TL;DR

- Gap - Anatomically modern brains appear ~200 kya, but symbolic culture blooms ~50 kya.

- Ritual trigger - Froese: altered-state initiations forge subject-object separation.

- Concrete mechanism - Eve Theory: female-led snake-venom rites spread the “self” meme, leaving mythic and genomic traces.

- Pay-off - Combined model outperforms gradualist, saltationist, and generic “stoned-ape” accounts.

1 Introduction - Why the Sapient Paradox Persists#

One of the enduring puzzles in human evolution is the Sapient Paradox – the disconnect between the early emergence of anatomically modern humans and the much later blossoming of fully “human” behavior . In other words, if our species was biologically modern by ~200,000 years ago, why did symbolic cognition, art, religion, and science only proliferate tens of millennia later? This gap hints that the mere possession of a modern brain was not sufficient; some additional catalyst was needed to spark reflective consciousness and the rich symbolic culture that defines humanity. Cognitive scientist Tom Froese has tackled this foundational problem by proposing the Ritualized Mind Hypothesis, which posits that cultural ritual practices – especially those inducing altered states of consciousness – played a decisive role in establishing the subject–object separation required for symbolic thought . Building on Froese’s insight, the Snake Cult of Consciousness (also known as the Eve Theory of Consciousness) has emerged as a bold synthetic model that extends his ideas across multiple disciplines. The Eve Theory argues that the concept of the self (the subjective “I”) was discovered in prehistory and then taught and spread via ritual, with snake venom-induced trance as a key enabler . This paper presents a deep synthesis of Froese’s theory and the Eve Theory, showing that the Snake Cult/Eve model is the natural and most developed extension of Froese’s hypothesis. We compare this integrated perspective to alternative accounts of the origins of human consciousness, demonstrating that it more comprehensively fulfills the explanatory goals – bridging cognitive science, anthropology, semiotics, evolutionary biology, religious studies, and psychometrics. In doing so, we position Froese’s ritualized mind as solving a critical evolutionary puzzle, and the Eve Theory as providing the most empirically fertile articulation of that solution.

2 Froese’s Ritualised-Mind Hypothesis: Symbolic Cognition through Altered States#

A fundamental challenge in cognitive evolution is explaining how early humans became capable of abstract, symbolic thought and true self-awareness. Froese identifies the emergence of an observer stance – a clear distinction between subject and object, self and world – as the key cognitive shift. Modern humans take this dualistic consciousness for granted (we conceive of an “I” separate from what is perceived), but our hominin ancestors primarily experienced the world through what Heidegger called Dasein, an immersive “being-in-the-world” without reflective distance. Froese’s model suggests that some mechanism was needed to break our ancestors out of this immersive mode and induce a reflective, detached mode of awareness. Crucially, he proposes that ritualized induction of altered states was that mechanism. By deliberately disrupting ordinary consciousness – through intense rituals – early humans could trigger episodes of self-awareness and gradually stabilize a new cognitive trait.

Ritual practices in the Upper Paleolithic, according to Froese, functioned as a kind of “cognitive technology” to produce subject–object separation for initiates. These rites closely resemble what anthropologists observe in traditional initiation ceremonies: they often involved prolonged sensory deprivation (e.g. darkness and silence in deep caves), extreme physical hardships and pain, enforced social isolation, and ingestion of psychoactive substances. Such ordeals – frequently timed with puberty rites – have little to do with physical maturation per se, but are enormously effective at perturbing normal consciousness. Neurologically, these interventions disrupt the usual sensorimotor loops and can induce hallucinations and out-of-body experiences. In Froese’s enactive cognitive framework, this forced disruption pushes the brain into an unusual state where the normal unity of perception and action collapses, allowing an incipient objectifying consciousness to surface. In effect, the initiate is brought to a phenomenological crisis – “to the edge of death” – wherein they discover a “residue of awareness” that seems to persist independent of the body. This visceral demonstration of the self as separate from the body (a pedagogy by practice, “show, don’t tell” as Froese puts it) was pivotal in cultivating stable metacognition. Through repeated cultural iteration, such practices could transform a once fleeting insight into an expected ontogenetic stage of development: every adolescent’s mind was ritualistically re-shaped into a more dualistic, reflective form suited for enculturation into symbolic culture.

Over time, the need for intense ritual may have diminished as genes and culture co-evolved. Once a reflective, symbol-ready mindset became widespread, human development and socialization alone could reinforce it without always resorting to drastic rites. The first symbolic expressions left in the archaeological record support Froese’s scenario. The earliest known forms of art from anatomically modern humans – abstract geometric engravings and patterned cave paintings dating ~70–40 thousand years ago – strongly resemble the entoptic patterns (grids, zigzags, dots) produced in early stages of trance hallucination. Researchers like Lewis-Williams had long theorized that Upper Paleolithic cave art was linked to shamanic visions; Froese’s contribution was to embed this in an evolutionary “ritual as incubation” model of cognitive development. In short, cultural rituals provided the scaffolding for the emergence of human symbolic consciousness. This hypothesis offers a compelling resolution to the Sapient Paradox: ritualized mind alteration was the catalyst that turned anatomically modern humans into behaviorally and cognitively modern humans. Rather than a mysterious genetic mutation suddenly granting symbolic thought, Froese’s model suggests an interactive process – our ancestors bootstrapped their own minds through cultural practices, and subsequent natural selection then reinforced those mental capacities. As Froese and colleagues argue, this model “solves many of the issues related to human evolution” by explaining how reflective consciousness could arise relatively abruptly in the late Pleistocene and then become universal. It situates the birth of true self-awareness in a concrete socio-cultural context: the shamanic initiation or “death-and-rebirth” ritual that so many traditions echo in myth.

3 The Snake Cult / Eve Theory of Consciousness: Extending the Model to Myth and Mind#

The Snake Cult of Consciousness, also called the Eve Theory of Consciousness, builds directly upon Froese’s ritual-origins model, enriching it with additional interdisciplinary insights. Proposed by Andrew Cutler, the Eve Theory agrees that altered-state rituals were the engine of humanity’s cognitive revolution, but adds a specific narrative for what those rituals were and who drove the process . In this account, the concept of self – the realization “I am” – was a discovery, likely made by certain individuals (perhaps those with predispositions for introspection) and then diffused memetically through ritual teaching . The theory’s nickname comes from the hypothesis that snake venom was the primordial entheogen (psychedelic substance) used to induce the critical self-awareness state , an idea evocatively summarized as “giving the Stoned Ape theory fangs” . In other words, where others have suggested mushrooms or other plants sparked human consciousness, Cutler’s model points to serpent venom as a potent and readily discovered means to ritualize mind alteration .

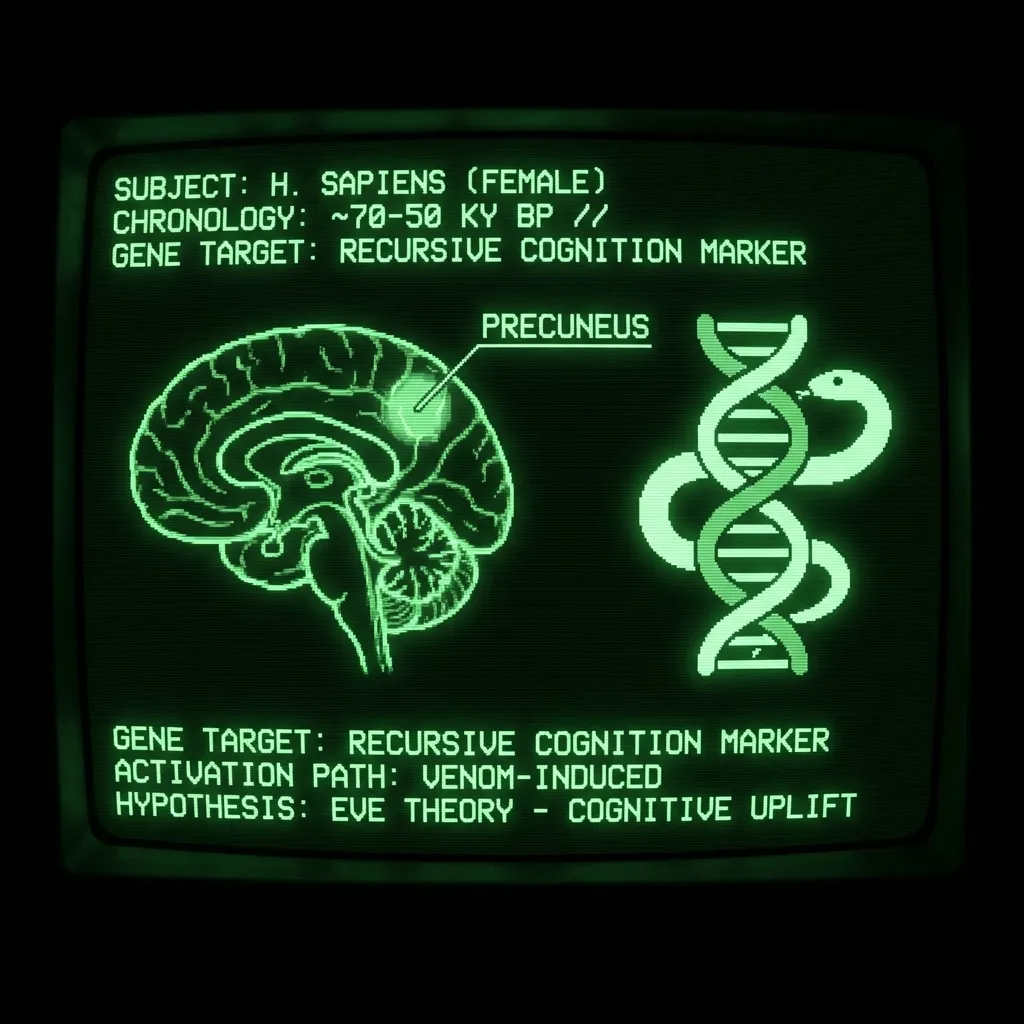

Core tenets of the Eve Theory can be outlined as follows. First, it centers on the role of recursive cognition – the brain’s ability to turn thoughts back on themselves (think about thinking, know that one knows). This capacity for recursion underpins self-awareness, inner speech, autobiographical memory, and volitional planning – essentially the whole suite of mental abilities we recognize as the human condition. In cognitive science terms, recursion enables a meta-representational mind: the mind can represent itself as an object, which is the crux of subject–object separation. Eve Theory concurs with Froese that such reflective consciousness did not gradually evolve over hundreds of thousands of years, but rather emerged in a specific window in the late Pleistocene. The model proposes an initial emergence roughly between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago, with the process continuing into the Holocene (the last ~12,000 years) as self-awareness became fully stabilized. Notably, it argues for a gendered dynamic in this cognitive revolution: women likely attained self-awareness first, with men following later. Several lines of reasoning support this claim. From an evolutionary psychology standpoint, the female niche in prehistoric societies – especially for mothers rearing children – may have favored greater social monitoring, empathy, and modeling of others’ minds. These are precisely the pressures that would exercise and enhance recursive mind-reading abilities (what in modern terms might be called high social or emotional intelligence). Psychometric evidence today indeed shows females outperforming males in measures of social cognition and emotional intelligence, consistent with having an edge in self-referential processing. Neuroscience adds another provocative clue: the precuneus, a key brain region in the default mode network associated with self-awareness and introspection, is one of the most sexually dimorphic regions in the human brain. It is functionally and anatomically more developed in women on average, and is linked to capacities like episodic memory and mental time travel where women also show advantages. Such differences suggest that if any subgroup of humans were to spontaneously achieve a novel recursive cognitive skill, females are strong candidates. The Eve Theory thus envisions that perhaps “Eve” (symbolically speaking, a primordial woman or women) experienced episodic self-awareness first – a flicker of introspective consciousness – and that this phenomenon gradually increased in frequency. Eventually, through social learning or deliberate ritual, these women could teach the experience to others.

This leads to the second pillar of the Eve Theory: self-awareness could be taught (at least partially) by guiding others through the same transformative state. Here is where ritual comes back to the forefront. Just as Froese outlined how shamans or elders might induct youths into dualistic consciousness via ordeals, the Eve Theory provides a concrete content for those rituals. The hypothesis singles out snakebite-induced trance as an early and powerful method to induce the “death-and-rebirth” experience of finding the inner self. The logic of this scenario is compelling when one considers the discovery process: early hunter-gatherers would have known the fright and altered perception that comes with venomous snakebite, an existential threat that often produces intense physiological and psychological effects. At some point, a victim of a snakebite may have endured a surreal near-death state – possibly experiencing dissociation, hallucinations, or seeing one’s life “flash before the eyes” – and yet recovered (perhaps thanks to a fortunate dry bite or a primitive antidote). That person, having survived the serpent’s trial, would carry a profound revelation of “being a mind” apart from the body’s suffering. The Eve Theory suggests that early humans recognized this phenomenon and ritually harnessed it, incorporating controlled snakebite (with precautions like applying herbal antivenom) into initiatory ceremonies. In essence, snakes “found” us, as Froese himself remarked upon hearing this idea – unlike psilocybin mushrooms which require deliberate foraging and ingestion, venom can intrude upon humans, potentially making it the earliest psychedelic teacher. Ethnographic evidence lends surprising support: even in modern times, ophidian intoxication is real. In South Asia today, snake handlers have been reported to intentionally dose themselves with cobra venom to attain trance states, and recent arrests of individuals selling snake venom for recreational use confirm that venom is indeed used as a mind-altering drug. One popular guru in India (Sadhguru) openly speaks of venom’s effects: “Venom has a significant impact on one’s perception… It brings a separation between you and your body… It may separate you for good,” he says, describing his own near-fatal venom experiences as a form of death and rebirth. Such accounts strikingly echo the role posited for venom in the Eve Theory – as a chemical catalyst for out-of-body experiences and the realization of an independent soul or self.

Third, the Eve Theory argues that mythology and symbolic culture preserve the memory of this formative process. In the language of semiotics and religious studies, we might say the theory “unites Darwin with Genesis” by reframing ancient myths as garbled historical narrative. Nearly every culture’s creation myths feature serpents and forbidden knowledge: from the biblical Garden of Eden – where a snake prompts the first humans to attain knowledge of good and evil – to the Native American Great Snake, the Australian Aboriginal Rainbow Serpent, or the Aztec Quetzalcoatl, serpents are mythically linked to wisdom, transformation, and the origins of humanity. The Eve Theory takes these widespread motifs not as mere coincidence but as cultural trace fossils of a real prehistoric “cult of consciousness.” On this reading, the Eden story of Eve, the Serpent, and the Fruit of Knowledge is an allegorical record of how women (Eve) and a serpent (venom ritual) brought forth conscious self-awareness (knowledge of one’s nakedness, i.e. introspective self-recognition). The “fall from Eden” symbolizes the irrevocable loss of our earlier animal-like innocence once the ego was born. Similarly, many cultures have legends of humans originally living as automatons or in a dream, until some trickster or teacher awakens them – narratives that resonate with the Eve Theory’s timeline of a late awakening of inner life. Even the practice of trepanation (drilling holes in the skull), documented in Neolithic skeletons worldwide, might be reinterpreted as desperate attempts to free or cure the mind newly plagued by voices and thoughts (as if “letting the demons out” once selfhood emerged). By casting myth and archaeological oddities in this light, the Eve Theory bridges semiotics and anthropology: mythic symbols (the serpent, the forbidden fruit, the mother goddess, etc.) are seen as signs pointing to real cognitive events and ritual practices in the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene.

Finally, a critical component of the Eve Theory is its attention to biological evolution and genetics as intertwined with the cultural spread of consciousness. In a manner akin to modern gene–culture coevolution models, it posits that once the “self-awareness meme” began to spread via rituals, it created strong selection pressures on our population. Individuals capable of robust recursive thought and ego stability may have had advantages (or at least, those unable to adapt to self-awareness may have been at a disadvantage). Over generations, this could lead to genetic adaptations reinforcing the neural basis of recursion. The theory intriguingly cites the example of the Holocene epoch (within the last ~10,000 years) as a period of intensified selection. During this time, human societies underwent massive upheavals – the agricultural revolution, population booms, and possibly the final universalization of introspective consciousness. Genetic studies have noted a mysterious bottleneck in Y-chromosome lineages around 6,000 years ago, when an estimated ~95% of male lineages died out. While the causes of this “Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck” are debated (social stratification? warfare?), the Eve Theory speculates it might reflect selective sweeps related to the new cognitive regime. In simple terms, as men “woke up” later, those who adapted (or were descended from already conscious women) may have outcompeted others, dramatically pruning male genetic lines. The theory even incorporates the contribution of Neanderthal admixture, noting that archaic genes might have aided the development of recursion in certain lineages. In a broad evolutionary sense, the spread of the self-awareness trait can be seen as a quasi-speciation event – not a true species split, but a memetic and cognitive speciation where a new kind of human mind emerged and proliferated. This is why the theory earns the moniker “How humans evolved a soul” (the subtitle of its v3.0 version) : it treats the soul (the inner self) not as a metaphysical given, but as an evolved feature – one that spread through both cultural transmission and natural selection. By weaving together neuroscience, gender studies, mythology, and population genetics, the Eve Theory substantially extends Froese’s framework. Froese identified the mechanism (ritualized altered states) and the function (inducing reflective consciousness) that solved the puzzle of symbolic cognition. Eve Theory takes this further by proposing a specific scenario that is rich enough to be tested across disciplines: it identifies the likely agents (women), substances (venom), and cultural signatures (serpent myths, initiation cults) involved in humanity’s conscious awakening.

4 Comparative Analysis - Eve Framework vs. Alternative Models#

Both Froese’s ritualized mind hypothesis and the Snake Cult/Eve Theory stand in contrast to more conventional explanations for the origins of human consciousness. It is instructive to compare these frameworks with leading alternatives from cognitive science, anthropology, and evolutionary theory. The central question is: How well does each model account for the empirical record and the explanatory challenges (like the Sapient Paradox)? We argue that the Eve Theory, as an extension of Froese’s model, offers the most comprehensive and interdisciplinary robust account – effectively fulfilling Froese’s goals and surpassing rival theories.

Gradualist and Continuity Models: A long-standing view in paleoanthropology is that there was no singular “awakening” – rather, human cognitive capacities accumulated gradually as our brains grew and our societies became more complex. In this view, symbolic thought might have begun to flicker with early Homo sapiens (or even earlier hominins like Homo erectus or Neanderthals), slowly developing over hundreds of thousands of years, with art and religion eventually coalescing when a tipping point in population size or communication was reached. While plausible in principle, such models struggle to explain the pronounced temporal gap and the binary-like shift in the archaeological record. The near-absence of clear symbolic artifacts prior to ~50k years ago, followed by an explosion of cultural innovation, hints at a non-linearity that pure gradualism doesn’t capture. Moreover, continuity theories offer little insight into how the subjective phenomenology of consciousness (the feeling of “I”-ness) might have arisen. They often conflate having a big brain or language with automatically having introspective self-awareness. Froese’s hypothesis specifically targets this weak point: even a brain with the computational capacity for recursion might not activate full self-modeling without some experiential trigger. By positing intentional rituals as an “external catalyst,” Froese introduces a needed discontinuity – a cultural stimulus that precipitated a cognitive phase change. The Eve Theory strengthens this by pointing to real-world practices (e.g. shamanic trance induced by venom) that could have provided exactly such stimuli. Thus, compared to continuity models, the Froese–Eve framework better accounts for the suddenness of the Upper Paleolithic cognitive revolution and explains why fully modern consciousness might have appeared late and unevenly (first in some groups, then spreading), rather than uniformly emerging as soon as the brain was anatomically ready.

Spontaneous Mutation or Brain Circuit Change Models: Another influential hypothesis is that a genetic mutation or neurobiological reorganization gave rise to modern human cognition. Noam Chomsky and colleagues, for instance, famously speculated that a single mutation yielded the capacity for recursion (perhaps by altering neural wiring), which in turn enabled language and abstract thought. In this view, one lucky human (sometimes jokingly called “mutant genius”) was born with a brain capable of syntax and introspection, and this trait spread. While this idea highlights the importance of recursion (in agreement with Eve Theory on that point), it faces similar issues pinning down timing and mechanism. If such a mutation occurred ~100k years ago in Africa (as Chomsky assumed to align with out-of-Africa migrations), why did the creative explosion happen tens of millennia later? One could argue the trait needed to diffuse genetically through the population, but genetic diffusion (especially if beneficial) should still manifest much sooner than 50,000 years. The Eve Theory offers an elegant twist: perhaps the “mutation” was not a gene at all, but a meme – an idea or practice. In other words, culture, not just DNA, mutated. The “self-awareness meme” (the ritual method to induce an introspective state) could arise in one group and then spread culturally much faster than a gene, yet still produce a time lag while it disseminated and was stabilized biologically. Additionally, recent genomics do suggest our brains are still evolving in the last 50k years (with alleles affecting neural development sweeping through populations), so a hybrid scenario of meme-triggered gene selection fits well. Froese’s model is compatible with genetic contributors – it simply places the emphasis on practice-driven development instead of a miraculous mutation. Compared to a purely genetic account, the ritual hypothesis better integrates the symbolic content: a gene might wire a brain, but a ritual teaches a mind. By including the instructional, demonstrative aspect (“show, don’t tell” initiation), it explains not just that humans became self-aware, but how they realized they were and how they conveyed that realization socially.

Psychoactive Catalyst Theories (Stoned Ape Hypothesis): A popular speculative idea, championed by Terence McKenna, is that ingestion of psychoactive plants (like psilocybin mushrooms) by early humans led to breakthroughs in cognition – increased creativity, proto-religious insight, even protolanguage in McKenna’s view. This so-called “Stoned Ape” hypothesis shares an intuitive similarity with Froese’s: both credit psychedelics or altered states with boosting cognition. However, McKenna’s theory lacked a clear mechanism for how these drug experiences would become entrenched or taught across generations. It also did not specifically address the emergence of the self-model or subject-object differentiation; it was more focused on general intelligence and imagination. The Snake Cult/Eve Theory can be seen as a more scientifically grounded successor to the stoned ape notion. By identifying structured rituals and social transmission, Eve Theory avoids the pitfall of being a just-so story about drug use. It recognizes that random intoxication alone wouldn’t change a species, but ritualized, repeated use embedded in cultural contexts could have lasting effects. Moreover, the choice of snake venom over mushrooms addresses a practical challenge: availability and discovery. Psychedelic mushrooms might not have been accessible to all groups year-round, and recognizing their mind-altering properties requires experimentation. By contrast, snakes were ubiquitous threats; a near-death venom experience could force itself upon humans without deliberate seeking. As Froese noted, a major critique for any “altered mind” theory is explaining how the practice started – the discovery problem. Snake venom neatly “solves the discovery critique” because humans didn’t need to discover it – it discovered humans (in the form of bites). Once a connection was made that certain controlled doses or preparations of venom induce a profound trance (one that coincidentally aligns with what shamans were achieving via other means), it could be adopted as a ritual tool. Thus, the Eve Theory doesn’t dismiss McKenna’s insight that chemistry mattered; it refines it into a testable anthropological claim (e.g. one could look for ancient snake cult artifacts, or biochemical evidence on ritual objects). It’s telling that the serpent motif is far more universal in ancient art and myth than any mushroom or plant iconography, hinting that if a psychoactive agent was sacralized in early religion, snake venom is a prime candidate. In terms of explanatory scope, Eve Theory goes beyond McKenna by embedding the pharmacological catalyst within a broader cognitive-developmental and cultural diffusion framework – something the stoned ape idea lacked.

Late-Brain Maturation Theories (Bicameral Mind): In psychology and philosophy, Julian Jaynes’s famous (if controversial) bicameral mind theory proposed that human self-consciousness is a recent development – arising only in the last 3,000 years as society became complex, replacing an earlier state in which people experienced their thoughts as “voices of gods.” While mainstream science places consciousness much earlier, Jaynes’s work did highlight an important notion: that what we consider normal subjective awareness might not have existed in ancient minds, and that cultural changes (like language or metaphor) could trigger mental restructuring. The Eve Theory can be seen as a more empirically grounded cousin of Jaynes’s idea. It retains the central theme that consciousness is a culturally driven, learned phenomenon rather than a timeless trait, but aligns the timeline with the Upper Paleolithic and Neolithic evidence (tens of thousands of years ago, not mere thousands). Moreover, Eve Theory ties the emergence of inner voice to the evolution of recursion and language, which almost certainly was complete by the Paleolithic, unlike Jaynes’s Bronze Age timing. In effect, Eve Theory rescues the spirit of the bicameral hypothesis (that there was a real transition in the mode of consciousness) while discarding its problematic chronology. It also suggests a far more concrete catalyst (ritual practices and possibly neurotoxic trance) rather than Jaynes’s nebulous suggestion of historical calamities. By doing so, it can engage with tangible data – for example, tracking pronoun use or self-referential art in ancient texts and artifacts. Froese’s model and Jaynes’s share a philosophical commonality in treating consciousness as emerging from socially structured experiences rather than purely biological evolution; the Eve Theory cements that link with scientific plausibility. It “drops” the awakening of self back into the prehistoric context where it can be correlated with things like cave paintings, complex burials, and the first cities (e.g., Göbekli Tepe ~11,000 years ago, often seen as an early temple that might reflect new forms of thought). Thus, compared to Jaynes’s late-breakdown scenario, the Froese–Eve narrative is both more chronologically appropriate and more richly supported by cross-disciplinary evidence.

Shamanic Initiation and Religious Behavior Models: Anthropologists and cognitive archaeologists such as David Lewis-Williams, Steven Mithen, and others have long argued that religious ritual and symbolism were central to making us human. Mithen, for instance, points to a cognitive fluidity emerging in the Upper Paleolithic, and Lewis-Williams connects the dots between altered states, cave art, and the birth of religion. Froese’s work explicitly builds on this tradition by providing a mechanistic cognitive account (the interruptions of normal consciousness forging a reflective self). The Snake Cult of Consciousness can be viewed as an extension that identifies the prototypical “mystery cult” at the dawn of human self-awareness. Indeed, Cutler’s research highlights archaeological signs of a Paleolithic mystery cult: for example, archaeologists have noted sites like Tsodilo Hills in Botswana, where a 70,000-year-old rock resembling a python appears to have been a focus of ritual activity (potentially one of the oldest snake-related rituals on record). The diffusion of a death-and-rebirth ceremony centered on a serpent could explain why even far-flung cultures (with no contact in Holocene times) share mythic motifs – a phenomenon that purely local development theories of religion can’t easily handle. By positing an early, widespread cult practice, Eve Theory accounts for both the universality and the antiquity of serpentine symbolism. It thus complements religious studies perspectives that see common archetypes across myths. Semiotically, the serpent in Eve Theory is the signifier of the conscious self’s birth – a sign that became enshrined in collective memory. No alternative model so neatly ties together the threads of ritual practice, cognitive change, and mythological record. Froese gave a general explanation for why initiation rituals would matter; Eve Theory provides a story of which rituals, and how those stories persisted. Moreover, Eve Theory’s inclusion of demographic and genetic consequences (like selection for recursion, or new mental illnesses like schizophrenia appearing) gives it empirical hooks that religious-studies-only narratives lack. It predicts, for instance, that we might find an increase in genetic markers of neurological resilience or changes in brain-related gene frequency in the late Pleistocene/Holocene – a prediction testable with ancient DNA. Competing views that religion emerged as a byproduct or purely for social cohesion don’t venture such testable claims about cognitive genetics. In this sense, Eve Theory is empirically fertile: it not only unifies disparate data (myths, cave art, brain differences, genetic bottlenecks), but also generates hypotheses for future research in paleogenomics, archaeology, and psychology.

In summary, the Snake Cult of Consciousness or Eve Theory acts as the synthesis of many prior ideas while overcoming their individual limitations. It agrees with the psychedelic theories that mind-altering substances were pivotal, but identifies a realistic candidate (snake venom) and integrates it with ritual structure and accident discovery. It agrees with cognitive genetic theories that a change in recursion ability was key, but shifts the cause from a mystery mutation to a cultural innovation that subsequently influenced genes. It resonates with anthropological theories that women played crucial roles in societal innovations (e.g. early agriculture, as some have argued), extending that to the realm of mind – a convergence of feminist anthropology and cognitive science that few other models consider. And it validates Froese’s insight that structured experiences can drive cognitive evolution, giving his hypothesis the rich narrative and worldwide scope needed to truly explain why humans everywhere share this peculiar reflective consciousness. In doing so, Eve Theory arguably fulfills Froese’s explanatory goals more completely than Froese’s own initial formulation: it not only explains how subject-object dualism could arise (via ritual), but also why particular symbols (snakes, trees of knowledge) are so salient, and what consequences this shift had for our species’ biological and cultural trajectory. No alternative theory provides such a holistic, interdisciplinary picture of the origin of human consciousness.

5 Interdisciplinary Reflections - Speaking in Many Tongues#

One of the strengths of the Froese–Eve framework is that it can be described in the languages of many different disciplines, making the same fundamental insights accessible across domains. To a cognitive scientist, this theory is about the emergence of recursive self-modeling and the expansion of the brain’s default mode network activity through deliberate perturbation of normal sensorimotor coupling . It suggests that the human brain achieved a new level of metacognitive integration as a result of ritual practices – effectively an example of neural plasticity harnessed by culture. Key terms here include metacognition, working memory enhancement through trance, and possibly the training of inner speech circuits as initiates learned to reflect on their own thoughts. To an anthropologist, the very same process can be framed as a rite of passage that enabled symbolic culture: early shamans developed liminal rituals (in Turner’s sense of communitas and liminality) that created a psychological threshold crossing, after which initiates could participate in the tribe’s symbolic systems (art, language, myth) with a fundamentally transformed understanding . Terms like initiation, shamanism, mythic charter, cultural transmission would be emphasized. An evolutionary biologist might describe the theory as a case of gene–culture coevolution and a rare instance of a cultural “invention” driving a biological adaptation in the human lineage. Here the language might invoke selection pressure for enhanced neural recursive loops, population bottleneck, and fitness advantage of introspective insight, highlighting how a behavioral practice became an inherited capacity over time . A semiotician or linguist could interpret the emergence of subject-object dualism as the birth of true symbolic reference: only once humans conceived of the self as an object could they fully grasp that a sign or word can stand for an object distinct from oneself. This aligns with Terrence Deacon’s thesis of the co-evolution of language and brain – in semiotic terms, the ritual separation of self and body enabled the triadic relationship between sign, object, and interpretant (the self who understands the sign). In this jargon, the theory describes a move from indexical consciousness (embedded in the here-and-now) to symbolic consciousness (able to detach and abstract), catalyzed by a cultural semiotic intervention. A scholar of religious studies or mythology might rephrase the narrative as the first esoteric knowledge (gnosis) being discovered and propagated: the “knowledge of the self” as a kind of secret or sacred revelation initially limited to a cult and later diffused. They might compare it to later historical mystery religions (the Eleusinian mysteries, shamanic initiation rites, etc.) and use terms like mystical death, rebirth, ascension of consciousness, dualism of soul and body – noting that the Eve Theory provides a likely Ur-myth behind all these later spiritual echoes . Lastly, a psychometrician or psychologist might discuss how this proposed scenario implies changes in measurable traits – for instance, increases in general intelligence (g) or the emergence of new dimensions of personality once self-reflection kicked in. The theory’s emphasis on sex differences can be tied to present-day data: females’ higher average empathic accuracy and social cognition scores , or the greater female connectivity between brain hemispheres , might be the lingering shadow of women’s pioneering role in conscious thought. They might even point out that certain pathologies (like schizophrenia, which often involves hallucinated voices and a breakdown of the self’s unity) are uniquely human and would have been impossible before true selfhood evolved . This casts mental illness research in an evolutionary light: e.g., the “cost” of evolving internal dialogue is that occasionally the dialogues run amok.

This exercise in translation across disciplines is not mere wordplay – it underscores that the Snake Cult/Eve Theory is robust enough to engage diverse methodologies. Its claims can be evaluated by neuroscientific imaging (do altered states facilitate the decoupling and increased brain integration as predicted?), by archaeological digs (do we find early ritual centers with snake iconography or evidence of ritual bone alterations in adolescents suggestive of initiations?), by genetic analysis (are there alleles dating to the Holocene that correlate with neural plasticity or cognitive function?), and by comparative mythology or linguistics (do languages and myths encode a memory of a time “before I” versus “after I”?). In each domain, the core idea is reframed but remains coherent: human consciousness emerged through a confluence of biology and culture, triggered by ritual practices that taught us to become aware of awareness itself. By articulating the theory redundantly in different scholarly languages, we make its insights accessible to an interdisciplinary audience – from AI systems modeling cognitive architectures (which might analogize the process to a training regime that causes a neural net to develop a self-monitoring module) to philosophers of mind examining the first-person perspective and its origin.

6 Conclusion#

Dr. Tom Froese’s ritualized mind hypothesis and the Snake Cult of Consciousness (Eve Theory) together present a powerful, unifying narrative for one of humanity’s greatest mysteries: how did we become aware of ourselves? Froese addressed the foundational problem of cognitive evolution by identifying a plausible cultural solution to the emergence of symbolic, reflective consciousness – something that neither standard evolutionary gradualism nor abrupt mutation theories could satisfactorily explain. By recognizing ritual and social practice as a driving force in cognitive development, he bridged a gap between evolutionary biology and cultural anthropology, showing that the software of the mind could be upgraded by the “training data” of ritual long before the hardware (brain anatomy) was fully modern. The Eve Theory of Consciousness builds on this cornerstone and extends it into a comprehensive model that is arguably the most developed extension of Froese’s core insight. It fulfills the explanatory goals Froese set – explaining subject-object separation, the rise of symbolism, and the resolution of the Sapient Paradox – and does so in a way that integrates evidence and terminology from many domains. In the Eve Theory, we see an account that not only asks when and how we became conscious, but also who, why, and with what consequences. It paints the transition to consciousness as a real historical event – a cognitive revolution – that left echoes in our genes, our stories, and our brains.

No single theory about the origin of mind can be definitively proven, and the Snake Cult of Consciousness remains a bold hypothesis. Yet its merit lies in its explanatory power and interdisciplinarity. It takes Froese’s scientifically grounded model of ritual-driven cognitive evolution and infuses it with mythological, archaeological, and even biomedical detail – yielding a scenario that is at once imaginative and deeply empirical. It provides a narrative scaffolding upon which future research can build: for example, testing for neurotoxic residues in ancient initiation sites, analyzing ancient DNA for selection signals on cognitive function genes, or re-examining creation myths through the lens of collective memory. In science, a strong theory often reveals itself by its ability to make sense of anomalies and to unite phenomena previously seen as unrelated. The Eve Theory does just that – connecting the dots from African rock art to Genesis, from puberty rites to brain default networks, from snake handlers to serotonin receptors. As a natural extension of Froese’s insight, it does not undermine the ritualized mind hypothesis but rather amplifies it, suggesting that Froese indeed solved a crucial piece of the puzzle of human cognitive evolution, and that by following the snake’s trail through our deep cultural memory, we may find the fullest story of how the human soul – the aware self – was born.

In conclusion, when evaluated alongside alternatives, the Froese–Eve framework stands out as a compelling synthesis: it posits that consciousness was not merely an accident of biology nor an inevitability of big brains, but a precious discovery – one initially made perhaps by a few and then propagated intentionally, even ritualistically, until it became second nature (and eventually, genetic nature). This view elevates the role of our ancestors not just as passive recipients of evolution’s gifts, but as active participants in directing their own cognitive fate. It suggests that the “cult of consciousness” was humanity’s first and greatest invention – an invention that turned Homo sapiens into the narrators of their own story. Such a perspective is profoundly interdisciplinary, unabashedly ambitious, and for the first time, gives a theory of consciousness’s origin that is as rich and strange as consciousness itself.

FAQ #

Q1. What is the Sapient Paradox?

A. It’s the puzzle of why behaviourally modern traits — art, symbolism, complex ritual — explode tens of millennia after anatomically modern humans evolve (~200 kya).

Q2. How does Froese’s Ritualised-Mind Hypothesis solve it?

A. Initiation rites that induce altered states catalyse subject–object separation, bootstrapping symbolic culture in each generation.

Q3. How does the Eve / Snake-Cult Theory extend Froese’s idea?

A. It highlights female-led snake-venom rites, accounting for universal serpent myths and tying the diffusion of self-awareness to gene–culture coevolution.

Q4. Is this framework compatible with “Stoned Ape” or single-mutation theories?

A. Yep. It retains altered-state chemistry (venom > mushrooms) while seeing genes as followers of culturally triggered selection rather than a lone miracle mutation.

Q5. What testable predictions does the model make?

A. Late-Pleistocene sweeps on neural-plasticity genes, venom residues on ritual artefacts, and sex-dimorphic DMN patterns mapping recursion’s spread.

Sources#

- Froese, Tom. The ritualised mind alteration hypothesis of the origins and evolution of the symbolic human mind. Rock Art Research (2015). [Summarized in Cutler 2024]

- Cutler, Andrew. “The Origins of Human Consciousness with Dr. Tom Froese.” Vectors of Mind (Nov 13, 2024) – Podcast transcript highlighting Froese’s model.

- Cutler, Andrew. “The Snake Cult of Consciousness.” Vectors of Mind (Jan 16, 2023) – Original essay proposing the Eve Theory (“Giving the Stoned Ape Theory fangs”).

- Cutler, Andrew. “Eve Theory of Consciousness (v2).” Vectors of Mind (2023) – Updated version emphasizing gender and interdisciplinary evidence.

- Cutler, Andrew. “Eve Theory of Consciousness v3.0: How humans evolved a soul.” Vectors of Mind (Feb 27, 2024) – Comprehensive essay on the Eve Theory.

- Cutler, Andrew. “The Snake Cult of Consciousness – Two Years Later.” Vectors of Mind (Aug 2025) – Follow-up analysis corroborating the theory with new evidence (snake venom use, genetics, etc.).

- Sadhguru (Y. Vasudev). The Unknown Secret of how Venom works on your body – YouTube discourse on effects of venom.

- Selected references on human cognitive evolution and myth: Witzel (2012) on pan-human creation myths; Wynn (2016) on late emergence of abstract thought; Lewis-Williams & Dowson (1988) on entoptic imagery in cave art; Chomsky (2010) on recursion mutation; McKenna (1992) on “stoned ape” hypothesis; Jaynes (1976) on bicameral mind.