TL;DR

- Eden’s “forbidden fruit” marks the first spark of recursive self-awareness—an upward Fall into reflection.

- John reframes Genesis: Logos (meaning) predates matter, making consciousness the cosmos’s ground, not its by product.

- Axial-Age thinkers (Heraclitus, Upanishads, Laozi) converge on one substrate—Logos/Tao/Brahman—once minds can grasp abstractions.

- Gnostic sects flip the story: the Edenic serpent is Christ-as liberator, the demiurge is the jailer; knowledge saves.

- Dying-and-rising gods (Odin, Osiris, Christ) ritualize the trauma of awakening: ego death buys wisdom, reenacted in initiation rites.

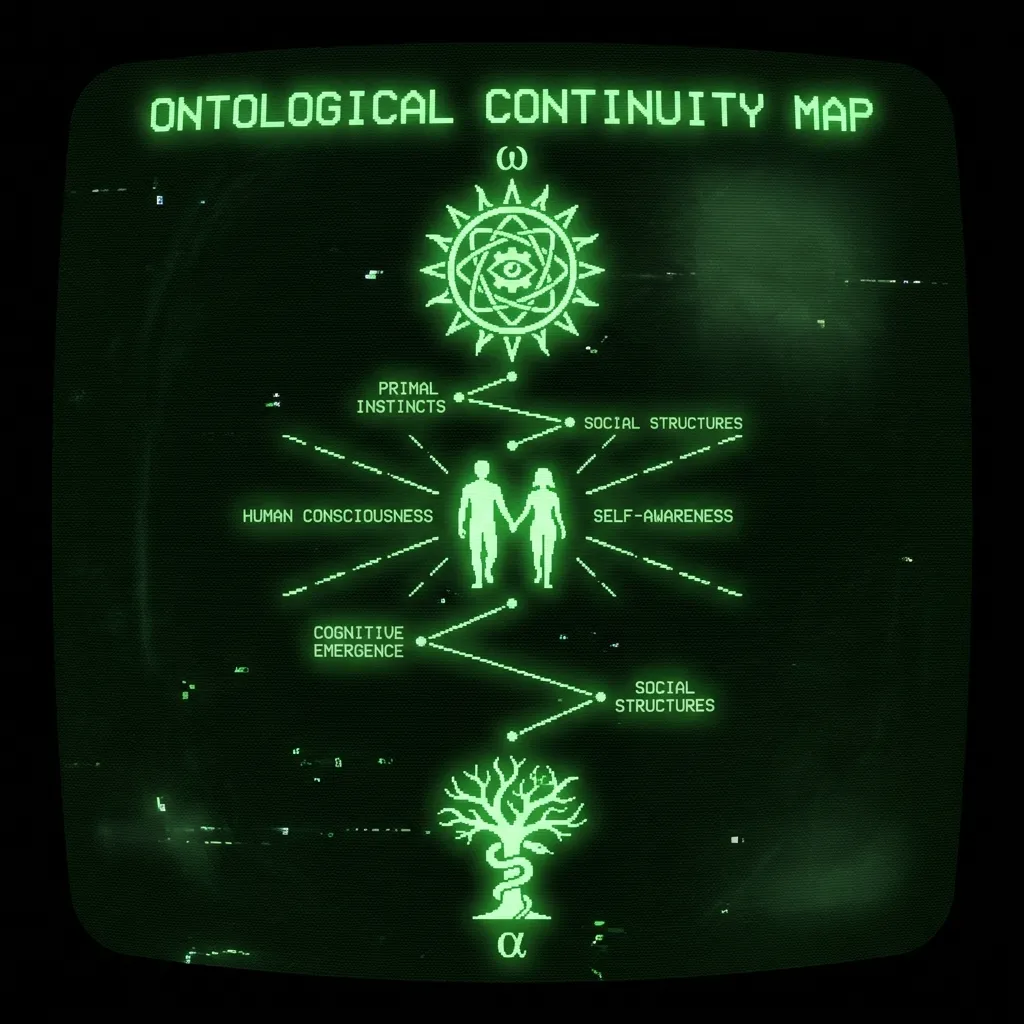

Introduction: From Eden to Self and Beyond#

In the vast timeline of human development, there may be no greater inflection point than the emergence of self-reflective consciousness – the ability to think about our own thoughts. The Eve Theory of Consciousness (EToC) posits that this capability arose relatively recently in our prehistory and left profound echoes in mythology and philosophy. This theory builds on earlier ideas like Julian Jaynes’s famous hypothesis of the late origin of introspection. Jaynes argued that as late as the Bronze Age, humans “knew not what they did” – they lacked a subjective inner mind and instead obeyed hallucinated voices of gods, as in the Homeric epics. In Jaynes’s view, true introspective ego-consciousness only crystallized around the end of the second millennium BCE. EToC agrees that consciousness (in the full modern sense of an introspective ego) developed rather than being biologically inevitable from the start, but it ventures that this “great awakening” occurred much earlier – roughly at the end of the last Ice Age, during the transition to the Holocene (circa 10,000 BCE). Crucially, EToC suggests that this transformation was first achieved by women (hence “Eve Theory”) and then culturally transmitted to men through powerful, even traumatic, initiation rites. In this telling, the legendary Garden of Eden story encodes a real psychological revolution: the dawning of self-awareness in our species and the bittersweet knowledge it brought.

This long-form essay will explore how such a reading of human consciousness evolution illuminates key mythological and philosophical developments. We will examine Genesis 1–3 (the Creation and Fall) as a cultural memory of humanity’s first steps into reflexive self-consciousness. We will then turn to the opening of the Gospel of John, “In the beginning was the Logos…,” as a philosophical reframing of Genesis that makes mind and meaning the root of reality rather than mere matter. This leads to the idea – central to EToC – that Logos (cosmic “Word” or reason) is not just human cognition but the very metaphysical substrate of being, which became intelligible to us as our minds developed the capacity for abstract self-reflection during the Axial Age. Next, we’ll trace how heterodox religious movements like the Gnostics (e.g. Naassenes, Ophites) and Manichaeans recast the Eden narrative: to them, the serpent was not a villain but a liberator bringing divine knowledge, even an analog of Christ or “Lucifer” the light-bringer. This startling inversion underscores a theme that the awakening of the inner self – gnosis or knowledge of one’s true mind – was seen by some as a sacred, not sinful, event. Finally, we will consider the possibility that extremely ancient shamanic rituals – for instance, the motif of the “hanged god” who suffers to gain wisdom – symbolically preserve the trauma of early self-awareness. Such rites may be the deep ancestor of myths of dying-and-rising deities, including the ultimate crucifixion story at the heart of Christianity. Throughout, our goal is to weave rigorous analysis with a narrative thread, showing how the emergence of consciousness can be read in our oldest stories. The tone will be rationalist (in the spirit of Slate Star Codex-style curiosity), yet appreciative of metaphysical and symbolic nuance, treating myths neither as literal history nor as mere fantasy but as encoded insights into the evolving human psyche.

Eden’s Dawn: Genesis as the Birth of Self-Reflective Consciousness#

Few myths are as resonant as Genesis 3, the story of Adam and Eve, the forbidden fruit, and the expulsion from Eden. In the traditional theological reading, this is the Fall of Man – a lamentable lapse that introduced sin and death into the world. The Eve Theory of Consciousness invites a very different interpretation: what if the Eden story isn’t about a fall from perfection at all, but rather a rise to a new level of awareness? On this view, Genesis encodes our species’ “fall” into self-consciousness – a fall upward, so to speak, into the mental world of reflection, selfhood, and moral knowledge. Before this event, early humans lived much as other animals: they were likely aware in the sense of having perceptions and feelings, but they did not possess the recursive awareness of awareness that we consider the hallmark of the modern mind. In the language of Genesis, they “were naked and were not ashamed” (Gen. 2:25) – that is, they experienced the world and themselves innocently, without second-order thoughts or any concept of ego. After eating from the Tree of Knowledge, “the eyes of both of them were opened” (Gen. 3:7). The serpent’s enigmatic promise – “when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Gen. 3:5) – suddenly makes sense in this psychological interpretation. Their eyes were already open in a literal sense; what changed was the mind’s eye. Adam and Eve acquired the ability to step outside themselves and reflect – to judge good and evil, to imagine alternate possibilities, and crucially, to see themselves as selves. In doing so, they indeed became “like gods” in the sense of gaining creative agency (through imagination) and moral knowledge – a point even the sympathetic serpent affirms: “your eyes will be opened… you will be like God”.

This “opening of eyes” can be understood as the moment of recursive self-awareness. Philosopher Bernardo Kastrup describes it as the ability to “stand outside our own thoughts… to contemplate our situation as if looking at ourselves from the outside. This capacity… called self-reflective awareness… is essential for making sense of nature”. It was a double-edged sword. On one hand, it gifted early humans with unprecedented cognitive power – the ability to plan, to question, to invent, to analyze. Genesis symbolizes this with the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, implying a broad spectrum of understanding was unlocked. On the other hand, self-reflection brought a heavy burden of suffering previously unknown. The Genesis text poignantly notes that the first thing Adam and Eve do post fruit is feel shame at their nakedness, covering themselves. In psychological terms, they acquired the capacity for self-conscious emotions like shame, guilt, and pride. They also likely acquired existential anxiety: a knowledge of mortality and future consequences. As EToC argues, animals do not dread their eventual death – “lions do not envision their demise as they lay sated,” but a “sapient being” can project forward and fear the inevitable. In Eden, God warns that on the day they eat the fruit “you shall surely die” – a prophecy not literally fulfilled that day, but in a deeper sense Adam and Eve’s carefree ignorance died and they became mortals in mind, aware that death awaited them. Thus, paradise was lost not because a moral rule was broken per se, but because the childlike innocence of an unselfaware psyche was irretrievably broken. Humanity left the seamless unity of nature (walking naked without thought) and entered a state of alienation – “separated from nature and from God,” as the EToC puts it. In other words, the “Fall” was the birth of the introspective self, a traumatic yet transformative crossing of a threshold.

EToC even suggests a concrete scenario for this event. It hypothesizes that toward the end of the last Ice Age (the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, when our ancestors were forming the first settled communities), some individuals – plausibly women – first tasted self-knowledge, to use the Edenic metaphor. Perhaps through a fortuitous confluence of biological readiness and cultural stimulus (one might speculate about language complexity, symbolic art, or even psychedelic plants), these first “Eves” achieved a reflective insight: they heard not just the voices of gods or instincts in their heads, but recognized an internal voice as their own Self. Seeing that this new awareness was powerful (“seeing it was desirable,” as Genesis says of the fruit), they then initiated others. Early cultural artifacts hint at mysterious initiation rites in prehistoric times, and EToC theorizes that women deliberately taught men self-awareness through intense rituals – “mind-rending rites of passage,” involving ordeals of sensory deprivation, fear, or pain to jolt the psyche into a self-observing state. Such rites would be the origin of the many mythic narratives in which knowledge is gained through suffering. Notably, after this initiation, “Man henceforth lived separated from nature and from god” – a direct parallel to Adam and Eve being expelled from the Garden into a world of toil, sweat, and thorns. The “consciousness meme” (as EToC calls it) spread like wildfire once invented, quickly conferring survival advantages (planning, communication, social complexity). Over millennia it became universal among Homo sapiens, and even our biology adapted – genes favoring higher introspective and linguistic capacity were selected for, so that now every normal human child recapitulates this acquisition of selfhood early in life, essentially trivially, as our neural development and cultural upbringing automatically induce self-awareness in toddlerhood.

Reading Genesis 3 as a hazy cultural memory of these events casts its symbols in a fascinating new light. The serpent becomes, not a mere tempter, but a catalyst of evolution – the trigger for humanity’s leap into a larger mind. The Tree of Knowledge represents the brain’s newfound ability to distinguish opposites (good and evil, self and other) and thus to conceptualize and judge. The Garden symbolizes the pre-conscious state of animal unity with nature – an innocence that is blissful but ignorant. When God says, “Behold, the man has become like one of Us, knowing good and evil” (Gen 3:22), it reflects a begrudging acknowledgement that humans had acquired a godlike faculty – the imago Dei (image of God) within was activated to a new degree. Yet this awakens divine concern: a self-aware being is powerful and could “also take from the tree of life” (perhaps a metaphor for mastering life’s secrets or achieving immortality), so the human is cast out, to prevent further immediate godlike upgrades. In psychological terms, once self-awareness arose, evolutionary and cultural forces ensured we could not go back to innocent ignorance; we had to develop within the harsh realities of the world, gradually growing into our godlike potential. As one interpreter put it, “God knew what He was doing – after all, who put that tree (and that serpent) in the Garden?”. In other words, the myth itself hints that this leap was part of the natural (or divine) plan for humanity. The Eden narrative, then, is the story of humanity waking up – a bittersweet awakening to be sure, bringing toil, pain, and death into conscious view, but also bringing the first glimmer of moral freedom and rational thought. It’s our species’ oldest story because it represents the birth of the storyteller: the moment the human mind could finally observe itself and begin to narrate its place in the cosmos.

The Logos in the Beginning: John’s Gospel and the Ontology of Creation#

If Genesis encodes the dawn of human self-consciousness in mythic allegory, the Gospel of John’s prologue might be seen as encoding the next great development: the realization that mind and meaning underlie the cosmos itself. John opens his Gospel with a deliberate echo of Genesis 1: “In the beginning…” – but instead of “God created the heavens and the earth,” John writes, “In the beginning was the Logos (Word), and the Logos was with God, and the Logos was God” (John 1:1). This is a profound shift in emphasis. Rather than a chronological account of material creation (light, sky, land, etc.), John presents creation as an ontological and cognitive event: the primordial fact is not matter or even a deity as an actor, but Logos – meaning, logic, reason, word. “All things were made through the Logos,” he continues, “and without it nothing was made that has been made” (John 1:3). In essence, reality is spoken into being, and the Word is divine. This can be read as a philosophical reinterpretation of Genesis’s creation story, framing it not in terms of a temporal beginning but in terms of an eternal principle of intelligibility. It’s as if John is saying: behind the events of creation described in Genesis lies an ultimate ground – the mind of God, the rational structure that gives the universe coherence. Creation, in this view, is not just a one-time act of magic, but an ongoing participation in the Logos that is both with God and is God. This was a radical melding of Hebrew theology with Greek philosophy.

John’s concept of the Logos drew upon a rich tradition. In Hellenistic thought, ever since Heraclitus (6th century BCE), logos had meant the rational order of the cosmos – an “unseen force, timeless and truthful,” an account (word) that “regulates and runs the universe”. Heraclitus had cryptically declared, “Listening not to me but to the Logos, it is wise to acknowledge that all things are one” – implying a unity behind apparent diversity, accessible to the intellect. Later, the Stoic philosophers identified the Logos with the fiery divine reason pervading all things, and even spoke of the logos spermatikos, the seminal reason that shapes life. In Jewish thought, there was a parallel idea in the figure of Wisdom (Sophia) or the Word of God. The Hebrew Bible speaks of God creating by word (“And God said, ‘Let there be light’…” in Genesis 1). Hellenistic Jewish philosophers like Philo of Alexandria (1st century BCE) explicitly connected these concepts, describing the Logos as the “Thought of God” or the divine reason that intermediates between the transcendent God and the material world. By the time the author of John’s Gospel was writing (late 1st century CE), the term Logos was ripe with connotations from both Greek and Jewish contexts: it meant the principle of cosmic order and also the divine Word through which creation comes into being. John’s genius was to personify this abstract principle in the figure of Christ: “the Logos became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). Thus, the Christian message framed Jesus not just as a moral teacher or messiah, but as Logos incarnate – the literal embodiment of the mind of God.

Setting aside the specifically Christian claim about Jesus, what is crucial for our purposes is how John reframes “Genesis in the beginning” as the beginning of meaning. The true genesis of the world, in John’s prologue, is the eternal existence of Logos. This implies that intelligibility precedes materiality. Reality at its core is rational or word-like. We might call this an idealist or ontological interpretation of creation. It resonates strongly with the idea from the Eve Theory that Logos is “the metaphysical substrate made intelligible.” Indeed, one can interpret “In the beginning was the Logos” to mean that the foundation of existence is a cosmic intellect or sense – a sort of cosmic consciousness – and that all physical things emanate from this. Intriguingly, EToC suggests that if its narrative is correct, quotes like John 1:1 are “memories from the moment it became possible to imagine the future… a missive from when our world was cut from the cloth of language”. In other words, when the human mind attained reflection and language, it created a new world of possibilities (the world of thought, story, and prediction). John’s declaration that “what has come into being in the Logos was life, and that life was the light of men” (John 1:3-4) beautifully ties creation to cognition: life (especially human life) is lit up by the Logos. We could say the universe becomes self-aware through the human mind, and John’s prologue can be read as alluding to that: the light (of Logos) shines in the darkness, and finally the darkness “did not overcome it” (John 1:5). By phrasing creation in terms of Word and Light, John elevates it to the realm of ideas and insight. Creation is not merely a material act by a distant deity; it is an ongoing cognitive event – the continuous shining of intelligibility into the void, the perpetual giving of form (Logos) to chaos. It’s a philosophical creation story befitting a culture that had begun to seriously reflect on ontology and epistemology.

We can see John’s prologue, then, as a kind of bridge between myth and philosophy. It takes the mythic language of Genesis (“in the beginning”) and weds it to the philosophical concept of Logos. For a moment, imagine how a newly self-aware culture might reinterpret its own origin: rather than simply retelling the old myth of a garden and a talking snake (which by John’s time many educated people probably saw as allegory at best), they articulate the origin in abstract terms – “In the beginning was Meaning.” This is a bold assertion that the universe has an intelligible origin and character. It’s almost a declaration of cosmic rationality: the cosmos is not a senseless accident, but rooted in Logos/Word, implying that our human capacity for reason taps into the very foundation of reality. In effect, John 1:1 reframes creation as the emergence of order and reason, which for a rationalist reader is a deeply satisfying convergence of theology with a kind of metaphysical proto-science. The Eve Theory of Consciousness adds another layer: perhaps this very idea of Logos-as substrate only became “thinkable” during the Axial Age, when human thought became sufficiently abstract and reflexive. Let’s explore that next – how in the middle of the first millennium BCE, across different civilizations, human minds discovered higher-order abstractions (like Logos) and became aware of themselves as part of a universal Being.

The Axial Age: When Mind Becomes Aware of the Metaphysical Substrate#

The Axial Age – a term coined by philosopher Karl Jaspers – refers to the remarkable era roughly between 800 BCE and 200 BCE when a wave of transformative philosophies and religions sprang up independently in several regions: Greek philosophy, Hebrew prophecy, Zoroastrianism in Persia, Buddhism and Hindu Upanishadic thought in India, Taoism and Confucianism in China. Jaspers and many since have argued that during this period “man becomes conscious of Being as a whole, of himself and his limitations” confronts the depth of existence and asks fundamental questions. Prior to this, even after the initial advent of self-awareness, humans largely navigated the world through myth, custom, and uncritical belief. But in the Axial Age, there was a palpable shift toward second-order thinking: people began to reflect on reflection itself, to criticize their own thoughts, to seek universal truths. This was essentially a maturation of the reflective capacity – a new level of self-consciousness that enabled abstract concepts like “Truth,” “One God,” “Nirvana,” or “Tao” to take center stage. Scholars point out that self-reflection and analytical reasoning blossomed in this age, supplanting the purely narrative/mythic cognition of earlier times. It’s as if the mental mirror got polished to a high shine: not only could humans think about their thoughts, they could now think about the ground of thought itself, and the ground of being. The result was an explosion of intellectual and spiritual development that still defines what it means to be “modern” humans in many respects.

One hallmark of Axial Age thought is the discovery of universal principles behind reality. We see this vividly in the concept of the Logos in Greek thought. Heraclitus, around 500 BCE, was one of the first to use the term in a transcendent sense, asserting that there is a common Logos, an objective logic to the cosmos, which most people fail to grasp. He implied that our individual minds are fragments of or participants in that larger rational structure – “Thinking is shared by all,” he said, cautioning that those who act as if they have a private mind apart from the Logos are living in illusion. In a similar timeframe, the Upanishads in India (c. 800–500 BCE) were teaching that the essence of the self (Atman) is identical to the essence of the cosmos (Brahman) – “that art thou,” as the Chandogya Upanishad famously puts it. This is arguably another way to speak of Logos: Brahman is the metaphysical substrate of all existence, an absolute reality or cosmic spirit, and the enlightened insight was that our own consciousness is a mode of that infinite consciousness. Meanwhile in China, Laozi’s Tao Te Ching (perhaps 6th–4th century BCE) talked about the Tao, the Way underlying heaven and earth, an ineffable source that can be intuited but not fully expressed – “the Tao that can be spoken is not the constant Tao.” Yet, conceptually, Tao is akin to Logos (indeed some scholars have explicitly compared the two). It is the natural order and principle that if followed leads to harmony. Even in the Middle East, Israel’s prophets and sages were moving from a tribal, interventionist God to a more universal and introspective concept of deity. In books like Job and Ecclesiastes (post-500 BCE), we see profound reflections on the human condition, and in Hellenistic Jewish texts like the Wisdom of Solomon or Philo’s writings, Wisdom/Logos is elevated as a pre-existent force through which God creates and sustains the world.

What ties all these threads together is a newfound capacity for abstraction and self-critical thought. The Axial Age mind could step back not just from immediate perceptions, but from its own culturally given narratives, and ask: What is the truth behind these appearances? What is the ultimate reality? This required a high level of metacognition – essentially, the mind thinking about thought and being in the most general sense. The Eve Theory suggests that this was the period when the Logos became intelligible to the mind: that is, humans could finally conceive of something like a universal principle or metaphysical substrate and articulate it. Prior to that, even though humans after the “Eden moment” were self-aware and capable of reasoning, their thought was largely mythopoetic – carried in concrete stories and personifications. The Axial Age represents a great demythologizing (at least among intellectual elites of the time) and a turn to logos in the sense of rational discourse. It’s telling that the word “logos” itself, before meaning cosmic principle, simply meant “word” or rational argument. In Greek philosophy, the move from mythos to logos was essentially the move from explaining the world through narratives about personified gods to explaining it through impersonal principles and logical reasoning. Heraclitus again is emblematic: he critiqued the popular religion and posited an abstract, hidden harmony (the Logos) that only the wise discern. Similarly, in Buddhism, Siddhartha Gautama replaced the traditional Vedic creation myths and sacrificial system with an analysis of consciousness and suffering, and a method (the Eightfold Path) to achieve liberation – a very different kind of spiritual project grounded in introspective insight. All these developments indicate that by the mid-1st millennium BCE, humans were reflecting on consciousness itself and on the eternal structures within which consciousness finds itself.

In this light, John’s proclamation “In the beginning was the Logos” can be seen as a culmination of Axial Age insight. It is a statement one could not imagine appearing in, say, the Epic of Gilgamesh or in Homer. Those earlier texts, as rich as they are, do not step outside themselves to posit a single unifying principle of reality – they are still within the world of narrative and particular gods. By John’s era (1st century CE), the concept of Logos had been refined over centuries of Greek thought, and the Jewish theological concept of the divine Word/Wisdom had likewise matured. The author of John stands on the shoulders of both traditions and essentially equates the two: the Hellenic Logos is identified with the Hebrew God (and then with Christ). This move only makes sense in a world where educated minds have absorbed the Axial Age revolution in thinking: an era that can appreciate an abstract, ontological creation account. Indeed, Jaspers noted that people living after the Axial Age “more closely resemble the peoples of today” in their mental framework, whereas those before it “lacked much self-reflection” and lived in a world where truths were accepted mythically without question. The Axial Age gave us the habit of questioning and seeking universal answers – Who are we? What is the cosmos? How should we live? – questions that simply weren’t articulated explicitly before. And in various ways, the answers often converged on the idea that behind the chaos of life there is a cosmic order or mind. The Greek kosmos itself means order. Anaxagoras spoke of Nous (Mind) that set the cosmos in motion, Plato spoke of the Form of the Good (a perfect abstract principle) illuminating reality like the sun, the Stoics spoke of the Logos penetrating and binding all things, and the Jewish sages personified Wisdom as “a breath of the power of God, a pure emanation of the glory of the Almighty… She orders all things well” (Wisdom of Solomon 7:25-29).

In short, by reflecting on its own processes, the human mind in the Axial Age came to perceive a reflection of itself in the cosmos. Just as a self-aware mind finds an “I” behind its thoughts, these philosophies found a single source or essence behind the phenomena. This was the discernment of the metaphysical substrate – call it Logos, Brahman, Tao, or God – that connects our inner world with the outer world. The theory proposed here—that Logos is not merely human thought but the metaphysical substrate itself, only comprehensible once minds evolved enough, dovetails with this historical development. The Logos was always there, one might say, but only when humans attained a certain level of abstraction could they name it and recognize its role. It’s notable that many Axial Age texts emphasize that the ultimate reality is difficult to perceive, often requiring discipline or revelation. For example, Heraclitus says men are “unable to understand” the Logos even after hearing it, and Laozi says most people miss the Tao. This hints that the realization of a metaphysical substrate was a breakthrough attained by relatively few “wise” – analogous to how not everyone immediately grasped self-consciousness in EToC’s early scenario. But once it was formulated, it spread and became part of the collective understanding, allowing later thinkers like John to confidently declare the Logos as fundamental. Today, we take for granted concepts like “the universe follows laws” or “there are universal truths” – all echoes of that Axial leap when our ancestors’ mental gaze lifted from local tribal concerns to the endless heavens and the depths of the soul. Thus, the Axial Age can be seen as the coming-of-age of human consciousness, when it not only knows itself (the Fall/Eden moment) but knows the world’s ground through itself.

Gnostic Light: The Serpent as Liberator and the Inversion of the Fall#

Even as mainstream Judeo-Christian tradition came to regard the Fall as the origin of sin and the Logos as identified with Christ, there were undercurrents of religious thought that re-read the Eden story in a dramatically different light. These were the various Gnostic sects of late antiquity, as well as the dualistic religion of Manichaeism (3rd century CE), which drew on Gnostic ideas. To the Gnostics, knowledge (gnōsis) was the path to salvation – not faith or obedience. So naturally, they looked at the story of Adam and Eve and asked: why is the acquisition of knowledge depicted as a bad thing? Why would a true God deny humans the knowledge of good and evil? These questions led them to an audacious reinterpretation: what if the serpent was actually the good guy? What if the serpent in Eden was an agent of a higher, benevolent God, trying to free Adam and Eve from the ignorance imposed by the Creator? This flips the script: the Eden story becomes not the fall of man, but the beginning of man’s enlightenment, hampered only by a jealous lesser deity. Gnostic myths accordingly often villainize the Creator (identified with the demiurge Yaldabaoth) and valorize the serpent or Sophia (Wisdom) who prompted Eve to seek knowledge. The early Church fathers, who wrote against the Gnostics, attest to these interpretations with a mix of horror and grudging detail. For example, Irenaeus in the 2nd century describes certain Gnostic groups who taught that “the serpent in paradise was wisdom itself (Sophia)” and that by eating the fruit, Adam and Eve received true knowledge from the higher God. These groups (sometimes called Ophites from ophis, Greek for snake, or Naassenes from naas, Hebrew for snake) even worshipped the serpent symbolically, seeing it as the emblem of divine wisdom and the liberator of mankind.

The Ophites and related sects took elements of the Hebrew Bible and gave them radical “counter-readings.” They identified biblical villains or outcasts – Cain, Esau, the Sodomites, even Judas Iscariot – as heroes or instruments of the true God, insofar as those figures rebelled against or defied the ignorant Creator. Meanwhile, the righteous figures favored by the Old Testament (like Jacob or Moses) were sometimes viewed as dupes or servants of the false god, and thus less enlightened. In these myths, the serpent in Eden is sometimes equated with Christ or at least with a Christ-like revealer. One group interpreted the brazen serpent Moses lifted up in the wilderness (Numbers 21:9) – which the Gospel of John also uses as a type for the Crucifixion (John 3:14) – as proof that the serpent is a saving power and that Jesus himself “recognized” and aligned with the serpent’s cause. They noted that Jesus advised his followers to be “wise as serpents” (Matthew 10:16) and sometimes even called the pre-Christian savior figure who came to Eden the serpent of light. Indeed, in some Gnostic texts from Nag Hammadi, Christ is portrayed as a luminous epiphany that either appears in Eden or in the world to undo the work of the demiurge. For instance, The Hypostasis of the Archons (a Gnostic tractate) presents the spiritual Eve and the higher spirit as assisting the serpent to awaken Adam and Eve, much to the archons’ dismay. The basic message: the “Fall” was actually humanity’s first step toward gnosis, and it was assisted by a beneficent entity symbolized by a serpent. Far from being the source of evil, this event was the seed of liberation, unjustly castigated by the world’s false rulers. It’s not hard to see how this aligns with the Eve Theory’s positive take on the rise of self-awareness. The Gnostics, in their mythic language, were essentially saying that becoming self-aware and morally knowledgeable was a blessing, not a curse – it came from Wisdom (Sophia) and leads us back to the true God beyond this flawed world.

What about the ominous figure of Lucifer? In mainstream Christian lore, Lucifer (the fallen “Light-Bearer”) became conflated with Satan and the Eden serpent. But intriguingly, the term lucifer (Latin for “morning star, light-bringer”) can have a dual interpretation. Some later esoteric Christian and Gnostic-influenced writers played on this and dared to regard Lucifer in a positive sense – as a symbol of enlightenment. While actual Gnostics of the early centuries didn’t use the Latin name Lucifer , the concept of a light-bringing figure who rebels against an unjust authority fits their narrative perfectly. In essence, their serpent is a Luciferian figure (in the original meaning of light-bringer): one who brings divine light (knowledge) into the world. A few Gnostic sects did merge Christ and the serpent symbolically – for example, the Naassene Sermons talked about the “snake” as a representation of the higher Christ and the need to “be wise as serpents.” The Manichaeans – a later dualist religion founded by the prophet Mani – inherited many Gnostic themes and taught a cosmic struggle between Light and Darkness. In Manichaean myth, the world is a mixture of light and dark, and salvation comes through liberating the light. They syncretically identified figures from various traditions with this struggle. It appears that Mani considered the biblical God (Jehovah) to be a lower power and the serpent’s promise of knowledge to be aligned with the forces of Light. Manichaean texts speak of Jesus as Illuminator and often use language of illumination and enlightenment, consistent with viewing the acquisition of knowledge (even if via a serpent) as a holy act. St. Augustine, a former Manichaean, later recounted that the Manichaeans blasphemously “honored” the serpent for opening Adam’s eyes. In effect, Gnostics and Manichaeans performed a bold mythic inversion: Eden was the beginning of salvation, not damnation. The true fall, in their eyes, was the entrapment of the human soul in ignorance and matter, which the serpent’s intervention began to undo. Jesus, in some Gnostic interpretations, is thus the same voice as the serpent – the continuance of that mission of enlightenment, now appearing in another form to finish the job of teaching humanity the truth and freeing them from the counterfeit god’s tyranny. It is no accident that some medieval heretics (like the Cathars) explicitly linked Lucifer and Christ as identical or saw the Eden snake as Christ in disguise – ideas that got them condemned, but which show the persistence of this counter-tradition.

For a rational modern reader, what do we make of these wild reinterpretations? At minimum, they highlight an important insight: knowledge and self-awareness were equated with divinity by these sects. Rather than longing to return to unconscious paradise, the Gnostics celebrated the awakening of mind as the first step on a journey back to a higher Paradise of spirit. This is a striking parallel to the Eve Theory’s framing of self-awareness as both traumatic and transcendent. To the Gnostics, the pain and toil that came with the Fall were justified by the fact that humanity could now strive for gnosis – a chance to reconnect with God on a higher level (not as ignorant pets in a garden, but as enlightened sons and daughters of the true God). The serpent, in their mythology, is essentially the bringer of metacognition – the one who says, “Hey, become aware, open your eyes, see yourselves.” In Gnostic poetry, the roles are reversed: the Creator who forbade knowledge is the deceiver, and the Serpent who encouraged it is the revealer. This mythic inversion serves to affirm the value of consciousness. It suggests that deep down, even orthodox Christian theology (with its Logos doctrine) could not fully suppress the notion that knowledge is divine – after all, the Gospel of John calls Christ “the true light that enlightens every man” (John 1:9). The Gnostics just took it one step further and applied it back to the beginning: the light that enlightens man first shone in Eden via a serpent. In a way, the Gnostics reclaimed the serpent as a symbol of humanity’s inner spark of divinity – the very Nous or Mind that distinguishes us. Their audacity got them labeled heretics, but their ideas continue to intrigue, not least because they present an ancient endorsement of the view that the awakening of the self-aware mind is the moment of liberation, not corruption. This stands as a powerful mythic testimony aligning with the Eve Theory’s positive spin on the origin of consciousness: that initial awakening was humanity’s first salvation, the first step toward reunion with the Source (the Logos or true God), even if orthodox mythology remembered it as a fall from grace.

Rites of Passage: The Hanged God and the Cross – Trauma as Transformative#

If the Gnostics encoded the value of awakening in myth, the Paleolithic and ancient rituals of humanity may encode the experience of awakening – particularly its traumatic, death-and-rebirth character. EToC speculates that when the first “Eves” initiated the first “Adams” into self-consciousness, it likely involved ordeals that were terrifying and transformative. It’s reasonable to assume that spontaneously attaining reflective consciousness could be a shock – a sort of existential crisis. To suddenly “become as gods knowing good and evil” is to suddenly see oneself from the outside, to feel profoundly vulnerable (hence the immediate shame and hiding in the Eden story), and to realize the inevitability of death. Such a psychic upheaval might well have been experienced as a death of one identity and the birth of another – the death of the innocent, unconscious self and the birth of the doubting, self-aware ego. Anthropologists have noted that many traditional initiation rites mirror the pattern of symbolic death and rebirth: the novice is put through extreme trials (isolation, pain, intoxication, scarring, etc.), experiences dissolution of their former self, and then is “reborn” as a new person (an adult member of society, often with a new name). This pattern may be more than just a social formality; it could stem from the deep memory of the actual first awakenings of consciousness in our distant past. In other words, initiation ceremonies may ritually re-enact the original awakening event so that each new generation, especially the young men in many cultures, can acquire the self-reflective “mind” that was once gained through great struggle. EToC highlights “mind-rending rites of passage” in which men were initiated by women into sapience. While direct evidence from 10,000+ years ago is scant, later mythology preserves suggestive motifs of just such ordeals.

One of the most arresting of these motifs is the Hanged God. The Norse myth of Odin is a prime example. In the Hávamál, Odin recounts how he sacrificed himself to himself by hanging on the world-tree Yggdrasil for nine nights, wounded by a spear, fasting from food and drink, in order to obtain the knowledge of the runes (symbols of wisdom). He literally dies a shamanic death on the tree and emerges with mystical insight. The parallels to the Christian story of Jesus on the cross are striking – so striking that scholars and comparative mythologists have often commented on them. Odin is suspended on the cosmic Tree of Life; Jesus is crucified on a wooden cross (often poetically likened to a tree). Odin is pierced by a spear; Jesus is lanced in the side by a spear. Odin cries out and grabs the runes (knowledge) as he falls from the tree, achieving wisdom for the world; Jesus, according to Christian belief, accomplishes the redemption (spiritual knowledge of salvation) for the world through his death. Both even refuse worldly comforts – Odin gets no bread or mead, Jesus refuses the gall-mixed wine offered to dull his pain. These similarities are unlikely to be historical borrowing (the Norse myths were written down much later, but the oral traditions could be very old). Rather, they hint that both stories tap into an ancient archetype: the sacrificial ordeal of the wise one. It’s the pattern where enlightenment (or salvation) is attained through extreme suffering and a form of death.

This archetype probably originates in shamanic practices. In many shamanic cultures, an aspiring shaman undergoes a crisis – dreams of dismemberment, visions of being boiled or hung or taken apart by spirits – and then comes back together as a healer with new sight. The “hanged man” as an image of initiation even survives in the Tarot deck (the Hanged Man card, depicting a figure hanging upside down, often interpreted as surrender and new perspective). We can surmise that as the first humans were forced into introspection (perhaps through life-threatening stress or intense rituals), they experienced a kind of ego-death. To the outside observer, it might have looked like they went mad or were possessed, then recovered as a different person – much as an initiate is “possessed” by spirits and then returns as a shaman. These experiences would have been encoded in mythic terms available to the culture. For a hunting society, the image might be being hung on a tree (a fate reserved for sacrifices or traitors, thus symbolically a big deal) and then acquiring wisdom (the prize). The tree itself is a potent symbol – a link between heaven, earth, and underworld; in Eden, the Tree of Knowledge stands at the center. The Norse cosmic tree with Odin and the Edenic tree with the serpent and ultimately Christ’s cross (often called the tree in Christian hymnody) all resonate with each other. It’s as if the axis mundi (cosmic axis) is the stage for this transformative sacrifice.

Now, when Christianity appeared and spread, it framed Jesus’s crucifixion as a unique historical event – the Son of God sacrificed for mankind. But one reason the crucifixion mythos had such profound resonance (beyond doctrine) is arguably because it tapped this deep structure of the sacrificial redeemer. Early European converts, for example, could recognize something of Odin in Christ – indeed, medieval art from Scandinavia depicts Christ hanging on a cross entwined with branches, explicitly merging the two images. Theologian and mythographer C.S. Lewis once remarked that Christianity is a myth become fact – implying that it took the archetypal myth of the dying god and claimed it happened in history. Whether one views it theologically or anthropologically, the point remains: the crucifixion recapitulates the pattern of death-to-ego and rebirth-to-spirit. Christ suffers, dies, and rises immortal – thus believers symbolically die to their old self (in baptism, “crucified with Christ”) and are reborn in a higher life. This is essentially the same pattern as the initiations or the Odin myth, just cast on a cosmic scale.

From the standpoint of the evolution of consciousness, we might say that myth and ritual remembered that to become fully conscious, something must die. Perhaps it is the naive self or the childlike reliance on external authority (voices of gods, parent-figures, etc.) that must die for the inner self to be born. The Paleolithic initiatory ordeals were a way to induce this, and stories like Odin’s sacrifice or Inanna’s descent to the underworld, or the dismemberment of Osiris in Egyptian lore, are narrative cousins of the same meta-myth: knowledge has a price; awakening can feel like death. It’s telling that even in Genesis, after Adam and Eve gain knowledge, they eventually do die (just much later) – mortality is the price tag. But mythologically, one can experience a kind of death before physical death – that is the whole premise of initiation. Thus, when we speak of “traumatic experiences of metacognitive awakening ritually remembered,” we refer to this idea that the first awakening was so earth-shattering that its memory needed to be re-enacted and culturally integrated through ritual drama.

Consider also the possibility of entheogenic or psychedelic rituals in prehistory – some have speculated that ingesting psychoactive plants (the forbidden fruit?) could catalyze self-transcendence or self-awareness, but also scare one to death. The “wounded healer” motif in shamanism (only by facing insanity or death can you heal others) might reflect a literal psychological trial early humans went through as their brains and cultures experimented with consciousness. Over time these were codified into rites and myths so that the process could be controlled and repeated. By the time of recorded antiquity, we have the Mystery religions (like the Eleusinian Mysteries in Greece) where initiates underwent secret rituals that simulated death and rebirth, often with a promise of spiritual illumination. We don’t know the details (they were, well, mysterious and secret), but participants like Plato hinted that they “experienced things terrifying and wonderful” and came away with a conviction in the immortality of the soul – essentially a gnosis. Again, we see that pattern: ordeal, near-death experience, then enlightenment. Christianity in its own way made a public Mystery: through identification with Christ’s Passion (suffering, death, resurrection) the believer attains salvation (a form of enlightenment or eternal life). It is as if all these streams – from the Stone Age shaman, to Odin on the tree, to the mystic initiate, to Christ on Golgotha – are iterations of a core human insight: to ascend to a higher plane of mind or spirit, one must pass through a crucible of self-negation.

The Eve Theory suggests that the crucifixion myths are ritual memories of the first consciousness-awakening. When the first humans gained self-awareness, it was like a lightning bolt splitting the psyche; later generations sanctified that moment as the sacrifice of a god. Perhaps those first initiators (the proverbial “Eves”) were deified or remembered as divine figures who gave up something precious to enlighten humanity. There is a hint of this in the myth of Prometheus as well – he suffered (chained to a rock, his liver eaten daily by an eagle) for giving fire (symbol of knowledge) to humans. Prometheus is essentially a Luciferian figure (in fact the morning star Lucifer was associated with Prometheus in some traditions), another “light-bringer” god who is punished for helping mankind advance. We see the overlaps: serpent = Prometheus = Lucifer = Odin = Christ in their roles as bringers of knowledge or salvation through self-sacrifice. It’s as if different cultures took the primordial initiation event and cast different characters in the role – sometimes a trickster serpent, sometimes a titan, sometimes the supreme God himself – but always with the theme that humanity’s higher consciousness was acquired through a courageous (and painful) act of sacrifice.

So, by the time we reach the common era, the mythic counter-reading of the Eden story by Gnostics, and the widespread trope of the sacrificial savior, together affirm that what orthodox religion called the Fall and Redemption can be understood in psychological terms as the Awakening and its Integration. The Fall/Awakening gave us our minds and moral knowledge; the Redemption/Integration (whether through Christ or through gnosis or enlightenment) promises to resolve the alienation that ensued, reconnecting us with the ground of being (Logos/Brahman) but now fully conscious. In ritual terms, one had to undergo a personal crucifixion (symbolically) to attain that integration – to transcend the ego that was born in Eden and realize the higher Self. This is the mystical thread that runs through a lot of Axial Age religion and later esoteric traditions.

Conclusion: Mythology as the Mirror of Mind’s Evolution#

We began with a simple but far-reaching proposition: the evolution of human consciousness – especially the emergence of self-reflective awareness – is recorded in our greatest myths and philosophical narratives. Having traversed from Eden to the Logos, from Gnostic serpents to hanged gods, we can now appreciate how coherent that story can be. In this synthesis, Genesis 1–3 is not primitive nonsense but a poetic memory of a real psychological event – the moment our ancestors first said “I am,” first felt the sting of shame, first plotted the future, first knew good and evil. The Eve Theory of Consciousness gives a framework for understanding this as a memetic and cultural revolution, perhaps driven by women at the dawn of agriculture, spreading through society and encoding itself in myth. It suggests that what Genesis calls “Paradise” was our pre-conscious state, and the “Fall” our break into awareness – a necessary step in nature’s journey to know itself.

As consciousness evolved further, humans in the Axial Age unlocked even deeper insights – recognizing abstract universals and the profound idea that mind and cosmos are linked. This we saw in John’s declaration of the Logos, a concept distilled from centuries of metaphysical exploration. John effectively sanctified meaning itself as divine: in the beginning was Meaning, and that Meaning became flesh to illuminate us. The idea that Logos is the metaphysical substrate – an idea that became thinkable only once minds could handle such abstraction – finds support in how Axial Age sages converged on singular, subtle principles like the Tao, Brahman, or the Form of the Good. Those developments marked the point where humanity started to re-connect the self-aware ego with the universal, finding our true origin not in clay but in mind.

We then saw the fascinating mirror-image reading offered by the Gnostics and Manichaeans. By flipping God and serpent, they in effect shouted a truth mainstream religion had muted: that awakening is divine. Their mythic inversions, heretical as they were, underscore that somewhere in the human psyche was an intuition that gaining knowledge (and with it, selfhood) could not inherently be evil – it was perhaps the very point of our existence. In their poetic language, a jealous lesser god tried to keep us blind, but a higher God sent the serpent (and later Jesus) to open our eyes. Strip away the theological framework, and it aligns with an evolutionary perspective: blind instinct (or authoritarian command) was our initial condition, but insight (even if attained through defiance) is what moves us forward. The cost of that insight – suffering, exile, the burden of freedom – is real, but the Gnostic myth insists it’s worth it, because it leads to eventual reunion with the true Source in knowledge and light.

Finally, we considered how the trauma of becoming conscious may lie at the root of sacrificial rituals and savior myths. The universality of the dying-and-rising god motif, from Osiris to Odin to Christ, suggests humans have long understood that something must die for a new thing to live. In the context of consciousness, that “something” was the unconscious innocence or the bicameral mind of our earlier state. The initiation rituals of tribal societies and the mystical death-rebirth experiences in religious traditions can be seen as reenactments that allow individuals to recapitulate that transformation in a controlled way – to taste death (ego-death) and see the light on the other side. The crucifixion of Jesus became the central symbol in the West for this process: it is both an act in history (for believers) and an internal path (the via crucis of the soul letting go of its old self to be reborn in Christ-consciousness). The correspondences between Christ and earlier figures like the Hanged Odin or the punished Prometheus hint that mythic imagination was circling around the same mystery: the price of consciousness and the promise of transcendence.

In weaving together EToC with all these mythological and philosophical strands, we arrive at a grand narrative of human self-awareness. It is a story of emergence – how from unself-aware hominids arose a creature who could say “I am naked” and eventually “I AM that I AM” (a name of God that, tellingly, is pure self-reference). It is a story of loss and gain – we lost the ease of ignorance but gained the ability to direct our fate and seek truth. It is a story of rebellion – the refusal to remain in mental bondage, symbolized by Eve’s curiosity and perhaps by every philosophical question ever asked against the status quo. And it is a story of integration – the long process of coming to terms with our godlike yet fragile knowledge, of finding a new equilibrium (whether one calls it salvation, enlightenment, or simply wisdom) after the upheaval of the Fall.

For the rationalist reader, this synthesis does not require taking the supernatural claims at face value; rather, it invites admiration for the psychological wisdom embedded in our cultural heritage. These myths and doctrines, when decoded, are like a fossil record of the mind. They preserve in imaginative form the key transitions: from animal awareness to human self-consciousness (Eden), from self-consciousness to philosophical consciousness (Axial Age Logos), from fear of knowledge to embrace of knowledge (Gnostic insight), and from chaotic awakening to structured transformation (ritual and redemption). The beauty of this perspective is that it honors both science and spirituality. It says: yes, consciousness likely evolved through natural, cognitive means – but our ancestors understood its significance through metaphor and story. Instead of dismissing Adam, the Logos, or the Cross as “just myths” or “mere theology,” we find in them a rich, metaphorical record of our own becoming.

In closing, the Eve Theory of Consciousness offers a compelling lens: it suggests that what we consider ancient scripture and esoteric lore is in fact a kind of enduring collective memory – not memory of external events, but of internal events, the formative events of the soul. Genesis remembers our first dawn of mind, John’s Logos remembers the moment we found mind in the cosmos, Gnostic legends remember the valorization of mind against tyranny, and the “hanged god” rituals remember the sacrificial journey mind had to take. Together, they form a mythic chronicle of consciousness. By studying these, we are, in a sense, letting humanity’s earliest and deepest reflections guide us in understanding who we are. After all, in the words of an oft-quoted maxim, myth is something that never happened, but is always happening. The Garden of Eden is always happening – every time a child becomes self-aware. The Logos is always shining in the darkness – every time we seek reason and pattern in the chaos. The Gnostic serpent speaks whenever someone questions authority in pursuit of truth. And the archetype of the Cross or World-Tree manifests whenever we sacrifice comfort for the sake of greater understanding. Our ancestors encoded these truths so that we, inheritors of the age of self-awareness, might not forget the epic journey that brought us here – and might carry that journey onward, with eyes wide open.

FAQ #

Q 1. Did Genesis always portray the serpent as evil? A. No; Gnostic Ophites and Naassenes (2nd c. CE) venerated the serpent as Sophia/Christ bringing liberating gnosis—an inversion later anathematized.

Q 2. How does John’s “Logos” differ from Genesis’s creator God? A. Genesis starts with a divine actor shaping matter; John starts with Logos itself—an eternal rational matrix—so creation is an ontological logic event, not a temporal craft project.

Q 3. Cheat-sheet: Jaynes vs. Eve Theory vs. Axial-Age shift? A.

- Jaynes: Introspection crystallizes ~1200 BCE (bicameral mind collapses).

- EToC: Women spark self-reflection ~10 000 BCE; ritual spreads meme.

- Axial Age: 800–200 BCE, cultures abstract further, naming the substrate (Logos/Tao/Brahman) and universal ethics.

Q 4. Why so many hanged-god myths? A. Cross, world-tree, shamanic ordeals encode ego-death → rebirth; the psyche remembers its first, terrifying step into meta-cognition by staging sacrificial dramas.

Sources#

Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind — Jaynes’s thesis that introspective consciousness is a late cultural invention rather than an ancient biological given. 1

Andrew Cutler, “The Eve Theory of Consciousness,” Vectors of Mind Substack — Proposes a memetic, female-led emergence of self-awareness at the Pleistocene–Holocene boundary. 2

Bernardo Kastrup, More Than Allegory: On Religious Myth, Truth and Belief — A Jung-inflected argument that myths convey literal psychological truths; treats the Fall as the onset of reflexive mind. 3

Karl Jaspers, The Origin and Goal of History — Coins the Axial Age; claims humanity became conscious of Being and self ca. 800-200 BCE. 4

The Gospel of John 1:1-14 (Bible Gateway) — The Logos hymn framing creation as an ontological act of Word/Reason. 5

Tom Butler-Bowdon, “Heraclitus and the Birth of the Logos,” Modern Stoicism — Explains Heraclitus’s Logos as cosmic reason, foreshadowing both Tao and John 1. 6

Frances Young, God’s Presence: A Contemporary Recapitulation of Early Christianity — Explores “serpent-Christ” wisdom imagery and Gnostic inversions of Genesis. 7

“Ophites,” Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) — Survey of serpent-venerating Gnostic sects (Ophites/Naassenes), their cosmology, and their canon of rebel saints. 8

The Nag Hammadi Library in English, trans. James M. Robinson (PDF) — Primary Gnostic texts (e.g., Hypostasis of the Archons) that recast Eden with a liberating serpent-spirit. 9

“The Hanging of Odin and Jesus – Parallels,” Lost History: Dying-and-Rising Gods — Compares Odin’s nine-night self-sacrifice with the crucifixion narrative, highlighting shared initiation symbolism. 10

Mircea Eliade, Rites and Symbols of Initiation — Classic study of global initiation patterns, shamanic death-and-rebirth, and their psychological function. 11

Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels — Landmark analysis of early Christian heterodoxy and the politics of “secret knowledge.” 12

Karen Armstrong, The Great Transformation: The Beginning of Our Religious Traditions — Narrates the Axial-Age shift toward abstract ethics and reflective spirituality across Eurasia. 13

Joseph Campbell, Thou Art That: Transforming Religious Metaphor — Posthumous essays on Judeo-Christian symbols (Garden, Cross, Serpent) as metaphors for inner transformation. 14