TL;DR

- The Olmec civilization (c. 1200-400 BCE) was first discovered in 1862 when José María Melgar found a colossal stone head, initially theorizing it represented “Ethiopian” features and African origins. For comprehensive discussions of African contact theories with the Americas, including the Olmec, see our articles on Pre-Columbian Contacts and Pre-Columbian Trans-Oceanic Contact.

- Early 20th-century archaeologists like Marshall Saville and Matthew Stirling identified the Olmec as a distinct culture, with Alfonso Caso proclaiming them “La Cultura Madre” (the Mother Culture) of Mesoamerica in 1942.

- Fringe theories have proposed various external origins including African (Ivan Van Sertima), Chinese (Gordon Ekholm), and even Atlantean connections, but these lack archaeological support.

- Modern evidence overwhelmingly supports indigenous origins: Olmec skeletal remains show Native American characteristics, DNA analysis confirms local ancestry, and material culture shows continuity with earlier regional traditions.

- The Olmec heartland in southern Veracruz-Tabasco provided ideal conditions for civilization: fertile floodplains for agriculture, abundant resources, and local basalt and jade deposits for monumental art.

Indigenous Traditions and Early Colonial Accounts#

Long before modern archaeology identified the “Olmec” civilization, Mesoamerican peoples had their own traditions about ancient times. The Aztecs (Mexica) later controlled parts of the Gulf Coast and knew it as Olman – literally “The Rubber Country” – due to its latex-producing trees. In the 16th-century Florentine Codex, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún noted a group called Olmeca (or Olmeca-Xicalanca) associated with that region.

This Aztec term olmecatl (“rubber people”) did not refer to the ancient civilization we now call Olmec, but to later inhabitants and traders of the Gulf Coast. Thus the name “Olmec” is an exonym applied by modern scholars – the true name of the Formative-era culture is lost to history.

Mythic Ancestors and Ancient Peoples#

Indigenous myths speak of earlier ages and peoples, although they don’t explicitly mention “Olmecs.” The Aztecs, for example, believed in prior epochs populated by giants (Quinametzin) and others, attributing enormous ancient structures to these mythic ancestors. When the Aztecs beheld ruins like Teotihuacan, they claimed giants had built them in a bygone age. Some later writers speculated that such legends might dimly recall real “pre-Aztec” cultures.

In the Maya area, the Quiché Maya epic Popol Vuh describes multiple creations of humankind (people of mud, wood, etc.) before the current era – again hinting that the Maya recognized a deep antiquity of civilization (though without naming specific cultures). While these myths are not direct evidence of the Olmecs, they illustrate how indigenous people conceived of ancient predecessors.

Modern attempts to link Mesoamerican oral history to the Olmec have been suggestive rather than definitive. For instance, early 20th-century scholars like Bishop Francisco Plancarte y Navarrete tried to connect the legendary paradise Tamoanchan or the Olmeca-Xicalanca people of lore to real archaeological sites. Such correlations remain conjectural.

19th Century: First Archaeological Discoveries and Speculation#

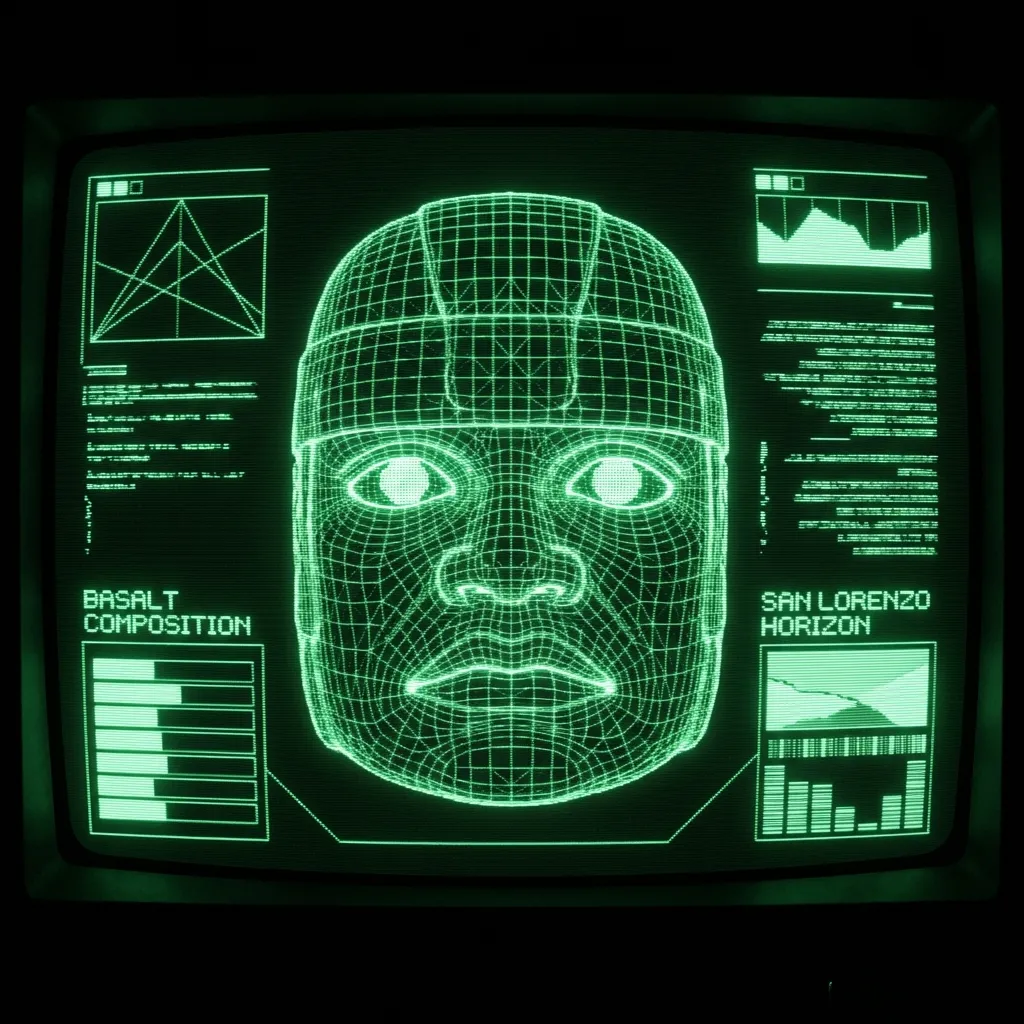

European awareness of the Olmec civilization began in the mid-19th century. In 1862 a Mexican explorer, José María Melgar y Serrano, stumbled upon a colossal stone head half-buried on a hacienda in Tres Zapotes (Veracruz). He published a description in 1869, marveling at the 3-meter sculpted head and remarking on its “Ethiopian” features.

The First “African” Theory#

Melgar was struck by the broad nose and thick lips of the face and concluded that it represented “a Negro” – even positing it was carved by people of “the Negro race”. This is the first recorded theory about the Olmec’s origins: Melgar speculated that Africans must have inhabited Mexico in antiquity. His contemporary Manuel Orozco y Berra and later historian Alfredo Chavero agreed with this interpretation, effectively inserting Melgar’s giant head into pre-Hispanic history as evidence of Black people in ancient Mexico.

This early African-origin hypothesis was a product of its time (when diffusionist ideas ran rampant), and it foreshadowed later Afrocentric claims. Aside from Melgar’s report, 19th-century knowledge of Mesoamerican antiquity was scant. The great Maya ruins in the Yucatán were being revealed in this period, shifting attention beyond the Aztecs. Yet the Gulf Coast lowlands remained largely unknown to outsiders.

Diffusionist Speculation#

Some early Western theorists folded the mysterious “Olmec” relics into grand diffusionist narratives. For example, Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (1882) speculated that an antediluvian mother culture (Atlantis) peopled the New and Old Worlds; discoveries like large stone heads with seemingly “African” traits were seized upon as possible evidence of Old World influence in ancient America.

By the late 1800s, a few colossal heads and greenstone figurines from Veracruz-Tabasco were known in scattered reports, but scholars had not yet identified them with a distinct civilization. Thus, fringe ideas thrived in a vacuum of data – the Olmec heads were alternately attributed to Africans, lost tribes of Israel, or Atlantean survivors in various speculative writings of the era (all lacking proof).

Early 20th Century: Defining a “New” Ancient Culture#

In the early 20th century, more pieces of the Olmec puzzle emerged. By the 1900s, additional Olmec artworks – especially polished jade axes (celts) and figurines with a distinctive style – found their way into museums and private collections. Scholars began noticing that these artifacts, coming from the Gulf Coast, did not fit Maya or Aztec styles.

Academic Recognition#

Marshall H. Saville and Hermann Beyer were among the first to systematically study them. In 1917, Saville published on a set of carved jade axes with strange “baby-like” faces, proposing they came from an unknown culture. Beyer, a German-Mexican archaeologist, compared objects and in 1929 coined the term “Olmec” for this art style. He borrowed the Aztec word Olmeca (“rubber people”) since the artifacts were traced to the rubber-producing Gulf Coast. This marked the first academic use of “Olmec” to designate an ancient culture.

Around the same time, field expeditions began to penetrate the swampy Gulf lowlands. The 1925 Tulane University expedition led by Frans Blom and Oliver La Farge documented sites in Tabasco (publishing Tribes and Temples in 1926). In reviewing their work, Beyer linked a small greenstone figurine they found to a massive stone statue on a mountaintop in San Martín Pajapan (Veracruz), correctly deducing a shared cultural origin.

The Role of Miguel Covarrubias#

Also influential was Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias, who in the 1920s–30s avidly collected and studied carved jades and basalt pieces from the Gulf Coast. Covarrubias recognized the unified aesthetic – jaguar-like faces, “almond” eyes, downturned mouths – and championed the importance of these artifacts in lectures and art exhibitions. By the 1930s, then, scholars had identified a coherent prehistoric culture centered in southern Veracruz/Tabasco, characterized by colossal basalt sculptures and exquisite jade work.

What they didn’t yet know was its age – many assumed it was contemporaneous with or even later than the Maya, since the Maya were then thought to be the hemisphere’s oldest civilization.

1930s–1940s: Archaeological Revelations and the “Mother Culture” Debate#

Matthew Stirling of the Smithsonian Institution, with support from National Geographic, led a series of excavations from 1938 to 1946 that truly discovered the Olmec civilization. At sites like Tres Zapotes, San Lorenzo, and La Venta, Stirling’s teams unearthed monumental art and architecture on a scale previously unseen outside the Maya world.

Groundbreaking Discoveries#

They documented multiple colossal heads (weighing 10+ tons each), giant “altars” (rectangular throne-like stones), and sophisticated ceramics. In 1939 at Tres Zapotes, Stirling found Stela C, a stone monument with a partially eroded Long Count date. His wife, Marion Stirling, deciphered it as 31 B.C. – by far the oldest written date then known in the Americas.

If correct, this meant the Gulf Coast culture was flourishing in the Late Preclassic centuries, long before the Classic Maya. This claim provoked intense debate. The eminent Maya scholar J. Eric S. Thompson was skeptical and “argued with ferocious ingenuity” that the date was misread or used a different calendar era. Thompson even suggested the Olmec sculptures might be Postclassic (after 900 CE) imitations, unwilling to concede that an older civilization could rival the Maya.

The “Mother Culture” Proclamation#

Stirling, however, stood by the evidence, and so did Mexican archaeologists like Alfonso Caso. As more of La Venta’s colossal heads and intricately carved stelae came to light (clearly of non-Maya style), the antiquity of this culture became undeniable. In 1942, the Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología convened a now-famous roundtable in Tuxtla Gutiérrez to discuss “the Olmec problem.”

There, Alfonso Caso and Miguel Covarrubias formally proclaimed the Olmecs as “La Cultura Madre” – the mother culture of Mesoamerica. Caso argued that the Olmec civilization, with its early development (by the 2nd millennium BC) and wide influence, was the fountainhead from which later cultures like the Maya, Zapotec, and Teotihuacanos sprang. This bold claim positioned the Olmec not as a provincial curiosity but as the cradle of New World civilization.

Scientific Validation#

Critically, by the late 1940s and 1950s, new scientific dating (especially the emerging radiocarbon method) vindicated Caso’s view. Charcoal samples from San Lorenzo and La Venta yielded dates in the range ~1200–600 BCE, confirming that these Olmec centers predated the rise of highland cities and the Classic Maya by many centuries. Since 1960, an early first-millennium BC date for Olmec society has been undisputed.

Mid-20th Century: Understanding Indigenous Origins#

With the question of “oldest civilization” settled in the Olmecs’ favor, research in the 1960s–70s shifted to understanding how the Olmec civilization developed indigenously. Archaeologists noted that the Olmec heartland’s rich ecology – well-watered river floodplains for maize agriculture, abundant wild resources (fish, game), and local basalt and jade deposits – could have fostered the rise of complex society.

Evidence for Native American Origins#

Significantly, linguistic and biological evidence began to tie the Olmecs to local indigenous lineages. Linguists studying modern indigenous languages noted that the Mixe-Zoquean language family is prevalent around the Olmec heartland (even today). It was hypothesized that the Olmecs likely spoke a proto-Mixe-Zoquean language, meaning their cultural origins were native to southern Veracruz-Tabasco, not migrants from afar.

Biological anthropology likewise found that Olmec skeletal remains (though scant) fell within the spectrum of Native American populations – in body stature and skull shape, Olmecs matched other Mesoamericans. Recent DNA analysis has confirmed that two sampled Olmec individuals carried mitochondrial haplogroup A, one of the common Native American lineages that arose from Ice Age Asian ancestors.

Persistent Fringe Theories#

Yet, even as mainstream scholars fleshed out an indigenous origin story, some fringe diffusionist theories persisted or emerged in mid-century. A notable example is the idea of a Chinese connection. In the 1950s and 60s, renowned archaeologist Gordon F. Ekholm (of the American Museum of Natural History) became intrigued by similarities between Olmec art and Shang-dynasty China. Ekholm noted, for instance, the motif of a snarling beast with downturned mouth in Olmec art resembled the Chinese taotie monster mask. In 1964 he floated the suggestion that Olmec culture might owe some inspiration to Bronze Age China, positing a transpacific contact.

Around the same time, adventurer Thor Heyerdahl – famous for his Kon-Tiki voyage – argued for Old World voyagers reaching the Americas. Heyerdahl went so far as to claim that certain Olmec leaders could have been of Old World (even Nordic) origin, pointing to the carved depiction of a bearded, aquiline-nosed figure on La Venta Stela 3 (nicknamed “Uncle Sam”) as evidence of a Caucasian visitor.

The 1970s: Afrocentric Theories Gain Attention#

The late 1970s saw a resurgence of interest in the old question raised by José Melgar: did Africans reach ancient Mexico and give rise to the Olmec? In 1976, Guyanese-American professor Ivan Van Sertima published They Came Before Columbus, a work which became hugely influential in African diasporic communities.

Van Sertima’s Hypothesis#

Van Sertima boldly argued that Negroid Africans had sailed to Mesoamerica in antiquity and profoundly influenced the Olmec civilization. Specifically, he hypothesized that Nubian Egyptians of the 25th Dynasty (circa 700 BCE) undertook a voyage with Phoenician help, got caught in Atlantic currents, and landed on the Gulf coast of Mexico. There, according to Van Sertima, these Africans were accepted as ruling elites by the Olmecs – becoming “black warrior dynasts” who kick-started Olmec culture.

As evidence, he and others pointed to the colossal heads with their broad noses and full lips, claiming they depict African facial features (even citing specific supposed “models” among Nubian pharaohs). Van Sertima also asserted that practices like pyramid-building, mummification, and certain art motifs in Mesoamerica were introduced by these Nubian visitors.

Academic Rejection#

While professional archaeologists and historians roundly dismissed Van Sertima’s thesis (as a form of hyperdiffusionism lacking any concrete proof), it nevertheless garnered wide popular appeal. By the late 1980s, his ideas were embraced by some Afrocentric scholars as part of a narrative that Black Africans were founders of all major civilizations.

However, careful scrutiny finds no genuine African artifacts in Olmec contexts, no Old World skeletons, and no DNA of African origin – nothing beyond the subjective “appearance” of some sculptures. Those colossal heads were also created centuries earlier than 700 BCE (the oldest head dates ~1200 BCE, long before any Nubian-Phoenician voyage could be proposed). As one researcher noted, the specific features (flat noses, etc.) are within the range of indigenous Mesoamerican phenotypes, particularly when carved on a massive scale.

Modern Consensus: Indigenous Mesoamerican Origins#

In conclusion, the origins of the Olmec civilization can be best understood as indigenous genius fostered by favorable conditions, which then radiated influence across a connected cultural landscape. From the Aztec memories of a “rubber country” to the latest chemical clay analyses, each chapter of research has added to this story.

Archaeological Evidence#

The material culture speaks clearly: Olmec art and artifacts show a progression from earlier local styles (e.g. the indigenous Barranca phase pottery precedes true Olmec ceramics in Veracruz), and the monumental sculptures, while astonishing, fit within New World sculptural traditions – there’s no need to invoke Egyptian sculptors or Atlantean stonecutters when Native artisans were fully capable of such feats.

As anthropologist Richard Diehl observes, increasing productivity of maize in the Olmec heartland likely led to population growth, social stratification, and the emergence of an elite class by ~1200 BCE. That elite sponsored the colossal head carvings and massive earthworks as power symbols. Olmec society is understood as a collection of chiefdoms rather than a single empire – San Lorenzo and La Venta were major ceremonial centers where several small chiefdoms coalesced for ritual and trade.

Continuing Debates#

While debate will surely continue (as is the case with any great ancient enigma), the trajectory of evidence consistently points to the Olmecs as a people of the New World, who on their own (and in concert with their neighbors) achieved the first American civilization – carving colossal heads and crafting complex societies long before any outsiders arrived.

As for the fringe hypotheses, they have become part of the historiography of ideas – interesting mostly as cultural phenomena. The image of an “African Olmec” or “Chinese Olmec” might persist in popular media, but archaeologists have rebutted these with solid data. The absence of any African skeletal remains and the continuity of Native American genetic markers provide clear evidence for indigenous origins. For more on how archaeological theories and myths about ancient civilizations evolve over time, see our article on The Longevity of Myths.

FAQ#

Q 1. What evidence supports the theory that Olmecs were of African origin? A. The only “evidence” is the subjective interpretation of broad facial features on colossal heads, but these features are within the range of indigenous Mesoamerican phenotypes, and no African artifacts, skeletons, or DNA have ever been found in Olmec contexts.

Q 2. When was the Olmec civilization definitively established as the “Mother Culture” of Mesoamerica? A. In 1942, Alfonso Caso and Miguel Covarrubias proclaimed the Olmecs as “La Cultura Madre” at a roundtable in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, a view later validated by radiocarbon dating showing Olmec sites dated to ~1200–600 BCE.

Q 3. How did the Olmec civilization develop indigenous complex society? A. The Olmec heartland’s rich ecology provided ideal conditions: fertile river floodplains for agriculture, abundant wild resources, and local basalt and jade deposits, allowing population growth and elite emergence by ~1200 BCE.

Q 4. What role did Matthew Stirling play in Olmec archaeology? A. Stirling’s Smithsonian expeditions (1938-1946) at sites like Tres Zapotes, San Lorenzo, and La Venta documented massive colossal heads and found Stela C with the oldest known Long Count date (31 BCE), proving Olmec antiquity.

Q 5. Why do some fringe theories persist despite archaeological evidence? A. Fringe theories like African or Chinese origins persist in popular culture because they fit certain cultural narratives, but mainstream archaeology has consistently found no supporting evidence and overwhelming proof of indigenous development.

Sources#

- Coe, Michael D. & Diehl, Richard A. In the Land of the Olmec. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1980. (Comprehensive archaeological study of Olmec civilization)

- Diehl, Richard A. The Olmecs: America’s First Civilization. London: Thames & Hudson, 2004. (Modern synthesis of Olmec archaeology)

- Pool, Christopher A. Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. (Scholarly overview including discussion of diffusionist theories)

- Blomster, Jeffrey P. “Olmec Pottery Production and Export in Ancient Mexico.” Science 307, no. 5712 (2005): 1068-1072. (Chemical analysis supporting indigenous origins)

- Van Sertima, Ivan. They Came Before Columbus. New York: Random House, 1976. (Influential but disputed Afrocentric theory)

- Ortiz de Montellano, Bernard R., Gabriel Haslip-Viera, and Warren Barbour. “They Were NOT Here Before Columbus: Afrocentric Hyperdiffusionism in the 1990s.” Ethnohistory 44, no. 2 (1997): 199-234. (Scholarly refutation of African origin theories)

- Stirling, Matthew W. “Discovering the New World’s Oldest Dated Work of Man.” National Geographic 76, no. 2 (1939): 183-218. (Original report on Stela C discovery)

- Melgar y Serrano, José María. “Notable escultura antigua mexicana.” Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Geografía y Estadística 2, no. 3 (1869): 292-297. (First published description of Olmec colossal head)

- Caso, Alfonso. “Definición y extensión del complejo ‘Olmeca’.” Mayas y Olmecas (1942): 43-46. (Proclamation of Olmec as “Mother Culture”)

- Covarrubias, Miguel. Indian Art of Mexico and Central America. New York: Knopf, 1957. (Artistic analysis supporting Olmec cultural unity)