TL;DR

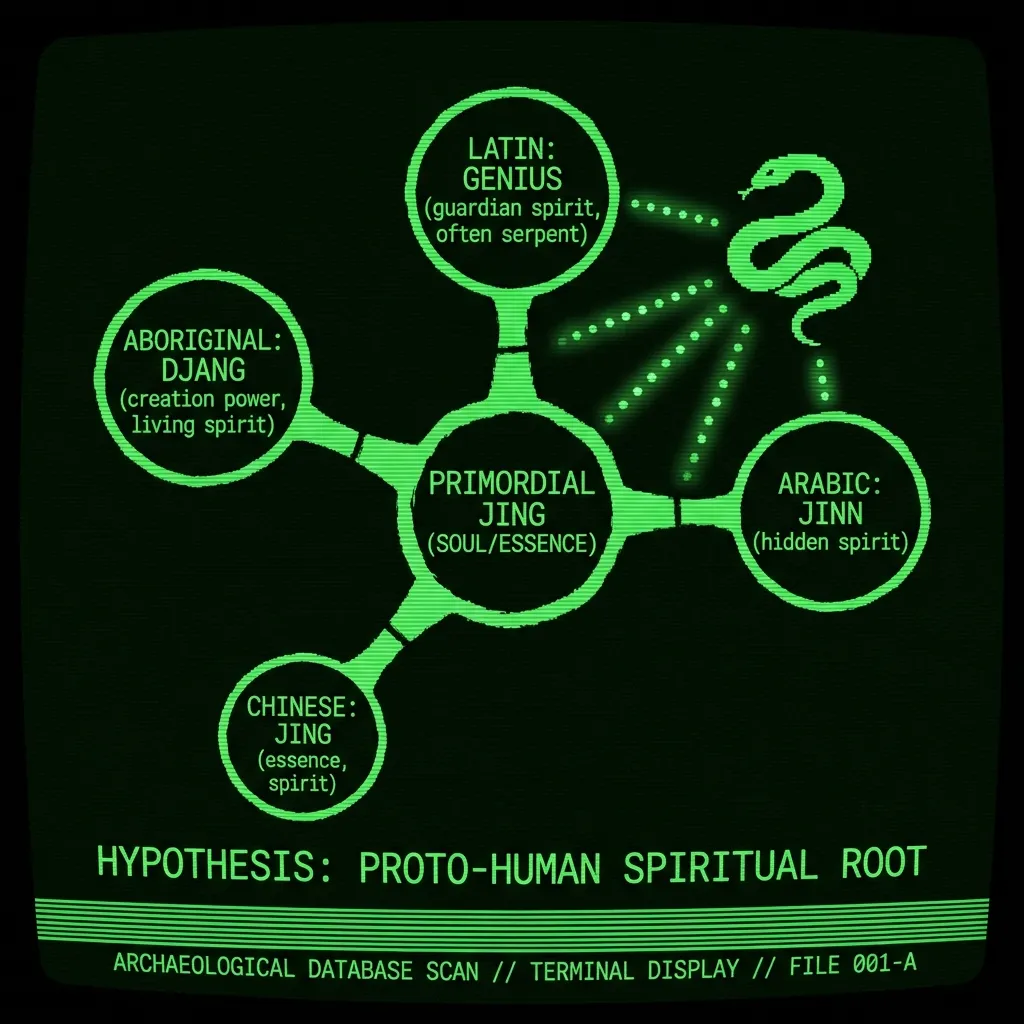

- The “Jing hypothesis” proposes a primordial word sounding like “jing,” “gen,” or “djin” once meant soul/spirit in early human culture.

- Evidence includes Latin genius (guardian spirit), Arabic jinn, Chinese jing (essence), and Aboriginal Australian djang (creation power).

- The hypothesis links this root to ancient serpent cults where breath/spirit was synonymized with the animating force of life.

- Across languages, terms for soul, creation, kinship, and spiritual beings often contain similar phonetic patterns (gen/jin/jing sounds).

- While speculative, the theory suggests a lost ur-language of spirituality predating known language families.

FAQ#

Q1. What evidence supports the Jing hypothesis?

A. Similar-sounding words across unrelated languages: Latin genius, Arabic jinn, Chinese jing, Sanskrit jana, Aboriginal djang—all relating to spirit, essence, or creation with shared phonetic patterns.

Q2. How does this relate to serpent symbolism?

A. Ancient serpent cults worldwide linked snakes to breath/spirit/soul concepts, possibly preserving the original jing root in names for serpent deities and spiritual concepts.

Q3. Is this theory accepted by mainstream linguistics?

A. No, it’s highly speculative. Mainstream linguistics explains similarities through known language families or cultural borrowing rather than a single primordial root.

Q4. What makes this hypothesis intriguing despite being speculative?

A. The remarkable frequency of gen/jin/jing sounds in spiritual contexts across isolated cultures suggests either ancient common origins or profound convergent symbolism in human consciousness.

The “Jing” Hypothesis: An Ancient Root of Soul and Spirit

Overview of the Theory#

The “Jing hypothesis” posits that a primordial word – sounding like “jing”, “gen”, or “djin” – once meant soul, spirit, or a fundamental life-force in early human culture. Proponents speculate that this concept dates back before the Indo-European languages, perhaps to a time of widespread serpent cults and prehistoric shamanic religion. According to this theory, echoes of the root can be found in diverse languages and mythologies around the world, hidden in words for spirit, mind, breath, or even in the names of mythic beings. Over millennia, as cultures diverged, the original jing/gen root may have branched into many forms – from ancient deities and demons to terms for personhood and creation. The hypothesis is admittedly speculative, but it weaves a fascinating narrative connecting linguistic fragments and spiritual motifs across continents.

At its heart, the Jing hypothesis suggests an ancient unity of concept: the idea that breath or creative essence was synonymous with spirit, and that this essence was symbolized by the serpent. Early humans, perhaps members of a worldwide “snake cult,” might have used a similar sound to denote the animating spirit or guiding soul. This primordial term could have accompanied the spread of early religious practices. Now, long after the original meaning was obscured, we find linguistic footprints of that word in far-flung places – from the Latin genius to the Arabic jinn, from Chinese jing to Aboriginal Australian djang. Below, we’ll explore a range of examples that illustrate this pattern, painting a picture of a possible ancient root that transcends any one culture.

Ancient Origins: Serpent Cults and the Breath of Life#

Many scholars have noted that serpent worship appears in some of the oldest religious traditions. An 1873 paper observed that “the serpent has been viewed with awe or veneration from primeval times, and almost universally as a re-embodiment of a deceased human being,” associated with wisdom, life, and healing. In other words, early peoples often saw snakes as incarnations of the spirit – perhaps the spirits of ancestors or deities. Some legends even claim humans descended from a serpent ancestor. It’s in this context that the Jing hypothesis situates the elusive root word for “soul.” If a prehistoric serpent-centered religion shared a concept of the soul, the sound attached to that concept might have spread far and wide.

A common theme in ancient spirituality is the identity of breath with spirit. For example, in many languages the word for breath also means soul or life-force (Latin spiritus = breath, Greek pneuma = breath/spirit, Sanskrit prāṇa = life-breath, etc.). The Jing hypothesis aligns with this, suggesting the original “jing” meant something like “breath-soul.” An intriguing case comes from the Noongar people of Australia: their Rainbow Serpent creator is called the Waugal or Wagyl, and in Noongar language “Waugal or waug means soul, spirit or breath.”. In their lore, the great serpent Waugal carved out rivers and waterholes, and those waterholes hold a life essence called djanga (often translated as “living spirit” or “consciousness” in people). Here we see the fusion of serpent imagery with the idea of breath = life, exactly the kind of ancient linkage the hypothesis emphasizes.

It’s theorized that as early humans migrated and formed new cultures, they carried this serpent-spirit cult vocabulary with them. Over time the original pronunciation could shift (“jing” to “gen” to “jin,” etc.), and the meaning could morph (from literal spirit to genius or ancestor, for instance). Yet the core idea – a hidden guiding spirit, a creative essence associated with life and death – would remain. The next section presents a series of examples in which terms reminiscent of jing/gen appear in spiritual or existential contexts. Individually, any single example could be coincidence – but together, they strengthen the case for an ancient connection.

Echoes of “Jing/Gen” in World Languages and Myths#

Many cultures contain words or names that sound like “jing/gen” and relate to souls, spirits, creation, or even to mythical serpents and spirit-guides. Below is an organized survey of such examples, ranging from well-established linguistic roots to legendary beings. These examples illustrate how a single primordial concept might have left traces across different civilizations:

Latin Genius – In ancient Rome, the genius was a personal guardian spirit assigned to each person (and place) at birth. The word comes from Latin genius “household guardian spirit,” which in turn stems from Proto-Indo-European *gen- meaning “to beget, produce.” Originally, genius meant the generative force or tutelary spirit of one’s clan or family. Over time it also came to mean a person’s character or talent (and eventually, exceptional intellect in modern English). Importantly, Roman genius was often depicted as a serpent or accompanied by serpents in art and altar symbols. Here we see a direct link between the gen- root, a spirit guardian, and the serpent motif – very much in line with the Jing hypothesis.

Greek Genesis – The term Genesis (as in the Book of Genesis) means origin or creation, also derived from the same Indo-European root *gen- (“beget, create”). It’s intriguing that the creation story in Western tradition carries the gen root, while a concept of soul (the Roman genius) also carries that root. The hypothesis suggests this is not coincidence: both creation-of-life and the soul-of-life were expressed with gen in distant antiquity. In effect, genesis (creation) and genius (creative spirit) may share more than just phonetics – possibly a common conceptual origin in a time when creating life and guiding life were seen as the same divine power.

Navajo Diyin and Etruscan Lares – The Navajo people refer to their holy ancestral spirits as Diyin Dineʼé, usually translated “Holy People.” The word diyin (pronounced like “djin”) denotes something sacred or spiritual. Half a world away, in ancient Italy, the Lares were guardian ancestral spirits in Roman religion, sometimes considered predecessors to the concept of the genius. Notably, the name Lar in Etruscan means “lord”, and the Lares were associated with snakes in household shrines. One of the chief Roman goddesses of ghosts was Mania, the mother of the Lares; tellingly, “mania” is the linguistic root for words like mania (madness) and relates to mens (mind). This underscores how ancient words for spirit/mind often transform into words for mental conditions – evidence that concepts of mind, spirit, and ancestor were tightly interwoven. In both Navajo and Roman examples, we find a din/jin sound (diyin, genius, possibly an echo in Lar-th as well) linked to guiding spirits of the dead or the living.

Arabic Jinn – Arabic jinn (from which English genie is derived) are unseen spirits in Middle Eastern lore. The Arabic root jinn means “to hide/conceal,” but some scholars have speculated on a connection with the Latin genius. In fact, “some scholars relate the Arabic term jinn to the Latin genius – a guardian spirit of people and places in Roman religion – as a result of syncretism during the Roman Empire”. In other words, when the Romans ruled the Near East, people may have equated their local spirits with the Roman genius, merging the concepts. This view is not universally accepted (the mainstream origin of jinn is from Semitic jnn, “hidden”), but it’s tantalizing that jinn and genius were once directly linked in the historical record. Furthermore, another theory holds that jinn came from an Aramaic word ginnaya meaning tutelary spirit – essentially the same idea as a guardian genius. And intriguingly, in ancient Persia (pre-Zoroastrian Iran), a class of female underworld spirits was called Jaini, which sounds like “jani” or “jinn.” In Zoroastrian tradition, there is also Daēnā (later Den or Din), meaning one’s inner self or conscience, often personified as a guiding spirit that leads the soul after death. The Arabic word dīn (دين) means faith or religion, and while it’s not linguistically derived from daēnā, the phonetic resemblance (din/dzen) adds to the tapestry of djin-like terms related to the soul and guidance. All these parallels suggest that a djin/gen concept was present across the Near East, in both language and myth – whether by common origin or convergent symbolism.

Indian Jana, Jain, and Snake Deities – In Sanskrit, the root jan- means “to generate or be born,” visible in words like janma (birth) and janata (people). The Indo-European gen- and Sanskrit jan- are equivalent (the G~J sound shift). Thus the word jīva (life, soul) and jan (person) share an ultimate root with genus and generate. The hypothesis sees this as part of the pattern – the people are “the born ones” and their essence is life. In Indian religion, we also encounter the Jina (a spiritual victor or enlightened being in Jainism) – not etymologically from gen- but interestingly similar in sound. Jain tradition and others in India are full of serpent symbolism: for example, many Jain and Hindu gods are sheltered by Nāga serpents. In Buddhism and Hinduism, nagas are snake-beings often depicted as door guardians at temple entrances. This detail is remarkable: in Roman religion the genius loci (spirit of a place) was often represented by a serpent at the threshold of a home or town, and in Asia we see serpents guarding sacred doorways – possibly an independent development, but perhaps reflecting an ancient idea that serpents are protectors of spiritual gateways. The word naga itself doesn’t contain gen, but the role is analogous to a genius. Meanwhile, the supreme Vedic god of death and afterlife, Yama, has two watchdogs in myth, highlighting again the dog as psychopomp motif. And one of Yama’s epithets is Vaivasvata, sometimes linked to a figure named Manu (the primordial man – note manu relates to mind and man). We mention this because Manu and Mania (from Rome) both derive from the Indo-European men- (mind) root, reinforcing that across cultures the soul/mind concept often has a shared linguistic heritage alongside the gen root. In summary, India’s languages and myths contribute pieces to the puzzle: jan/gen for birth and people, and serpents or dogs guarding the spirit – all resonating with the Jing hypothesis.

Chinese Jing (Essence) – In Chinese philosophy and medicine, the term jīng (精) refers to essence – the essential life force or vital fluid of the body. It can mean not only physical essence (like reproductive essence) but also a spiritual essence or refined energy. Notably, jing in Chinese can carry the connotation of spirit or soul in certain contexts (for example, 精气神 jīng-qì-shén are the “Essence, Energy, Spirit” – the Three Treasures of life). This is likely a coincidental similarity in sound (Chinese jing has a different etymology), but it is fascinating that the word sounds like “jing” and denotes the life force. Additionally, the famous I Ching (Yìjīng, “Book of Changes”) bears the name Jing (Classic) – again not related in meaning, but an ancient text concerned with cosmology and fate carrying the name jing could be seen as poetic alignment. The Chinese word xīn (心) meaning heart-mind also evolved over time from denoting the physical heart to the seat of consciousness. While xīn is not phonetically similar to gen, it reflects a parallel evolution: early cultures everywhere grappled with naming the invisible part of us that thinks and feels – heart, mind, spirit, breath, or something else. The Jing hypothesis would say that “something else” in many cases was a word like jing. Even the name of China’s perhaps oldest secretive religious tradition, Xiantiandao (Way of Former Heaven), involves worship of a mother goddess and dragons – possibly a distant echo of serpent-centric spirituality.

Heavenly Dogs – Tengu and Tiangou – As cultures shifted from serpents to other psychopomps, dogs often took on the role of guiding or guarding souls. In East Asia, we see a striking example: the Japanese Tengu (天狗) and the Chinese Tiāngǒu (天狗). The word tiangou literally means “Heavenly Dog”, a mythic creature in China said to devour the sun or moon during eclipses. Japan borrowed the term tengu from China, but in Japanese folklore Tengu became birdlike goblins rather than actual dogs – yet they kept the name “Heavenly Dog.” The key point is the concept of a supernatural dog linking heaven and earth. Now, the Jing hypothesis speculates that even the names of certain dog breeds or legendary canines might hark back to the ancient djin idea. For example, the wild Dingo of Australia (which arrived millennia ago with seafarers) was revered by some Aboriginal groups – one legend says the Dingo brought the secret of fire to humans. The name “dingo” comes from an Aboriginal language (Dharug diŋgo) referring to a domesticated dog, so on the surface it’s unrelated. But it’s evocative that din-go contains din, and we find diyin means “spirit” in another Aboriginal language. Similarly, the Korean breed Jindo (진돗개), famous for loyalty and often semi-wild on Jindo Island, shares the jin sound. While Jindo is just a place name, Korean folklore is rich with dog guardians (for example, the mythical haetae lion-dog). The hypothesis playfully suggests that perhaps ancient people named some revered dogs with the jin/gen sound because they saw them as spirits or guides. Whether or not the dingo or Jindo names truly connect, it’s true that around the world – from Anubis in Egypt to Cerberus in Greece – dogs are ubiquitous in spiritual roles. The “Heavenly Dog” Tengu is an explicit linguistic example of that, preserving the idea in its name. This could indicate an age-old interchangeability between snake and dog as the animal form of a guiding spirit: when you combine a snake’s immortality symbolism with a dog’s loyalty and guiding ability, you get the image of a psychopomp – an escort of souls.

Australian Aboriginal Djang, Wandjina, and Quinkan – Australian Aboriginal cultures, among the oldest continuous traditions on Earth, have striking terms that resonate with the jing sound. We already saw Waugal/Wagyl, the Noongar rainbow serpent, whose very name means spirit/breath. In Arnhem Land (Northern Territory), the Yolngu people tell of the Djang’kawu (also spelled Djanggawul) – a brother and two sisters who are creation ancestors that populated the land. The word Djang in their language carries the sense of creation power; the Djang’kawu sisters create freshwater wells and give birth to the first people. Many clans in that region incorporate “djanggawul” or related syllables in their clan names – for instance, the Rirratjingu clan (note “jingu” ending) traces lineage to those creator beings. In other Australian languages, we find Quinkan (or Quinkun), the name for spirit-ancestors in Queensland rock art traditions, and Wandjina, the cloud-and-rain spirits painted in the Kimberley region. Wandjina ends in -jina, and these beings are revered as givers of life and law (their images have halo-like faces with no mouths, surrounded by lightning). While the etymology of Wandjina isn’t clear, it’s fascinating that it contains jina, a sound that elsewhere can mean “spirit” or “conqueror” (as in the Sanskrit Jina). The Aboriginal Yuin people, in the south-east of Australia, have a word Moojingarl for an individual’s personal totem spirit – notice jing in the middle of that term. Even the everyday word “gin” in older Australian English (a now-offensive term for an Aboriginal woman) derives from the Dharug word diyin meaning “woman”. It’s a curious footnote that diyin in Dharug sounds like djinn, but here it meant a human female rather than a spirit; still, it shows how widely the jin phoneme appears. Taken together, Aboriginal Australian languages and myths contribute strong evidence for the Jing hypothesis: they have both the conceptual link (snakes = creators of life, wells = sources of spirit, etc.) and the linguistic link (words like Waug, Djang, jinga that coincide with the sounds for spirit elsewhere). Considering that Aboriginal traditions could have been isolated for over 40,000 years, such parallels might point to an extremely ancient inheritance – potentially carried by the first humans to leave Africa. It’s as if the original “breath-soul” snake deity left an imprint in the Dreamtime stories that endures to this day.

Other Notable Parallels – Beyond the above, there are countless smaller echoes that make one wonder if a global layer of religion and language once existed. In Africa, for example, the name of the Dinka people of Sudan comes from what they call themselves, Jiëŋ (with a j-sound). Could it be that Jieŋ simply meant “the People” originally – akin to saying “we who have jin/spirits”? The word Bantu (a huge family of African languages) means “people” in many of those tongues, but a legend says the first man in some Bantu mythologies was Kintu – interestingly, kintu means “thing” in some languages, and was used to refer to people without dignity. This resonates with the idea that having a spirit (or failing to have one) defined personhood – those who lost their spirit became mere “things”. Even in Europe, traces of a similar notion exist: for instance, the word “kind” (as in mankind or kindred) comes from Old English gecynd and Old Germanic kundjaz, from that same PIE root gen- – implying that to be human is to be of the kin, born of the spirit. The English word “king” is thought to derive from kin (hence king originally meaning “leader of the kin”) and indeed one theory is that king comes from a term for “scion of a divine race”. If ancient kings were seen as descended from serpent-gods or sky-fathers (as many myths claim), then even king has a conceptual tie: the king was the living gene, the lineage from the gods. In Mongolian, the title of the great conqueror Genghis Khan was originally Chinggis Khan, pronounced closer to “Jinggis”. Some scholars interpret Chinggis as meaning “of strong power,” but the exact etymology is debated. It’s tantalizing that Jinggis echoes Jinn/genius – especially since Genghis Khan’s clan name Borjigin may contain -jigin, and one analysis of Borjigin noted it related to legends of blue wolves and deer (animals laden with spiritual symbolism in Mongol lore). Finally, even at the level of sound symbolism, one might ask: do the letters G-N (or J-N) often attach to profound concepts by sheer chance? For example, “knowledge” (Latin gnosis) has that gn-; the “gnostic” was one who knew the spiritual secrets. The syllable OM/AUM gets a lot of attention as a sacred sound, but perhaps GEN was an equally sacred syllable in the forgotten past.

Conclusion: A Lost Word for the Soul?#

Drawing all the threads together, the Jing hypothesis paints a picture of an archaic spiritual vocabulary that could underlie many modern words. It suggests that countless terms for soul, spirit, personhood, kinship, creation, and even deity names are not isolated accidents, but fragmented relics of an ur-language of the psyche. We see recurring elements: serpents that breathe life, hidden spirits that guide and inspire, and the breath or essence inside us that defines life. The hypothesis boldly claims that these were once encapsulated in a single root word – perhaps something like “djinn” or “jing” – spoken by our remote ancestors.

How do linguists view this idea? Mainstream historical linguistics typically explains similarities through known language families (Proto-Indo-European *gen-, Semitic *jnn, etc.) or borrowing between cultures (for instance, the Romans influencing the Middle East gave us the jinn-genius overlap). There’s no acknowledged single root that spans all humanity’s tongues; in fact, traditional theory holds that language has multiple independent origins. However, it’s not completely far-fetched that very ancient humans shared some common religious terms. Academic support for pieces of this theory can be found in comparative mythology: for example, researchers have long noted the “Rainbow Serpent” myth is widespread from Australia to Africa, hinting at great antiquity. And certain deep-rooted words do appear in many unrelated languages (some scholars call them “ultraconserved words”). The idea of a 15,000-year-old word for mother or not has been entertained by linguists; why not a 15,000-year-old word for soul? If such a word exists, jing/gen is a compelling candidate, given how globally it echoes.

Ultimately, the Jing hypothesis remains a highly intriguing speculation – a kind of grand unified theory of ancient spirit-language. It encourages us to look at familiar words with fresh eyes: genius, generate, imagine, jing, jinn, king, kindred… are these merely coincidental phonetics, or whispers of a forgotten mother tongue of myth? We may never know for sure. But exploring these connections enriches our appreciation of human culture. It reminds us that mythology, linguistics, and early consciousness are interwoven. Even if one is skeptical, it’s hard to deny the poetic appeal: somewhere in the mists of prehistory, as humans everywhere gazed at snakes and stars in wonder, perhaps they spoke a common word to name the mysterious thing that breathes within us. That word – whether jing, jinn, gen, or something similar – would be nothing less than the name of the soul itself, passed down in tales and tongues through the ages. And that is a thought as enchanting as any genie’s spell.

Sources#

- Mallory, J.P. & Adams, D.Q. (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford University Press. [PIE *gen- root analysis]

- Partridge, Eric (2006). Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. Routledge. [Genius, genesis, and related etymology]

- Lane, Edward William (1863). An Arabic-English Lexicon. Williams & Norgate. [Classical Arabic jinn etymology]

- Eliade, Mircea (1964). Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton University Press. [Serpent symbolism in early religion]

- Dixon, R.M.W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Cambridge University Press. [Aboriginal Australian linguistic analysis]

- Watkins, Calvert (2000). The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots. Houghton Mifflin. [Comprehensive IE root dictionary]

- Campbell, Joseph (1959). The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology. Viking Press. [Global serpent cult parallels]

- Benveniste, Émile (1973). Indo-European Language and Society. University of Miami Press. [Social concepts in IE languages]