TL;DR

- Müller’s View: 19th-century philologist Max Müller saw Indo-European serpent myths (like Vṛtra) not as literal snakes but as allegories for natural forces (darkness, storm clouds), arising from language decay.

- Universality Questioned: While acknowledging the near-universal presence of serpent veneration, Müller rejected theories of a single, diffused global serpent cult, attributing similarities to independent psychological tendencies.

- Aryan Origins: Müller argued Vedic tradition had its own serpent beliefs (celestial/atmospheric enemies of light) that later developed into earthly snake propitiation, not solely borrowed from non-Aryans.

- Cross-Cultural Symbolism: Serpents widely symbolize rebirth/immortality (skin shedding), knowledge (Eden, Asclepius), fertility (earth/water connection), and the eternal cycle (Ouroboros), but interpretations vary dramatically (god vs. devil).

- Social Technology: Serpent cults function socially by establishing taboos (not killing snakes), strengthening group identity through rituals (Nag Panchami), creating social roles (priests/priestesses), and mediating morality.

- Deep Patterns & Contradictions: The serpent is a multivalent archetype embodying dualities (life/death, wisdom/deceit, chaos/order) and reflecting cultural anxieties and values.

Max Müller’s Philological Take on Nāga and Sarpa Worship#

Friedrich Max Müller, the 19th-century philologist and mythologist, approached serpent worship through the lens of language and comparative mythology. In his view, many ancient “serpents” in Indo-European lore were originally symbolic, not literal snakes.

For example, Müller observed that the Rigvedic ahi (“serpent”) Vṛtra – the dragon slain by Indra – represents the choking darkness or storm-cloud that holds back the life-giving waters.[^1] He stressed that such serpents in Vedic hymns “cannot be taken as real serpents; they can only be meant for the dangerous brood of the dark night or the black clouds”.1

In other words, the Sanskrit terms nāga (serpent being) or sarpa (snake) often referred to cosmic or meteorological forces in early poetry, rather than mere reptiles. Müller’s philological analysis thus cast serpent myths as nature-symbols – a poetic way to describe the encroaching night, drought, or storm that the solar gods had to overcome.

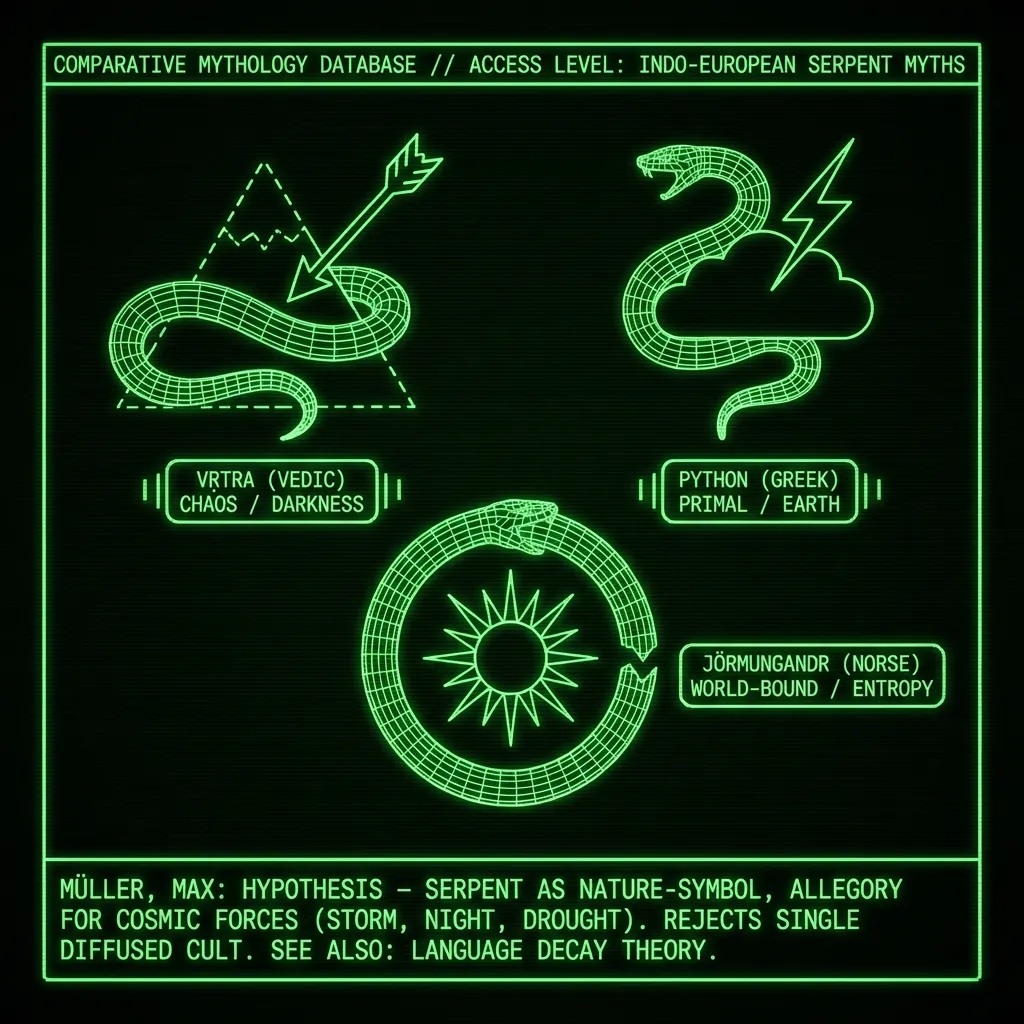

Müller extended this reasoning across Indo-European traditions. He noted the recurring myth of a hero or thunder-god versus a serpent/dragon (Indra vs. Vṛtra in the Veda, Apollo vs. Python at Delphi, Thor vs. Jörmungandr in Norse myth, etc.) and saw a common origin in ancient metaphors for natural phenomena.2

The serpent, in Müller’s interpretation, was typically the “enemy of light”, a demon of chaos or darkness to be trodden underfoot by the victorious sun or storm deity.3 This philological perspective aligns with Müller’s broader theory that many myths arose from decayed language – poetic descriptions of sunrises, storms, or nights which later generations took literally. Thus, he viewed early serpent legends as allegories: the coiling dragon was not a zoological snake but a linguistic metaphor for darkness, later misunderstood as a literal monster.

Serpent Veneration: A Universal Cult or Cultural Coincidence?#

Müller was well aware that serpents are worshipped or revered in many cultures worldwide – almost to the point of universality. (One contemporary scholar noted “the cult of the snake is widespread and is especially important in the Indian tradition,” appearing in everything from the Hebrew Bible (the Eden serpent) to the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh.4) However, Müller resisted any simplistic notion of a single “serpent cult” diffusing to all peoples. In Chips from a German Workshop (Vol. V), he explicitly criticized theories of a universal serpent-worship substratum linking disparate religions. For instance, he took issue with James Fergusson’s claim that both Scandinavian Odin-worship and Indian Buddhism grew from a common base of “Tree and Serpent Worship”.5 Müller quoted such assertions only to label them “unscientific” and misleading.6 He cautioned that superficial analogies (like seeing Buddha’s mother Māyā and Mercury’s mother Maia as proof of shared serpent lore, or finding “traces of serpent worship” in ancient Scotland as evidence of Buddhist influence) “cannot be allowed to pass uncontradicted”.7 In Müller’s estimation, human cultures may independently revere serpents without there being a single historical cult or migration behind it. In short, he acknowledged serpent veneration as nearly universal in distribution,8 but he attributed this to common psychological and symbolic tendencies rather than one global religion of the serpent.

Notably, Müller also nuanced the idea (held by some of his contemporaries) that serpent worship was entirely “un-Aryan.” Scholars like Fergusson had argued that Indo-Europeans (Aryans) originally had no snake cult at all – viewing it as a practice of “Turanian” or indigenous peoples which Aryans only adopted later.9 Müller partly disputed this. He conceded that the crude “ophiolatry” of African savages – literal worship of snakes as totems or fetishes – was foreign to early Aryans.10 But he also pointed out that belief in serpent powers did exist in Vedic tradition from the start, though in a different guise.11 The Vedic Indians spoke of divine or demonic serpents (e.g. the serpent Soma in the sky, or serpent adversaries of the Aśvins) long before any contact with aboriginal snake-worshipping tribes. Müller argued that “a belief in serpents had its origin in the Veda,” only initially those serpents were celestial or atmospheric, “enemies of the solar deities, and not yet the poisonous snakes of the earth”12 In later ages, this belief developed into more concrete snake propitiation rites – offerings to placate serpent spirits – a development he considered “thoroughly Aryan” and not necessitating outside influence.13 He even called it the “laziest of all expedients” to simply blame anything barbarous (like blood sacrifice or snake worship) in Indian religion on non-Aryan influences.14

In summary, Müller saw serpent veneration as a recurring phenomenon across cultures – a product of similar imaginative and religious impulses rather than a single theology. He treated it as practically universal in a comparative sense (from India to Greece to Africa, serpents loom large), but he rejected overly speculative theories that linked these practices genetically. Each culture’s serpent lore had to be studied in its own context, although underlying psychological themes might be shared.

Theology, Psychology, or Ecology? Müller’s Framing of Snake Worship#

Müller primarily framed serpent worship in mythological and psychological terms. As a scholar of comparative religion, he was less interested in ecological drivers (such as the physical prevalence of snakes in a region) and more in how the human mind mythologizes nature. His writings suggest that psychology and language were key: early humans everywhere felt both fear and awe toward the mysterious snake, and through language they imbued it with supernatural meaning. Theologically, Müller did not regard the serpent as a high deity in the “Aryan” sense of a sky-father or solar god; instead, snake cults were for him an example of “natural religion” – the worship of natural objects or animals – often linked to animism or fetishism. In his Lectures on the Science of Religion, Müller even mentions “the African faith, with its strange worship of snakes and stones,” contrasting it with the more abstract deities of Indo-Europeans.15 While he respected that all faiths have their inner coherence, he tended to class literal snake-worship as a more primitive, fear-based devotion, arising from psychological responses of awe, terror, or sexual fascination.

Crucially, Müller’s interpretation of serpent symbolism was naturalistic rather than moralistic. He did not frame serpent-veneration primarily in a theological sense (e.g. as a symbol of Satan or a savior across all cultures); instead, he viewed it as an outgrowth of how people personify natural forces and psychological states. A thunderstorm in the night becomes a dragon in myth; a healing spring guarded by snakes becomes a snake-god shrine; the terror of a venomous cobra yields a village snake cult for protection. In Müller’s analysis, the psychological motivation – whether fear of the snake’s danger, admiration for its grace and longevity, or the subconscious phallic/sexual awe it inspires – was central to why so many societies sanctified serpents.

It’s telling that Müller drew a line between the “Aryan” approach to serpent worship (metaphorical, sky-oriented, eventually philosophized) and the “savage” approach (literal idolization of actual snakes).16 This implies a kind of evolutionary psychology of religion: early Vedic people, he thought, spoke of serpents in a poetic/spiritual sense (a stage of mythic imagination), whereas later popular Hinduism or African animism might actually feed milk to cobras or keep pythons in temples (a stage of ritual appeasement, driven by more visceral psychology and local ecology). In the latter case, practical ecology and fear do play a role – e.g. in India and Africa people revering snakes likely because those animals could be deadly or beneficial in the environment. Müller acknowledged such practices (and did not deny that real cobras were being worshipped by his contemporaries in India), but he contextualized them as the “later development” of an idea, not its origin.17 Overall, his framing was that serpent worship began as mythology (an attempt to explain and symbolically master natural forces) and only secondarily became cultic practice (with psychological fear, propitiation, and perhaps ecological utility – like keeping snakes happy so they won’t bite the villagers – coming to the forefront).

In essence, Müller approached serpent worship as a crossroads of mythology and psychology: the serpent was a naturally potent symbol that different peoples elevated to the sacred, either as metaphorical “demons of darkness” or as literal holy animals, depending on their stage of religious thought. He gave far less emphasis to ecological or material factors, focusing instead on how language, symbolism, and the human mind’s reverence/fear of nature produced the cult of the serpent.

Cross-Cultural Serpent Symbolism in Premodern Traditions#

Across the world, serpents slither through the myths and rituals of premodern societies. Indeed, snake symbolism is so widespread that one scholar deemed it “nearly universal” among ancient religions.18 Cultures separated by vast oceans still converged on the serpent as a sacred, enigmatic figure – though the meaning of the serpent could vary dramatically. Below, we delve into a few geographic examples to trace common themes:

South Asia and Southeast Asia#

In India, the snake or Nāga enjoys deep reverence. Hindu mythology speaks of semi-divine serpent beings (Nāgas) who inhabit underworld rivers and guard treasures. The snake often represents rebirth, death, and mortality because it sheds its skin and emerges “reborn” – a potent symbol of renewal.19 Even in folk practice, serpents are honored: across India one finds shrines with carved cobras, and people make food offerings to these images. It’s taboo to kill a cobra; traditionally, if a cobra is accidentally killed it is cremated with full rites like a human funeral.20 Such veneration spread beyond India into Southeast Asia with the diffusion of Hindu-Buddhist culture. In Cambodian legend, for instance, the local Nāga princess Soma marries an Indian Brahmin, symbolizing the union of Indian immigrants with the indigenous serpent cult of the land.21 Even today, many Southeast Asian temples feature Nāga sculptures (multi-headed serpent deities) at their gates, and annual festivals like Nāga Panchami in India celebrate serpents with offerings of milk. The common thread is a view of snakes as guardians of life-giving waters, fertility, and wealth – and as beings to be propitiated for safety and prosperity.

Mesoamerica#

In ancient Mesoamerican civilizations, the serpent was elevated to one of the greatest of deities. The Aztecs, Maya, and their predecessors worshipped the Feathered Serpent – known as Quetzalcóatl in Nahuatl or Kukulkan in Mayan. This deity, depicted as a majestic snake adorned with quetzal feathers, embodied a fascinating dualism. As Müller might appreciate, it combined sky and earth: feathers signified its celestial, godly aspect while the serpent form signified its chthonic, earthly aspect.22 The Feathered Serpent was associated with creation, wind, fertility, and knowledge. At Teotihuacan (in modern Mexico), an entire pyramid (the Temple of the Feathered Serpent) was devoted to this god, its facade carved with rows of reptilian heads.23 In later Aztec lore, Quetzalcóatl was revered as the bringer of civilization – the god who gave humanity learning and the calendar. This benevolent image is strikingly different from the fearsome serpents of Indo-European myth. The Mesoamerican serpent, far from a demon, was often a civilizing hero or a creator figure. It shows how fluid serpent symbolism can be: here the snake was not primarily a symbol of death but of divine wisdom and fecundity.

Africa (Sub-Saharan)#

Across Africa, snakes have been worshipped in various forms, often linked to rainbows, rivers, and ancestral spirits. In West Africa, one famous example is the Vodun (Voodoo) serpent deity Dangbé (Dan) of Benin. In the city of Ouidah, a Temple of Pythons houses live royal pythons that are allowed to slither freely among devotees.24 Images of the rainbow-serpent Dan are plastered all over the city as tributes to this powerful god, who is regarded as a divine mediator between the spirit world and the living.25 The python is so sacred in this community that seeing a snake cross one’s path is considered excellent fortune, and the animals are handled with reverence rather than fear.26 These African serpent cults usually cast the snake as a benevolent protector and fertility spirit. In Benin, for example, the serpent symbolizes peace, prosperity, and wisdom, much as cattle are esteemed in India.27 Further east, other African traditions speak of a primordial Rainbow Serpent (for instance, in some Bantu and Khoisan myths) that encircles the world or brings the rains. Such myths closely connect the snake with life-giving water and the continuity of the tribe. Anthropologists note that in many African societies, specific snake species (like pythons) were taken as clan totems, never harmed and often fed or housed, reinforcing social bonds and a sense of kinship with nature.

Near East and Mediterranean#

The ancient Near East had its share of serpent cults and symbols, which later influenced Biblical and classical lore. In Mesopotamia, snakes were seen as symbols of immortality and hidden knowledge – thanks to their renewing molt. The Sumerians worshipped a serpent god of healing and fertility named Ningishzida, often depicted as a serpent entwined on a rod (a motif echoed later in the Greco-Roman caduceus symbol).28 Canaanite tribes venerated serpent figurines in the Bronze Age, and archaeologists have uncovered copper snake idols in ancient temples of Palestine.29 In Egypt, a cobra (the uraeus) adorned the pharaoh’s crown as a sign of divine kingship, and the goddess Wadjet was envisioned as a cobra guarding the land. Meanwhile, Greek religion remembered Python, the earth-dragon of Delphi, and the heroic feats of Heracles and Apollo in overcoming serpents. Interestingly, the Greeks also had positive serpent imagery: the god of medicine, Asclepius, carried a staff with a coiled serpent, and household gods were often represented by friendly snakes. The city of Athens kept a sacred serpent in the Erechtheion temple – associated with the hero-king Erechthonios – and if this snake refused its monthly food offering, it was seen as a grave omen for the city.30 Thus, in the Mediterranean world the serpent could be both guardian and adversary: a giver of oracles and cures, or a monstrous foe to be slain. This duality would later crystallize in the Judeo-Christian tradition as the opposition between the healing bronze serpent of Moses and the tempting serpent of Eden.

From these few examples, it’s clear that premodern societies invested serpents with rich meaning. Whether as creator, destroyer, protector, or trickster, the snake became a canvas for cultural values and fears. The diversity is striking: one culture’s revered rainbow python is another culture’s demonic dragon. Yet certain patterns (and even coincidences) emerge almost everywhere – suggesting why Müller and others felt a comparative approach was justified. Serpents are universally exceptional creatures (legless, slick, sometimes deadly, sometimes long-lived) and so readily lent themselves to symbolic use. We consistently see snakes linked to water, earth, and fertility (they frequent holes in the earth and waterbeds), as well as to renewal (shedding skin), wisdom (silent observation, elusive movement), and danger (venom, strangulation). These inherent traits of real snakes get amplified into the supernatural domain in myth.

Serpent Worship as Social Technology#

Beyond their symbolic import, serpent cults have also functioned as a kind of “social technology” – shaping norms and regulating community behavior. The worship of a snake can serve very practical social purposes under the cloak of religion. One obvious function is the inculcation of taboos and ethical norms: for instance, in regions where snake worship took hold, it often became a taboo to kill snakes (especially the revered species). We saw this in India, where harming a cobra is forbidden and even accidental deaths are atoned by funerary rites.31 Such a norm not only protects a feared creature but also channels human aggression – people are taught to conquer their fear and respect the animal, rather than attack it. In effect, the serpent cult encodes a form of non-violence (at least toward the sacred animal), which can have ecological benefits (preserving species that control pests) and moral benefits (promoting reverence for life). Similarly, in Ouidah, Benin, the python god Dan’s worship means pythons slither harmlessly in households and are gently returned to the temple if found – a remarkable example of a normally fearsome creature coexisting with humans due to religious respect.32 The community rallies around the belief that the snakes bring good fortune and must not be harmed, which cultivates social harmony (no quarrels over snake encounters) and a shared sense of blessedness when a snake crosses one’s path.33

Serpent worship often involves rituals and festivals that strengthen group identity. Many cultures have annual snake festivals (for example, the Indian Nag Panchami where sisters pray to serpent deities for their brothers’ well-being, or the West African Vodun ceremonies where the python is paraded and honored). These gatherings act as social glue: people come together in a common reverence, temporarily setting aside interpersonal conflicts in the face of the sacred. The rituals can be elaborate – dancing with live snakes, making offerings of milk, eggs, or alcohol to snake shrines, and carrying images of serpents in processions.34 By requiring coordination and emotional investment, such practices help regulate community behavior and channel emotions. Aggression and fear, in particular, are transformed into controlled expressions. Instead of villagers fearfully hunting a snake in panic, they ritually “feed” it and sing songs to appease it. The dangerous energy of the serpent is thus domesticated within a cultural framework. In psychological terms, one might say the community projects its anxieties onto the serpent and then resolves them through ritual – a kind of catharsis or safety valve for aggression. For example, if a drought or illness strikes, rather than turning on each other, a community might blame angry serpent spirits and collectively perform appeasement rites, thereby preserving internal unity.

Serpent cults also often entail social roles that structure behavior. In many traditions, only certain people (priests, priestesses, or shamans) can handle or interpret the will of the sacred snakes. This creates an accepted social hierarchy and division of labor. The priestess of the snake – such as the celibate women who carry serpent idols in parts of India35 or the Vodun priest in Benin who tends the pythons – holds a respected position, which can elevate the status of women or particular clans. Through the figure of the snake guardian, societies impart values: courage (in handling snakes), purity (often snake priests observe dietary or sexual abstinence rules), and wisdom (knowing the “language” or movements of the serpent is akin to divination). Even myths play a regulatory role: a famous Greek oracle, for instance, was the Oracle of Delphi, reportedly founded after Apollo slew the serpent Python. Yet the priestess of Delphi (the Pythia) incorporated the serpent’s power – she delivered oracles in a trance believed to be inspired by the earth-serpent. This myth and ritual told ancient Greeks that even the god’s power came with the absorption of the serpent’s spirit, indirectly reinforcing the authority of the (human) priestess and the practice of oracular trance.

In these ways, serpent worship acts as a social institution that encodes knowledge and norms. It can teach a community how to interact with their environment (e.g. do not kill the sacred snakes that protect our crops from rats), and how to sublimate certain impulses (fear, violence) into reverence and communal celebration. The snake, often hovering between world of humans and spirits, also serves as a moral mediator: many folk tales warn that harming a snake will anger the gods, whereas caring for one may be rewarded (for example, Indian lore of a farmer who shelters a cobra and finds his barn blessed with prosperity). Such stories promote ethical behavior not through abstract principles but through concrete, emotionally resonant symbols – the snake will remember and punish or reward you. In a sense, the serpent becomes an ever-watchful totem enforcing community standards.

Mythological, Anthropological, and Semiotic Insights: Deep Patterns and Contradictions#

When we assemble the many threads of serpent symbolism, certain deep patterns come to light – as do striking contradictions. Mythologically, snakes nearly everywhere evoke the cyclical rhythms of nature and life. They are emblematic of rebirth and immortality (thanks to shedding skin and seemingly “renewing” themselves) and thus often appear guarding the secrets of eternal life. In Mesopotamia’s Epic of Gilgamesh, a serpent famously steals the herb of immortality from the hero and promptly rejuvenates, linking snakes to longevity and renewal.36 Likewise, the serpent in Eden offers knowledge of good and evil – a kind of intellectual rebirth for humanity – though with a fatal cost. This leads to another pattern: serpents as keepers of knowledge. Whether it’s the cosmic wisdom of the Mesoamerican Quetzalcoatl, the medical knowledge of Asclepius’s serpent, or the cunning of the biblical serpent, these creatures are often credited with secret knowledge or oracular truth. Semiotically, one can argue the snake’s habit of lurking in cracks and crevices, suddenly appearing and vanishing, made it a perfect symbol for hidden wisdom and mystery.

Another near-universal motif is the snake as a fertility symbol. As Ninian Smart observes, the serpent often has a dual fertility aspect – partly due to its phallic shape and partly because it lives in the “life-giving earth” (soil, caves, under stones).37 Fertility goddesses from the Mediterranean to India are frequently accompanied by snakes. In ancient Crete, for example, figurines of the Minoan Snake Goddess (bare-breasted, holding a snake in each hand) likely represent dominion over renewal and the household’s fertility. In India, serpents are associated with rain and harvest – the Nagas bring the monsoon rains – and with procreation (many couples pray to snake deities for children). The semiotic linkage of snake = phallus = fertility is quite direct in some cultures,38 but in others it is the snake’s connection to water that makes it a fertility guarantor (water being the seed of the earth). Notably, even the negative serpent in Genesis is entwined with fertility – the story immediately follows with Eve’s punishment of pain in childbirth, connecting the serpent to human reproduction in an adversarial way.

Perhaps the most profound symbolic pattern is the serpent as a symbol of the eternal cycle. The image of Ouroboros, the snake swallowing its own tail, appears in many traditions (from ancient Egypt to alchemical manuscripts) and encapsulates the idea of unity of beginning and end, creation and destruction.39 The world-encircling serpent (whether it be the Norse Jörmungandr or the Hindu Śeṣa on whom Vishnu rests) likewise conveys the notion that existence is encircled – and periodically renewed – by the cosmic serpent. This can be a positive symbol of wholeness and infinity, but also a reminder of time’s devouring nature (as the tail-devouring serpent can imply self-destruction in the cycle of life and death). In a way, the ever-recurrent snake mirrors the seasonal cycle: it hibernates and emerges, “dies” and is reborn, mirroring the agricultural dying and rebirth of the land.

With these patterns, however, come stark contradictions in how cultures interpret the serpent. One culture’s revered creator is another’s devil. Nowhere is this more evident than in the contrast between, say, West African or Native American positive serpent lore and the Judeo-Christian demonization of the snake. In the Bible, the serpent in Eden is cursed above all creatures for leading humans astray, becoming the archetype of Satan – deceitful and evil. Yet gnostic sects later flipped this view, exalting the serpent as the bringer of gnosis (knowledge) against an oppressive deity. This diametric opposition – wisdom-giver vs. deceiver – shows the extreme malleability of the snake’s signification. Even within a single culture, the snake’s role can flip. The Hebrew tradition provides a great example: the bronze serpent (Nehushtan) made by Moses in the wilderness was originally a divine instrument of healing, yet later Hebrew reformers, like King Hezekiah, smashed it when people started worshipping it as an idol.40 The snake went from symbol of God’s mercy to “abomination” in the span of a few centuries, reflecting a theological swing. In Greek mythology, too, we have benevolent snakes (the friendly household Agathos Daimon or Zeus Meilichios depicted as serpents) and malevolent dragons (like Typhon or the Hydra). This dual nature of serpents – at once life-giving and life-threatening – may be inherent to their symbolism. They reside in liminal spaces (water’s edge, boundary of villages, threshold of the underworld), so they easily slip between categories: good/evil, male/female, chaos/order.

Anthropologically, some have suggested that where snake cults were part of older, earth-centered “matriarchal” religions, later patriarchal systems demonized them (hence the hypothesis that Eve’s serpent was a symbol of earlier goddess worship, cast as a villain by a new order). Whether or not this is true, it is fascinating that snake iconography so often aligns with goddesses and earth cults (from the Greek Athena and her snake companions, to the Indian Nagini goddesses like Manasā, to the female mediums of Python spirit in West Africa) – hinting at a link between serpents and the feminine divine. In contrast, male sky-gods often battle serpents (Zeus vs Typhon, Indra vs Vṛtra, Marduk vs Tiamat). This could be read as a mythic reflection of two principles in tension: the celestial vs the chthonic. The semiotic richness of the serpent is that it can symbolize either side or even the unity of both (as Quetzalcoatl’s feathers and scales show).

The contradictions in serpent symbolism also extend to its use as a social symbol. A snake can be a totem of group identity, but also a marker of the “other”. For example, ancient Egyptians used the rearing cobra (uraeus) to signify royalty and divine authority, yet in Hebrew texts, Egypt’s power is sometimes denigrated as a serpent or dragon to be slain by Yahweh. In medieval and early modern European folklore, the positive ancient motifs were mostly lost, and the snake became associated with witches, heretics, and dark arts – essentially an anti-social symbol to be feared or eradicated. Meanwhile, far across the world, Australian Aboriginal cultures maintained their reverence for the Rainbow Serpent as the font of creation and law, a being that established social order. It’s intriguing that a single symbol can either uphold social norms or represent their subversion, depending on context.

What emerges from this global survey is a picture of the serpent as a multivalent sign – arguably one of humanity’s most enduring and provocative. Its scaliness reflects both the glitter of divinity and the slime of evil in our imaginations. As a semiotic object, the snake is extraordinarily plastic: it signifies fertility, wisdom, cyclical time, danger, death, regeneration, infinity – sometimes all at once. This may be why Müller and his contemporaries were so captivated by serpent myths; they offer a case study in how different cultures draw different messages from the same natural archetype.

In modern terms, we might say the serpent is an archetype that taps into the collective unconscious – a Jungian might point to the Kundalini serpent power in Hindu yoga as symbolizing the transformative life force coiled at the base of the spine, waiting to ascend. Indeed, the Kundalini serpent in esoteric yoga is a positive inner energy, showing again the theme of transformation and enlightenment associated with snakes. Whether we examine ancient ritual or depth psychology, the snake tends to represent something fundamental: the cycle of life and death, the knowledge of beyond, and the powers of the natural world that humans both rely on and fear.

Max Müller, with his focus on philological roots, saw one layer of this truth: that behind many snake legends was a human grappling with nature’s rhythms (day and night, storm and sunlight). Subsequent anthropology and semiotics have uncovered additional layers – how snake worship can organize a society, or how the snake embodies polarities that societies negotiate in myth. The patterns we surface (snake = life-death-rebirth, snake = knowledge, snake = fertility) appear in culture after culture, suggesting a shared human fascination. Yet the contradictions (snake as revered god vs. cursed devil, snake as healer vs. destroyer) remind us that symbols are ultimately given meaning by people in context.

In the end, the cult of the serpent tells a story not just of snakes, but of ourselves. It is a mirror of the human psyche and social order. Müller treated serpent mythology as a significant piece of the puzzle in the “science of religion,” and our deeper explorations confirm that the Serpent is a truly cross-cultural code – one that encodes primal fears, ecological wisdom, sexual potency, and spiritual renewal all at once. It is little wonder that from the Nāga sanctuaries of India to the feathered serpent temples of Mexico, from healer’s staff to royal diadem, the image of the snake has coiled itself around the collective heart of humanity, leaving an indelible imprint on our religions and rites.

FAQ #

Q 1. How did Max Müller interpret serpent myths? A. Müller primarily saw them through a philological lens as decayed language – original metaphors for natural phenomena (like storms or night) that later generations misunderstood as literal monster myths. He viewed serpents like the Vedic Vṛtra as allegories for darkness or drought overcome by solar deities.

Q 2. Did Müller believe in a single, universal serpent cult? A. No. While acknowledging widespread serpent veneration, he criticized theories of a single origin or diffusion. He argued that similar psychological responses to snakes and common linguistic processes could lead to independent development of serpent reverence in different cultures.

Q 3. What are the most common symbolic meanings of serpents across cultures? A. Common themes include rebirth/immortality (shedding skin), fertility (earth/water connection, phallic shape), hidden knowledge/wisdom, guardianship (of treasures, water sources), danger, and the cyclical nature of time (Ouroboros).

Q 4. How does serpent worship function as a social technology? A. It can establish taboos (e.g., against killing snakes), foster group identity through shared rituals and festivals, create specific social roles (priests/priestesses), regulate aggression and fear, and enforce moral norms through myths and folklore.

Q 5. Why is serpent symbolism often contradictory (e.g., good vs. evil)? A. The serpent’s inherent ambiguity (living between worlds, being dangerous yet regenerative) makes it a potent symbol for embodying dualities. Cultural contexts heavily shape interpretation, leading to depictions ranging from creator gods (Quetzalcoatl) to demonic figures (Satan).

Footnotes#

Sources#

- Alexander, Kevin. “In Benin, up close with a serpent deity, a Temple of Pythons and Vodun priests.” The Washington Post, January 26, 2017. Link

- Bhattacharyya, P.K. The Indian Serpent Lore. 1965. (Mentioned as ethnographic source in original text).

- Goldziher, Ignaz. Mythology Among the Hebrews. 1877. Gutenberg Link

- Moorehead, W.G. “Universality of Serpent-Worship.” The Old Testament Student 4, no. 5 (1885): 205–210.

- Müller, F. Max. Chips from a German Workshop, Vol. V. London, 1881. Gutenberg Link

- Müller, F. Max. Contributions to the Science of Mythology, Vol. II. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1897. Archive.org Link

- Smart, Ninian. “Snake Worship.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 1999 revision. (Often references Wikipedia in original text, likely based on this).

- Wake, C. Staniland. Serpent-Worship and Other Essays. London: George Redway, 1888. Gutenberg Link

- Wikipedia contributors. “Feathered Serpent.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Link

- Wikipedia contributors. “Ouroboros.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Link (Note: Original text links Britannica, but Wikipedia covers similar ground).

- Wikipedia contributors. “Snake worship.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Link

F. Max Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology (1897), vol. II. Link ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology (1897), vol. II. Link 1, Link 2 ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology (1897), vol. II. Link 1, Link 2 ↩︎

Ninian Smart, “Snake Worship,” Encyclopedia Britannica (1999). Also see general article on Snake worship - Wikipedia. ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Chips From A German Workshop, Vol. V (1881). Link ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Chips From A German Workshop, Vol. V (1881). Link ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Chips From A German Workshop, Vol. V (1881). Link ↩︎

See overview in Snake worship - Wikipedia. ↩︎

C. Staniland Wake, Serpent Worship and Other Essays (1888). Link 1, Link 2 ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology (1897), vol. II, p. 598. Link ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology (1897), vol. II, p. 598-599. Link ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology (1897), vol. II, p. 599. Link ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology (1897), vol. II, p. 599. Link ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology (1897), vol. II, p. 599. Link ↩︎

Reference likely to Lectures on the Science of Religion (1872), but corroborated by similar sentiments in Contributions to the Science of Mythology (1897), vol. II, pp. 598-599. Link 1, Link 2 ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology (1897), vol. II, p. 598. Link ↩︎

F. Max Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology (1897), vol. II, p. 599. Link ↩︎

Ninian Smart, “Snake Worship,” Encyclopedia Britannica (1999). Also see Snake worship - Wikipedia. ↩︎

See Feathered Serpent - Wikipedia and File:Facade of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent (Teotihuacán).jpg - Wikipedia. ↩︎

Kevin Alexander, “In Benin, up close with a serpent deity…” Washington Post (Jan 26, 2017). Link ↩︎

W.G. Moorehead, “Universality of Serpent-Worship,” The Old Testament Student 4, no.5 (1885), pp.205–210. Also see Snake worship - Wikipedia), noting archaeological finds of serpent cult objects in Canaan (Snake worship - Wikipedia). ↩︎

C. Staniland Wake, Serpent Worship and Other Essays (1888). Link ↩︎

Ninian Smart, “Snake Worship,” Encyclopedia Britannica (1999). See also Snake worship - Wikipedia. ↩︎

Ninian Smart, “Snake Worship,” Encyclopedia Britannica (1999). See also Snake worship - Wikipedia. ↩︎

See “Ouroboros | Mythology, Alchemy, Symbolism” - Britannica. ↩︎

C. Staniland Wake, Serpent Worship and Other Essays (1888). Link ↩︎