TL;DR

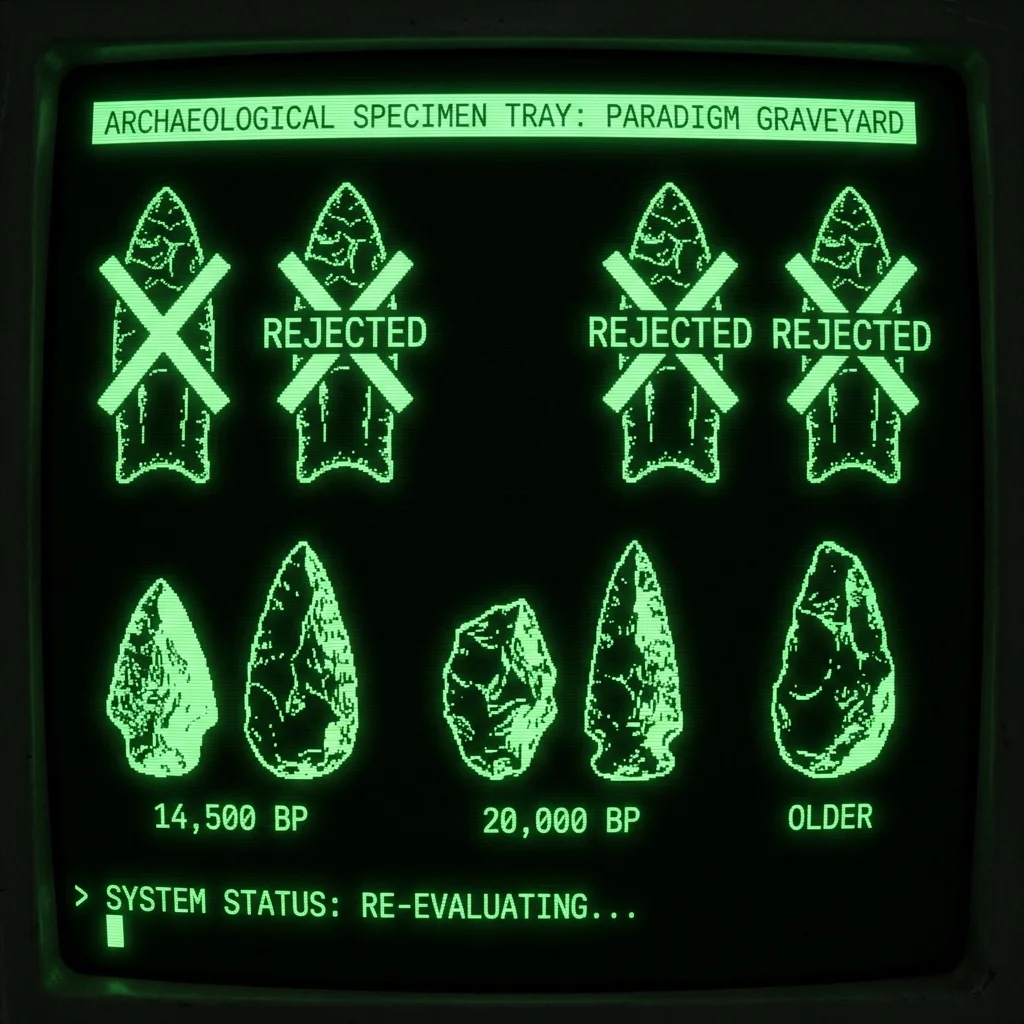

- Mid-century “pre-Clovis” claims (Sandia, Tule Springs, Lewisville, Sheguiandah, Old Crow, Calico, Hueyatlaco, Pikimachay, Pedra Furada, Yuha, etc.) mostly collapsed under better stratigraphy, taphonomy, and geochronology. See syntheses by Waters & Stafford (2007) and Goebel et al. (2008); Meltzer (2009).

- Recurrent failure modes: mixed or reworked deposits, “geofacts,” contaminated charcoal/bone, shaky typology, and publication bypasses.

- The field’s “immune system” hardened Clovis-first not from dogma alone but because the data were bad—until a few sites (Meadowcroft, Monte Verde) met modern standards and a broader evidence base (genetics, paleoecology) converged. Meadowcroft research; Dillehay et al. (2008); Rasmussen et al. (2014).

- Post-1990 breakthroughs (e.g., Buttermilk Creek; White Sands footprints) clinched an earlier peopling timeline and showed why the discipline was rightly cautious for decades. Jenks (2010); Waters et al. (2011); Holliday et al. (2011).

“The great tragedy of science—the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact.”

— T. H. Huxley

The case files: mid-century claims that didn’t stick#

Archaeology’s 20th-century pre-Clovis hunt produced a rogues’ gallery of sites. Below I reconstruct what was claimed, what the data really showed, and why the claims failed—with an eye to patterns that explain Clovis-first’s stickiness.

Sandia Cave (New Mexico)#

Claim. In the 1930s–40s, Frank Hibben reported “Sandia points” beneath Folsom and extinct fauna—older than Clovis. Evidence. Stratigraphic sequence with ochre layer; artifacts below faunal remains in the classic narrative. Problems. Inconsistent stratigraphy; missing or ambiguous provenience; later allegations of salting and irregular methods. The best single account of the controversy is Douglas Preston’s reported piece, “The Mystery of Sandia Cave” (1995), alongside later summaries. Status: not accepted as pre-Clovis. Preston (1995); Sandia Cave Wikipedia.

Tule Springs “Big Dig” (Nevada)#

Claim. Massive 1962–63 excavations sought human–megafauna association in Pleistocene Las Vegas Formation. Evidence. Deep trenching, black-mat stratigraphy, obsidian flake in Pleistocene context. Problems. No secure artifacts in primary context; subsequent stratigraphic revisions. See the NPS overview of the Big Dig and Haynes’s USGS stratigraphic work. Status: no accepted pre-Clovis occupation demonstrated. NPS Big Dig Report; Haynes (1965).

Lewisville (Texas)#

Claim. Hearths and tools ≳37 ka; newspapers trumpeted “Texas Man.” Evidence. Charcoal and lithics in Trinity River terraces. Problems. Reworked charcoal, equivocal contexts; later work down-dated or rejected the Pleistocene ages. See Texas State Historical Association’s summary. Status: not pre-Clovis. Johnson (1987).

Sheguiandah (Manitoulin Island, Ontario)#

Claim. Thomas E. Lee argued Paleoindian+ levels in till‐like deposits, possibly very old. Evidence. Stratified lithics; early reports implied great age. Problems. Glacial/disturbed contexts; later syntheses place key materials as Holocene or ambiguous. See the monograph The Sheguiandah Site (2002). Status: not accepted as pre-Clovis. [^oai1]

Old Crow Basin (Yukon)#

Claim. “Worked” Pleistocene bones (including a caribou flesher) implying very early human presence. Evidence. Bone fracture patterns; typological identifications. Problems. Taphonomic ambiguity; key “artifact” redated with AMS to late Holocene (~1.26 ka), obliterating the Pleistocene claim. See the Alaska Journal of Anthropology update on the Old Crow flesher redating. Status: claim collapsed. 1

Calico Early Man Site (California)#

Claim. Louis Leakey (1960s) argued “artifacts” in deposits ≳100 ka. Evidence. Vast collections of chipped stones. Problems. “Geofacts” produced by natural processes; no secure refitting sequences; sediment ages precede Homo sapiens in the Americas by orders of magnitude. For a concise controversy history (and classic critiques such as Haynes 1973), see Dempsey’s SCA Proceedings paper, “Calico: The Lightning Spall Site”. Status: not archaeological. 2

Hueyatlaco / Valsequillo (Puebla, Mexico)#

Claim. Stone tools in deposits U-series-dated to ≥250 ka (!). Evidence. Reported artifact assemblages; radiometric ages on sediments/tephra. Problems. Severe stratigraphic/geomorphic discordances; dates apply to beds, not tool emplacement; no coherent cultural package. See overview in S. González et al., 2006. Status: overwhelmingly rejected. 3

Pikimachay (Ayacucho, Peru)#

Claim. MacNeish proposed occupations back to ≥20 ka; critics called the oldest “tools” geofacts. Evidence. Lithics and bones from strata h–k. Problems. Mixed assemblages, natural fracturing; recent re-assessments cautiously accept human modification mainly for younger Late Pleistocene/Holocene levels and not the most extravagant ages. See the new taphonomic study in BMSAP (2018). Status: early claims trimmed; late-Pleistocene horizons plausible, the rest doubtful. 4

Pedra Furada / Serra da Capivara (Piauí, Brazil)#

Claim. Rock-shelter complexes with hearths/lithics back to 30–50 ka. Evidence. Charcoal, burned features, pebble tools. Problems. Natural fires, geofacts, and site formation complicate claims; later work proposes Pleistocene sequences with artifacts, but skepticism persists. For pro and con, see Boëda et al. (2014) on Vale da Pedra Furada and Parenti (2023) reappraisal. Status: still contested; not decisive for pre-LGM peopling. 5 6

“Pleistocene” skeletons (California: Yuha, Del Mar, Sunnyvale, etc.)#

Claim. Human remains dated (by early methods) to late Pleistocene. Evidence. Conventional ^14C, amino-acid racemization, U-series. Problems. Contamination and method limits; AMS ^14C on collagen showed Holocene ages. See Stafford et al., Nature (1984) on the Yuha burial; see also U-series and AMS correctives for Del Mar/Sunnyvale. Status: not Pleistocene. 7 8

Comparative snapshot#

| Site (country/state) | Claimed age (mid-century) | Main evidence | Principal failure mode | Current status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandia Cave (US-NM) | ≥25 ka | Stratigraphic “Sandia points” | Stratigraphic ambiguity; allegations of salting | Rejected as pre-Clovis 9 |

| Tule Springs (US-NV) | ≥Pleistocene | “Big Dig” trenches, black mat | No secure human context | Not pre-Clovis 10 |

| Lewisville (US-TX) | ≥37 ka | Hearths + lithics | Reworked/taphonomically messy charcoal | Rejected as pre-Clovis 11 |

| Sheguiandah (CAN-ON) | Paleoindian–older | Lithics in till-like deposits | Glacial disturbance; mixed contexts | Not pre-Clovis [^oai1] |

| Old Crow (CAN-YT) | Pleistocene | “Worked” bones | Misidentified; AMS redating | Collapsed (late Holocene) 1 |

| Calico (US-CA) | ≥100 ka | Chipped stones | Geofacts; impossible ages | Rejected 2 |

| Hueyatlaco (MX-PUE) | ≥250 ka | Tools + U-series ages | Bed ages ≠ artifact ages; stratigraphic chaos | Rejected 3 |

| Pikimachay (PE-AYA) | 14–25 ka (older alleged) | Lithics + bones | Natural fracture; mixed deposits | Trimmed to younger horizons 4 |

| Pedra Furada (BR-PIA) | 30–50 ka | Charcoal, pebbles | Natural fires/geofacts | Contested; not consensus pre-LGM 5 6 |

| Yuha/Del Mar/Sunnyvale (US-CA) | 20–70 ka | Human bone | Contamination; AAR issues | AMS: Holocene 7 8 |

Why these claims failed (and Clovis-first hardened)#

Stratigraphy and site formation. Many “lower-than-Clovis” levels were palimpsests—deflated pavements, colluvial lags, or gully fills. Without microstratigraphy, refits, and sealed features, any lithic below Clovis looks older by default. (Compare the trench-wall fetish of the 1960s with today’s thin-section micromorphology and OSL suites.) Meltzer’s historiography remains essential: “Why Don’t We Know When the First People Came to North America?” (American Antiquity, 1989), and his book First Peoples in a New World. 12 13

Geofacts and typological wish-casting. Calico taught the field how enthusiastically nature flintknaps. Experimental trampling, lightning spalls, and mechanical breakage produced Calico-like “cores” and “flakes”—with no refitting chaîne opératoire. Dempsey’s review traces this arc succinctly. 2

Bad clocks. Early amino-acid racemization and conventional ^14C on contaminated collagen/charcoal produced spurious “Pleistocene” ages. AMS ^14C on clean fractions—and independent U-series—torpedoed the classic California skeletons and Yuha. See Stafford et al., Nature (1984); Bischoff et al., Science (1981). 7 8

Publication and rhetoric. Several claims first surfaced in press conferences, popular magazines, or institutional gray literature, with data dribbling out piecemeal—leaving critics to do the synthesis (and the damage). Meltzer’s 1989 essay documents the sociology of how these debates were waged. 12

Disciplinary immune response. After serial false positives, the bar rose (appropriately): sealed contexts; clear human agency (refits, reduction sequences, bone/plant use-wear, features); coherent geochronology with converging methods; and peer-auditable archives. The “Clovis-first” consensus persisted because most counter-examples were weak on these counts, not because archaeologists couldn’t imagine an earlier peopling. For synthesis, see Goebel, Waters & O’Rourke (2008). 14

What finally cracked it

Meadowcroft and Monte Verde: method not myth#

Meadowcroft Rockshelter (Pennsylvania). Dated components extending to ~16 ka (cal BP), intact microstratigraphy, careful decontamination of bituminous contaminants, and a patient, decades-long defense in the journals. See Adovasio et al., “Two Decades of Debate” (archival PDF). Status: widely accepted as pre-Clovis. 15

Monte Verde II (Chile). Organic-rich, waterlogged preservation—structures, perishable artifacts, seaweeds—plus stratigraphic sealing and a 1997 “jury visit” that convinced skeptics; more recent work tightens the sealing age to ~14,550 cal BP. See Pino et al., Antiquity (2023) and Dillehay et al., PLOS One (2015). 16 17

The 2010s: scale and convergence#

Buttermilk Creek / Debra L. Friedkin (Texas). A large pre-Clovis lithic assemblage (15.5–13.2 ka) underlies Clovis, with optically stimulated luminescence dating and stratigraphic integrity. See Waters et al., Science (2011). 18

White Sands Footprints (New Mexico). Human trackways interbedded with lake sediments dated by multiple methods (including radiocarbon on Ruppia seeds cross-checked with alternative fractions) to ~23–21 ka; follow-up work addressed reservoir effects. See Bennett et al., Science (2021) and Dempsey et al., Nat. Ecol. Evol. (2023). 19 20

Big-picture synthesis. As radiocarbon protocols matured and sites stacked up, Clovis narrowed to ~13.1–12.6 ka, no longer “first.” See Waters & Stafford (2007) and the broader review in Goebel et al. (2008). 21

Lessons learned (so we don’t repeat the 1950s)#

- Context over objects. A beautiful biface in garbage stratigraphy proves nothing. Secure sealing, refits, and micromorphology beat typology every time.

- Multiple, independent clocks. AMS ^14C on chemically isolated fractions, U-series where appropriate, and OSL/IRSL for sediments—preferably converging.

- Define human agency positively. Reduction sequences, use-wear with confident function, features (hearths, posts), and activity areas; beware geofacts and natural burn signatures.

- Publish complete datasets. Let critics replicate your stats and your stratigraphy. The sites that survived (Meadowcroft, Monte Verde) did exactly that.

FAQ#

Q1. So does any mid-century “pre-Clovis” claim now stand? A. Essentially no. A few regions (e.g., Serra da Capivara; parts of Peru) continue to publish Pleistocene horizons, but the most famous mid-century claims (Sandia, Calico, Hueyatlaco, Lewisville) remain unaccepted as pre-Clovis because the contexts fail modern standards. 2

Q2. What about really early (>20 ka) occupation? A. White Sands footprints provide strong human presence ~23–21 ka; earlier claims require Monte-Verde-level context and convergent dating to persuade most archaeologists. 19 20

Q3. Did “Clovis-first” persist mainly for ideological reasons? A. Ideology colored rhetoric, but method explains most of it: after serial false positives, the bar rose. When sites met that bar (Meadowcroft, Monte Verde) and independent data converged, the model shifted. See Meltzer (1989; 2009) and Goebel et al. (2008). 12 13 14

Q4. What’s the canonical age range for Clovis itself? A. Roughly ~13.1–12.6 ka (cal BP), based on a vetted set of radiocarbon dates. See Waters & Stafford (2007). 21

Q5. Which single diagnostic should make us least gullible next time? A. Refitting reduction sequences across sealed microstrata, with orthogonal dating—because nature doesn’t knap cores in order and tuck them under a hearth.

Footnotes#

Sources#

- Adovasio, J. et al. “Two Decades of Debate on Meadowcroft Rockshelter.” (archival PDF) Science & Archaeology review (n.d.). Archive.org link.

- Bennett, M. R., et al. “Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum.” Science 374 (2021): eabg7586. article. 19

- Bischoff, J. L., et al. “Uranium series dating of human skeletal remains from the Del Mar and Sunnyvale sites, California.” Science 213 (1981): 1003–1005. USGS entry. 8

- Dempsey, D. “Calico: The Lightning Spall Site.” SCA Proceedings 22 (2009). PDF. 2

- Dillehay, T. D., et al. “New archaeological evidence for an early human presence at Monte Verde, Chile.” PLOS One 10 (2015): e0141923. open access. 17

- Dillehay, T. D. “Monte Verde: Seaweed, Food, Medicine, and the Peopling of South America.” Science 320 (2008): 784–786. (Contextual) ResearchGate entry. 22

- Goebel, T., Waters, M. R., O’Rourke, D. H. “The late Pleistocene dispersal of modern humans in the Americas.” Science 319 (2008): 1497–1502. PubMed. 14

- González, S., et al. “Valsequillo (Hueyatlaco) Pleistocene archaeology and dating.” World Archaeology 38 (2006): 611–627. T&F abstract. 3

- Meltzer, D. J. “Why Don’t We Know When the First People Came to North America?” American Antiquity 54 (1989): 471–490. Cambridge abstract. 12

- Meltzer, D. J. First Peoples in a New World (2nd ed.). Univ. of California Press, 2009/2021. publisher. 13

- National Park Service. “The Geology and Paleontology of Tule Springs Fossil Beds.” Fact Sheet (2018). PDF. 10

- Pino, M., et al. “Monte Verde II: an assessment of new radiocarbon dates and their sedimentological context.” Antiquity 97 (2023). article. 16

- Preston, D. “The Mystery of Sandia Cave.” The New Yorker (June 12, 1995). article. 9

- Stafford, T. W., et al. “Holocene age of the Yuha burial: direct radiocarbon determinations by accelerator mass spectrometry.” Nature 308 (1984): 446–447. PubMed. 7

- Texas State Historical Association. “Lewisville Site.” entry. 11

- Waters, M. R., Stafford, T. “Redefining the Age of Clovis.” Science 315 (2007): 1122–1126. Science. 21

- Waters, M. R., et al. “The Buttermilk Creek Complex and the Origins of Clovis at the Debra L. Friedkin Site, Texas.” Science 331 (2011): 1599–1603. PubMed. 18

- White Sands follow-up: Dempsey, M., et al. “Age of the human footprints from White Sands National Park, New Mexico.” Nat. Ecol. Evol. (2023). article. 20

- Julig, P. J. (ed.). The Sheguiandah Site: Archaeology and History of a Manitoulin Island Locality. (Mercury Series). 2002. open access listing. [^oai1]

- Haynes, C. V. “Quaternary geology of the Tule Springs area, Clark County, Nevada.” USGS Prof. Paper (1965). PDF. 23

- Krasinski, K., Haynes, C. V. “Old Crow Caribou Flesher Redating.” Alaska Journal of Anthropology (2010). PDF. 1