TL;DR

- Nüwa and Fuxi are primordial creator deities in Chinese mythology, depicted with human upper bodies and serpent lower bodies, symbolizing their liminal status between human and divine.

- They are commonly portrayed holding a compass (Nüwa) and square (Fuxi), representing Heaven and Earth and the imposition of cosmic order on chaos.

- Similar serpent symbolism appears in many world mythologies, including the Eden serpent in Judeo-Christian tradition, though with different moral valences.

- The prevalence of these motifs across cultures suggests either cultural diffusion or common psychological patterns in human mythmaking.

- These mythological parallels offer insight into how different civilizations conceptualized creation, order, and the human relationship to cosmic powers.

Historical and Mythological Context of Nüwa and Fuxi#

Nüwa (女娲) and Fuxi (伏羲) are central figures in Chinese mythology, often regarded as the primordial couple and culture-bringers of humanity. Early Chinese sources already describe them with serpentine forms.

For example, the Warring States-era poem Tianwen (“Heavenly Questions”) in the Chu Ci states “Nüwa had a human’s head and a snake’s body” (女娲人头蛇身). Similarly, the Han Dynasty Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shanhai Jing) describes Nüwa as “an ancient divine woman and sovereign, human-faced and snake-bodied, capable of seventy transformations in a day” (女娲,古神女而帝者,人面蛇身,一日中七十变). These early texts establish that both Nüwa and Fuxi belonged to a class of creator-deities with human and snake (or dragon) features.

Nüwa is venerated as a creator and savior of humanity. In one legend she molds humans from yellow clay, giving life to the first people.

In another famous myth, Nüwa repairs the broken heavens after a cosmic catastrophe: “The four pillars collapsed, the nine provinces split; heaven could not cover all, earth could not support all… Nüwa smelted five-colored stones to patch the azure sky”. (Original Chinese: “女娲炼五色石以补苍天…”.) In this tale, preserved in texts like the Western Han Huainanzi, Nüwa also fixes the pillars of heaven (using a giant turtle’s legs), slays a venomous dragon, and stops the flood, thereby saving the world.

As a result of such deeds, later sources ennoble her among the Three Sovereigns – legendary rulers of high antiquity – and even record that she was worshipped as a sky-empress or creator goddess (造物主).

Fuxi, in turn, is portrayed as Nüwa’s brother (or elder sibling) and husband. Traditional accounts say the Huaxu clan virgin stepped in a giant’s footprint and miraculously conceived Fuxi.

Fuxi is credited with civilizing innovations: the invention of fishing nets, writing or trigrams, music, and the institution of marriage. In fact, an ancient tradition holds that after a great flood, Fuxi and Nüwa were the only survivors and became the first husband and wife to repopulate the world.

This sibling-marriage creation story appears in multiple early Chinese records. The Taiping Yulan (10th century encyclopedia) recounts, for instance, that Nüwa molded people from clay and then, exhausted by the task, wed her brother Fuxi to jointly continue humanity’s propagation. The idea of Nüwa and Fuxi as the primordial couple — two siblings who unite to ensure human survival — became a common theme in later folklore.

Original Chinese – Chu Ci (Heavenly Questions): “女娲人头蛇身” (Nüwa had a human head and snake body) English translation: “Nüwa had a human’s head and the body of a snake.” This early description from Heavenly Questions (c. 4th century BCE) highlights her hybrid form, which is mirrored by Fuxi in many depictions.

By the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), Nüwa and Fuxi were firmly established as human-serpent hybrids and as the progenitors of the human race. Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian (司马迁《史记》) lists Fuxi as a ruling sovereign of antiquity, and later texts often pair Nüwa with him in lists of ancient rulers or deities. The Han-era scholar Xu Shen, in the dictionary Shuowen Jiezi (《说文解字》, 2nd century CE), defines “娲” (Wa, in Nüwa’s name) as “an ancient divine woman, the one who transformed the myriad things”, underscoring her role as creator. Both Fuxi and Nüwa were thus not only mythic characters but also objects of cult veneration. Nüwa in particular had temples and festivals in her honor (as the Mother Ancestress), and was invoked as a divine matchmaker and protector of women. Fuxi was often honored as well for teaching humans skills and for devising the bagua (Eight Trigrams) used in divination.

In summary, Chinese tradition remembers Nüwa and Fuxi as the first couple and cultural ancestors of humanity. Their union is a cosmogonic marriage that yields civilization itself. Uniquely, they are depicted not as fully human, but as theriomorphic deities—half-human, half-serpent—symbolizing their primal, liminal status at the dawn of creation. This iconography would take on even more significance through the symbols they carry, as we explore next.

Iconography: The Compass and Square Motif#

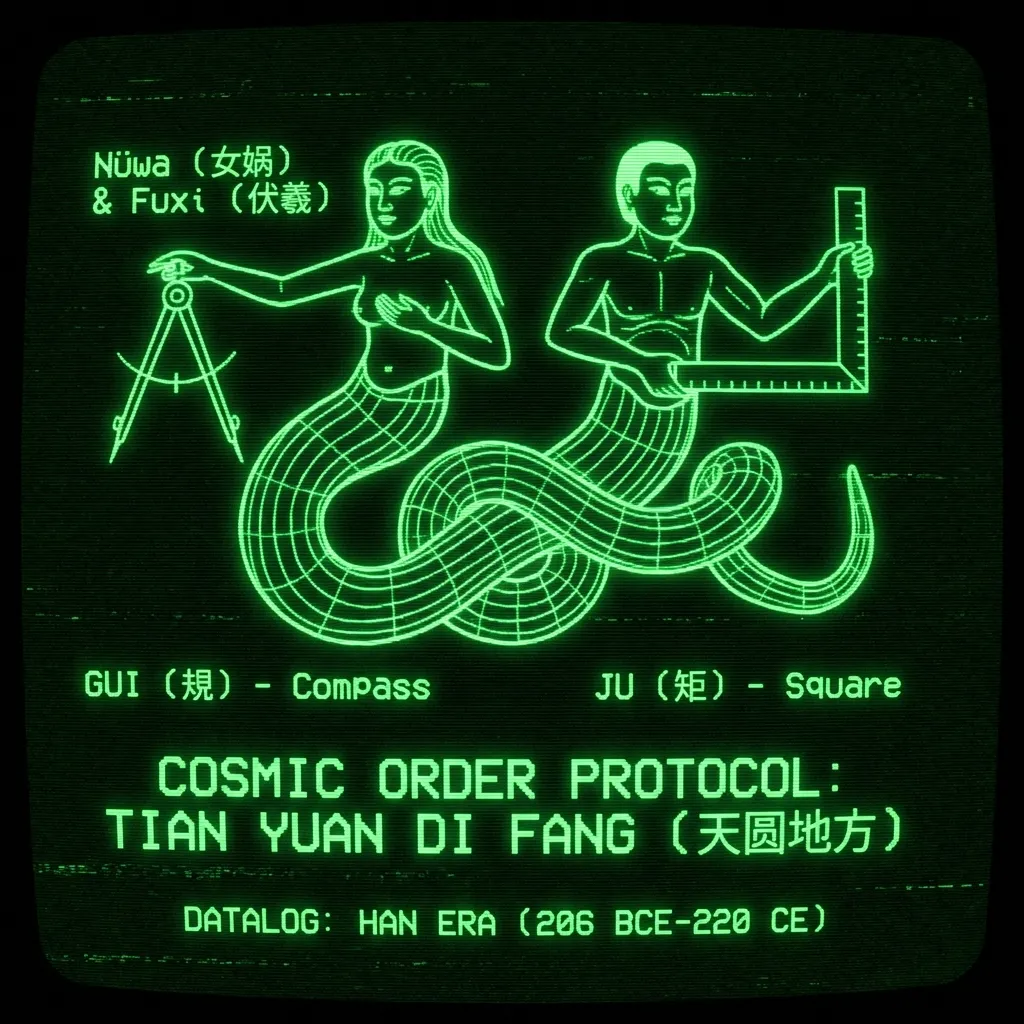

In Han Dynasty art, Nüwa and Fuxi became associated with specific implements: she holds a compass (規, gui) while he holds a carpenter’s square (矩, ju). This pairing persisted for millennia in Chinese art, with the specific iconography crystalizing around the 2nd century CE. For example, in Han Dynasty tomb reliefs from Nanyang, Henan (c. 165 CE), Nüwa and Fuxi are depicted with serpentine lower bodies, facing each other, with Nüwa holding a compass and Fuxi holding a square. This iconography became canonical and can be observed across various media including tomb tiles, stone coffins, bronze mirrors, and later temple murals and painted scrolls. For a deeper exploration of the compass and square symbolism across cultures and traditions, see our article on Square and Compass Analysis.

The symbolism is profound. The compass draws circles, representing heaven, while the square represents earth. In Chinese cosmology, “heaven is round, earth is square” (天圆地方, tian yuan di fang) – a concept directly visualized through these implements. The Chinese term for “compass and square” (規矩, guiju) doubles as the word for “rules” or “standards.” Thus, Nüwa with her compass and Fuxi with his square establish cosmic norms and impose order on primordial chaos. More deeply, the intertwining serpentine forms of the two deities create a figure reminiscent of the taiji (太極, “supreme ultimate”) symbol – representing the complementary cosmic forces of yin and yang, female and male principles united in dynamic balance.

At times, this iconography incorporated additional symbols. In some Han Dynasty stone reliefs, Nüwa and Fuxi are shown with the sun (containing a three-legged crow) and the moon (containing a rabbit pounding the elixir of immortality). In certain variations, they hold not only the compass and square but also the sun and moon disks directly. The significance is clear: they are paired cosmic powers who govern both space (compass and square) and time (sun and moon). They represent the fundamental structuring principles of the universe itself.

Textual evidence from various periods confirms the special significance of this depiction. The Shangshu Dazhuan (尚書大傳, “Great Commentary on the Book of Documents”), from the Han era, links Fuxi explicitly with the square and the regulation of earth: “Fuxi drew the eight trigrams and established the square to determine the four cardinal directions, thereby instituting regulations for earth”. Similarly, Tang Dynasty commentator Kong Yingda wrote that “Nüwa held the compass to establish the heavens”. This cosmic role of the two deities – ordering and harmonizing the universe through their implements – became a distinctive feature of Chinese mythological art.

Global Parallels: Serpent Symbolism in Other Cultures#

The serpentine attributes of Nüwa and Fuxi find intriguing parallels in world mythologies. Most prominently, the Biblical serpent in Eden (Genesis 3) offers knowledge to the first human couple – albeit with very different moral implications than in the Chinese tradition. While Nüwa and Fuxi are benevolent culture-bringers, the Eden serpent’s gift of knowledge is framed as disobedience against divine command. This contrast reflects different cultural attitudes toward knowledge acquisition—compare the serpent myths of the Americas where snakes often appear as wisdom-bringers. Nonetheless, both narratives connect serpent beings with primal human knowledge and the transition from innocence to civilizational awareness.

Ancient Mesopotamian myths feature Ningishzida, a serpent deity associated with fertility and the underworld, sometimes depicted as a human-headed serpent or as two intertwined serpents. Similarly, in Egyptian mythology, Wadjet, the cobra goddess, protected pharaohs and was associated with sovereignty and divine authority. The iconography of intertwined serpents also appears in the caduceus symbol associated with the Greek Hermes and in the rod of Asclepius in Greco-Roman culture.

In Mesoamerican traditions, feathered serpent deities like Quetzalcoatl (Aztec) and Kukulkan (Maya) were revered creator gods and culture-bringers who taught humans arts, agriculture, and calendar systems. The visual similarities to the Chinese serpent deities are remarkable, suggesting either diffusion of symbols or common psychological patterns in mythmaking.

In Hindu iconography, nāgas (divine serpent beings) are often depicted with human upper bodies and serpent lower bodies, recalling the hybrid form of Nüwa and Fuxi. Lord Vishnu reclines on the cosmic serpent Shesha (or Ananta), who represents eternity and the foundation of cosmic existence. The symbolism of the serpent as simultaneously chthonic (earth-bound) and cosmic parallels the dual nature of Nüwa and Fuxi as both earthly ancestors and celestial deities.

Even in Norse mythology, the Midgard Serpent (Jörmungandr) encircles the world, biting its own tail in the ouroboros motif – a symbol of cosmic wholeness and cyclical time. This connects to how Nüwa and Fuxi’s intertwining bodies often form a circular pattern in Chinese art, suggesting cosmic wholeness.

The compass and square symbolism also finds analogues in Western traditions. In Freemasonry, the square and compass became central emblems, representing moral virtues and the harmony between heaven and earth – an interpretation strikingly similar to the Chinese understanding of these tools. While Masonic usage developed independently, the parallel suggests a cross-cultural tendency to invest these geometric tools with cosmic significance.

First Couple and Serpent Archetypes Around the World#

The archetype of a first couple associated with a serpent/dragon or creation by entwined beings is found in various cultures worldwide. A comparative look at global mythologies reveals both parallels and unique variations:

- Mesopotamia & Near East: Ancient Mesopotamian creation stories don’t center on a human couple, but serpents and dragon-like beings do appear. In Babylonian myth, the primordial forces include Tiamat, a chaos dragon (often described as serpent-like) who, together with Apsu, gives birth to the first generation of gods. While not human, this primeval dragon mother and her consort are a serpent-couple at creation’s dawn. In Sumerian lore, after the flood, the hero Gilgamesh seeks a plant of immortality only to have it stolen by a snake – a tale that, like Genesis, links a serpent to the loss of paradise. In Zoroastrian (Persian) tradition, the first human pair Mashya and Mashyane were created by the supreme god Ahura Mazda but later deceived by the evil spirit Ahriman, sometimes envisaged as a lying serpent or dragon. The persistent presence of a malevolent serpent in Near Eastern creation/fall myths (from Eden’s snake to Zoroastrian and perhaps even earlier Dilmun tales) suggests a regional motif of the serpent as the corrupter of the first humans, in contrast to the Chinese serpent-deities who are benefactors.

- South Asia (Indus & Vedic): The ancient Indus Valley civilization left no written myths, but serpent worship was evidently common (cobra motifs, nāga icons). In later Hindu mythology, we find serpents in cosmic roles: the giant serpent Shesha who supports the earth, or Vasuki who is used as a churning rope in the cosmic Ocean of Milk. While the first humans (Yama and Yamī, or Manu and Shatarupa in Hindu lore) are not snake-related, Indian myth does feature a first man (Manu) saved by a horned fish avatar (Matsya) – a different animal motif. However, Hindu and Buddhist traditions revere Nāgās (serpent beings) as fertility and rain deities. The fusion of human and snake is seen in figures like Nāga Kanya (serpent maidens) but these are lesser nature spirits, not creators. One could say India’s equivalent of the beneficent serpent archetype is the Nāga kingdom, yet it is not tied specifically to a single first couple narrative. Still, the prominence of serpent symbolism in early Indian context (the cobra cults, the snake on Buddha’s path, etc.) shows a widespread reverence for serpents as ancient powers of life, death, and rebirth, much like in other cultures.

- Greco-Roman: Greek mythology offers intriguing serpent-couple parallels. In one Pelasgian creation account (reported by ancient sources and later by Robert Graves), the goddess Eurynome (a Mother goddess) dances with a giant serpent Ophion; the two mate, and Eurynome lays the world egg, with Ophion coiled around it until it hatches. This goddess + serpent as world creators is strikingly close to a “first couple and serpent in one” motif – Eurynome and the snake are partners in creation. Another Greek example is Echidna, mentioned above: Hesiod describes Echidna as “half beautiful maiden and half fearsome snake”, who, with her mate Typhon, spawns many creatures. Though Echidna and Typhon are cast as monstrous and not the makers of humanity, the image of a serpentine woman and her consort is there in Greek thought. The Orphic tradition similarly had the cosmic serpents Chronos (Time) and Ananke (Necessity) entwined around the primordial egg of creation. These classical myths underscore that serpent-human hybrids and entwined serpents were potent symbols of creation and primordial power around the Mediterranean as well. Later, Gnostic traditions in late antiquity even reinterpreted the Genesis story in a positive light – with the snake (often named Sophia or a wise entity) as a bringer of knowledge. Thus, the West has both aspects: the negative serpent in mainstream Judeo-Christian lore, and the more ambivalent or positive serpent in esoteric or earlier traditions. This mirrors the dual role of serpents as either chaos or creation. For a detailed exploration of Orphic cosmogony, see our article on Orphic Cosmogony.

- Mesoamerica: In Mesoamerican cosmogony, serpents are deeply revered as creator beings. The Maya Popol Vuh describes the world’s creation by the joint efforts of Tepeu (a sky deity) and Gukumatz (the plumed serpent). Gukumatz (Kukulkan/Quetzalcoatl in other Mesoamerican cultures) is literally a serpent deity with feathers, who speaks and brings forth the Earth and life. Though not a human couple, the duality of a sky god and a serpent god acting in concert is reminiscent of the Heaven-Earth pairing of Fuxi and Nüwa. Aztec mythology tells of Quetzalcoatl creating humans by going to the underworld and recovering the bones of previous races, then bleeding on them – an earth-maker role often assisted or mirrored by a twin (Tezcatlipoca). In some depictions Quetzalcoatl is joined by his female counterpart (e.g. the Aztec snake goddess Coatlicue or others in certain myths), but a clear “Adam and Eve” pair is absent. Instead, we do have a flood survival story: a human couple Tata and Nena escape a deluge in a boat (an echo of Noah) but are turned into dogs for disobedience. While no serpent is involved there, the broader Mesoamerican emphasis on snake deities in creation (the plumed serpent as creator and civilizer, present from Olmec times onward) provides a thematic parallel to China’s serpent creators. The imagery is also remarkably convergent: a sculpture from ancient Mexico might show two serpents intertwined (e.g. the double-headed serpent in Aztec art), symbolizing duality or the union of celestial and terrestrial forces – not unlike Fuxi and Nüwa’s twining tails.

- Middle East & Africa: In Near Eastern and African myths, we also find first couples and serpents. For example, in some Mesopotamian traditions, after the flood the restored human population begins with a new first couple (such as Utnapishtim and his wife, the flood survivors – paralleling Fuxi and Nüwa as flood survivors in Chinese myth – though here there is no snake element beyond a snake stealing the plant of life). In African mythology, there are strong serpent symbols: the Fon (Dahomey) people say the creator Nana-Buluku had twins Mawu (female) and Lisa (male) who married and created humanity, and they were assisted by the rainbow serpent Aido-Hwedo who carried them and supports the earth’s weight in coils. This comes very close to the idea of a first divine pair with a serpent intertwined around the world. Australian Aboriginal traditions revere the Rainbow Serpent as well, often a lone creator or shaper of the land, but sometimes paired with a consort in various stories (in some versions, there are two rainbow serpents of opposite gender who meet). In Aboriginal Dreamtime, the Rainbow Serpent is a primeval being bringing life and fertility, paralleling Nüwa’s role in shaping creatures. Again, while not cast as a human couple, the union of two serpents or a serpent with a creator is a recurring theme.

From this global survey, we see a recurring pattern of serpents in creation: either as part of a first couple (China’s Fuxi/Nüwa, Greek Eurynome/Ophion), or as an adversary to the first couple (Biblical Eden, Persian Ahriman vs. Mashya and Mashyane), or as the sole creators (Rainbow Serpent, Quetzalcoatl). The entwining of male and female to engender the world is nearly universal – sometimes the pair are anthropomorphic (Adam and Eve), sometimes zoomorphic (Sky Father and Earth Mother in the form of animals, or cosmic serpents mating). The serpent, with its chthonic, mysterious nature and its habit of shedding skin (symbolizing rebirth), is naturally associated with creation, fertility, and the cyclical renewal of life. Many cultures probably arrived at this symbol independently; in other cases, motifs may have diffused along trade routes and migrations. Next, we consider how such diffusion or common origin might have occurred, particularly in light of ancient connections like the Silk Road and even prehistoric sites like Göbekli Tepe.

Diffusion and Common Origins of the Motif#

Could the striking similarities in these myths be the result of cultural diffusion, or do they point to a common proto-mythology shared by early humans? Scholars have long debated whether myths like those of a world-creating serpent couple arose independently in different corners of the world or spread from a single source.

The Silk Road hypothesis: Since Fuxi and Nüwa’s iconography appears vividly in a Tang-era painting from Xinjiang (essentially the Silk Road nexus), one might wonder if ideas from West and East mingled. The Silk Road was active by the Tang dynasty, allowing exchange of art and religious motifs between China, Central Asia, India, and the Middle East. However, the Chinese motif of the intertwined serpent couple is attested much earlier (Han Dynasty, centuries before significant Silk Road transmission of myths). It’s possible that the image of a serpent-human hybrid as a primal being has very ancient roots in Central Asia that pre-date written history, and both East and West inherited it. Alternatively, some have speculated that post-Biblical influences seeped into Chinese thought during late antiquity (e.g. Manichaean missionaries in Tang China told of Adam and Eve), but there is scant evidence that Nüwa and Fuxi’s story was influenced by Judeo-Christian lore – the Chinese narratives show no trace of a moralized fall or Garden element, for instance. If anything, Chinese scholars in the 17th–18th centuries (and Jesuit missionaries like Matteo Ricci) compared the flood legends and noted parallels between Nüwa and the Biblical Eve/Noah figure, but that was a much later intellectual exercise. In antiquity, independent development is the simpler explanation, though trade routes may have carried broad ideas (for example, dragon imagery was ubiquitous across Eurasia).

Prehistoric origins: Recent archaeological finds push organized myth-telling back to the Ice Age. The site of Göbekli Tepe (c. 9500 BCE) in modern Turkey provides tantalizing clues. Göbekli Tepe is a series of stone enclosures decorated with carved animals – notably, snakes are one of the most common motifs on its pillars. Some researchers (outside mainstream archaeology) have gone as far as calling it “the world’s first snake temple”. The prevalence of snake imagery at this early communal site suggests that serpent worship or symbolism was significant to early Neolithic people. One speculative theory (dubbed the “Eve Hypothesis” by a blogger discussing Göbekli Tepe) proposes that the concept of a sacred serpent and a mother goddess or first woman could trace back to this deep prehistory. As humans dispersed, the theory goes, they carried variations of a “first mother + serpent” story, which later evolved into Nüwa-Fuxi in the Far East, Adam-Eve and the Serpent in the Near East, and similar patterns elsewhere.

While direct evidence is lacking, it is true that snake iconography is nearly universal in ancient sites – from Neolithic rock art to Egyptian and Mayan pyramids, serpents abound. Some anthropologists suggest that humans have an innate fascination or fear of snakes (occasioned by evolution) which made snakes potent religious symbols from the very beginning of ritual behavior. A provocative piece of evidence for the antiquity of serpent myth is a 70,000-year-old rock in Tsodilo Hills, Botswana, carved in the shape of a giant python, with indications of ritual activity around it – arguably one of the oldest known ritual sites, hinting at proto-religious serpent veneration. If early Homo sapiens venerated a great snake spirit, then as myths diverged, this could have given rise to snake creator stories in many cultures.

Diffusion vs. independent invention: It’s likely a bit of both. The Silk Road could explain transmission of some motifs between India, Iran, and China (for instance, Indian Nāga images influencing Chinese dragon imagery, or vice versa – the Chinese even identified India’s Buddha at times with a serpent-bodied deity to accommodate local iconography). The close correspondences between Eurasian myths – like the widespread flood myth and sibling-marriage motif from the Middle East to China – strongly suggest cross-pollination. In fact, the brother-sister repopulation story exists in the Middle East (the tale of Yima in Iran, or of Deucalion and Pyrrha in Greek myth who are cousins) and in Southeast Asia as well. This particular motif (incestuous first couple after a flood) might have a common origin or reflect a logical narrative solution many cultures arrived at independently to explain human origins after a catastrophe.

When it comes to the square and compass motif, diffusion seems less likely – it appears to be distinctly Chinese in antiquity. There is no evidence that, say, the Greeks or Indians depicted their deities with those tools in the same manner. The closest Western parallel – God with a compass – emerges in the high Middle Ages, likely independently as an allegorical image. The fact that Freemasons in Europe later cherished the same tools is probably coincidence, born of the universal importance of those instruments in building and geometry. However, the entwined male-female serpents motif does have a potential diffusion trail: for example, some have compared Fuxi and Nüwa to the caduceus symbol (two snakes entwined on a staff) which originated in the Near East (associated with the Greek god Hermes, but found in Mesopotamian art as two copulating snakes). Could travelers along the Silk Road have brought tales or symbols of intertwined serpents that reinforced the Chinese image? The Astana paintings from Turpan (on the Silk Road) show the motif clearly in the Tang era, but we know it was present in Han China too, so it was not imported during Tang. It may be that this symbol sprang up in multiple regions because it is visually and conceptually compelling: a unity of opposites (male-female) and a spiraling infinity (the twining coils) suggesting eternity or continuity of life.

In essence, the serpent couple motif could represent a very ancient stratum of myth – perhaps dating back to early agricultural or even hunter-gatherer cosmologies – that then diffused and morphed. Or it could be that humans everywhere, observing the cyclical shedding of snakes, the mating of creatures, and the union of sky and earth (often seen as father and mother), arrived at analogous stories.

Mythological Phylogenies and Common Roots#

Modern comparative mythology has attempted to map out “phylogenetic trees” of myths, much like family trees of languages. Researchers ask: do myths that share motifs (like a creation involving a serpent or a first couple) descend from an ancestral narrative, or are they products of convergent evolution? One ambitious framework is proposed by scholar E. J. Michael Witzel in The Origins of the World’s Mythologies (2012). Witzel suggests that most of the myths across Eurasia and the Americas belong to a common super-family he calls “Laurasian” mythology, which ultimately traces back to the migration of modern humans out of Africa. In Witzel’s view, Laurasian myths (which include those of ancient China, Mesopotamia, Greece, etc.) share a structured “storyline”: beginning with creation from chaos, a sequence of ages, a flood, and eventual heroes – much like chapters in what he terms “the first novel.” The story of Fuxi and Nüwa, with its creation and flood elements, would fit into this Laurasian pattern, as would the Adam and Eve narrative (creation, temptation, fall – which is a kind of loss-of-golden-age akin to a flood narrative in function). Witzel contrasts these with what he calls “Gondwanan” mythology (myths from sub-Saharan Africa, New Guinea, Australia, etc., which often lack a grand chronological narrative). Intriguingly, even some Gondwanan myths (African, Australian) have serpent creators or first couples, which Witzel might argue are either independent or very archaic motifs possibly dating to the earliest human storytelling before the Laurasian “novel” developed.

Other researchers have used computational methods to trace myth diffusion. For example, folklorist Julien d’Huy has applied phylogenetic algorithms to flood myths and dragon-slayer myths, finding that certain myth motifs statistically appear to radiate from a central origin (often matching human migration patterns). These studies sometimes suggest that some mythic ideas could be tens of thousands of years old. A study in Science (2016) used phylogenetic analysis on Indo-European folk tales and found some (like the “smith and the devil” story) might date back to the Bronze Age or earlier. While creation myths weren’t the focus there, it demonstrates the principle that myth motifs can be very conservative, passed down over millennia with incremental changes.

Scholars like Joseph Campbell and Mircea Eliade took a more thematic approach, noting archetypes like the Hero’s Journey or the Great Mother across cultures but without necessarily claiming a single origin. More recently, some have proposed that because humans share similar cognitive and social needs, similar myths can emerge independently (the structuralist school of mythology, e.g. Claude Lévi-Strauss, would emphasize underlying binary oppositions in the mind that produce comparable myths). However, the presence of detailed similarities (like a serpentine first couple with measuring tools) is harder to attribute to pure coincidence and invites at least a hypothesis of diffusion or common heritage.

One theoretical framework posits an ultimate “Out of Africa monomyth” – that as a small band of humans left Africa ~70,000 years ago, they carried with them some proto-myths which then diversified. If Nüwa and Fuxi and Adam and Eve have a common ancestor story, it would be exceedingly old and greatly transformed by time. Perhaps it was something as simple as “In the beginning, a great mother and father shaped the world; the mother was associated with a snake.” Over tens of thousands of years, that could splinter: in one line the mother becomes a literal snake (China), in another the snake becomes the tempter of the mother (Near East).

Another approach is to build myth motif databases (like Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index) and see their distribution. For example, a motif “Half-human, half-snake creator” appears in East Asia (Fuxi, Nüwa), and also in some Native American myths (some Pueblo tribes speak of a snake maiden, and certain Amazonian myths have snake-human ancestors). Could those be connected? Or “First siblings marry to populate earth” – found in Asia, Europe, Pacific islands. The wide distribution suggests great antiquity or multiple reinvented instances. Some Chinese scholars (e.g. Yang Lihui in Handbook of Chinese Mythology) have traced how the brother-sister marriage myth of Nüwa spread and varied even within China, indicating it may have started as an oral myth in antiquity and was reshaped over time. When similar sibling-marriage stories pop up in distant lands, it’s tempting to see a distant connection.

In sum, scholarly attempts to chart myth genealogies indicate that stories like that of a serpent and first couple are among the oldest and most persistent. Whether through ancient diffusion (perhaps along early human migration routes through Eurasia) or through parallel development due to shared human psychology, we cannot be certain. What is clear is that by the time of recorded history, the Chinese had a fully fleshed myth of a serpent-bodied First Couple holding the instruments of creation, and the Near Eastern peoples had their own tale of a First Couple and a paradigm-shifting Serpent. Comparative mythologists will continue to puzzle out the connections, but the symbolic themes – creation, order, knowledge, and the role of the serpent – seem to form a common thread that ties together humanity’s disparate traditions about our beginnings.

Conclusion#

Nüwa and Fuxi stand out in world mythology as a vivid embodiment of the union of male and female principles, human and animal, heaven and earth. As the First Couple of Chinese lore, entwined in serpent form and armed with compass and square, they encapsulate a vision of creation that is at once material (measuring out the land) and mystical (coiling in an eternal dance). When placed in a global context, their story invites fascinating comparisons – from Adam and Eve’s fateful brush with a serpent—detailed in the Eve Theory of Consciousness—to far-flung legends of serpentine creators and world parents. These parallels suggest that the image of “the first man and woman, and the serpent of life” taps into a deep reservoir of the human imagination. Whether this motif arose from a common primordial story or simply from common human experiences, it has left an indelible mark on the mythic landscapes of many peoples.

The square and compass, in the hands of Fuxi and Nüwa, symbolize that the world has been made geometric, structured, and livable. Thousands of years later, those same symbols would be used by stonemasons and moral teachers to signify ethical order. And the serpentine tail that Fuxi and Nüwa share coils not only around each other, but around the globe in various guises – from the Rainbow Serpent of Australia to the feathered serpent of Mesoamerica – connecting the world’s creation myths in a spiral thread.

By studying Nüwa and Fuxi, we gain insight into how early Chinese saw the cosmos: as a union of complementary forces measured out with precision and brought to life through a marriage of heaven and earth. By comparing them with Adam and Eve and others, we also see the enduring power of certain symbols (the woman, the man, the snake, the tool, the union, the transgression) in explaining our origins. In the end, whether born from one source or many, these myths speak to shared questions that humanity has asked for millennia: Where do we come from? Who were the first of us? How did order emerge from chaos? The answers, told in various tongues, often invoke a sacred serpentine dance and the drawing of a divine circle and square.

Creation Myths: Repairing the Sky and Molding Humanity#

The mythology surrounding Nüwa as a cosmic repairer is particularly significant. According to the Huainanzi, there was a time when “the pillars of heaven were broken, the corners of the earth collapsed… fire blazed without being extinguished, water flowed without stopping”. In this time of cosmic catastrophe, Nüwa melted stones of five colors to patch the azure sky, cut off the legs of a great turtle to establish the four pillars at the corners of the earth, killed a black dragon to save the flooded land, and gathered reeds and burned them to ash to stop the flooding waters.

This narrative presents Nüwa as a divine problem-solver who restores cosmic order through practical means—patching, propping, killing threats, and using natural materials as solutions. The story bears striking parallels to flood myths worldwide, from the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh to Noah’s Ark in the Hebrew Bible. However, unlike Noah who saves only selected beings from divine punishment, Nüwa actively repairs cosmic damage to restore balance.

As a creator of humanity, Nüwa’s methods varied across different textual traditions. The Fengsu Tongyi (風俗通義, “Comprehensive Meaning of Customs”) relates that Nüwa “pinched yellow earth and fashioned humans”. More elaborate versions describe Nüwa first carefully crafting figures from yellow clay, but finding the process too slow, she later dipped a rope in mud and flicked it so that mud droplets became common people—explaining the origin of social hierarchy between nobles (handcrafted) and commoners (mass-produced).

This clay creation motif echoes across world mythologies. In Mesopotamian myths, Marduk creates humans from clay mixed with the blood of a slain god. Genesis 2:7 describes how God formed man “from the dust of the ground”. In Greek mythology, Prometheus shaped humans from clay. The consistent use of earth materials for human creation across diverse cultures points to intuitive connections between human flesh and the soil that sustains life.

The distinction between Nüwa’s early humans (crafted carefully) and later ones (created by flicking mud droplets) has analogues in other traditions where humanity is formed in successive “batches” of varying quality. In the Maya Popol Vuh, the gods make several failed attempts at creating humans from mud, wood, and other materials before successfully using maize. In Greek myth, Hesiod’s ages of humanity (golden, silver, bronze, heroic, and iron) suggest successively inferior creations.

Marriage and Incest Themes in Primal Creator Pairs#

The sibling marriage of Nüwa and Fuxi presents a common mythological motif found across cultures—divine incest as a necessary first step in creation. The Late Han Dynasty text Fengsu Tongyi explains: “Brother and sister were husband and wife… in remote antiquity, when there were no other people”. This marriage was justified through a divine omen: the siblings prayed at Mount Kunlun, each burning a separate pile of incense. When the smoke from both piles merged rather than separating, they took it as heavenly approval of their union.

This theme connects to similar motifs in Egyptian mythology, where divine siblings Isis and Osiris marry and become the model for pharaonic marriages. In Greek tradition, the primordial pair Gaia and Uranus (Earth and Sky) produce offspring together, as do Zeus and Hera, who are siblings. Norse mythology portrays the first beings, Ymir and Bestla, as producing children without a separate mate. In Hindu mythology, Brahma creates his daughter Saraswati and subsequently marries her.

This recurring mytheme—incestuous creation—reflects a logical problem in creation narratives: how does reproduction begin if there is initially only one being or one pair? Mythologies frequently resolve this through divine exception to human taboos. These myths also often contain a transition point where divine incest gives way to exogamy (marriage outside the immediate family) for humans. In the Chinese tradition, it’s significant that while Nüwa and Fuxi’s marriage was considered cosmologically necessary and divinely sanctioned, Chinese culture developed strong incest taboos for humans, enforced by both law and custom since at least the Zhou Dynasty.

Comparatively, Nüwa and Fuxi’s specific iconography as entwined serpents recalls the ancient Near Eastern caduceus symbol, with its twin serpents in eternal embrace. In Tantric Hindu art, the union of masculine and feminine cosmic principles is often represented by intertwining serpents or snake deities. These cross-cultural connections suggest either cultural diffusion along the Silk Road or independent development from common psychological archetypes—both possibilities revealing deep patterns in human mythic imagination.

Cultural Legacy and Contemporary Significance#

The enduring impact of Nüwa and Fuxi extends far beyond ancient texts and artifacts. Throughout Chinese history, these figures have been continuously reinterpreted within evolving cultural, philosophical, and political contexts. During the Han Dynasty synthesis of philosophical schools, Nüwa and Fuxi were incorporated into correlative cosmology as embodiments of yin and yang principles. The Tang and Song Dynasties saw them increasingly associated with the I Ching (Book of Changes) tradition, with Fuxi credited as the discoverer of the eight trigrams.

The symbolism of Nüwa as cosmic repairer resonated particularly during periods of dynastic collapse and transition. For instance, at the fall of the Han and Ming Dynasties, literati frequently referenced Nüwa’s sky-mending as a metaphor for the need to repair the social and political order. This reveals how creation myths could function as political allegories during times of societal crisis.

In contemporary China, Nüwa and Fuxi have experienced various reinterpretations. During the early 20th century, nationalist scholars emphasized their role as progenitors of the Chinese people to foster national identity. In the mid-20th century, they were sometimes reframed through the lens of historical materialism as symbols of primitive society and early technological innovation. More recently, these figures have been embraced as cultural heritage symbols, appearing in everything from regional tourism promotions to modern art installations.

Archaeological findings continue to shed new light on these mythological figures. Discoveries at sites such as Taosi in Shanxi Province have revealed prehistoric artifacts with serpentine imagery dating to the 3rd millennium BCE, suggesting origins of serpent worship that may predate written records. Such deep historical continuity demonstrates the longevity of myths across millennia. Similarly, the ongoing excavation of Han Dynasty tombs continues to yield new examples of Nüwa-Fuxi iconography, allowing for more nuanced understanding of their religious significance.

Globally, the study of Nüwa and Fuxi myths contributes to comparative mythology and anthropology in several ways. First, their narratives provide important data points for scholars studying creator couples and divine twins across cultures. Second, the serpent attributes of these deities offer evidence in debates about the origins and diffusion of serpent symbolism along ancient trade routes. Finally, their continued evolution across three millennia of Chinese civilization provides a model for understanding how ancient myths can remain relevant through continuous reinterpretation.

The remarkable persistence of Nüwa and Fuxi in Chinese culture, from Neolithic painted pottery to contemporary cinema, speaks to their archetypal power. Their dual nature as serpents and humans, their complementary gender aspects, and their roles as both creators and preservers of cosmic order resonate with fundamental human concerns about origins, social structure, and the relationship between nature and culture. In this way, these ancient deities continue to function as powerful symbols through which Chinese culture has repeatedly reimagined its relationship to the cosmos, humanity, and its own history.

FAQ#

Q1. Why the compass and square—what do they symbolize?

A. In Han iconography Nüwa’s compass and Fuxi’s square figure Heaven/Earth order; together they codify cosmic geometry imposed on chaos, matching their roles as culture‑bringers.

Q2. Do their serpent bodies mean they’re “snake gods”?

A. The hybrid human‑serpent form marks liminality and creative potency. They interact with flood/dragon forces but function primarily as creators/preservers of order, not merely snake deities.

Q3. Is the sibling‑marriage a flood‑survivor motif?

A. Many sources pair them as sole survivors who repopulate the world—a Chinese variant of re‑creation myths that follow catastrophe, aligning with broader global patterns.

Q4. Diffusion or coincidence with other serpent‑creation myths?

A. Both are plausible contributors. The essay treats Nüwa–Fuxi as a robust indigenous complex that also resonates with recurrent human symbolics (serpent, tools, first couple).

Sources#

- Chu Ci – “Heavenly Questions” (《天问》). c. 3rd c. BCE. (Attrib.) Qu Yuan. Available at: https://ctext.org/chu-ci/tian-wen

- Shan Hai Jing (《山海经》, “Classic of Mountains and Seas”). 4th–1st c. BCE. Anonymous (compiled). Available at: https://ctext.org/shan-hai-jing

- Huainanzi (《淮南子》). 139 BCE. Liu An et al. Available at: https://ctext.org/huainanzi

- Shuowen Jiezi (《说文解字》). c. 100 CE. Xu Shen. Available at: https://ctext.org/shuo-wen-jie-zi

- Taiping Yulan (《太平御览》). 984 CE. Li Fang (ed.). Available at: https://ctext.org/taiping-yulan

- Lu Shi (《路史》). 11th c. Luo Mi. (1611 print available at: https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/73588)

- Genesis 2–3 (The Fall). 6th–5th c. BCE. The Holy Bible. Example NIV version: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Genesis+3&version=NIV

- Theogony. c. 700 BCE. Hesiod. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/348

- Popol Vuh. c. 1550 CE (transcribed). K’iche’ Maya. English translation example: https://sacred-texts.com/nam/pvuheng.htm

- Han Dynasty Tomb Art (e.g., Mawangdui, Nanyang). c. 1st–2nd c. CE. Depicting Fuxi & Nüwa with compass/square and interlaced tails.

- Lai Guolong. “Iconographic Volatility in the Fuxi-Nüwa Triads of the Han Dynasty.” Archives of Asian Art 71, no. 1 (2021): 63–93. https://read.dukeupress.edu/archives-of-asian-art/article-standard/71/1/63/173731/Iconographic-Volatility-in-the-Fuxi-Nuwa-Triads-of

- Silk painting “Fuxi & Nüwa” (Astana Cemetery, Turpan). 8th c. CE. Tang Dynasty. Image available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fuxi_and_N%C3%BCwa._1967_Astana_Cemetery.png

- Michelangelo. “Fall and Expulsion from the Garden of Eden.” c. 1512. Sistine Chapel. Example image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Michelangelo,_Fall_and_Expulsion_from_Garden_of_Eden_00.jpg

- Christian Iconography website. “Adam, Eve, and the Serpent: Sistine Chapel Detail”. Commentary on Michelangelo’s depiction. (Link unavailable)

- Allan, Sarah. The Shape of the Turtle: Myth, Art, and Cosmos in Early China. SUNY Press, 1991.

- Yang, Lihui, Deming An, and Jessica Anderson Turner. Handbook of Chinese Mythology. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Birrell, Anne. Chinese Mythology: An Introduction. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- Maspero, Henri. China in Antiquity. Translated by Frank A. Kierman Jr. University of Massachusetts Press, 1978.

- Witzel, E.J. Michael. The Origins of the World’s Mythologies. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Eliade, Mircea. Patterns in Comparative Religion. Translated by Rosemary Sheed. Sheed & Ward, 1958.

- Dundes, Alan (ed.). The Flood Myth. University of California Press, 1988.

- Frazer, James George. Folklore in the Old Testament: Studies in Comparative Religion, Legend and Law. Macmillan, 1918.

- Baker, Joel. “Readings on the Square and Compass”. Lecture, Novus Veteris Lodge, 2017. (Link unavailable)

- Wikipedia. “Square and Compasses”. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Square_and_Compasses

- View of China blog. “Nuwa and Fuxi” article. 2019. (Link unavailable)

- Vectors of Mind blog. “Eve Theory of Consciousness v3.0”. 2024. (Link unavailable)