TL;DR

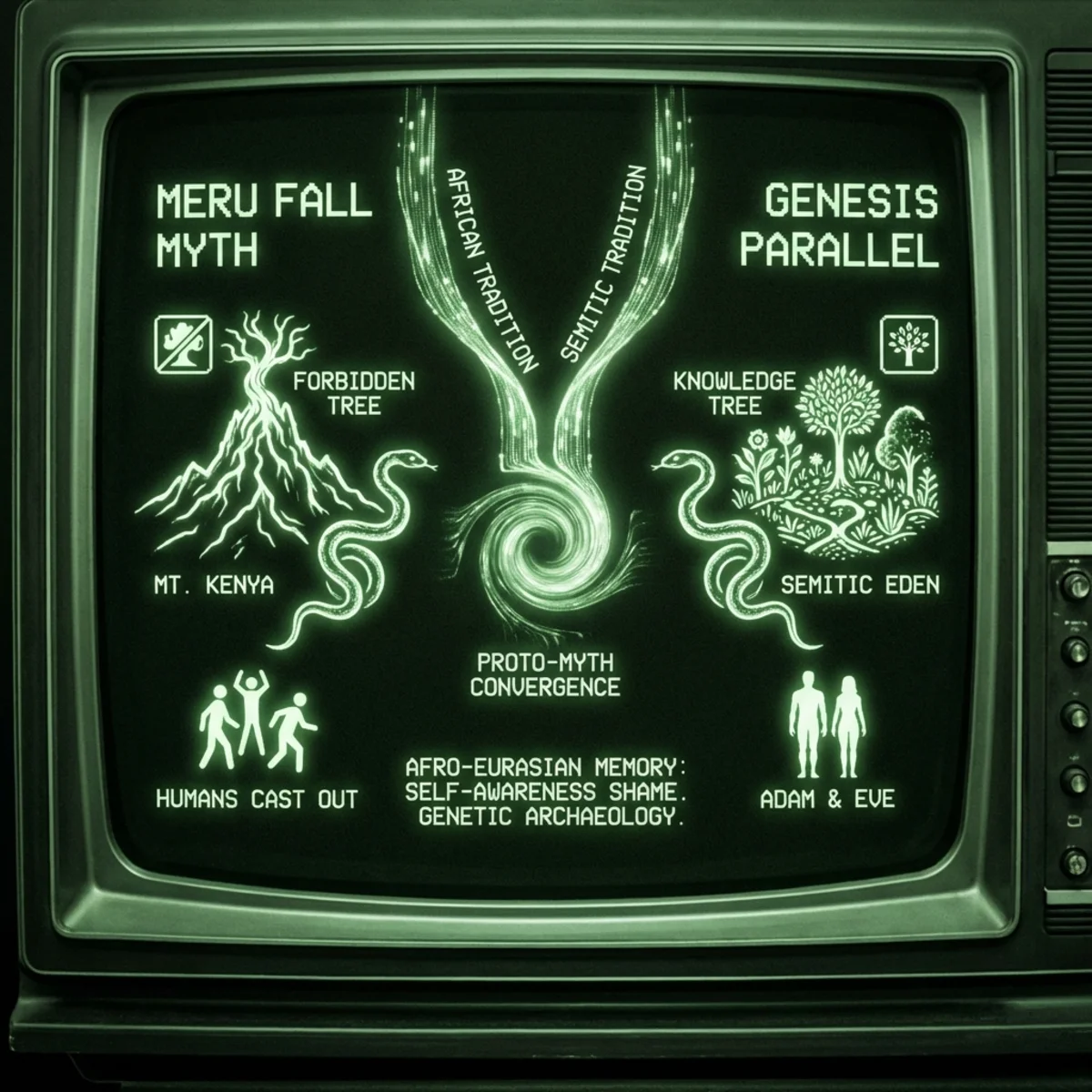

- The Meru people of Kenya have an oral creation myth remarkably similar to the biblical Genesis “Fall of Man”: a creator god (Murungu), first humans in paradise (Mbwa), a forbidden tree, a wise serpent tempter, and loss of immortality/innocence after transgression.

- This paper compares the Meru myth with parallels in ancient Near Eastern (Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, Adapa myth, Genesis), Egyptian, and other African (Cushitic, Bantu, Khoisan) traditions.

- Motifs like the serpent associated with wisdom/trickery, sacred trees linked to divinity/life, and the loss of a perfect state are widespread, suggesting deep historical roots or cultural diffusion.

- Possible transmission routes for the Eden-like narrative into Meru lore include ancient Semitic/Judaic contact in Northeast Africa, later Islamic influence via coastal trade, or recent syncretism with Christian missionary teachings.

- While direct missionary influence is plausible, the presence of ancient analogues and local adaptations (Murungu as God, sacred fig trees) suggests the Meru myth likely represents a blend of introduced Abrahamic elements with indigenous African cosmology.

Introduction#

The Meru people of Kenya preserve a creation myth that strikingly resembles the biblical “Fall of Man.” It centers on Murungu – the Meru supreme being – a forbidden tree, a wise serpent, and the tragic consequences of human disobedience. Such motifs are not unique to the Meru; comparable elements appear across Afro-Eurasian mythologies, from ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt to Cushitic Africa. This paper examines the Meru narrative of the Fall in detail and compares it with similar myths in other traditions. It explores whether the Meru story might reflect influences from much earlier Bronze or Iron Age myths (e.g. ancient Near Eastern) rather than being a late borrowing from Christian teaching. Possible pathways of transmission into Meru oral tradition – via trade contacts, migration and intercultural exchange, or religious syncretism – are discussed. Pre-Christian parallels in Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Cushitic, and early Semitic lore will be analyzed to evaluate the antiquity and origins of this narrative.

The Meru Creation Myth of Murungu and the Forbidden Tree#

According to Meru oral tradition, in the earliest times humans lived in a paradisiacal realm called Mbwa (or Mbwaa) where they neither cultivated food nor wore clothing . Murungu (also known as Ngai or Mwene Nyaga in related Kenyan cultures) is the supreme creator god in Meru cosmology . Murungu first created a boy, and seeing him lonely, then created a girl; the two became the first man and woman, who bore a child . Murungu provided for their needs and gave them all foods except the fruit of one specific tree which He forbade them to eat . This tree stood as a divine taboo, much like the Tree of Knowledge in the biblical Eden.

A serpent, described in Meru lore as a wise and shrewd creature, approached the first woman and spoke of the forbidden fruit’s secret . The snake enticed her with a bold promise: if she ate the fruit, she would attain the intelligence of God (i.e. become as wise as the Creator) . Swayed by the serpent’s cunning words, the woman plucked a fruit from the forbidden tree and ate. She then offered it to her husband. Initially the man refused, but after his wife’s urging, he too ate the fruit in defiance of Murungu’s command . In that moment of disobedience, the primordial innocence and harmony were shattered.

Though details vary in retellings, Meru elders say that the immediate consequence was that humans could no longer live effortlessly as before. Having broken Murungu’s command, the first people now found themselves needing to eat, work, and clothe themselves, whereas previously Murungu had directly sustained them . In effect, by acquiring god-like knowledge illicitly, they lost the god-given privileges of their original state. This closely parallels the outcome in Genesis, where Adam and Eve become aware of their nakedness and are cursed to toil for food. In Meru mythology, humanity’s disobedience incurred Murungu’s displeasure and led to suffering and mortality entering the world. The myth thus serves as an etiological tale explaining why humans must labor, feel shame, and face death, attributing it to an ancestral fall from grace.

It is important to note that Murungu in Meru belief is conceptually similar to the High God of neighboring peoples (for example, the Kikuyu and Kamba also call the creator Ngai/Mulungu and associate Him with sacred trees)  . The Meru share regional cosmological concepts, yet the forbidden tree and serpent story is a particularly salient piece of their oral literature. Some scholars have raised the question of how an Eden-like narrative took root among the Meru. Was it purely a product of 19th–20th century missionary influence, or could it have much older origins, transmitted through ancient interactions? To explore this, we must compare the Meru story’s motifs with those in other Afro-Eurasian myths.

Parallels in Afro-Eurasian Mythological Traditions

Ancient Mesopotamian Parallels#

Elements of the Meru “Fall” myth – a divine tree, a trickster serpent, and lost immortality/innocence – evoke themes found in some of the world’s oldest recorded myths from Mesopotamia. For instance, the Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 18th–12th century BCE) contains a famous episode in which the hero Gilgamesh obtains a sacred plant that can rejuvenate life, only to have it stolen by a serpent. As Gilgamesh bathes, “a serpent discovered the whereabouts of the plant through its smell and swallowed it, slithering away. When Gilgamesh saw what had happened he…sat down and wept,” realizing his chance at immortality was gone. The snake’s theft of the plant of life in the Mesopotamian epic directly “stole the attainment of eternal life from Gilgamesh”. This ancient tale reflects a similar motif to the Meru story: a wily serpent causes humanity (personified by Gilgamesh) to be deprived of eternal life. In Gilgamesh, the serpent’s shedding of its skin afterward is a symbolic sign of renewal – the snake rejuvenates while man is left mortal. The Meru myth likewise explains how humans lost their carefree, immortal existence due to heeding a snake’s counsel. Both stories imply that but for the serpent’s intervention, humans might have lived forever or in divine bliss.

Another Mesopotamian parallel is the myth of Adapa, a wise man created by the god Ea (Enki). Adapa is offered the food and water of immortality by the sky-god Anu, but – having been tricked by Ea – he refuses to consume them. As a result, Adapa misses his chance at eternal life. In this tale, “the food and drink of eternal life are set before him; [Adapa’s] over-caution deprives him of immortality, [and] he has to return to Earth” as a mortal. Scholars often regard Adapa’s story as a Mesopotamian “Fall of Man” myth that explains why humans remain mortal despite divine offers of life. The logic is inverted compared to Meru/Genesis – Adapa’s obedience to a deceptive command causes his downfall – yet the core theme is the same: humanity fails a test involving divine food and thus cannot live forever. In both the Adapa myth and the Meru story, a being with greater knowledge (Ea in Adapa’s case, the serpent in the Meru tale) guides humans in a way that ultimately prevents them from attaining god-like life. These Mesopotamian examples predate biblical Genesis by many centuries, suggesting that the motifs of a forbidden life-giving substance and a trickster figure were part of the Near Eastern cultural repertoire long before Christianity. It is conceivable that echoes of these could have traveled through oral diffusion into Africa in antiquity.

Early Semitic and Biblical Tradition#

The closest analogue to the Meru creation story is found in the Semitic tradition of the Garden of Eden in the Hebrew Bible (Genesis 2–3). The parallels are unmistakable: in Eden, God places the first man and woman in a paradise where they need not toil, prohibits them from eating the fruit of a certain tree (the Tree of Knowledge), and a crafty serpent convinces the woman (Eve) to eat the forbidden fruit, who then gives it to her husband (Adam). As in the Meru myth, the humans disobey, seeking wisdom to be like God, and this act of disobedience brings about dire consequences – loss of innocence, expulsion from paradise, the onset of labor, shame, and death. The Meru phrase that the serpent promised the woman she would have “the intelligence of God” mirrors the serpent’s claim in Genesis 3:5 that “your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.” After the transgression, both accounts emphasize that humans must now fend for themselves. In Genesis, God himself notes that man has gained forbidden knowledge and banishes him “lest he put forth his hand and take also of the Tree of Life, and eat, and live forever”. Likewise, in Meru lore humans were originally free from hunger and death, but after eating the sacred fruit they lose those gifts. In effect, in both stories humanity is prevented from attaining immortality or remaining in a blissful state due to an act of defiance.

The Eden story is widely known to have ancient Near Eastern antecedents. Mesopotamian influence is likely – for example, the Edenic serpent can be compared to the one in Gilgamesh, and the concept of a forbidden knowledge might be linked to Mesopotamian wisdom traditions. Genesis was compiled in the Iron Age (traditionally sometime between 10th–6th century BCE), drawing on even older oral and written sources. Therefore, the idea of a primeval paradise lost could have been transmitted through Semitic cultures well before Christianity ever reached sub-Saharan Africa. It is conceivable that early Semitic traders or migrants brought versions of this narrative into Africa in antiquity. For instance, ancient Semitic-speaking peoples (Sabaeans and others) had a presence in the Horn of Africa (Ethiopia/Eritrea) by the first millennium BCE. Jewish communities (later known as Beta Israel or Falasha in Ethiopia) have existed for over 2000 years in East Africa, preserving Old Testament stories. If the ancestors of the Meru had contact with such groups, they might have absorbed the Edenic myth long ago. In fact, one hypothesis suggests the Meru people descend from migrants who came from the north: “the Meru could be descendants of the black Jews called Falasha, who lived near Lake Tana in the land of Meroë” (ancient Nubia/Ethiopia). While this theory is speculative, it illustrates that scholars have entertained an ancient Northeast African link for Meru traditions. Such a connection, if true, would mean the Meru Fall myth could have entered their culture via early Judaic or Semitic lore rather than direct European missionary influence.

Even within Africa, the idea of a lost paradise due to human fault is not unique to Meru. The theme of disobedience against the creator leading to death appears in various African traditional myths (which may or may not have been affected by Abrahamic religion). For example, the Mbuti (Efe) people of the Congo tell of the supreme god Arebati who forbade a woman to eat from a certain taboo tree; when she did so, Arebati punished humanity with death. Similarly, the Acholi of Uganda say God (Jok) initially intended to give humans the fruit of the Tree of Life to make them immortal, but humans failed to receive it in time and lost that chance. These stories, while not involving a serpent, echo the pattern of a divine test or prohibition resulting in mortality for mankind. They could be independent developments – a reflection of how many cultures grappled with explaining death – or they too may have been influenced by older Eurasian tales of a fall from grace. The Meru myth, with its serpent tempter, aligns even more closely with the Judeo-Christian version than most African variants do. This raises the possibility that it was shaped by relatively recent contact with Bible stories. Yet, as shown, the ingredients of the tale (tree of knowledge, snake, forbidden fruit) all have much older analogues in the Near East. The question remains: through what route did those motifs reach the foothills of Mount Kenya?

Egyptian and Cushitic Parallels#

In the ancient Egyptian worldview, there is no exact equivalent of the Eden story, but there are notable analogues of the serpent and sacred tree motifs. The Egyptians venerated the figure of the serpent in multiple forms – sometimes benevolent, sometimes malevolent. A serpent (the cobra uraeus) was a symbol of royal wisdom and divine protection, often depicted on the pharaoh’s crown, and goddesses like Wadjet took serpent form. Conversely, a giant malevolent serpent Apophis was seen as the enemy of the sun-god Ra, representing chaos and having to be defeated daily. While Egyptian mythology doesn’t describe a first man and woman being tricked by a snake, it does tell of humanity’s early rebellion against the Creator: in the “Destruction of Mankind” myth, humans conspire against Ra, and as punishment the eye of Ra (as the fierce goddess Hathor) slaughters humanity until Ra relents. This is a different scenario (a flood-like punishment story) but reflects the theme of primeval disobedience leading to disaster. Notably, Egyptian lore also had the concept of a sacred tree that grants knowledge or life – for example, the mythical sycamore Tree of Life at Heliopolis, upon whose leaves the gods inscribed the pharaoh’s fate. In one Egyptian legend, the goddess Isis gains supreme power by tricking the sun-god Ra into revealing his secret name – and she does so by fashioning a magical serpent that bites him, forcing him to yield his knowledge. Here we see a serpent used as an instrument to obtain divine knowledge, analogous to how the Meru serpent helps humans steal divine wisdom. Such narratives underscore that in Northeast Africa and the Near East, serpents were often associated with wisdom, cunning, and the boundary between divine and human realms.

Turning to the Cushitic and Horn of Africa traditions, we find extensive serpent symbolism that could form a backdrop for a story like the Meru Fall. Pre-Christian religions of the Horn (e.g. among Oromo, Somali, and other Cushitic peoples) frequently venerated serpents and sacred trees. Ethnographic records note that many communities in southern Ethiopia had snake cults and tree shrines. In fact, early Ethiopian Christian hagiographies recount saints destroying “snakes that were held in great esteem by the local population and cutting down the trees in which they lived”. This implies that rural peoples worshiped serpent spirits residing in certain trees – a clear parallel to the serpent-and-tree motif. A Ge’ez (Ethiopian) legend of King Arwe speaks of a giant serpent who once ruled as a tyrant before being slain by a culture hero, reflecting the “centrality of the Serpent in many pre-Christian religions of the region”. Moreover, several Cushitic groups have origin myths involving serpents. The Konso and Boorana (Oromo) tell of ancestral women impregnated by mystical snakes, from whom clans descend. One Oromo oral tradition even traces the tribe’s origins to a great snake from the sea that led them to their homeland. In these traditions, the serpent is a progenitor or guide—often a positive force bestowing fertility or land. The ambivalence of the serpent in African myth (sometimes a giver of life/wisdom, other times a deceiver or adversary) is very much in evidence.

What these Egyptian and Cushitic examples demonstrate is that long before any Christian missionary arrived, African cultures already attributed deep significance to serpents and sacred trees. A “wise serpent” in a sacred tree would not have been a foreign concept to the Meru. In their own environment around Mount Kenya, the Meru and related peoples held certain fig trees (mugumo trees) to be holy dwelling places of God (Murungu/Ngai). Indeed, elders made sacrifices under sacred fig trees and believed divine messages could be pronounced there. It is intriguing, then, that in the Meru Fall myth the very site of transgression is a special tree provided by God. This resonates with the local reverence for trees as bridges between heaven and earth. It may be that when the motif of a forbidden tree arrived (from whatever source), it found fertile ground in Meru culture, aligning with pre-existing arboreal symbolism. Likewise, a serpent imparting secret knowledge might have been syncretized with indigenous snake beliefs. Rather than seeing the Meru myth as a verbatim copy of Genesis, we can interpret it as a creative fusion of an introduced narrative with traditional Meru cosmology – Murungu takes the role of the biblical God, the fig (or other sacred tree) becomes the Tree of Knowledge, and the wise serpent fits both the biblical tempter archetype and the African notion of the serpent as a guardian of mysteries.

Transmission Pathways: Ancient Influence or Missionary Era?#

Did the Meru myth of the Fall come down through the ages from Bronze/Iron Age contacts, or was it a product of more recent missionary influence? The truth may involve a bit of both, and scholars offer several scenarios:

- Direct Missionary Introduction (19th–20th Century): European missionaries began evangelizing East Africa in the late 1800s (the Meru highlands saw Catholic Consolata missionaries by 1902 ). It is highly plausible that the Eden story was taught to Meru converts and then entered oral circulation, being “indigenized” over time. Missionaries often deliberately drew parallels to indigenous beliefs to facilitate conversion. For example, some early clergy in Kikuyu-land preached under sacred fig trees and likened Ngai (the high God) to the Christian God  . The Meru could have grafted the new story onto their own framework: Murungu was equated with the Christian Creator, and the missionaries’ tale of Adam and Eve was retold in Meru idiom (with the first humans located at Mbwa, and perhaps the forbidden tree imagined as a familiar fig tree). If this is the case, the Meru “Fall” myth might be only a century or so old in its current form. Some evidence supports recent adoption – for instance, the explicit notion of a wise serpent imparting godlike knowledge is uncommon in older African folklore but matches the biblical narrative. Additionally, early colonial-era recordings of Meru myths (if any exist) do not prominently mention this Fall story, which might indicate it crystalized in the oral tradition during the colonial period under Christian influence.

- Islamic or Pre-Christian Abrahamic Influence: Long before European missionaries, the East African coast had interactions with the Islamic world. By the 1700s (and earlier), Swahili and Arab traders who were Muslim could have relayed Quranic/Biblical stories inland. The Meru, in their own oral history, say they were once enslaved on an island called Mbwaa by “red people” (likely Omani Arab slavers) around the 1700s before escaping to the mainland  . During that period of servitude or contact, Meru ancestors might have learned elements of Judeo-Christian-Islamic lore. The Adam and Eve story is also part of Islamic tradition (taught in the Quran, with only minor differences). Thus, the forbidden fruit narrative may have trickled into Meru consciousness via Islamic folklore told by coastal peoples, prior to intensive Christian mission. This would place the adoption in the eighteenth or early nineteenth century, still not “Bronze Age” but pre-dating direct missionary teaching. It’s worth noting that many African societies that had early contact with Islam (for example, the Hausa or Swahili) absorbed biblical/Quranic tales into their oral literatures. The Meru could likewise have received the Fall story secondhand in this way and then adapted it to fit Murungu and Mbwa.

- Ancient Diffusion via Cushitic Migration or Nilotic intermediaries: Another intriguing possibility is that versions of the paradise-loss myth spread south during much earlier migrations – for instance, through Cushitic-speaking peoples moving into Kenya. Linguistic and genetic evidence shows that Cushitic pastoralists from Ethiopia moved southwards into Kenya and Tanzania during the late Bronze and Iron Ages (1000 BCE – 500 CE) and again around 1000–1500 CE. These people (ancestors of Somali, Oromo, Rendille, etc.) would have carried their belief systems, some of which (as shown) featured serpents and perhaps had exposure to Near Eastern ideas. Similarly, Nilotic peoples (like the Luo and others) migrated from the Nile Valley into East Africa, potentially bringing stories influenced by Sudanese Nubia or Abyssinia. If the Meru’s ancestors encountered or intermarried with such groups, they might have inherited mythic motifs of northern origin. The speculation connecting Meru to Meroë (ancient Nubia) and to Beta Israel (Ethiopian Jews), while not mainstream, aligns with the notion of an older cultural transfer . Under this scenario, fragments of an Eden-like tale could have been known in East Africa centuries ago, perhaps in a fragmented form (e.g. “a long time ago, a woman was tricked into breaking God’s rule by a snake, and thus death came into the world”). The full-fledged narrative as we have it now might have coalesced later, but its building blocks would be ancient. This is difficult to prove without early documentation of the tale, yet the convergence of Meru, Congolese, and Sudanese origin-of-death myths suggests a deep shared layer of African mythology that could have synergized with incoming Eurasian ideas. Anthropologists note that many African creation myths do contain a “lost gift” or “failed message” motif wherein humans could have had immortality but missed out due to a trick or error  . This widespread motif may be indigenous, but its resonance with the Eden story is clear. It might have eased the incorporation of an explicit forbidden-fruit narrative when contact with Abrahamic religions occurred.

- Independent Emergence (Convergent Tradition): Lastly, one must consider human imagination’s convergent development. It is possible, though perhaps less likely, that the Meru independently developed a tale so similar to the Near Eastern one simply because the themes of temptation and fall are universally meaningful. Human cultures across the world have devised myths to answer “why do we die, why do we suffer, why is the world imperfect?”; a trope of an original sin or mistake is a common answer  . The presence of a wise animal or trickster is also a common folkloric element globally. In sub-Saharan Africa, many myths feature trickster animals (like the hare or spider) who upset the established order. A snake could fill that role. And sacred trees are objects of reverence in many cultures for their life-giving fruits or healing properties. Thus, the Meru might have logically woven these together on their own. However, the specificity of the parallels (forbidden fruit, serpent, man and woman, seeking God’s wisdom) leans toward some form of cultural transmission rather than pure coincidence. Unlike the generic “failed message of immortality” tale (chameleon vs. lizard, etc., which is widely independent  ), the Meru version’s structure is virtually identical to the Genesis account, which makes independent invention improbable without influence.

Considering all the above, the most plausible explanation is a combination: the Meru Fall myth likely entered their oral tradition during the last few centuries as a result of syncretism – the blending of an introduced Abrahamic tale with longstanding local beliefs about God (Murungu), sacred trees, and serpents. The narrative as recorded in the 20th century shows a thoroughly Meru character (using Meru names and setting) but carries an uncanny echo of ancient Afro-Eurasian wisdom lore. In essence, the Meru elders made the story their own, whether they learned it from missionaries, travelers, or distant ancestors.

Conclusion#

The Meru story of Murungu’s forbidden tree and the wise serpent exemplifies how a powerful mythic motif – the Fall of humankind – transcends cultures and epochs. In Meru oral lore, we see a local African iteration of a tale that also appears in the Hebrew Bible and has roots in Mesopotamian legend. The core elements of a paradisal beginning, a divine prohibition, temptation by a serpent, and the loss of innocence and immortality link the Meru to a vast mythological tapestry spanning Africa, the Near East, and beyond. While on the surface the Meru myth closely parallels the Genesis account (suggesting a historical influence from Judeo-Christian sources), its deeper context resonates with indigenous African religious concepts (sacred trees and serpents as conveyors of power). This raises the tantalizing possibility that the Meru Fall narrative is not merely a colonial-era borrowing, but the product of a longer-term cultural dialogue between Africa and the ancient world. Whether transmitted through Bronze Age trade routes, Cushitic migrations, or missionary Bibles, the myth found enduring relevance among the Meru by addressing universal questions of obedience, knowledge, and mortality.

Ultimately, the Meru myth of the Fall stands as a testament to the adaptability and continuity of myth. It absorbed influences from abroad while reflecting local sensibilities – for example, portraying the serpent in a somewhat ambivalent light as “wise” rather than purely evil, and placing the first humans in a locale (Mbwa) significant to Meru history. The comparative evidence strongly suggests that the story’s motifs are ancient, even if the Meru may have learned the full narrative relatively recently. In myth as in language, traces of long-forgotten contacts can survive in new forms. The forbidden fruit of Meru tradition may thus be seen as a fruit of many branches – a story with roots in the oldest civilizations, grafted onto the living tree of Meru culture through the winds of time.

FAQ#

Q1. How similar is the Meru myth to the biblical Garden of Eden story?

A. The parallels are striking and specific: both feature a creator god, first humans in paradise, a forbidden tree, a wise serpent tempter, human disobedience, and loss of immortality/innocence. The Meru version locates the events at Mbwa (a sacred island) and uses Murungu as the god, but the core structure – temptation by serpent leading to fall from grace – is virtually identical to Genesis 2-3, suggesting either direct influence or shared ancient motifs.

Q2. Could the Meru myth be entirely indigenous without biblical influence?

A. While possible, it’s unlikely due to the specificity of the parallels. African cultures have many creation myths, but the exact combination of forbidden fruit, serpent as trickster/wisdom figure, and loss of immortality is uncommon in purely indigenous African folklore. The motif appears more prominently in Afro-Eurasian traditions with known Near Eastern connections, suggesting some form of cultural transmission rather than independent convergence.

Q3. When and how might the Eden-like narrative have reached the Meru people?

A. Several pathways are possible: (1) Recent Christian missionary influence (19th-20th century), (2) Earlier Islamic transmission via coastal trade (18th century), or (3) Ancient diffusion through Cushitic migrations from Ethiopia (Iron Age to medieval period). The most plausible scenario is a combination – early fragments entering through trade/migration, then crystallized through missionary contact, with local adaptations making it distinctly Meru.

Q4. What does this comparison tell us about the spread of mythological motifs?

A. It demonstrates how powerful mythic narratives can travel across cultures and continents, adapting to local contexts while preserving core elements. The serpent-wisdom-forbidden knowledge motif appears in Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and various African traditions, suggesting either very ancient shared origins or extensive cultural diffusion. The Meru case shows how such stories can be successfully indigenized, blending introduced elements with local cosmology (Murungu, sacred trees).

Sources#

(Note: Citations in the text likely correspond to these sources, but the mapping was lost. The list below is derived from the original bibliography and table.)

- Scheub, Harold (ed.). A Dictionary of African Mythology: The Mythmaker as Storyteller. Oxford University Press, 2000. (Source for Meru myth summary). URL:

https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofafri00sche - Lynch, Patricia Ann; Roberts, Jeremy. African Mythology A to Z (2nd ed.). Chelsea House, 2010. (Context on African creation/origin-of-death myths).

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator & editor). The Babylonian Story of the Deluge and the Epic of Gilgamesh. Harrison & Sons (London), 1920 (Eng. trans.). (Context for Gilgamesh serpent/immortality motif). URL:

https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/budge-the-babylonian-story-of-the-deluge-and-the-epic-of-gilgamesh - Mark, Joshua J. “The Myth of Adapa”. World History Encyclopedia, 2011 (online). (Context for Adapa myth). URL:

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/216/the-myth-of-adapa/ - Sewasew Encyclopedia editors. “Serpent(s)” (encyclopedia entry). Sewasew.com, ≈2021. (Context for Northeast African serpent/tree symbolism). URL:

https://en.sewasew.com/p/serpent%28s%29 - Karangi, Matthew Muriuki. Revisiting the Roots of an African Shrine: The Sacred Mugumo Tree. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2013. (Context for Kikuyu/Meru sacred tree beliefs). URL:

https://imusic.co/books/9783659344879/ - Shanahan, Mike. “What happened when Christian missionaries met Kenya’s sacred fig trees”. Under the Banyan (blog post), 11 Apr 2018. (Context on missionary encounters with sacred trees). URL:

https://underthebanyan.blog/2018/04/11/when-happened-when-christian-missionaries-met-kenyas-sacred-fig-trees/ - Fabula Journal. “Myth as a Historical Basis of the Meru Folktales”. Fabula 43 (1‐2): 35‐54, 2002. (Academic article discussing Meru origins/influences). URL:

https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.2002.022 - Hebrew Bible (traditional Mosaic authorship). Genesis 2 – 3 (Garden of Eden narrative). ≈6th c. BCE compilation. (Source text for comparison). URL:

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Genesis+2-3&version=NRSVUE