TL;DR

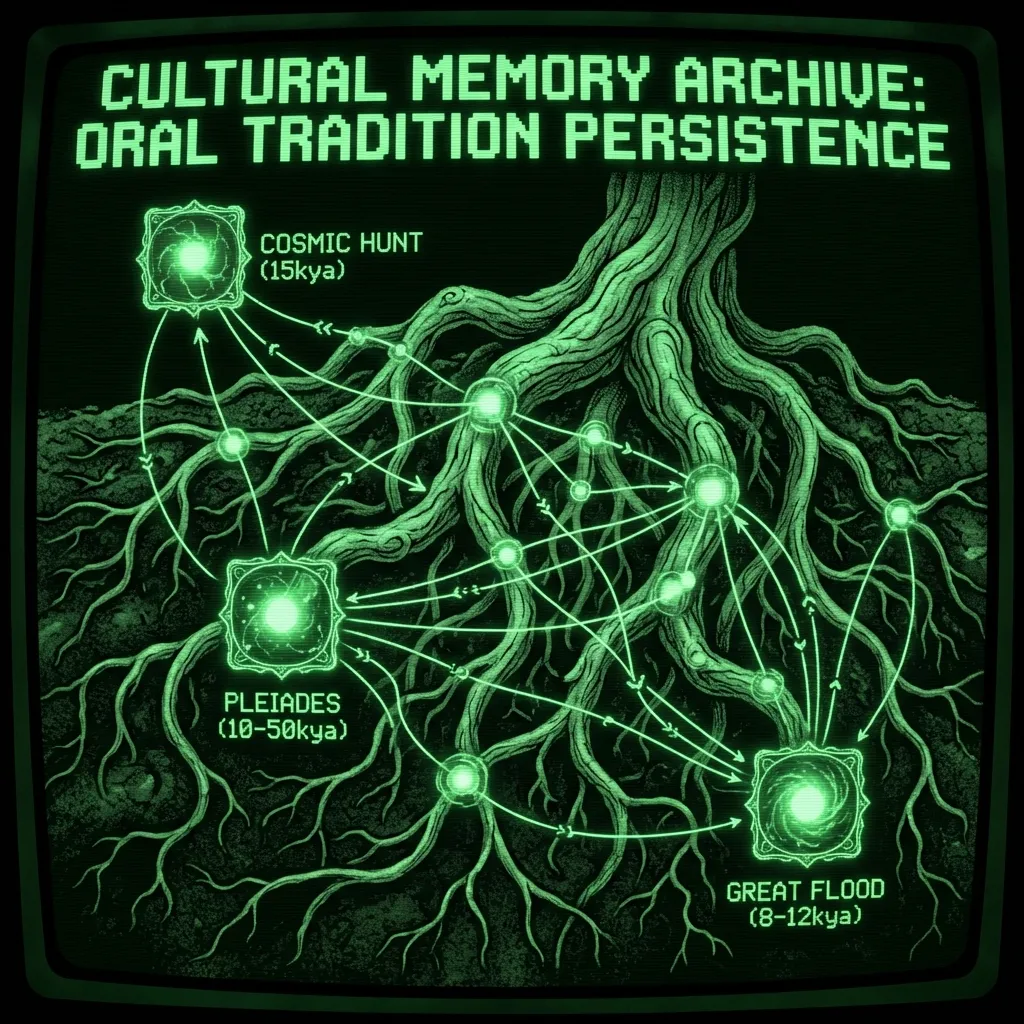

- Multiple myths worldwide likely originated over 8,000 years ago, surviving through oral tradition.

- Evidence comes from comparative mythology (shared motifs like the “Cosmic Hunt” ≈15kya), geomythology (myths matching dated geological events like Australian sea-level rise ≈10kya or Crater Lake ≈7.7kya), and linguistic reconstruction (Proto-Indo-European myths ≈6-8kya).

- Some fringe theories propose even older origins (e.g., Pleiades myth ≈100kya, San Python myth ≈70kya), but lack strong consensus.

- Oral tradition can be a reliable vehicle for transmitting cultural memory across millennia.

Introduction#

Human myths can endure far longer than written history. Recent research across disciplines – comparative mythology, geology, linguistics, archaeology, and oral tradition studies—building on insights from evolutionary models of consciousness – has uncovered several mythological narratives that may trace back eight millennia or more in antiquity.

This report surveys specific myths around the world that scholars have argued originated at least ~8,000 years ago (circa 6000 BC) or earlier, the evidence supporting these deep chronologies, and the level of scholarly acceptance. A final section highlights notable fringe or non-mainstream theories (those outside consensus but with some argued evidence) regarding ultra-ancient myths. The findings are organized by the methodologies used to date or trace each myth’s origin.

Comparative Mythology and Deep-Shared Motifs#

Comparative mythology examines common motifs in stories from widely separated cultures to infer a shared ancient origin. If the same complex story appears in societies that haven’t interacted in thousands of years, scholars suspect it may descend from an older narrative carried by migrating peoples. Using this approach, some mythic storylines have been traced to the Upper Paleolithic era:

- A Global “Cosmic Hunt” Myth – 15,000+ Years Old: One of the best-supported cases is the Cosmic Hunt motif, in which an animal (often a large bear) is chased into the sky and becomes a constellation (typically the Big Dipper/Ursa Major). Variants of this tale are found across Eurasia and in North America – for example, Greek myth tells of Callisto transformed into the bear Ursa Major, and an Algonquin legend describes hunters and a bear in the stars. Computational phylogenetic analysis by anthropologist Julien d’Huy suggests these scattered versions all descend from a single Paleolithic origin. He reconstructs a proto-myth that existed before humans crossed the Bering land bridge into the Americas, meaning the story could date back ≈15,000–20,000 years. Intriguingly, a famous cave painting from Lascaux in France – the “shaft scene” depicting a man, a wounded bison, and a bird – may be a 17,000-year-old record of this myth (the immobile, wounded bison representing the celestial beast). If so, the Cosmic Hunt would qualify as one of the oldest known mythological narratives. Scholars broadly find the cross-cultural parallels convincing: for instance, specific details (like the bear’s long tail formed by the Dipper’s handle, explained in Siberian and Native American versions as hunters or a bird trailing the bear) strongly indicate a common source rather than coincidence. This deep-time myth is increasingly accepted as a real oral tradition survival, though the exact timeline (15k vs. 20k years) is still being refined.

Figure: The Paleolithic “Shaft Scene” in Lascaux Cave, France (c.17,000 years old), which some scholars interpret as depicting the Cosmic Hunt myth of a great beast hunted – potentially one of the oldest story depictions. The widespread “hunt the bear” constellation myth is thought to date back to at least 15,000 years ago.

- The Seven Sisters (Pleiades) – A Paleolithic Star Myth: Another ancient motif may be the story of the Pleiades star cluster, often envisioned as “Seven Sisters” or daughters pursued by a hunter. Strikingly, cultures on every inhabited continent have traditional stories about these seven stars, commonly explaining why only six are visible (one sister disappears or hides). This suggests a deep common origin. A recent (and controversial) study by astronomer Ray Norris and colleagues proposes that the Pleiades lore could be the “oldest story” in the world, potentially dating back ≈100,000 years to early modern humans in Africa. The researchers note that a faint seventh star (Pleione) would have appeared slightly farther from its partner star in the distant past, perhaps making it visibly distinct ~100k years ago. They hypothesize that prehistoric Africans saw seven stars clearly and crafted a story of seven sisters – a tale carried by migrating humans to Europe, Asia, and Australia. This hypothesis is speculative and not widely accepted yet: critics point out the similarity of Pleiades myths could be due to chance and note that updated star-motion data suggests the cluster’s appearance 100k years ago may not have been dramatically different. Nonetheless, the “Seven Sisters” myth is at least many millennia old. Even conservative analyses concede its core elements predate classical antiquity; for example, the Aboriginal Australian version (the Kungkarangkalpa Dreaming of the Seven Sisters) is woven into rock art and songlines that are believed to be tens of thousands of years old (Aboriginal peoples arrived in Australia ~50,000 years ago, carrying rich star lore). While a 100k-year date is viewed with skepticism, the sheer global spread of the Pleiades story strongly implies a very ancient (Upper Paleolithic) origin – possibly on the order of 10–50,000 years ago, long before recorded history.

- A Common “World Parents” Cosmogony – 20,000+ Years: Beyond specific motifs, entire mythic frameworks may have deep roots. Harvard scholar E.J. Michael Witzel’s comparative study proposes that the majority of Old World and New World cultures share a grand “Laurasian” myth cycle that first coalesced between ~40,000 and 20,000 BC. According to Witzel, myths across Eurasia, the Americas, and Oceania follow a similar overarching narrative: creation of the universe from primordial nothingness or chaos (sometimes an egg or water abyss), the separation of sky-father and earth-mother, the emergence of subsequent generations of gods, a great flood or destruction, and an eventual end of the world. This complex storyline is absent in sub-Saharan Africa and Aboriginal Australia, which have their own older mythologies, suggesting it was an innovation that spread with people out of Africa. Witzel argues the Laurasian mythos likely originated in a single culture of the Upper Paleolithic (perhaps in Southwest Asia) and then spread widely with migrating human groups. If so, its age could exceed 20–30,000 years. He even speculates that some myth themes (like a primordial flood) might trace back to an earlier “Pan-Gaean” tradition over 65,000 years ago, shared by the earliest humans in Africa. These timelines remain hypotheses – Witzel’s theory is bold and not universally accepted (critics say such ancient diffusion is hard to prove). However, it underlines that certain myth patterns (creation from nothing, world parents, flood, etc.) are so ubiquitous that purely independent origin seems unlikely. Comparative evidence thus points to extremely old stratum of myth-making, even if dating it relies on inference. In summary, rigorous motif comparisons have identified a few myths (like the Cosmic Hunt and perhaps the Pleiades and creation/flood cycles) that plausibly date to the Late Paleolithic, well over 8,000 years old.

Myths Linked to Ancient Geological Events (Geo-Mythology)#

Another way to date myths is by linking them to known prehistoric geological or climatic events. If a legend accurately describes something like a sea-level rise, flood, or volcanic eruption that science can date, the myth’s origin can be dated to that event. This emerging field of “geomythology” (pioneered by geologist Dorothy Vitaliano in 1968) has revealed that oral traditions on multiple continents preserve memories of Ice Age transitions and natural disasters from the Holocene dawn:

- Post-Glacial Great Flood Myths – ≈8,000–12,000 Years Old: Myths of a great flood or deluge are nearly universal – from the biblical Noah’s Flood and Mesopotamian Atrahasis/Gilgamesh, to flood stories among Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Pacific Islanders, and others. Some of these could be independent local stories (since floods happen in many places), but scientists have long wondered if they might hark back to real events—as detailed in our comprehensive survey of flood myths at the end of the last Ice Age (~12k–7k BC) when melting glaciers caused global sea levels to rise dramatically. There are a few plausible scenarios: one is the flooding of the Black Sea basin around 5600 BC, when the Mediterranean is thought to have breached the Bosporus – a catastrophic inflow that potentially inspired Near Eastern flood legends. Marine geologists William Ryan and Walter Pitman have argued that this event would have displaced early farming communities around the Black Sea, whose descendants carried the tale into Mesopotamia, eventually influencing the biblical account of a world-consuming flood (though this theory is debated). More generally, coastal inundation at the end of the Pleistocene (when sea levels rose over 100 meters) would have drowned vast land areas worldwide – an estimated ~25 million km² of land lost, roughly 5% of Earth’s land surface. It is conceivable that communities around the world witnessed these ancient drownings of coastal plains and passed down oral memories. Indeed, Witzel notes that a myth of a great flood exists even in some of the oldest myth layers (his “Pan-Gaean” set), potentially making the flood motif tens of thousands of years old. While it’s impossible to pin to one single flood event, scholars increasingly view global flood myths as “folk memories” of real post-glacial sea level rise. In short, the idea of a civilization-destroying flood could date to the End of the Ice Age (c. 10,000–8000 BC), when melting ice and megafloods were part of human experience. This would make the Great Flood myth (in its various cultural forms) on the order of 8–10+ millennia old, even though specific written versions (like the Sumerian or Biblical) are much more recent. (Mainstream consensus is cautious: many flood tales likely arose independently, but geological evidence lends credibility that some are rooted in real prehistoric deluges.)

- Australian Aboriginal Sea-Level Rise Stories – 10,000+ Years Old: The Aboriginal peoples of Australia have provided some of the clearest evidence that oral traditions can survive from the end of the Ice Age. Dozens of Aboriginal coastal myths describe a time when the ocean was lower and then “the sea came in” and flooded the land, creating new coastlines and islands. Remarkably, these stories accurately recall geographic details of the coast as it was over 10,000 years ago. For example, the Ngarrindjeri people of southern Australia tell of their ancestral hero Ngurunderi who chased his wives onto what is now Kangaroo Island; when they angered him, he caused the sea to rise and cut off the island, stranding or turning his wives to stone. Geological studies confirm that Kangaroo Island was connected to the mainland until about 9,500–10,000 years ago, when post-glacial sea level rise submerged the land bridge. Using sea-level curves, linguist Nicholas Reid and geologist Patrick Nunn dated the Ngurunderi myth to roughly 9,800–10,650 years old. They have documented 21 different Aboriginal groups’ stories of coastline inundation, each corresponding to local sea level changes in the period 11,000–7,000 BP (before present). In one case from Western Australia, storytellers could name hills and features now underwater. Such consistency “across 400 generations” led Reid to call it “gobsmacking” evidence of 10,000-year oral continuity. These findings, published in Australian Geographer (2015), have gained scholarly support as credible examples of ultra-long-term oral history. In sum, multiple Aboriginal flood myths explicitly date back to the 8–11th millennium BC based on geological correlation – making them perhaps the oldest continuously told stories on Earth.

Figure: Map of Australia showing 21 coastal locations (numbers) where Aboriginal stories record a time of lower sea level, as analyzed by Nunn & Reid. These myths describe land now under the sea, meaning they originated before 7,000 years ago when seas rose to present levels. Some date to ~10,000 years BP, marking them among the longest-lived oral traditions.

- Ancient Volcanic Eruptions in Myth – ~7,000–8,000 Years: Myths can also encode dramatic events like volcanic eruptions. One famous example comes from the Native American Klamath tribe of Oregon (northwestern USA). The Klamath have a sacred story about a titanic battle between the sky god Skell and the underworld god Llao—an example of how creation myths can preserve historical events, which caused Llao’s fiery mountain to collapse and form a deep crater filled with water – Crater Lake. This aligns precisely with the cataclysmic eruption of Mount Mazama ~7,700 years ago, which indeed collapsed to create Crater Lake. Geological dating of Mazama’s eruption (c.5700 BC) indicates the Klamath narrative has been preserved for approximately 7.7 millennia. Patrick Nunn notes this as a North American parallel to the Australian long-term memories. Similarly, in Australia, an Aboriginal story from the Gunditjmara people describes how the ancestral creator Budj Bim revealed himself in fire and lava – strikingly consistent with the eruption of a local volcano (Budj Bim, formerly Mt. Eccles) around 37,000 years ago, though that date stretches credulity for oral transmission (some suggest the story was renewed by a smaller eruption ~7,000 years ago). Another case: Pacific Islander myths have preserved volcanic events – e.g. on Fiji, a legend about the god chasing away a mountain that “belched fire” was long thought fanciful until archaeologists found it corresponded to an eruption ~3,000 years ago. Compared to floods, definitive volcano myths older than 8k years are rarer (many known examples, like the destruction of Thera (Santorini) in ~1600 BC inspiring the Atlantis motif, are more recent). Nonetheless, the Klamath Crater Lake myth is widely cited as evidence that oral tradition can survive ~7–8 millennia in a stable culture. It stands just at our 8,000-year cutoff (and likely originated shortly after the eruption ~7700 years ago). The strong consensus is that this myth does commemorate that specific eruption – a breathtaking time capsule of a Holocene geological disaster witnessed by humans. Geomythology thus provides firm anchors for myth antiquity: whenever a myth corresponds to a datable ancient event (be it rising seas or erupting peaks), it implies the story first emerged at that time, often 8–10,000+ years ago, and was faithfully transmitted to the present.

Reconstructed Proto-Language Myths (Linguistic & Archaeological Evidence)#

Linguists and historians have attempted to reconstruct myths of long-lost cultures by comparing legends and deities in descendant cultures. If related languages and peoples share similar gods or mythic themes, those may derive from their common ancestral culture, allowing us to push a myth’s origin back to the time of that proto-culture. Two prominent cases involve the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) and Proto-Afroasiatic peoples:

- Proto-Indo-European Myths – ≈6,000–8,000 Years Old: The Indo-European language family (which includes Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, Norse, etc.) arose from an ancestral people living around the Late Neolithic. Scholars estimate PIE was spoken roughly 4000–2500 BC (i.e. 4.5–6.5k years ago) under the mainstream “Steppe/Kurgan” hypothesis, or as early as ~6500–5500 BC (≈8–9k years ago) under the alternative “Anatolian” hypothesis. By comparing mythologies of Indo-European cultures, researchers have reconstructed several PIE-era myths that would date back to at least that timeframe. One well-supported example is the myth of the “Divine Twins.” All major Indo-European traditions have stories of twin brothers or horsemen with identical or complementary roles (examples: the Ashvins in the Vedas, the Dioscuri Castor and Pollux in Greece, and similar twins in Lithuanian, Celtic, and Norse lore). These share such specific correspondences (often portrayed as sons of the Sky God or Sun, associated with horses or chariots, rescuers of mortals) that scholars are confident the Divine Twins myth goes back to Proto-Indo-European antiquity. Linguist-historians Gamkrelidze and Ivanov (1995) noted not only the motif’s recurrence but even cognate names in different IE branches, indicating an origin in the common PIE culture. Therefore, the Twins myth likely originated at least ~6,000–7,000 years ago, during the PIE period. (If one adopts the older timeline for PIE, it could be ~8–9,000 years old.) Other reconstructed PIE myths include the Sky Father (Dyēus Ph₂tḗr, ancestral to Zeus/Jupiter/Dyaus) and a Storm God vs. Dragon combat myth (e.g. Vedic Indra vs. Vṛtra, Thor vs. Jörmungandr, etc.), as well as a creation story involving a sacrifice of a primordial being (the Manu and Yemo myth). For instance, PIE texts likely had a tale of twin progenitors where one (Manu = “Man”) sacrifices the other (Yemo = “Twin”) to form the world – a theme inferred from later Indic, Iranian, and Norse accounts. These hypothetical PIE narratives would date to the time when the Proto-Indo-Europeans were a unified culture, i.e. around the 5th–4th millennium BC (if not earlier). While we lack written records from PIE times, the consistency of myth elements across Indo-European societies lends credence to these deep reconstructions. Most scholars accept that the Indo-Europeans shared certain deities and mythic concepts, making those myths at least as old as the breakup of the PIE community (so minimum 6–7,000 years before present). This is just below our 8k threshold in the stricter timeline, but considering the possibility of a Neolithic PIE (or “Indo-Hittite” ancestor around 7000–6000 BC), it’s reasonable to include PIE mythic themes as ~8,000 years old. The consensus is moderate: PIE myth reconstruction is a robust field (supported by linguistic evidence), although some details remain debated. In short, Proto-Indo-European myths provide a window onto Bronze Age and late Stone Age beliefs, making them among the oldest inferable narrative traditions in the Old World.

- Proto-Afroasiatic and Other Early Myths – 8,000+ Years?: Compared to PIE, reconstructing myths for other proto-families (like Afroasiatic or indigenous groups) is more challenging, as these lineages are extremely old and diverse. Afroasiatic (ancestor of ancient Egyptian, Semitic, Berber, etc.) likely dates to ~10–12,000 years ago or more, but there is no agreed corpus of “Proto-Afroasiatic mythology” – the cultures diverged too vastly. A few scholars have speculated on common Afroasiatic themes (for example, a possible early Creator god and chaos-serpent myth, given parallels in Egyptian (Ra vs. Apep) and Mesopotamian myth), but evidence is thin. Instead, insights have come from archaeology: for instance, ancient rock art and artifacts hint at belief systems in the late Paleolithic. A famous set of prehistoric European figurines – the “Venus” fertility sculptures (~30,000 BP) – suggest a widespread reverence for a Mother Goddess or fertility spirit, which some see as a precursor to later mother-goddess myths in Neolithic and historic times. If that continuity is real (a big if), one could argue an Earth-Mother myth dates back tens of thousands of years in Eurasia. Similarly, the ritual burial of cave bears by Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens has been interpreted as a proto-Bear Cult; intriguingly, many northern cultures (Siberian, Finnic, Native American) historically have myths of the bear as an ancestor or spirit, possibly reflecting an extremely ancient tradition. However, these connections are speculative – we lack a clear, unbroken line as we have for PIE traditions. Overall, linguistic and archaeological reconstruction can push some myth elements to 8,000+ years, but with less certainty. The Proto-Indo-European case remains the clearest, with several securely reconstructed myths ~6–8 millennia old, whereas attempts to reconstruct mythologies of earlier proto-cultures (Afroasiatic, or even “Proto-Human” in Witzel’s terms) are considered intriguing but not yet verifiable.

Other Evidence of Ancient Myth Continuity#

Beyond texts and geology, researchers have looked at material culture and oral performance for clues of myth longevity. Ritual practices, symbols in rock art, and even long-term cultural taboos can sometimes be linked with mythic narratives, suggesting those narratives’ antiquity:

- Ancient Rock Art and San “Python” Myth – 70,000 Years Ago?: In 2006, archaeologists discovered what may be the world’s oldest known ritual site in the Tsodilo Hills of Botswana – a cave featuring a huge rock carved in the shape of a giant python, with stone tools and pigments dated to an astonishing 70,000 years ago. The python is a central figure in the mythology of the local San (Bushmen) people even today: according to San creation myth, humanity descended from a great python, and the dry gully winding around the hills was made by the python’s movements in search of water. The lead archaeologist, Sheila Coulson, found that the cave was likely a ritual shrine where Stone Age people performed ceremonies in front of the python rock (hundreds of man-made indentations enhanced the snake-like appearance, and artifacts like spearheads were placed in what seems like offerings). This suggests a continuity of religious symbolism: the San worship of the python could date back to the Middle Stone Age, making their myth of the Python Creator potentially tens of thousands of years old. Of course, it is impossible to prove an unbroken oral tradition across 70 millennia – that stretch is mind-boggling, and the culture of 70k years ago would not be identical to the San of today. However, the Tsodilo Hills discovery at least shows that key elements of San cosmology (the ritual importance of the python) were present in the distant past. It implies that the San mythos as a whole (often cited as one of humanity’s oldest mythological systems) may preserve themes from the very origin of Homo sapiens’ spiritual life. Even if the specific story has evolved, the fact that the San still revere the python in myth and the site is still sacred to them hints at a cultural memory of extreme depth. Many archaeologists cautiously regard this as a unique but credible case of a mythic tradition (or at least a religious icon) enduring on the order of tens of millennia. In general, indigenous peoples like the San and Australian Aboriginal groups, with continuous habitation and oral transmission in one region, offer the best windows into myths of the Paleolithic.

- Myth and Ritual Continuity: Myths tied to enduring ritual practices can also survive for immense timescales. For example, in southern Africa, the San’s trance dance and the figure of the trickster/healer are depicted in rock paintings thousands of years old, linking to present-day San myths of the trickster god / Kaggen. In Europe, some have speculated that the widespread Upper Paleolithic practice of shamanic cave art hints at mythic concepts (like animal-human spirit beings) that later reappear in myths of shamans or therianthropes. One could argue that the concept of a shamanic animal-spirit guide – seen in 15,000-year-old cave paintings and still alive in Eurasian indigenous myths – is a mythic motif of Paleolithic origin. Another possible Paleolithic continuity is the Horned God or master-of-animals figure (e.g. a half-stag, half-human drawing in a 12,000-year-old French cave might be an early representation of a lord of beasts similar to later Celtic Cernunnos). While these parallels are intriguing, they remain hypothesized and aren’t “dated” in a rigorous way. They do, however, reinforce that some mythic themes (animal deities, mother goddesses, trickster figures) could be as old as humanity’s artistic record, which is 30–40,000 years or more. Such claims rely on interpreting prehistoric art and artifacts in light of current myths, which is subjective. Still, when combined with genetic and anthropological evidence of cultural continuity, they make a case that certain myth elements might reach back to the Ice Age.

Conclusion#

Multiple lines of evidence indicate that myths are far more ancient than previously assumed. Traditionally, scholars without evidence assumed oral tales couldn’t survive more than a few thousand years. Now, through comparative motif analysis, geological dating, and linguistic reconstruction, we have identified myths with likely origins 8,000, 10,000, even 15,000+ years ago – truly “Ice Age” stories that are still told in some form today. Below is a table summarizing key examples, including the myth, estimated age, region of origin, method of dating, and scholarly consensus level:

Summary Table of Mythic Traditions Over 8,000 Years Old#

| Myth or Mythic Theme | Proposed Origin (Age) | Region/Cultural Source | Dating Method | Scholarly Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmic Hunt (Great Bear) – Animal pursued into sky becomes stars (Ursa Major) | ~15,000–20,000 years old (Upper Paleolithic) | Widespread: Eurasia & N. America (e.g. Siberian, Greek, Algonquin) | Comparative mythology (shared complex motif) and inferred spread before Bering migration | High-Moderate: Strong evidence of common origin; widely accepted as a very ancient myth. |

| “Seven Sisters” (Pleiades) – Seven star-maidens, with one missing | Possibly ~100,000 years old (speculative); at least several tens of millennia old | Global: noted in Greek, Indigenous Australian, African, Americas, etc. | Comparative motif + astronomical modeling of star positions | Contested: Similar myths worldwide; some argue common Paleolithic origin, but many scholars see coincidence. |

| Great Flood/Deluge – Global flood destroying an earlier world | ~8,000–12,000 years old (post-glacial sea rise era) | Worldwide motif (Mesopotamia, India, Americas, Pacific, etc.) | Geomythology: correlation with end-Ice Age floods (e.g. sea level rise, Black Sea ~7.6k BP) | Moderate: General agreement that some flood myths echo real prehistoric flooding, but likely mixed. |

| Australian Aboriginal Inundation Myths – Stories of land lost to the sea | ~9,000–11,000 years old (early Holocene) | Australian Aboriginal groups (e.g. Ngarrindjeri, Tiwi, etc. at 21 coastal sites) | Geomythology + Oral history: matched with scientific sea-level data after last Ice Age | High: Well-documented and published; strong consensus that these specific oral traditions date back. |

| Crater Lake (Mount Mazama) Myth – Volcano god’s collapse | ~7,700 years old (c.5700 BC) | Klamath people, Pacific Northwest North America | Geomythology: corresponds to Mount Mazama volcanic eruption dated ~7.7k BP | High: Widely cited as a confirmed ancient oral record; proof of ~8k-year oral memory. |

| Proto-Indo-European “Divine Twins” – Twin horsemen demi-gods, sons of sky | ~6,000–8,000 years old (PIE homeland era) | Proto-Indo-European culture (steppe/Anatolia); attested later in Vedic, Greco-Roman, etc. | Linguistic reconstruction: shared myth motifs & names in all Indo-European branches | High (within IE studies): Broad agreement on PIE twin myth and other deities; age tied to PIE timeline. |

| San/Bushmen “Python Creation” – Humans created by a great Python, sacred serpent rituals | Possibly ~70,000 years old (Middle Stone Age Africa) | San peoples of Southern Africa (Botswana) | Archaeological evidence: Tsodilo Hills python rock shrine dated 70k BP, linked to ongoing San myth | Moderate-Fringe: Compelling ritual evidence but extremely long continuity; suggests great antiquity. |

Table: Examples of Myths with Proposed Origins ≥8,000 Years Ago. Each entry lists the myth, estimated age of origin, cultural context, how it’s dated/traced, and the level of scholarly consensus. Generally, myths supported by multiple lines of evidence enjoy higher consensus.

Fringe and Non-Mainstream Deep-Time Myth Theories#

In addition to the above cases, which are drawn from academic research, there are a number of fringe or non-mainstream theories proposing even greater antiquity for certain myths. These theories are not fully accepted by scholars but offer interesting interpretations, often attempting to link mythology to prehistoric events or lost civilizations. Below we outline a few such ideas (presented as hypotheses, not established fact):

- “Seven Sisters” 100k Hypothesis: As mentioned, the claim that the Pleiades “seven sisters” story could be ~100,000 years old is considered speculative. Norris et al. (2020/21) argued that humans still in Africa told this star story before dispersing globally. While intriguing, this pushes oral tradition to an extreme timescale. Most experts find the evidence circumstantial (the gendering of Orion and Pleiades could easily arise independently). In short, a 100k-year continuous myth is beyond mainstream acceptance, though it makes for a thought-provoking hypothesis about the longevity of stargazing lore.

- Atlantis and Ice Age Floods: The legend of Atlantis, first recorded by Plato (~360 BC), speaks of a great island civilization that sank beneath the sea “9,000 years” before his time. A fringe view holds that Atlantis was not mere fiction but a blurred memory of real events around 9600 BC – essentially a mythical recording of the global sea rise and flooding at the end of the Ice Age. Some have associated Atlantis with the flooding of coastal plains or continental shelves (e.g. the inundation of Sundaland in Southeast Asia, or the Mediterranean Basin refilling, etc.). However, mainstream historians note that Plato’s account was likely an allegory; he seemingly invented Atlantis as an idealized society to make a philosophical point. Elements of the story (hubris of a great society, divine punishment by flood) are thematically universal. That said, certain details could have been inspired by more recent events known to the Greeks or Egyptians – for example, the eruption of Santorini (~1600 BC), which destroyed the Minoan island civilization and created tsunami devastation, is often cited as a possible template for Atlantis. Geologist Patrick Nunn notes that Plato wrote in a region prone to volcanic island disasters, so he likely drew on those real cataclysms to lend realism to Atlantis. In conclusion, while Ice Age Atlantis theories capture public imagination, academic consensus sees Atlantis as a myth inspired by Bronze Age events and imaginative storytelling rather than a literal 11,600-year-old oral memory. It remains a fringe notion that Atlantis preserves a Stone Age memory. For a detailed exploration of the etymological connection between Atlantis and the Atlantic Ocean, see our article on Atlantic Atlantis Shared Root.

- Lost Continent of Kumari Kandam: In Tamil tradition (South India), there are medieval literary references to Kumari Kandam, a vast land to the south of India that was lost to the ocean. Tamil nationalist interpretations in the 19th–20th centuries equated this with Lemuria, a hypothetical submerged continent, claiming Tamil culture spanned back >10,000 years on this lost land. Some modern writers suggest these tales could be distant memories of real sea-level rise that submerged parts of the Tamil coastal plain after the last Ice Age. Indeed, Tamil lore laments the “submerged land of Kumari” with a sense of cultural loss. However, historians find that the Kumari Kandam story emerged in Tamil literature only around a thousand years ago, likely as a symbolic narrative of a golden age rather than an actual preserved memory of 10k-year-old events. Patrick Nunn observes that such stories of sunken lands with moral or nostalgic overtones appear in many cultures (e.g. in Brittany, Wales, etc., legends of drowned kingdoms like Ys or Cantre’r Gwaelod). They often serve as “echoes of ancient coastal change” but filtered through much later imagination. The idea that Kumari Kandam’s myth reliably encodes a Pleistocene inundation (~11–12k BP) is generally not supported by evidence – it’s considered a pseudo-historical interpretation. Thus, Kumari Kandam remains a non-mainstream theory for deep antiquity, though it highlights how post-glacial sea loss is a theme that fascinated later storytellers too.

- Myths of Extreme Antiquity (Beyond Verbal Tradition): A few researchers have gone as far as to propose that certain symbols or archetypes in myth might be “hardwired” from the Paleolithic even if oral continuity is broken. For instance, psychologist Carl Jung’s idea of archetypes posited that similar myths (the Great Mother, the Hero’s Journey) recur not from direct transmission but from the collective unconscious – thus they could be said to date back to the dawn of Homo sapiens in a psychological sense. These ideas veer away from testable history into theory, so they’re noted as fringe. Another fringe concept is that Upper Paleolithic cave art is a literal recording of myths that we can decode – for example, one researcher claimed Lascaux’s star-like dots and animal figures map out constellations and tell a story corresponding to the zodiac. If true, that would push known star myths to ~17,000 BP or more. However, most archaeologists are skeptical of these specific readings; it’s hard to distinguish mythic intent from naturalistic art in caves.

In sum, fringe theories sometimes attribute extreme ages (≫10,000 years) to myths by linking them to speculative lost continents, astronomical cycles, or psychological universals. While these often lack robust evidence and are not accepted by mainstream scholarship, they underscore a key point: many myths feel ancient, and it’s possible that kernels of them do reach extraordinary antiquity, even if the current forms are embellished. Researchers remain appropriately cautious – extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof, which is seldom available. The academically supported cases (like those in the main sections above) stop around ~10–15k years, with a few tantalizing hints going further (San python ritual, etc.).

Nonetheless, the field of archaic myth studies is rapidly evolving. Interdisciplinary methods continue to uncover surprises – such as the Australian stories proven to be 10k years old, once thought unimaginable to preserve. As techniques improve, we may validate more of what indigenous elders have always insisted: that they carry knowledge from time immemorial. Myths are not static fossils, but living memories that can endure vast spans of time, faithfully passed down “accurately across 400 generations”. The examples surveyed above compel us to recognize oral tradition as a powerful vehicle for history, capable of transmitting events and ideas from the Neolithic and even late Pleistocene to the present day.

FAQ #

Q 1. How can myths possibly survive for over 8,000 years? A. Through accurate oral transmission, often aided by stable cultures, ritual practices, mnemonic devices (like songlines), and linking stories to enduring landscape features or celestial patterns.

Q 2. What is the strongest evidence for such ancient myths? A. Geomythology provides compelling evidence, particularly Australian Aboriginal stories accurately describing coastlines from 10,000+ years ago, confirmed by geological sea-level data. The Klamath myth precisely matching the ~7,700-year-old eruption forming Crater Lake is another strong case.

Q 3. Are claims of 100,000-year-old myths widely accepted? A. No, claims for myths dating back >20,000 years (e.g., the 100kya Pleiades theory or 70kya San Python myth) are generally considered speculative or fringe due to the immense timescale and lack of definitive proof for unbroken transmission.

Sources#

- d’Huy, Julien (2013). “A Cosmic Hunt in the Berber Sky: A Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Palaeolithic Mythology.” Anthropos (pre-print on ResearchGate). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259193627_A_Cosmic_Hunt_in_the_Berber_sky_A_phylogenetic_reconstruction_of_Palaeolithic_mythology

- Norris, Ray P.; Norris, Barnaby R. M. (2020). “Why Are There Seven Sisters?” arXiv pre-print (astro-ph/2101.09170). https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.09170

- Witzel, E. J. Michael (2012). The Origins of the World’s Mythologies. Oxford University Press. https://avalonlibrary.net/ebooks/E.%20J.%20Michael%20Witzel%20-%20The%20Origins%20of%20the%20World’s%20Mythologies.pdf

- Nunn, Patrick D.; Reid, Nicholas P. (2015). “Aboriginal Memories of Inundation of the Australian Coast Dating from 7,000 Years Ago.” Australian Geographer 46 (1): 15–32. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00049182.2015.1077539

- National Park Service (Klamath Tribes) (2001). “Legends Surrounding Crater Lake.” In Historic Resource Study, Crater Lake NP. US National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/crla/hrs/hrs4a.htm

- Ryan, William; Pitman, Walter (1999). Noah’s Flood: The New Scientific Discoveries About the Event That Changed History. Simon & Schuster. https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Noahs-Flood/Walter-Pitman/9780684859200

- Vitaliano, Dorothy B. (1973). Legends of the Earth: Their Geologic Origins. Indiana University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Legends-Earth-Their-Geologic-Origins/dp/0253147506

- Gamkrelidze, Thomas V.; Ivanov, Vjaceslav V. (1995). Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Grammar. Mouton de Gruyter. https://archive.org/details/indo-european-and-the-indo-europeans-a-reconstruction-and-thomas-v-gamkrelidze-vjaceslav-v-ivanov

- Coulson, Sheila (Univ. of Oslo press release) (2006). “World’s Oldest Ritual Discovered — Worshipped the Python 70,000 Years Ago.” ScienceDaily news release. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/11/061130081347.htm

- Nunn, Patrick D. (2018). The Edge of Memory: Ancient Stories, Oral Tradition and the Post-Glacial World. Bloomsbury Sigma. https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/edge-of-memory-9781472943279/