, suggesting original *ŋa became *ga/*ka in some lines. Similarly, one hypothesis is that an early Indo-European dialect might have reintroduced a hard G/K sound: compare the Tocharian B first person singular pronoun āke (perhaps from *ŋa-ka) versus Sino-Tibetan *ŋa. While speculative, these hints show *ŋAN could surface as gan/kan. Indeed, the very Proto-World first person proposed by some is *anaku or *ŋaku—which contains both an *a(n)- element and a -ku, perhaps a pronominal suffix. If *ana- was the root “soul/self,” adding *-ku (“my”) could yield “my soul” as a way to say “I”. (Notably, the Akkadian word for “I” was anāku, and Proto-Semitic *ʔanāku > Arabic anā, Hebrew ani “I”, which scholars have long parsed as containing an *an- element.) This analysis implies that ŋAN > an (soul) could combine with a determiner (-ku or similar) to produce an “I” form that later fused. In any case, it is plausible that *ŋ > g/k occurred when nasality was lost but the place of articulation stayed velar, yielding g or hard c/k. We might see a faint echo of this in words like Latin genius (pronounced with a soft g [dʒ]), meaning a guardian spirit of a person or place. Genius is actually from PIE *genə- “to beget, produce,” not from *ane-, so it’s a separate root; but the conceptual overlap – genius as one’s spirit or “deity that generated you” – shows how a g-n sequence came to mean a personal spirit in Latin. It is tantalizing, if not probative, that genii/genie in folklore are spirits as well. (English “genie” for a spirit comes from French génie < Latin genius, yet was used to translate Arabic jinn – a nice convergence of form and meaning, discussed below.)

***ŋ > h (Fricativization) or ∅: Another common pathway is that *ŋ, especially if it had a preceding glottal element, could turn into a glottal fricative h. In some linguistic lineages, an initial velar nasal might have been reinterpreted as a nasalized glottal or a breathing sound, eventually heard as h or lost altogether. For example, Old Chinese 魂 *(hún) “soul” is reconstructed as m.qʷˤən or ɢʷən – here the root has a **q/**ɢ (uvular stop) with a nasal coloration ([m.] prefix) in Baxter–Sagart’s system, which in Middle Chinese became an *h- onset (MC hwon). Thus Old Chinese *ŋʷən might have shifted to *xwən > hwn > hun. In fact, Chinese 魂 hún “spiritual soul” closely resembles the Proto-Tai word for “soul”: Thai ขวัญ (khwan, with aspirated kh) means “animistic life essence; spirit”. Proto-Tai is reconstructed as *xwənA for this term, which is essentially the same sounds as Old Chinese *qʷən (if one ignores the minor prefixed element). Many scholars believe this is not coincidence: either one language borrowed from the other, or they both inherited the term from a common source. In either case, a velar→glottal shift occurred: Chinese *ɢw- > h-, Tai *ŋw- (or *qw-) > *xw- > kh-. The *ŋAN hypothesis sees this as a predictable transformation of *ŋAN: a nasal [ŋ] became a voiceless fricative [h/x] (a form of lenition), and perhaps the vowel *A lowered to *ɔ or *u in these words (giving *xwən with *ə or *un). Similarly, the Austronesian cognates show qaNiCu > anitu/hantu: Proto-Malayo-Polynesian qanitu (“ancestral spirit, ghost”) had an initial *q (glottal stop) plus a nasal consonant *N (which in Austronesian notation often stands for *ŋ). In many daughter languages, *q dropped or became *h, and *N became n: e.g. Tagalog anito “spirit, ghost” (from qa-niCu, losing the q-), and Malay hantu “ghost” (from qa-nitu, where q > h and nitu >ntu). The Polynesian cognate aitu/atua (spirit, god) similarly comes from *qanitu (glottal lost, *n retained). These show a pattern *ŋ/*q > ∅ or h. Even in the Indo-European sphere, there are parallels: the English word soul is unrelated (from Germanic *saiwalō), but the word ghost comes from PIE g̑hēis- “to breathe” – a different root, yet notably one that began with a breathy gh sound. And intriguingly, Egyptian ankh (written Ꜥnḫ), the ancient word for “life, soul,” begins with a glottal consonant (Ꜥ) and then nḫ, sounding like “anh.” Could Egyptian Ꜥnḫ be distantly connected to *ŋAN? We cannot say for sure, but it is striking that the word literally depicting life in hieroglyphs ("☥") contains an *an- sound.

***ŋ > palatal or y (palatalization): Though less common, a velar nasal in some environments might shift toward a palatal sound (especially before a front vowel). In certain languages, *ŋ > *ɲ (palatal nasal) > *y/j (approximant). If *ŋAN had a variant *ŋɛn or similar, it could, in theory, lead to a j- or dz- sound. This is speculative, but it offers one way to view the jin- type forms. For example, the Persian word jān (جان) meaning “life, soul, spirit” – often used as a term of endearment meaning “dear” or literally “my life” – is derived from Middle Persian gyān, from Old Persian jiiyān-, ultimately from Proto-Iranian *gʷyān- (“breath, life”). Proto-Iranian *gʷyān- in turn is linked to the same Indo-European root *an- “breathe” (with a prefix *gʷ- of unclear origin). In other words, Persian jan “soul” is an Indo-European reflex of *an- (with a *g/*j added), not a Proto-Sapiens borrowing – yet its sound (jan~djan) fits the *ŋAN pattern if we allow *ŋ > g > j. Now consider the Arabic jinn (جن) – the supernatural beings of Arabian lore. Arabic jinn (with /dʒ/ sound) comes from a Semitic root *√JNN meaning “to hide/conceal” (jinn are “invisible ones”), unrelated to “breath”. However, the resemblance to our hypothesized pattern is intriguing: jinn sounds like jin. It could be pure coincidence, but it is tempting to ask if an earlier substrate or convergence might be at play. Some long-range comparativists have indeed pointed out that Semitic ʔan(ā)– “I” (as in Hebrew ani, Arabic anā) and jinn “spirit” both echo the *an/*in pattern. We must be cautious here: formal linguistics does not derive Arabic jinn from *ŋAN. Still, from a phonosemantic perspective, cultures might have gravitated to similar sounds for the notion of spirit – perhaps a kind of sound symbolism or simply convergence. We include jin- mainly to complete the global constellation of lookalike forms, with the caveat that it may be convergent, not cognate.

To summarize these phonological pathways, Table 1 provides an overview of how *Proto-ŋAN might emerge in various guises:

*Table 1. Phonological Reflexes of ŋAN in Various Language Families

| Reflex Pattern | Example Languages | Form | Phonological Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| an- (Ø-initial) | Latin, Greek, Celtic (PIE reflexes) | anima (Lat. “soul”), anemos (Gk. “wind”), anadl (Old Irish “breath”) | Loss of initial ŋ (or *ŋ > h₂ > Ø); preserved vowel a |

| ŋa- (nasal retained) | Proto-Sino-Tibetan, Tibetan, Cantonese, Micronesian | ŋa (PST “I”), nga (Tib. “I”), ŋo (Cantonese “I”), ŋéén (Mortlockese “spirit”) | ŋ preserved as [ŋ]. Vowel A often retained as /a/ or fronted to /e/ in some (Mortlockese). |

| ga- / ka- (velar stop) | Kiranti (Yamphu, Waling), perhaps early IE dialects | ka (Yamphu “I”), aŋ-ka (Waling “I”); (Latin genius “spirit of person”, see text) | ŋ de-nasalized to [g] or devoiced to [k]; sometimes a fossilized *k- prefix (as in some Kiranti forms) |

| ha- / Ø- (aspiration or loss) | Chinese, Thai, Austronesian, Semitic? | hun (Old Chinese xwən “soul”), khwan (Thai “soul”), hantu (Malay “ghost”), anito (Tagalog “spirit”), (ani/ana in Hebrew/Arabic “I”) | ŋ > [h] via frication (Chinese, Malay) or > Ø (Tagalog, dropping Proto-Austronesian *q/*ʔ). Often a glottal stop or breathing replaces the nasal. |

| ja- / ɟa- (palatal/affricate) | Persian, Iranian, (Arabic) | jan (Persian “soul, life”), jān (Avestan “life”); (jinn (Arabic “spirit”) for sound analogy) | ŋ > gʲ > [ɟ] > [dʒ]/[ʒ] (palatalization yielding a j sound). Often accompanied by a following palatal glide or high front vowel (ŋA > ŋya). |

Note: The developments above are not monolithic sound laws but plausible tendencies observed in various families. For instance, ŋ > g occurred in some Tibeto-Burman languages, while ŋ > h is seen in Chinese and Malay. Each family’s regular sound laws would need to be demonstrated – the table simplifies a complex picture to highlight global patterns.

*From Breath to Soul to Self: Semantic Drift and the ŋAN Semantic Field#

If *ŋAN began as “breath, life-force,” how did it come to signify “soul”, “spirit”, “person,” or “I”? The semantic evolution posited is grounded in the near-universal animistic metaphor: breath is life. Cessation of breath signals death; conversely, many cultures conceive of an animating spirit as a kind of air or wind that inhabits the body. Thus the leap from “breath” to “spirit/soul” occurs independently in numerous traditions. We find abundant evidence of this semantic shift:

In Indo-European cultures, the link is explicit. The Latin animus and anima originally meant “breath” or “air” and by extension “spirit, soul, vital principle”. Greek pneúma (“breath”) similarly came to mean “spirit” or divine spirit, and Greek psychē meant “breath” before “soul”. Old Irish anál “breath” is cognate with animm “soul”. In Slavic, though a different root, Old Church Slavonic duchŭ (“spirit”) is from dūchъ (“breath”, cf. “to breathe” dýchati). These are all separate etymologies within Indo-European, but they illustrate a consistent metaphorical mapping: breath → life → soul. The PIE root *ane- “breathe” itself shows this mapping in the diversity of its reflexes: e.g. Sanskrit ánila means “wind” (physical breath of the world), while Sanskrit ātman – from a different root *ēt-men- (“to breathe”) – came to mean “soul, self” in the Upanishadic philosophical tradition. Notably, ātman literally meant “breath” or “spirit” and was used to denote the inner self or soul in Vedic philosophy, exactly paralleling the shift we propose for *ŋAN.

In Sino-Tibetan and East Asian contexts, breath and life are likewise linked. The Chinese concept of 氣 qì (archaic khiəp, modern qì) means “air, vapor” and by extension “vital energy”. While qì is a different root, Chinese hún 魂 and pò 魄 represented dual souls – the former more yang/spiritual, the latter more bodily – and tellingly, 招魂 (zhāo-hún “to beckon the hun-soul”) is a ritual of calling back the wandering breath-soul of an afflicted person. The term hún as we saw comes from Old Chinese m.qʷən and aligns with Thai/Tai khwan, both meaning a kind of life-soul that can leave the body. In Thai folk belief, one’s khwan is a personal life force that can be “lost” and must be ritually called back to ensure health. The fact that khwan and hun sound alike and share meaning suggests a deep-seated concept possibly inherited (or anciently borrowed) – exactly what the *ŋAN hypothesis predicts. Meanwhile, many Tibeto-Burman languages use words for “breath” or “wind” to mean “spirit.” For instance, in some Tibetan traditions the term rlung (wind) is used for life-energy, and in Burmese the word leik-pya (literally “wind”) can mean spirit or soul in folk tales. These parallels reinforce that the semantic leap from air to soul is a recurrent pattern. The Proto-*ŋAN word, meaning literally breath, would naturally acquire the sense of the invisible animating presence in a person.

The extension from “soul/spirit” to “person” or “human being” is also understandable. If *ŋAN meant the vital spirit or life-force in someone, it could easily come to stand synecdochically for the person themselves – especially in cultures where a person is essentially their spirit. In English we see vestiges of this: the word “spirit” can mean a ghost (disembodied person) but older usage also spoke of “a spirit” meaning a living person (“fine spirits we saw at the festival”). In many languages, the word for people or tribe is derived from a word for “breath” or “life”. For example, one hypothesized Old Norse term ándi “breath, spirit” (cognate with Icelandic andi) may be connected to the ethnonym Æsir (the gods) – though this is speculative, some have linked “Asu” (a Vedic word for spirit/life-force) to Aesir, implying “the spirits”. Whether or not that particular link holds, the general idea is that a group of people might call themselves “the living” or “the spirited ones.” Remarkably, the Proto-Austronesian qaNiCu (anitu) not only meant “spirit of the dead” but has cognates that mean “ancestor” or “old one” – blurring the line between spirit and person. In some Oceanic societies, anito/hanitu referred both to ancestral ghosts and to revered elders. We might imagine that *ŋAN in the distant past could similarly have referred to both the immaterial soul and, by extension, an ancestor or person imbued with life.

The final semantic leap is from “person” or “self” to pronoun. How does a word for soul/person become the word for “I”? There are plausible pathways attested in linguistic evolution. Pronouns often originate from emphatic self-designators (self, person, servant, child, etc., depending on culture). For instance, Thai first-person pronoun ข้า (khâ) originally means “servant/slave” (used humbly for “I”), whereas Japanese male ore (俺) literally meant “one’s self” or “one who is on one’s side”. If *ŋAN was an ancient noun for “soul/self”, it could have been used in phrases to mean “myself” or “this person here”. Over tens of millennia, such a usage could grammaticalize into a true pronoun. There is some evidence of this in comparative linguistics. In Semitic, the first person independent pronoun ʔanāku (Akkadian, Proto-Semitic) is sometimes thought to derive from a demonstrative or noun base ʔan-. One speculative breakdown is ʔanā-ku = “this (is) me” or perhaps “self + my (suffix)”, aligning with the earlier idea that *an/*ŋan meant self/soul. Similarly, the Dravidian first person singular nāṉ (Tamil), ñān (Malayalam), nānu (Kannada) might contain an element na- meaning self (though some reconstruct Dravidian *yan-/*nan- separately). It is striking that languages in completely different families have 1st person pronouns with an -n or nasal element: e.g., Tibetan nga, Chinese dialectal nga (for “I”), Burmese nga, Thai colloquial chan (from older ca-ŋan perhaps), Dravidian nan/ñan, Egyptian late-stage ink/ank (as in Coptic anok “I” – which starts with an), and more. This cannot all be coincidence; many linguists attribute it to the limited options for pronominal sound patterns and some chance (there are statistically common patterns like m-/n- pronouns). But the *ŋAN hypothesis suggests a deeper cause: these diverse “n” and “ŋ” first-person forms may all hark back to an ultracritical age when a word like *ŋan/*an meant “person/self.” In practical terms, an early human might have said something equivalent to “this soul” to mean themselves, pointing at their chest – and that phrase became fixed as the word for “I.” Indeed, one researcher gives the evocative example that ANAKU (Proto-Semitic “I”) could have literally meant “my soul”, illustrating how a possessed form of an(u) might yield a pronoun. Over time, as language became more abstract, the original meaning “breath” was forgotten in the pronominal use, surviving only in spiritual vocabulary.

Table 2 below sketches the major semantic shifts associated with the *ŋAN root, with examples:

*Table 2. Semantic Shifts from ŋAN (“breath, life”) in Various Traditions

| Stage / Meaning | Description | Examples of Reflexes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. “Breath, puff of air” | Literal breathing or wind, the act that signifies life | PIE ane- “to breathe” (Skt. an- in ániti “he breathes”); Latin animare “to give breath/life to”; Greek anemos “wind”; Yoruba mí “to breathe” (from which ẹ̀mí is derived). |

| 2. “Life-force, vitality” | The animating principle or vital energy that keeps one alive | Latin anima “breath, life, soul”; Sanskrit prāṇa “life-breath” (not from *an but analogous); Chinese 氣 qì “breath; life-energy”; Yoruba ẹ̀mí “breath, life, soul”. Many cultures conceive breath as life itself. |

| 3. “Soul, spirit (invisible self)” | The incorporeal essence of a person, often believed to leave the body in sleep or at death | Old Irish anim(m) “soul”; Latin animus “soul, spirit”; Old Church Slavonic duchu “spirit” (from “breath”); Chinese 魂 hún “soul”; Thai khwan “spirit, life essence”; Tagalog anito “ancestral spirit”; Malay hantu “ghost”; Mortlockese (Micronesia) ŋéén “ghost, spirit”; Yoruba ẹ̀mí “soul, spirit”. Also Arabic rūḥ “spirit” from “wind/breath” and Hebrew ruach “spirit, wind”. All these show breath = soul. |

| 4. “Person, human being” | A living person regarded as an animated being; sometimes a member of a group or tribe (“the people”) | Proto-Austronesian qaNiCu also applied to living elders (not just ghosts); Egyptian ankh “life” extended to mean “living person” (e.g., ni-ankh “the living”); possibly PIE ansu- “spirit” > Avestan ahu “lord” (a stretch). More concretely, Chinese rén (人, person) is OC niŋ, which is a different root but intriguingly close in form to *ŋan; Thai khon “person” (Proto-Tai ŋon, maybe from *ŋan?) and its likely cognate Lao kon suggest an earlier nasal *ŋ. It’s plausible that ŋan ~ ŋon meant “human being” in some lost Asian substrate. In English, “soul” can mean an individual (“50 souls perished”). |

| 5. “Self, identity (reflexive)” | The concept of oneself, often an internal sense of personhood or spirit | Sanskrit ātman “self, soul” (from “breath”); German Atmen “breathing” vs Atem “breath, spirit” gave philosophical das Selbst; Malay nyawa “soul, life” is also used for “self” in some idioms. We hypothesize *ŋAN in Proto-Sapiens filled this slot, referring to the essence of a person (hence “self”). |

| 6. “I” (first person reference) | Grammaticalization of the self-concept into a pronoun for the speaker. Often develops from words meaning “person” or “this one” or “servant” etc. | Proto-Sino-Tibetan ŋa “I” (perhaps from a noun “self”); Proto-Semitic ʔanāku “I” (contains ʔan- element, possibly “person”); Dravidian ñān/nāṉ “I”; Egyptian *ink/anok “I” (which starts with an-); English archaic “soul” used reflexively (“my soul is vexed” = “I am upset”). Yoruba emi “I” (emphatic pronoun) is literally ẹ̀mí “soul” used to mean “self”. Yoruba provides a crystal-clear case: emi means breath/spirit, and by extension it is the word for “I, myself” in the language. This is exactly the chain from breath to pronoun in one modern tongue. |

As Table 2 and the examples show, the journey from “breath” to “I” is long but traceable. Starting as the physical act of breathing, *ŋAN would become a term for the life-energy that breath conveys. Next, it would denote the soul or spirit – the invisible animating entity. From there, it could refer to a person’s essence or the person as a whole (especially in contrast to a corpse or in contexts like “so many souls survived the flood”). When used in a reflexive or emphatic way (“this soul right here”), it becomes a way to say “myself,” eventually grammaticalizing into a pronoun. Each step has robust cross-linguistic parallels, lending credence to the idea that a single primordial root could naturally undergo this semantic shift in different lines of descent.

It is also worth noting the mythological and cultural resonance of this continuity. Many creation myths involve a deity imparting life to humans by means of breath. In the Bible’s Genesis, God “breathed into [Adam’s] nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living soul” (Genesis 2:7). In Sumerian myth, the goddess Ninlil revives dead plants with her breath. The concept of life as breath is so fundamental that it would be astonishing if early human language didn’t have a word tying them together. If *ŋAN was that word, its preservation in the world’s linguistic diversity – however faded – would be unsurprising. Even in cultures separated by vast oceans and millennia, we find similar ideas: for example, among the Polynesians, there is the concept of ha, the breath of life (embodied in greetings like “aloha” – sharing the “ha”). In Hebrew, néshamah means breath and soul; in Hattic (an old Anatolian language), pšun reportedly meant both “breath” and “soul”. Such parallels may result from parallel evolution, but they set a fertile ground for a Proto-World seed.

Typological, Phonosemantic, and Cultural Correlations#

Beyond the raw linguistic evidence, a variety of typological and cultural data can be marshaled in support of the *ŋAN hypothesis:

Global Pronoun Patterns: It has long been noted that certain sounds recur in pronouns worldwide beyond chance. One well-known statistical tendency is the so-called “mama/tu” or M-T pattern (first person m, second person t) in Eurasia, and an N-M pattern (first person n/ŋ, second person m) in parts of the Americas. While these are statistical rather than absolute, they hint at deep time stability of pronominal sounds. The recurrence of n/ŋ for first person across distant families could be interpreted as the trace of an ancient *ŋa/*na first-person word. For example, languages in the Penutian and Hokan families of North America often have n for “I”, which Greenberg and Ruhlen saw as evidence of a deep N-M macro-family (“Amerind”). Whether or not those macro-families are valid, the pattern itself is real and invites explanation. The *ŋAN hypothesis provides one: perhaps the earliest speakers (before the global dispersion) used a word like *ŋan for “I/me”, and echoes of it remained in many daughter lineages unless later replaced. Not all families preserve it (Indo-European famously does not in the nominative “I”), but even Indo-European kept it in the oblique forms: the PIE accusative *(e)mé > “me” (m-form) but some argue PIE also had an emphatic first person *ana or *ono that survived in certain enclitics. It’s speculative, but it’s striking that when we look at unrelated languages – Yoruba emi, Tamil naan, Quechua ñuqa, Nahuatl nehuā, Ainu ani, Sumerian ĝe(en) (possibly in “ĝene” I) – a nasal vowel or consonant often appears in “I”. This could be merely because [n] is a simple sound that easily becomes a deictic marker. But phonosemantically, nasals have been linked to a speaker’s self (perhaps from the sound of hums, or because blowing air through the nose is a proprioceptive act). Deep comparative analysts like Bengtson & Ruhlen (1994) included a global etymology for **“I” as ʔANA or MI – intriguingly, ANA is exactly our root without the ŋ (they may have missed the ŋ). This convergence of pronoun typology and our proposed root is a key typological point.

Phonosemantics and Sound Symbolism: The *ŋAN hypothesis gains a bit of strength from the possibility that certain sounds are intrinsically associated with certain meanings across languages. Could a nasal+open vowel sequence be naturally associated with the self or soul? Some researchers of “phonosemantics” argue that nasals can convey internal, self-directed meanings (e.g., m, n often appear in words for “mother” or first person perhaps due to the mouth being closed, an inward position). While this is not a rigorous law, it’s suggestive that m and n are so common in words for me. Likewise, a vowel like /a/ (a low central vowel) is often used in demonstratives meaning “here/this” in many languages – perhaps because it’s a very basic, open sound. ŋAN consists of a nasal [ŋ] (with an [n]-like quality) and a low vowel [a] – phonetically, it’s a plausible primal syllable one might utter when patting one’s chest. It is not hard to imagine early humans referring to themselves or their vital breath with this simple syllable. Moreover, [ŋ] is a sound often associated with interiority since it’s a back nasal; some languages use it quasi-pragmatically (e.g., in some Bantu languages, nga can be a reflexive prefix). This is not firm evidence, but it provides a phonosemantic motivation for why *ŋAN might have “stuck” as a self/soul word.

Mythological Archetypes: Culturally, if *ŋAN was indeed an ancient word for soul or spirit, one might expect to find echoes of it in mythic names or religious concepts. Consider the following tantalizing correspondences: In many mythologies, the name of the first human or the first spirit is something like Anu/Anna/An. Sumerian mythology has “An” (or Anu in Akkadian) as the sky god – not directly “breath,” but as god of the heavens/air. Could the god An(u) be named from “sky” or from “spirit”? Some have speculated that Sumerian an (sky) could connect to the idea of breath/wind (the sky is the domain of winds and spirits). In Egyptian religion, the ankh sign (☥) is the key of life – its name ankh we discussed is “life” and maybe carries an echo of our root. Also, Egyptian myths speak of the “akh” – one of the souls of a person, the radiant one – possibly from a similar sound root. In the Norse Eddas, Odin’s gift to the first humans Ask and Embla included önd (old Norse “breath/spirit”). The Old Norse word önd (from *and/*andan, “breath”) is cognate to our *an- root via Proto-Germanic *andjan (cf. Gothic us-anan). We even see it in names: the name Andrew (Greek Andreas) comes from anēr “man” (perhaps originally meaning “breather”? that’s PIE *h₂ner-, different root meaning “man”, but interesting it sounds like an-). And the Persian epic’s hero Jamshid was also called Yima (from Yama), which in Avestan is related to yam “twin” not our root, yet Yima was associated with giving longevity and perhaps was called Jamshed “shine” not relevant. Still, across the world, the association of names starting in An-/On- with spirit or life recurs: Ani was an Egyptian personification of the mind, Anna in some Christian mysticism is linked to grace (though likely just “favor”). While these mythological notes are not proof, they paint a picture that something like ŋan/an was floating around in the deep cultural consciousness as a sound symbol for life and spirit. If the Proto-Sapiens community had such a word, its resonance might be why it was preserved even as language families diverged.

Clusters of Terms in Macrofamilies: The deep-comparison linguists often look for constellations of related meanings when positing a macrofamily root. In our case, if *ŋAN was Proto-World “soul/breath”, we might also expect related forms meaning “to breathe”, “nose” (organ of breath), or “to live”. Indeed, some hypotheses connect an- to words for nose (e.g., Proto-Austronesian anu “nose” has been posited, though others reconstruct *idu). In Dene-Caucasian proposals (which link Basque, Caucasian, Sino-Tibetan, etc.), there are roots like *HVN or *ʔAN for “to live” or “alive”. For instance, Basque has arnasa “breath” (where arnas- could be from an), and a word animu “soul, courage” (likely a Romance loan from animus but interesting nonetheless). In some Caucasian languages, the word for soul is am(w)- or han-. These could be coincidences or borrowings, but to a splitter-turned-lumper, they form a pattern. The *ŋAN model predicts that future research might uncover more such reflexes that were previously thought unrelated. For example, in the Nilo-Saharan family, the word nyàn in Dinka means “snake spirit” (perhaps unrelated, but *ŋan -> nyan is conceivable). In the Americas, Algonquian languages have Manitou (the great spirit) – intriguingly close to manitu/anitu (in fact, scholars think manitou < manitoo was an independent coining, but it’s a fun parallel that manitu in Cree means spirit and anitu in Tagalog means spirit). All these cross-connections highlight that breath = spirit = self might be a linguistic universal encoded in similar sounds across distant tongues.

In sum, typological patterns (like nasal-first-person pronouns), phonosemantic associations (nasal + “ah” for self), and common cultural metaphors (life as breath) all align with the proposed trajectory of *ŋAN. None of these is, on its own, definitive proof of a single origin – independent innovation is very plausible. However, the strength of the hypothesis lies in the convergence of evidence: linguistic forms from Eurasia, Africa, Oceania, and the Americas all pointing to a nasal-vowel root for soul/self, plus the near-universal metaphor that gives that root meaning. As one proponent put it, if such similarities occurred in just one or two regions, they could be chance, “but if we find the same group of consonants in tens of different language groups, for the same meaning, talking about chance is like talking about a meteorite falling from the sky and reshaping itself into a golden ring during that flight, repeatedly.” In other words, the global recurrence of *ŋAN-like words for spirit/person could well indicate a common ancestry rather than coincidental parallelism.

Deep Comparative Methodology and The Question of Regularity#

Proposing a “Proto-Sapiens” root requires stepping far outside the comfort zone of traditional historical linguistics. The comparative method as rigorously applied can confidently reconstruct protolanguages back perhaps ~6,000–10,000 years (e.g., Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Afroasiatic), but Proto-World would be on the order of 50,000–100,000 years ago – the time of the first Homo sapiens linguistic communities. Over such vast time spans, regular sound correspondences become extremely difficult to track. A major criticism of any global etymology (including *ŋAN) is the lack of established regular sound laws linking the languages in question. Indeed, mainstream linguists argue that without systematic sound correspondences, look-alike words mean little – human languages have relatively few basic phonetic shapes, so some overlap is expected by chance. The *ŋAN hypothesis must face this head-on:

Convergence vs. Cognate: Could it be that many languages independently chose a similar sound for “soul” simply because of the natural connection between nasal sounds and humming (breathing) or due to onomatopoeia (perhaps imitating the humming of breath)? This is possible. We know onomatopoeia and symbolic sound can lead to similar words (e.g., mama for mother globally). However, breathing is a rather quiet sound – a soft exhale isn’t as onomatopoetic as, say, cough or achoo. If anything, a panting sound huh might be imitated, but ŋan is not an obvious onomatopoeia. The breadth of distribution of *ŋAN-like terms and the specific tying of meaning (breath/spirit) makes pure convergence less likely than in the case of, say, mama/papa. As one rejoinder to the convergence argument, Ruhlen and colleagues note that while any one or two similarities could be coincidence, seeing the same root in dozens of languages on all continents for the same concept greatly strains the chance hypothesis. Statistically, the odds of random convergence diminish exponentially as you add more groups to the comparison (provided the comparisons are independent). Our table includes Indo-European, Afroasiatic, Sino-Tibetan, Austronesian, Niger-Congo (Yoruba), possibly others all showing *an ~ ŋan for spirit/I. The probability of all these aligning by chance (with meaning alignment) is arguably small. Still, critics retort that given thousands of languages and limited phonemes, some overlaps will occur globally – and we as pattern-finders might be cherry-picking those that fit our narrative. This is a valid caution. We must ensure we are not just selecting data that support *ŋAN and ignoring counterexamples (for instance, many languages have totally different words for soul or I that share no resemblance).

Lack of Regular Sound Correspondences: Another criticism is that even if *ŋAN words are widespread, the sounds don’t match via regular laws. Indo-European anima vs. Sino-Tibetan ŋa vs. Austronesian anitu vs. Semitic anā — yes, they all have *an or *na, but to a skeptic this is too loose. In real genetic relationships, we expect systematic correspondences (e.g., Proto-Nostratic proposals attempt to align PIE *n = Afroasiatic *n = Dravidian *ṇ, etc., in a rule-governed way). Our hypothesis spans such time that many intermediate stages are lost; we leap from Proto-Sapiens to modern languages without reconstructed intermediates (aside from known protofamilies). This is admittedly a weak point if one demands classical proof. The *ŋAN hypothesis cannot (at present) demonstrate a neat regular chain of changes from 100k years ago to today. Instead, it relies on mass comparison of many languages for a similar form-meaning pairing, an approach pioneered by Joseph Greenberg. Greenberg’s multilateral comparison eschews rigorous sound laws at first, looking instead for global patterns, and only then tries to discern correspondence patterns. Critics like Lyle Campbell and Donald Ringe have argued that without enforced regularity, one can mistakenly group unrelated languages by accidental similarities – the infamous “pizza coincidence” (the fact that pizza means “pie” in Italian and piirakka means “pie” in Finnish is coincidence, not evidence of relation). Could *ŋAN be a pizza coincidence on a grand scale? For balance, we acknowledge that many mainstream linguists remain unconvinced by Proto-World etymologies precisely because they lack tightly knit sound laws. For example, Indo-European p might correspond to Semitic f in a systematic way in Nostratic, but what is the systematic relationship of IE *n- to Chinese *h- (as in anima vs hun)? At first glance, none – but that’s because these families have been diverging for so long that intermediate steps (and thus intermediate regular shifts) have been lost. Proponents argue that if you had all the intermediate proto-languages, you could stepwise account for the changes (indeed, one can imagine Proto-East-Asian had *ŋ- for soul, which Chinese turned to *h-; Proto-Nostratic had *ħan for breath, which became *an in IE, *ʔan in Afroasiatic, etc.). But those reconstructions are hypothetical. So, this hypothesis inevitably operates at a level where the criterion of regular sound change is relaxed. This is controversial, but not entirely without method: researchers try to group languages into higher-order families (e.g., Nostratic, Dené–Caucasian, Austric) and apply the comparative method within those macro-families first. If *ŋAN can be shown in several of these macrofamilies, that strengthens the case that it predates them. For instance, *an is in Indo-European and Afroasiatic (Nostratic?), and *ŋa in Sino-Tibetan and Na-Dene (Dené–Caucasian?), and *an in Austronesian and Austroasiatic (Austric?) – if each macrofamily yields a cognate set, then by transitivity *ŋAN might have been in Proto-World. Critics counter that those macrofamilies themselves are unproven, so it’s a bit of circular reasoning.

Time Depth and Erosion: Even with the best will, reconstructing a single word over ~300 generations of languages (assuming ~1,000 years per generation of language change) is incredibly ambitious. Sound changes, semantic shifts, borrowings, and replacements would have muddied the waters. Many linguists believe that secure reconstruction probably cannot go beyond ~10,000 years because eventually all phonological patterns get scrambled. However, there is an opposing view that certain ultraconserved words or roots might survive far longer. For example, some have claimed words like tik for “finger/one” or akwa for “water” appear globally in many families (Ruhlen even listed 27 global etymologies). If those claims hold any water, *ŋAN “breath” might be another ultraconserved word – arguably one even more essential to early humans than “water” or “stone”, because identifying living beings (breathers) and conceptualizing the life within could have been fundamental. It’s also possible that *ŋAN survived not continuously in each lineage, but was recreated or preserved through contact. For instance, if one ancient group had *ŋAN and another had a different word for soul, but through cultural exchange (intermarriage, ritual sharing) one term became widespread, it could explain how the term crossed family boundaries. The idea of an ancient Wanderwort (wander-word) that spread with early modern humans is not crazy – consider that boom (for the sound) is similar across languages, or some early tool names might have spread. If *ŋAN was part of an early spiritual or religious vocabulary, migrating tribes might have borrowed it from each other, thus seeding it in many lineages. This complicates the genetic picture (it wouldn’t be a straight inheritance, but it would still be an extremely old word in human usage).

Counterexamples and Negative Evidence: To truly test the hypothesis, one should look at languages where it doesn’t hold. Are there major families where words for breath/spirit/I have completely unrelated forms? Yes, plenty: e.g., the Turkic word for soul is tın (Old Turkic tın “breath, soul” gave modern Turkish can, interestingly pronounced jan in Turkic – which does match our pattern!). Japanese has tamashii (soul) and watashi (I), nothing like *an. Dravidian “soul” is not clearly *an (Tamil uses uyir “life” for soul, unrelated). Bantu languages use -moyi or -pɛpɛ for breath (e.g., Lingala mɔ́í “soul”, Swahili roho from Arabic) – not *an, though interestingly some have mu-ntu “person” where -ntu might be from a root *-tu (not *an). It might be that *ŋAN was lost or replaced in many places, which is expected over such time. But if, say, Austronesian had an independent word for soul (like *qaQaR or something) with no *n, that weakens the claim. In Austronesian we do have other soul words like kalag (Visayan kalag “soul”) etc., so qanitu was just one of multiple terms. The global picture is messy, so one could argue we’re focusing on those cases that fit and ignoring those that don’t. A rigorous approach would require a statistical test: do words meaning “breath/life/soul/I” have sounds like N-A-N more often than would be expected by random chance across the world’s languages? If yes, that might indicate a genetic or functional cause. If no, then we may be seeing patterns in noise.

We acknowledge these challenges and criticisms not to undermine the hypothesis but to clarify that it is highly ambitious and not yet widely accepted by linguists. The *Proto-World hypothesis remains outside the mainstream, and many experts doubt whether we will ever have enough evidence to prove a single origin for all languages. The *ŋAN root is proposed within this speculative enterprise. As such, the arguments for it are cumulative and interdisciplinary rather than strictly linguistic. We lean on cultural universals and broad typologies in a way that classical historical linguists find unpersuasive. For instance, pointing out that breath = life in many cultures is interesting, but it doesn’t prove those words share an ancestor – it could just be parallel metaphor. We must be careful, therefore, in claiming too much. The *ŋAN hypothesis should be seen as a model or narrative that organizes a set of cross-cultural linguistic facts in a coherent way, which could indicate a common origin, but which certainly needs more research and evidence (especially intermediate reconstructions and consideration of alternative explanations).

Criticisms and a Stronger Model#

Let us summarize the key criticisms and our responses, to paint a balanced yet favorable picture of the *ŋAN model:

Criticism 1: “Chance resemblance on a small syllable.” Detractors point out that *ŋAN is a CVC syllable with very common sounds. Nearly every language has an /n/ or /ŋ/ and an /a/ vowel. With thousands of concepts and limited phonemes, it’s inevitable some unrelated words will coincide. Response: We concede that an ~ na could easily arise independently. However, the specificity of meaning across our sample is notable. We’re not comparing arbitrary words like “fish” and “star” – we’re consistently looking at words for vital breath, soul, or self. If random, we’d expect no particular semantic clustering of similar forms across families. The fact that “breath/life” and “soul/person” so often have an nasal+vowel base tilts the odds away from pure coincidence (especially given multiple independent examples in each continent). Additionally, some of the forms (with ŋ, or with specific clusters like *nt or *nd in derivatives) are less trivial phonetically than just “na”. The Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *qanitu has a specific shape, as does Proto-Sino-Tibetan *ŋa. The alignment of those cannot be fully explained by chance. So while chance can’t be ruled out, it seems insufficient as an explanation for the full range of data.

Criticism 2: “No regular sound laws, just loose comparison – pseudo-science!” Traditionalists argue that mass comparison without sound laws is not rigorous; one can “find” evidence for any hypothesized root by cherry-picking. Indeed, earlier “global etymology” attempts were criticized for precisely that reason. Response: We acknowledge that our evidence is not of the same nature as, say, the correspondence of Latin p to Greek ph to Sanskrit p in PIE *p-… It’s a different scale of comparison. However, we have tried to incorporate regular sound change insights where available. For instance, we noted that Proto-Tai *xwən and Old Chinese *qʷən line up well, fitting known patterns of Chinese-Tai contact or common ancestry. We also noted that within Sino-Tibetan, *ŋa → *a or *ka is a documented pattern. Within Indo-European, *h₂enh₁ -> *an and sometimes *ne (perhaps in negation or pronouns) is known. So if we break the problem into smaller macro-family chunks, we can apply the comparative method to each: e.g., reconstruct *ŋVn in Proto-Kra-Dai and *ŋʷən in Old Chinese and see if those could come from a common ancestor around 4000 years ago – some scholars like Laurent Sagart have indeed posited an Austro-Tai connection where words like *khwan (Tai) and *hun (Chinese) share a common origin. That is a regular sound law scenario (Chinese *m-qʷən vs Tai *xwən). Similarly, in Nostratic studies, an *an- for “breathe” has been compared: Illich-Svitych reconstructed Nostratic *ʔănćV (“breath/spirit”), which would yield Afroasiatic *nafš- (as in Hebrew nefesh “soul, breath”) and IE *ans- (putative, though IE actually has *ane-). Thus, we are attempting to work within smaller correspondences and then aggregate. It’s just that the ultimate aggregation (Proto-World) is beyond normal reach, so we have to rely on patterns. We also emphasize that regularity might still be there but at a deeper level: perhaps *ŋAN had variants like *ʔAN or *HAN that led to different outcomes. If we found consistent rules (e.g., initial ŋ in Proto-World became glottal stop in Afroasiatic, *h in Sino-Tibetan, zero in Indo-European), that would strengthen the case. Currently, those correspondences are hypothetical but not implausible: For instance, glottal stop and *h are the reflexes of Proto-Afroasiatic laryngeals in many daughter languages (Egyptian Ꜥnḫ begins with Ꜥ which could correspond to a Proto-Afroasiatic glottal stop if *ʔan(a)ḫ was “to live”). And PIE *h₂ (a laryngeal) might itself reflect an earlier ŋ or ʕ. Some bold Nostraticists have suggested PIE *h₂en “breathe” comes from Afroasiatic *ʕan (with a pharyngeal) – thus a potential regular link of Proto-World *ŋ/ʕ to these. This is speculative, but not outlandish. In short, while we lack a fully worked-out sound law matrix, we are not entirely ignoring regularity; rather we see tantalizing proto-phonemes aligning (e.g., a nasal or laryngeal at the start, an /a/ vowel) across lineages, which is the first step toward a systematic correspondence.

Criticism 3: “Time depth is too great – language does not permit reconstruction that far.” Many linguists, perhaps the majority, believe that after perhaps 8,000–10,000 years, lexical evidence is too eroded to be reliable for reconstruction. After 100,000 years, it’s argued, essentially all vocabulary would be replaced or transformed beyond recognition. Response: This conservative view has been challenged by some recent studies suggesting a small core of ultra-stable words. For instance, research by Pagel et al. (2013) found a set of words (including pronouns, numerals, kin terms) that change slower than others, potentially retained across families beyond 10k years. Pronouns in particular are known to be sticky (e.g., the English “I” is directly from PIE *eg(h)om, surviving ~6000+ years). It’s not unthinkable that “I” or “soul” could last 20,000 years in some lineages. If multiple such lineages later meet (e.g., through the Out-of-Africa exit), they might share ancient retentions. We also consider that humans 100k years ago had fully modern cognitive capacities and likely similar basic needs in language – words for family, body parts, natural environment, and existential concepts like life and death. If any words were preserved, those might be. The word for fire or water might get innovated often, but maybe the word for breath – being less often taboo or replaced – persisted. Admittedly, 100k years is a long stretch. But as an analogy, some genes or myths trace back that far; why not a word? The Hokule’a argument (the navigation by stars across the Pacific) shows that even oral cultures can preserve surprisingly old knowledge (Polynesians carried oral histories across 50 generations). Language, being dynamic, won’t preserve everything, but certain root morphemes (especially short ones that can be reattached to new grammar) might survive. *ŋAN could have persisted in baby talk, ritual chants, or names of deities, even if everyday language shifted around it. In essence, we treat the extreme time depth not as a barrier but as a challenge requiring interdisciplinary evidence (hence our use of cultural and myth data). It’s a hypothesis that stretches conventional limits – we fully admit that – but it’s framed in a way that is at least consistent with human cultural continuity (e.g., the concept of soul is arguably as old as humanity, so a word for it might be too).

In addressing these criticisms, we refine the *ŋAN hypothesis into a stronger model: one that is not merely “look, these words sound similar,” but one that integrates regular change at intermediate levels, explains why this particular root would be conserved (due to its fundamental meaning and possibly sound symbolism), and remains open to modification as new data emerge. We are effectively proposing *ŋAN as a working reconstruction for a semantic core rather than a final proven fact. The model predicts that further research in historical linguistics, genetic anthropology, and cognitive science might uncover supporting evidence – or could refute it by finding counterexamples that can’t be explained. Either outcome will deepen our understanding of how language encodes the most basic human experiences.

Conclusion: The Breath of Life as a Linguistic Fossil#

We have journeyed from a single syllable in a hypothetical deep past – *ŋAN – to a vast network of words and ideas in the present. The core hypothesis is that *ŋAN was not just a word, but an idea encoded in a word: the idea that breath is life, life is spirit, and spirit is the essence of personhood. Through regular phonological transformations (nasals becoming stops or disappearing, vowels shifting, etc.) and through natural extensions of meaning (metaphor and metonymy from “breath” to “soul” to “self”), this primordial sign has arguably left discernible traces in languages around the world. We identified likely *ŋAN reflexes in Indo-European (*an- in anima, anil-, etc.), in Sino-Tibetan (ŋa “I”, Chinese hun), in Austronesian (qanitu > anitu/hantu), in Afro-Asiatic (perhaps Egyptian ankh, Semitic anā “I”), in Niger-Congo (Yoruba emi), and beyond. We constructed tables of sound changes and semantic shifts which, while necessarily simplified, illustrate a plausible pathway for each step. We also discussed the methodological controversies – acknowledging that not all linguists will accept these connections as proven.

Crucially, we tried to show why this particular root would be so special as to endure: it sits at the heart of human self-awareness (breathing is the first and last sign of life; knowing oneself as a breathing being may have been key in the emergence of consciousness). It is poetic to think that whenever we say “I am” we might be unconsciously echoing the breaths of our distant ancestors who first spoke of their inner essence. The *ŋAN hypothesis, speculative as it is, offers a compelling narrative: that a single syllable uttered in the Paleolithic dark, perhaps as a man exhaled on a cold night and realized that the invisible mist leaving his mouth was “him”, has continued to resonate in our languages to this day. It encodes the continuity between the corporeal act of breathing and the intangible sense of self – a continuity that early mythmakers and shamans around the world understood and passed down.

In presenting this hypothesis, we painted a “strong” version of the model – one that presumes a real genetic (common origin) relationship. Even if that strong version remains unproven, the exercise is fruitful. It highlights patterns in global languages that any theory of language origin must account for: Why do so many languages link breath and soul? Why do so many first-person pronouns begin with nasals? Why do words like anima, anito, ani (I), nga (I), hún, khwan, jan cluster around a small set of sounds? A uniformitarian view (independent development under similar human experiences) can answer part of that. A monogenetic view (single origin) can answer another part. Reality might be a mix: perhaps an ancestral word *ŋAN existed and some languages kept it, while others reinvented it later because the concept demanded that sound. Our hypothesis is an attempt to merge those views, suggesting that the concept was so salient that the original label hung on tenaciously, and even when lost, new languages tended to reinvent a similar-sounding word by analogy.

The ultimate test of the *ŋAN hypothesis will be in future research: as more ancient DNA gives clues to migration, as more proto-languages are reconstructed and compared, will the pattern hold and be explainable via intermediate forms? We envision, for instance, finding that Proto-Nostratic had *ʔăn(V) for “soul/breath,” Proto-Austric had *qanay, and that both came from a common *ŋan. Or discovering ancient inscriptions or loanwords that tie two far-flung instances together (imagine a scenario where a Neolithic ceremonial chant is found preserved, using a word like *ngan for spirit, cropping up in both Asia and Africa). These are dreams, but not impossible ones.

Even as a speculative framework, the *Proto-Sapiens *ŋAN hypothesis serves an important function: it reminds us that behind the cacophony of world languages, there may lie faint echoes of a time when our ancestors shared not only genes and tools, but words – words for the most profound elements of their existence. “Breath, spirit, life, self” – these were surely among the first preoccupations of thinking humans. It is satisfying to think that a single vocal gesture, *ŋAN, might have encapsulated all those notions and survived in various guises to be spoken today. When a Cantonese speaker says ngo (我) for “I”, and a Yoruba speaker says emi (ẹmi) for “I” or “spirit”, and a Thai mother coos about her baby’s khwan, and an old Russian folktale speaks of the zhivat’ (living) soul, perhaps unbeknownst to them they are all iterating pieces of an ur-word that once meant “the living breath within.”

In conclusion, while the Proto-Sapiens *ŋAN hypothesis remains unproven, it is a compelling model that ties together evidence from historical linguistics, semantics, and anthropology into a coherent story: that *ŋAN was an ancient word for the breath of life, and through regular sound change (ŋ > g/k/h/∅) and semantic broadening (breath → soul → person → pronoun), its legacy can be seen in a global constellation of words for spirit and self. It’s a grand and adventurous hypothesis – one that invites both excitement and healthy skepticism. As we have shown, there are strong patterns and parallels supporting it, even as there are logical critiques to be addressed. By continuing to refine the phonological correspondences and by searching for more “fossil” words in under-documented languages, we can further test this hypothesis. And regardless of the final verdict, exploring *ŋAN deepens our appreciation of how intimately language, thought, and culture are interwoven – from the first breath we take to the first word we utter, and perhaps, to the very first word our species collectively spoke.

Sources: Evidence and examples have been drawn from a broad survey of linguistic research, including Indo-European etymological sources, Sino-Tibetan reconstructions, Austronesian comparative data, and ethnolinguistic studies of concepts of soul. These illustrate both the widespread reflexes of the proposed root and the cultural concepts attached to them. Critics’ perspectives on deep reconstruction and chance convergence have also been noted, ensuring that the argument remains balanced and grounded in known linguistic principles. The hypothesis remains a work in progress – an invitation to further inquiry rather than a finished proof – but one that stands on a foundation of fascinating linguistic coincidences that just might be more than coincidences.

FAQ#

*Q1. What is the ŋAN hypothesis?

A. It’s a speculative linguistic theory proposing that an ancient Proto-Sapiens word, *ŋAN, meant “breath” or “soul” and is the ancestor of similar-sounding words for spirit and self across global language families.

Q2. How could a word survive for over 15,000 years?

A. The hypothesis suggests that certain “ultra-conserved” words, especially those for fundamental concepts like “soul” or “I,” can resist replacement and survive through millennia of language change.

Q3. What is the main evidence for this theory?

A. The evidence is a “constellation” of similar-sounding words in unrelated language families (e.g., PIE *an-, Sino-Tibetan *ŋa, Austronesian *qanitu) all relating to breath, spirit, or self, which suggests a shared origin rather than coincidence.

Q4. Why is this hypothesis not accepted by mainstream linguistics?

A. Mainstream historical linguistics relies on regular sound correspondences, which are extremely difficult to establish over such vast time depths. The theory is considered highly speculative and outside the bounds of the traditional comparative method.

Sources#

- Ruhlen, Merritt (1994). On the Origin of Languages: Studies in Linguistic Taxonomy. Stanford University Press.

- Bengtson, John D. & Ruhlen, Merritt (1994). “Global Etymologies.” In On the Origin of Languages.

- Pagel, Mark, et al. (2013). “Ultraconserved words point to deep language ancestry across Eurasia.” PNAS 110(21): 8471-8476.

- Watkins, Calvert (2000). The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots. Houghton Mifflin.

- Baxter, William H. & Sagart, Laurent (2014). Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction. Oxford University Press.

- Blust, Robert & Trussel, Stephen (2010). Austronesian Comparative Dictionary. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- Campbell, Lyle (2013). Historical Linguistics: An Introduction. MIT Press. [For a critique of deep reconstruction]

- Dixon, R.M.W. (1997). The Rise and Fall of Languages. Cambridge University Press. [For discussion on time depth limitations]