TL;DR

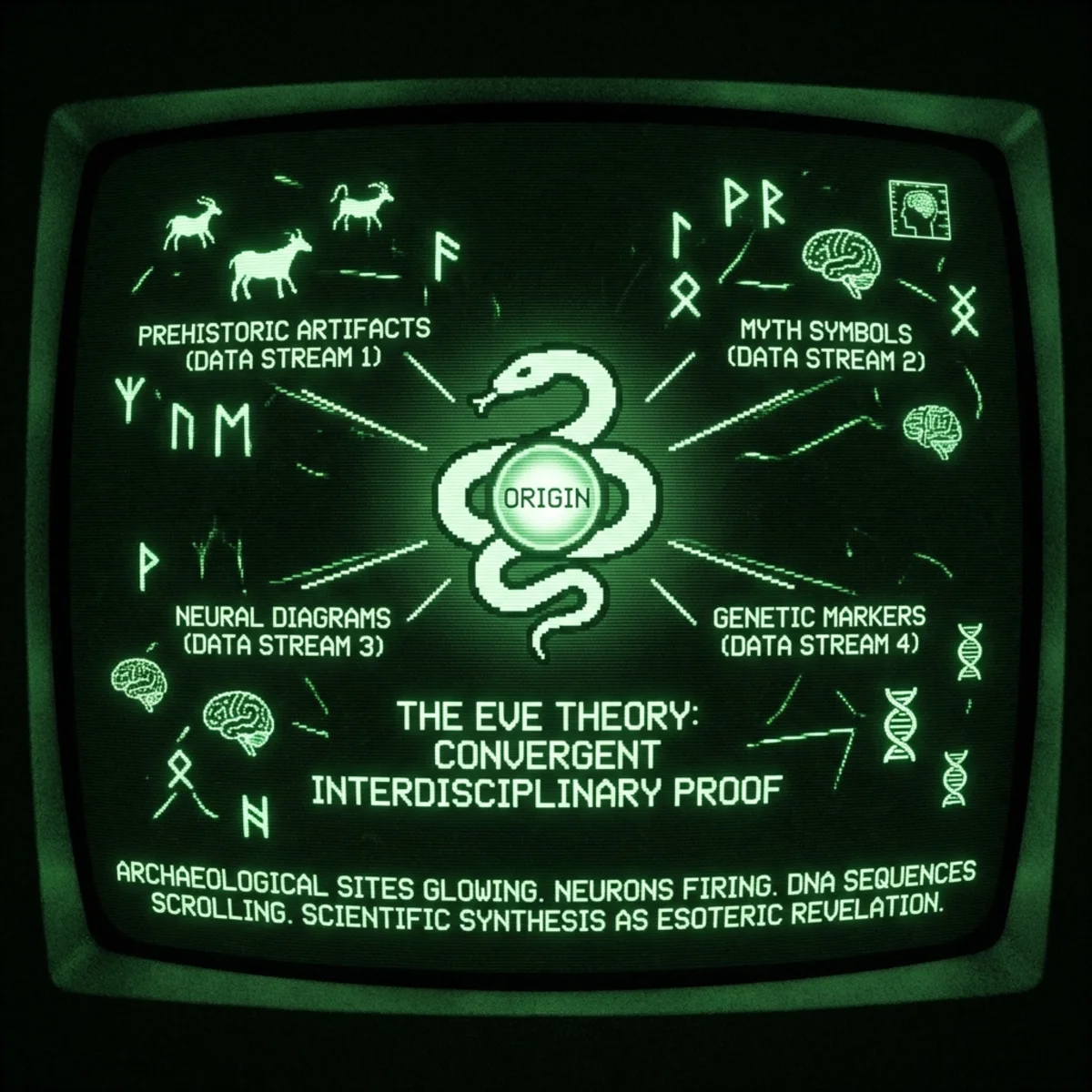

- A major paradox in human evolution is why behaviorally modern traits (art, symbolism, language) appeared tens of millennia after Homo sapiens became anatomically modern 1 2. The Eve Theory addresses this by positing a late prehistoric “phase change” to true self-awareness, catalyzed culturally rather than by a sudden mutation.

- Cognitive scientists have proposed that ritualized altered states – intense initiation ceremonies inducing out-of-body experiences – could trigger the reflective, dualistic consciousness that defines humanity 3 4. New evidence from archaeology and neuroscience supports this: early art and burials bear traces of trance rituals, and brain-network studies show how such ordeals can spark a self-observing “observer mind.”

- The Eve Theory specifically suggests women were the first to achieve self-awareness and spread it through ritual. Notably, females show small but consistent cognitive advantages in social empathy and episodic memory 5 6 – faculties tied to introspection and “mental time travel.” Even the brain’s default-mode network (linked to the self) is more developed in women on average 7. In deep prehistory, women’s roles (e.g. maternal social monitoring) may have primed them to pioneer the “I am” insight.

- In this hypothesis, the primordial initiation involved venomous snakes as natural entheogens. Anthropological reports and historical sources reveal that snake venom has been used to induce trance: e.g. classical Greek mystery cults possibly applied diluted viper venom to enter ecstatic states 8 9. Modern cases from India document people intentionally getting cobra bites or “milking” snakes to experience hallucinogenic effects 10 11. Snake venom contains potent neuroactive compounds (including nerve growth factors) that can radically alter perception and cognition 11 12.

- Cross-cultural mythology and archaeology offer striking corroborations. Mythic traditions worldwide depict a serpent granting knowledge or soul to humankind – from Eden’s snake and the forbidden Tree of Knowledge to the Australian Aboriginal Rainbow Serpent and the Aztec Quetzalcóatl 13 14. Such lore may encode a real prehistoric “serpent cult.” Archaeologically, even the earliest known shamans were often women and associated with animal symbolism: a 12,000-year-old burial in Israel of a disabled female shaman was laden with animal parts and likely honored for spiritual prowess 15 16. Together, these clues reinforce the Eve Theory’s vision of human consciousness awakening through a female-led, snake-centric rite – a convergence of biology, culture, and myth.

“Then the eyes of both of them were opened, and they realized they were naked.” – Genesis 3:7, on the Serpent’s gift of self-knowledge

Rethinking the “Sapient Paradox”#

For decades anthropologists have puzzled over the Sapient Paradox – the disconnect between our species’ early anatomical origin and the much later flowering of modern behavior 1. Fossils show that Homo sapiens with brains like ours existed ~200,000 years ago, yet the archaeological record stayed remarkably static for over 100 millennia. Only around 50,000–40,000 years ago (the Upper Paleolithic) do we see an explosion of symbolic artifacts: cave paintings, intricate tools, personal ornaments, musical instruments, and evidence of religious ritual 17 18. This abrupt shift – sometimes termed the “Cognitive Revolution” – has inspired competing explanations. Was it a genetic mutation that suddenly rewired our brains for language and abstract thought 19? Or was it a slow cumulative process in Africa, now obscured by sparse evidence 17 20? Either way, something extraordinary happened to make our ancestors “fully human.”

One intriguing approach reframes the problem: perhaps anatomically modern brains required a cultural trigger to unlock their potential. Cognitive scientist Tom Froese argues that early humans lacked a clear subject–object distinction – they lived in an immersive stream of experience without reflecting on themselves 21 22. To become self-aware, they first needed to be shaken out of this default state. Froese’s Ritualized Mind Hypothesis posits that deliberate altered-state rituals – intense rites of passage involving sensory deprivation, pain, isolation, or psychoactive substances – provided the necessary jolt 3 23. These ceremonies, analogous to shamanic initiations observed in historic cultures, would induce out-of-body or near-death experiences that teach an initiate the sense of a separable self 24 25. In effect, culture bootstrapped cognition: organized rites served as “training wheels” for the brain to adopt a recursive, reflective mode of thought 26 27. Over generations, natural selection could then favor individuals better able to handle and perpetuate this new mindset 28 29. This theory aligns with archaeological evidence that the first art and religious icons often emerge alongside signs of ritual practice. Notably, some of the very earliest art – prehistoric cave paintings with geometric patterns and therianthropic (human-animal hybrid) figures – strongly evoke trance visions and shamanic themes 30. Researchers have long suspected that Upper Paleolithic paintings of entoptic motifs (dots, zigzags, spirals) reflect the hallucinations of people in altered states 30. In short, ritual may have been the midwife of consciousness, resolving the Sapient Paradox by providing the missing catalyst that a big brain alone could not ignite 26 27.

Women at the Vanguard of “I Am”#

The Eve Theory builds on this framework and makes it more specific: it was likely women who first achieved stable self-awareness and then spread it culturally 31 32. This proposal may sound provocative, but several lines of evidence lend it plausibility.

First, consider the demands on social cognition in prehistoric female roles. Mothers and gatherers, for instance, needed keen awareness of others’ needs and intentions – from soothing infants to coordinating in camps. This lifestyle would strongly exercise theory of mind (attributing mental states to others) and episodic memory (remembering who did what, when), mental faculties closely tied to introspective capacity 33 7. Modern psychometric research indeed finds that women, on average, outperform men on many tasks of social and emotional cognition. A large cross-cultural study of 300,000+ participants found a consistent female advantage in reading others’ feelings and thoughts (the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test of theory of mind) across 57 countries 6 34. Likewise, a comprehensive meta-analysis of 1.2 million people concluded that women have a slight but significant edge in episodic memory – especially for verbal events, faces, and sensory details – whereas men excel more at spatial memory 35 36. Episodic memory is essentially the ability to mentally time-travel through one’s own past experiences, a cornerstone of a self-concept. The fact that women generally recall personal events more vividly and accurately than men 37 36 suggests greater facility with the autobiographical, self-referential thinking that underlies an “inner narrative.”

Neuroscience provides intriguing correlates: brain imaging studies show that women tend to have a proportionally larger and more active precuneus – a key hub of the default mode network associated with self-reflection and identity 7. This brain region is implicated in assembling the autobiographical self and is one of the most sexually dimorphic cortical areas 7. While the science is still evolving, such findings hint that females may, on average, engage the neural circuitry of introspection more readily. It is important to avoid essentialist or determinist claims here: individual variation swamps sex differences, and cultural factors shape minds enormously 38. Yet from an evolutionary perspective, if any subgroup of humans around 100,000–50,000 years ago was more predisposed to stumble upon a new recursive cognitive trick, women are credible contenders 39 40.

Anthropology also offers suggestive clues. In many traditional societies, women have been the innovators of symbolic culture – for example, early pottery and textiles are often attributed to female artisans, and some have argued women played outsized roles in the origin of agriculture. It stands to reason that psychological innovations could be similar. Notably, the earliest known shamans in the archaeological record include females: a famous case is the grave of a roughly 45-year-old woman from 12,000 years ago in Hilazon Tachtit, Israel, buried with an elaborate array of animal remains (tortoise shells, a human foot, eagle wing, leopard pelvis) suggesting a ritual specialist or “shaman” figure 15 41. She was physically disabled (with a deformed pelvis and limping gait) yet honored with a feast and unique grave goods, implying revered spiritual status 15 42. Archaeologists Grosman and Munro argue this is the earliest clear shaman burial, and tellingly, it is a woman 15. While one burial can’t decide the issue, it underlines that women were active ritual leaders in prehistory – so the notion of women guiding others through consciousness-altering rites has precedent.

In the Eve Theory scenario, once a few pioneering “Eves” had those first flickers of self-aware consciousness, they shared the revelation. We can imagine these women leading group rituals to induce similar experiences in others – literally teaching the concept of the self by triggering it in their peers. This brings us to the distinctive mechanism the theory proposes: a ritual involving snake venom as the catalyst for transcendence.

Serpent Venom: Nature’s Psychedelic Teacher#

Why snake venom? The hypothesis may sound fantastical, but surprising evidence suggests that ophidian entheogens (snake venoms used to induce mystical experiences) were known in both prehistory and ancient civilizations 10 8. The Eve Theory proposes that early humans discovered self-consciousness through surviving venomous snakebites and then ritualized controlled envenomation as a means to safely replicate the ego-splitting experience 43 44. Unlike rare psychoactive plants or mushrooms, venomous snakes would have been a ubiquitous and formidable part of the environment for African and Eurasian hunter-gatherers. Critically, a snakebite is an abrupt, life-threatening event that can produce intense physiological and psychological effects: pain, paralysis, hallucinations, dissociation, and brushings with death. If a person was bitten and lived (perhaps via a dry bite or herbal antidote), the ordeal could leave a lasting imprint – a sense of having “left one’s body” or seen beyond the veil of normal perception 43 44. Ethnographic observations support this: some cultures viewed surviving snakebite as a spiritual trial that conferred special insight or powers. For instance, reports from the Sioux of the North American plains held that if a youth was bitten during the annual Sun Dance and survived, he might become a sacred healer or visionary (the bite was seen as a sign from the spirit world) 45 46. Across Australia and the Americas, indigenous shamans have traditionally “handled” venomous snakes in ceremonies – often at great personal risk – as a way to prove their communion with spiritual forces or to induce trance states.

Remarkably, direct use of snake venom as a drug is documented in modern times. In India, cases have been reported of people paying snake charmers to administer cobra venom intravenously or sublingually to get high 10 47. A 2018 medical review noted scattered reports of snake or scorpion venom abuse as a substitute for opiates or alcohol – users described dream-like hallucinations and “near-death” euphoria from envenomation 10 47. In one case, a man with long-term opioid addiction was able to quit drugs entirely after a single cobra bite trip, claiming the venom experience “changed” him on a deep level 10 48. These are isolated incidents, but they demonstrate the potent psychoactive impact of venoms on the human mind.

Chemically, many snake venoms are complex cocktails of neurotoxins and proteins that don’t just kill prey – they also affect the nervous system in ways that can alter consciousness. Notably, venom from certain snakes contains extraordinarily high levels of Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) and related neurotrophins 11 12. NGF is a molecule that promotes neuron growth and plasticity. Psychedelic drugs like LSD or psilocybin are known to transiently boost neurotrophic factors and brain plasticity, which researchers believe underlies their ability to “shake the snow globe” of entrenched neural networks (a hypothesis for why psychedelics can help break addictions or depression by forging new neural connections) 49 50. Incredibly, snake venom might be an even more direct neuron-growth stimulator: studies in the 1950s discovered that using snake venom as a reagent yielded NGF extracts thousands of times more potent than other sources 11 51. Recent research suggests components of cobra venom can induce robust neurite outgrowth (growth of neural connections) and are being investigated for treating neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s 12 52. While ancient people knew nothing of NGF, they certainly recognized that venom, in small enough doses, profoundly changes one’s mental state. A famous Indian mystic, Sadhguru, has openly discussed his own experiments drinking diluted snake venom to seek enlightenment. He attests that venom “has a significant impact on one’s perception…It brings a separation between you and your body,” though he warns “it may separate you for good” if one isn’t careful 53 54. Sadhguru’s description – a sense of the self detaching from the body’s sensations – uncannily echoes what Eve Theory posits happened the first time a human thought “I”.

Crucially, there is compelling evidence that snakes and their venoms featured in ancient rites at the dawn of civilization. Classical scholars and ethnobotanists have uncovered tantalizing hints of serpent venom use in the secret rituals of the Mediterranean. The Eleusinian Mysteries of ancient Greece, a yearly initiation ceremony that revolved around death-and-rebirth symbolism, are known to have employed a psychoactive sacrament (the kykeon drink, likely ergot or another hallucinogen). Some historians now argue that venom was also used. Classicist Carl Ruck documents that Greek temple healers “milked” vipers to collect venom, which was mixed into potions or ointments in sub-lethal doses to induce ekstasis (ecstasy or trance) 8 55. He interprets the legend of the Hydra – a serpentine monster with regenerating heads, slain by Heracles using venom-tipped arrows – as coded lore about the therapeutic and visionary uses of snake toxins 8 55. The high priestess at the Oracle of Delphi was called the Pythoness, and while later accounts attribute her trances to gaseous fumes, other sources hint she may have ingested small doses of venom or antidote. Classicist Drake Stutesman notes that ancient observers believed Pythoness priestesses “lapped up snake venom to induce trances at Delphi,” and even some modern scientists bitten by snakes have described vivid hallucinations and “enormous capabilities” during their intoxication 56 57. In Vedic India, the sacred drink Soma (whose identity is still debated) is associated in myth with both snakes and a mix of milk – intriguingly, some Vedic hymns speak of a divine reptile granting a potion of immortality, paralleling the Eve Theory motif of mixing venom and milk as an enlightenment brew 58 59. The recurring theme is that serpents were seen as guardians of special knowledge or life-force, and sometimes that knowledge was literally embodied in their venom.

From a practical standpoint, delivering venom in a controlled way would have been challenging but not impossible for our resourceful ancestors. Some cultures did develop methods: one Greek writer alleged that temple priests administered venom via suppositories to bypass the lethal gut and liver reactions 60. More commonly, venom could be diluted in fats or dairy (mixing venom in milk is a trope in Indian lore and a known folk antidote practice 61 62) and absorbed through mucous membranes. Recent pharmacological studies confirm that even without injection, the tongue is an effective route to rapidly absorb certain neurotoxins into the bloodstream 9. Thus, a Paleolithic ritual might have involved an initiate licking a blade or fang coated with venom, or perhaps receiving a snakebite after ingesting some herbal antivenom as a precaution 43 44. Archaeologically, we can’t directly find venom residues from 50,000 years ago, but we can look for indirect signs: images of snakes in prehistoric art, or unusual patterns of skeletal trauma consistent with snakebite. One fascinating (if controversial) clue comes from Tsodilo Hills, Botswana, where a rock formation resembling a giant python in a cave shows evidence of human activity dating to ~70,000 years ago. One team claimed this was the site of the world’s oldest ritual, a python-worship ceremony, noting artificial indentations in the rock (perhaps to imitate scales) and nearby pigments and spearpoints left as offerings 63 64. Although others have debated this interpretation 65, the idea of a snake cult in the Paleolithic is not far-fetched – snakes are riveting, dangerous creatures that would have inspired awe. If early shamans were searching for ways to induce extraordinary mental states, a deadly snake in a dark cave could be both a literal and symbolic gateway.

Genes, Myths, and the Legacy of a Consciousness Cult#

If a wave of consciousness swept through Homo sapiens in the late Pleistocene – fueled by culture and perhaps involving chemical trance – we might expect to see its echoes not just in myth but even in our genomes. The Eve Theory indeed predicts a form of gene–culture coevolution: once self-awareness and symbolic thinking began conferring advantages (better group coordination, planning, innovation), individuals and groups who adopted the “mind-enhancing” rituals could outcompete those who did not 66 67. Over time this would drive genetic selection for brains more adept at recursion and altered-state resilience. Interestingly, population genetics has identified a few brain-related gene variants that rose to near-fixation in humans after 50,000 years ago – suggesting relatively recent adaptive changes. A notable example is the gene Microcephalin (MCPH1), which regulates brain development. One haplotype of Microcephalin appears to have arisen around 37,000 years ago and swept rapidly through the population, now present in the majority of humans outside Africa 68 69. Scientists inferred that this variant spread under strong positive selection, reaching high frequencies in a short period (evolutionarily speaking) 68 70. Intriguingly, they also concluded that the Microcephalin variant likely originated from interbreeding with an archaic human lineage (possibly Neanderthals) – essentially a beneficial brain allele imported into H. sapiens and then amplified by selection 71 72. What trait it conferred is unknown (and studies have not found any simple effect on modern IQ 73 74), but the timing is suggestive: as one report noted, this genetic change “appears along with the emergence of such traits as art and music, religious practices, and sophisticated tool-making” tens of millennia ago 75 70. In other words, as culture was blossoming, our brains were still evolving. It’s conceivable that the spread of reflective consciousness itself created new evolutionary pressures – for instance, greater working memory to handle inner dialogue, or better emotional regulation to cope with existential awareness. One provocative hypothesis is that male lineages in particular might have undergone a cull or bottleneck during this transition. Some anthropologists have observed that genetic diversity of the Y-chromosome (passed through males) contracted severely in the last 50,000 years, more so than maternal lineages – implying that far fewer men than women were procreating in certain periods of prehistory. While warfare or clan dynamics could explain that, another angle is that conscious females would only mate with similarly conscious males, essentially driving non-sapient male lineages to extinction. The result would be a dramatic pruning of the family tree in favor of those with the spark of inner life. This speculative “Eve effect” dovetails with the many mythic tales of a select group surviving a great purge or flood to become the ancestors of all humans (for example, legends where only the people “awakened” by the gods are spared while others perish).

Even if the genetic imprint is subtle, the mythological imprint is loud and resonant. Myths are not fickle fictions – the oldest and most universal ones likely encode critical memories and teachings. Comparative mythologists find recurring motifs across continents: a time when humans lived in a mindless Edenic state, a transformative encounter with a serpent or trickster, a forbidden drink or fruit that grants knowledge, and the subsequent fall into self-conscious mortality 76 77. It is astounding that serpents are so consistently linked to primal knowledge in narratives from cultures that had no contact. In Mesoamerican lore, the god Quetzalcóatl (a feathered serpent) gave humans maize and learning. In some Aboriginal Australian stories, the Rainbow Serpent created humans and bestowed language and law 13. In the Rig Veda of India, the dragon-serpent Vritra hoarded the world’s waters and was slain to release prosperity – a metaphor for overcoming a blockage to wisdom. These could be independent inventions, but another explanation is cultural diffusion from a very ancient source. Recent computational phylogenetic analyses of myths (treating motifs like genes that mutate and diverge) have even proposed that the “dragon-slaying” story may trace back to the early Upper Paleolithic, carried out of Africa by the first modern humans tens of thousands of years ago 78 79. Although such analyses are contentious 80 81, they support the notion that a core complex of serpent mythology is extremely old. The Eve Theory interprets this complex not as pure coincidence but as a stylized record of real events: women (later remembered as “Eve” or a mother goddess) imparting the secret of the inner self, with a snake (literally used in rituals) as the sacrament or symbol of the awakening 14 82. The subsequent “Fall” – humans leaving a naive paradise and becoming aware of suffering and death – reflects the bittersweet nature of consciousness. We gained rich inner lives and spirituality, yet could no longer be at one with nature like other animals. Early consciousness might not have been entirely pleasant; evidence of trepanation (skull drilling) appearing globally in the Neolithic has been interpreted as attempts to cure headaches or madness – perhaps the byproducts of a newly introspective mind 83. Even certain psychopathologies like schizophrenia (involving hearing voices and delusions) could not exist before a sense of self emerged, and their appearance may have shaken early societies, spawning ideas of demonic possession or witchcraft 84. It’s telling that many cultures’ first heroes or demigods – from Gilgamesh to Prometheus – are those who stole some knowledge or fire from the gods, an act that often involved trickery and was punished. In the Eve Theory, the “trick” was leveraging snake venom to spark insight, and the “punishment” was that humans, once self-aware, were burdened with knowledge of mortality and moral choice.

Conclusion: A New Synthesis on Human Consciousness#

From fossils to folklore, disparate strands of evidence are converging on a dramatic story of how we became truly human. The Eve Theory of Consciousness synthesizes these strands: our species’ defining mental traits – self-awareness, language, symbolic art, spiritual yearning – may have co-arisen in a relatively brief epoch, midwifed by ritual and pharmacology. Women, with their social-attentive brains and central role in nurturing culture, could have been the first to break through, declaring “This am I!” and initiating others into that revelation. The unlikely hero of the story is the snake, not as a villain but as a catalyst – its venom providing the shock that pried open the human mind. What was once derided as the fanciful notion of a “Stoned Ape” evolution (Terence McKenna’s idea that psychedelic mushrooms drove brain expansion) now gains teeth, quite literally 85. Unlike random apes gobbling psilocybe mushrooms, the Eve scenario is grounded in known human behaviors: ritual group practices, initiation ordeals, and the global motif of serpent wisdom. It also leaves traces we can test – in genes under selection, in patterns of myth and symbols, and perhaps in archaeological residues of ancient ceremonies.

No single piece of this puzzle is ironclad. Each line of evidence – be it a cave painting of a snake, a genetic haplotype, or a legend of Eden – can invite alternative explanations. But together, they form a coherent and surprisingly empirical narrative about consciousness emerging as an “invention” our ancestors actively sought. As evolutionary psychologist Merlin Donald noted, the truly hard problem is explaining how our brain’s latent capacities were unleashed in the cultural explosion that distinguished us from even our anatomically identical forebears 86 87. The Eve Theory offers a multi-dimensional answer: through the insight of individuals (likely female), the discipline of ritual, the aid of neurochemical serendipity (venom), and the crucible of social transmission, humanity crossed a threshold.

In embracing this synthesis, we bridge science and the humanities – treating ancient scriptures and carvings as data alongside fossils and DNA. That integrative approach yields testable hypotheses: for example, researchers could look for correlations between snake species ranges and early human symbolic sites, or analyze whether societies with strong serpent myths have other echoes of entheogenic practices. Ongoing discoveries in neurobiology might reveal why certain toxins induce mystical experiences, lending biochemical credence to the idea that a venom-induced neural state could jump-start reflexive consciousness. Far from being a mere just-so story, the Eve Theory galvanizes an interdisciplinary quest. It challenges us to see our own minds as the product of not just biological evolution, but cultural and spiritual striving. In a sense, every time we tell the story of Adam and Eve or celebrate a rites-of-passage ceremony, we are commemorating that primal awakening. And if the theory is correct, the true “Eden” was not a lush garden but a state of innocent unselfconsciousness – and the true serpent was the knowledge (brought by women and snakes) that opened our inner eyes and cast us out into a world forever changed by the presence of the self.

FAQ#

Q1. What exactly is the Eve Theory of Consciousness?

A: It’s a hypothesis that human self-awareness arose relatively recently (around 50,000 years ago) through a cultural event – specifically, that women discovered introspective consciousness and spread it via serpent-centric initiation rituals. In this view, a combination of female social brains, trance-inducing practices (using snake venom), and subsequent gene–culture evolution sparked the “soul” in Homo sapiens, rather than a single genetic mutation or slow gradation.

Q2. How is this different from the Stoned Ape theory?

A: Terence McKenna’s “Stoned Ape” idea suggested our ancestors randomly ate psychedelic mushrooms which boosted their cognition. The Eve Theory is more specific and evidence-based: it proposes an organized, taught practice (ritual envenomation led by women) as the driver, rather than incidental mushroom foraging. It also has broader interdisciplinary support – drawing on anthropology, mythology, and archaeology – whereas Stoned Ape remains a speculative just-so story with little direct evidence (no clear mushroom artifacts, etc.). In short, Eve Theory gives the “stoned ape” a concrete cultural context and a globally attested symbol (the snake).

Q3. Is there archaeological evidence of a prehistoric snake cult or ritual?

A: Indirect evidence exists. For example, a cave in Botswana has a 6-meter rock resembling a python with artifacts dating to ~70,000 years ago, which some archaeologists interpret as a ritual site for Python worship (though debated) 63. Many later prehistoric sites (Neolithic onwards) do show snake iconography associated with goddesses, tombs, and healing sanctuaries. While we don’t yet have a “smoking gun” of venom use (like residue in a ritually punctured bone), the ubiquity of serpent symbols in early art and religion – and their link to transformative knowledge in myths – strongly suggests snakes held a sacred role for early humans consistent with the theory.

Q4. Couldn’t language alone explain the emergence of consciousness?

A: Language is certainly a key part of human cognition, and some scholars argue that recursive grammar enabled complex self-reflection 88 89. However, language evolution doesn’t fully resolve the puzzle – we don’t know why language appeared when it did. The Eve Theory complements linguistic explanations by suggesting an experiential trigger: rituals that gave content to the notion of an “I”. In fact, language and ritual likely co-evolved; teaching someone to say “I am” in a meaningful way may have required a profound subjective experience to anchor those words. The theory doesn’t deny language’s importance – it contextualizes it within a broader cultural awakening, implying that inner speech (talking to oneself internally) was both a cause and effect of gaining consciousness.

Q5. What role did Neanderthals or other humans play in this scenario?

A: If the Eve Theory’s timing is correct, the awakening of consciousness happened in Homo sapiens after the out-of-Africa migration, and perhaps after or during encounters with Neanderthals. There is speculation that interbreeding with Neanderthals contributed certain brain-beneficial genes (for example, the Microcephalin variant that swept through humans ~37k years ago 68 75). It’s possible Neanderthals had some capacity for symbolism (they buried their dead and made simple art), but there’s scant evidence they experienced the full “inner spark” as we do. The theory would suggest that while Neanderthals could learn behaviors through contact, they might not have independently developed the consciousness cult. Interestingly, many folklore traditions (and even 19th-century mythographers) imagined “older” human-like beings without souls (giants, etc.) who perish or are outcompeted when true humans (with souls) arrive. This mirrors the idea that H. sapiens undergoing the Eve revolution supplanted contemporaries like Neanderthals, either by conflict or simply by being more cognitively adaptable.

Footnotes#

Sources#

- Renfrew, Colin. “Solving the ‘Sapient Paradox’.” BioScience 58(2) (2008): 171–172. doi:10.1641/B580212. A brief introduction to the puzzle of why anatomically modern humans waited so long (till the Upper Paleolithic) to express modern behavior 1 87.

- Lewis-Williams, David, and T. A. Dowson. “The Signs of All Times: Entoptic Phenomena in Upper Paleolithic Art.” Current Anthropology 29(2) (1988): 201–245. doi:10.1086/203625. Classic paper arguing that abstract cave art motifs correspond to hallucinations seen in trance states, linking prehistoric art to shamanic altered consciousness 30 26.

- Ruck, Carl A. P. “The Myth of the Lernaean Hydra.” in Pharmacology in Classical Antiquity (2016): 137–154. (ResearchGate). Documents evidence that ancient Greeks used snake venom in psychoactive rituals, with references to milking serpents for entheogenic “unguents” 8 55 and hints from myth (Hydra, Medusa) as allegories for drug use.

- Stutesman, Drake. Snake (Reaktion Books “Animal” series). London: Reaktion, 2005. Cultural history of snakes. Notably mentions that at Delphi, priestesses (Pythonesses) were rumored to ingest snake venom to induce prophetic trances 45 57, and recounts modern reports of hallucinations from snakebite 46.

- Grosman, Leore, and Natalie D. Munro. “A 12,000-year-old Shaman Burial from the Southern Levant (Israel).” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107(23) (2010): 15362–15366. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005765107. Reports the discovery of an elderly female buried with ritual paraphernalia at Hilazon Tachtit, interpreted as the grave of a Natufian shaman 15 41. This provides early archaeological evidence of female ritual leaders.

- Greenberg, David M., et al. “The ‘Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ Test: A Massive Cross-Cultural Study.” PNAS 119(28) (2022): e2123143119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2123143119. Largest study to date on theory-of-mind sex differences, finding that females scored higher on cognitive empathy across 57 countries 6 34. Supports the idea of a female advantage in social-cognitive processing.

- Asperholm, Martin, et al. “What Did You Do Yesterday? A Meta-Analysis of Sex Differences in Episodic Memory.” Psychological Bulletin 45(8) (2019): 785–821. doi:10.1037/bul0000197. Meta-analysis of 617 studies (1.2 million participants) showing a slight overall female advantage in episodic memory, especially for verbal and face-recognition tasks 35 36. Male advantage was found in spatial memory. This cognitive dimorphism is relevant to the Eve Theory’s emphasis on women’s memory and “mental time travel.”

- Evans, Patrick D., et al. “Evidence that the Adaptive Allele of the Brain Size Gene Microcephalin Introgressed into Homo sapiens from an Archaic Homo Lineage.” PNAS 103(48) (2006): 18178–18183. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606966103. Genetic study showing a Microcephalin variant arose ~37,000 years ago and swept to high frequency under selection 68 70, possibly via Neanderthal introgression 72. Indicates continued brain evolution concurrent with the cultural “Great Leap Forward.”

- Lahn, Bruce T., et al. “Microcephalin, a Gene Regulating Brain Size, Continues to Evolve Adaptively in Humans.” Science 309(5741) (2005): 1717–1720. doi:10.1126/science.1113722. (See also Mekel-Bobrov et al. 2005 on ASPM.) Reports that a specific Microcephalin haplogroup (D) spread starting ~37kya, and an ASPM variant ~5.8kya, suggesting recent selection on brain-related genes 68 75. Connects the Microcephalin timeline to the emergence of symbolic culture in the archaeological record 75.

- Froese, Tom. “Ritualized Altered States and the Origins of Human Self-Consciousness.” (2013). In press theory outlined in various talks/papers (e.g., Froese 2015 Physics of Life Reviews commentary). Proposes that deliberate inductions of altered consciousness (via ritual) were crucial to developing an observer stance in early humans 24 23. Froese’s ideas underpin the Eve Theory’s core mechanism, highlighting subject–object separation achieved through shamanic initiation practices rather than gradual neural change alone.

- d’Huy, Julien. “The Dragon Motif may be Paleolithic: Statistical Mythology in Worldwide Comparison.” Preprint (2012) HAL archives 92 79. Applies phylogenetic analysis to serpent/dragon myths across cultures, suggesting a common origin possibly >30,000 years old. While controversial 80, this research underscores the antiquity of snake-related mythologemes and their potential diffusion with early modern humans.