TL;DR

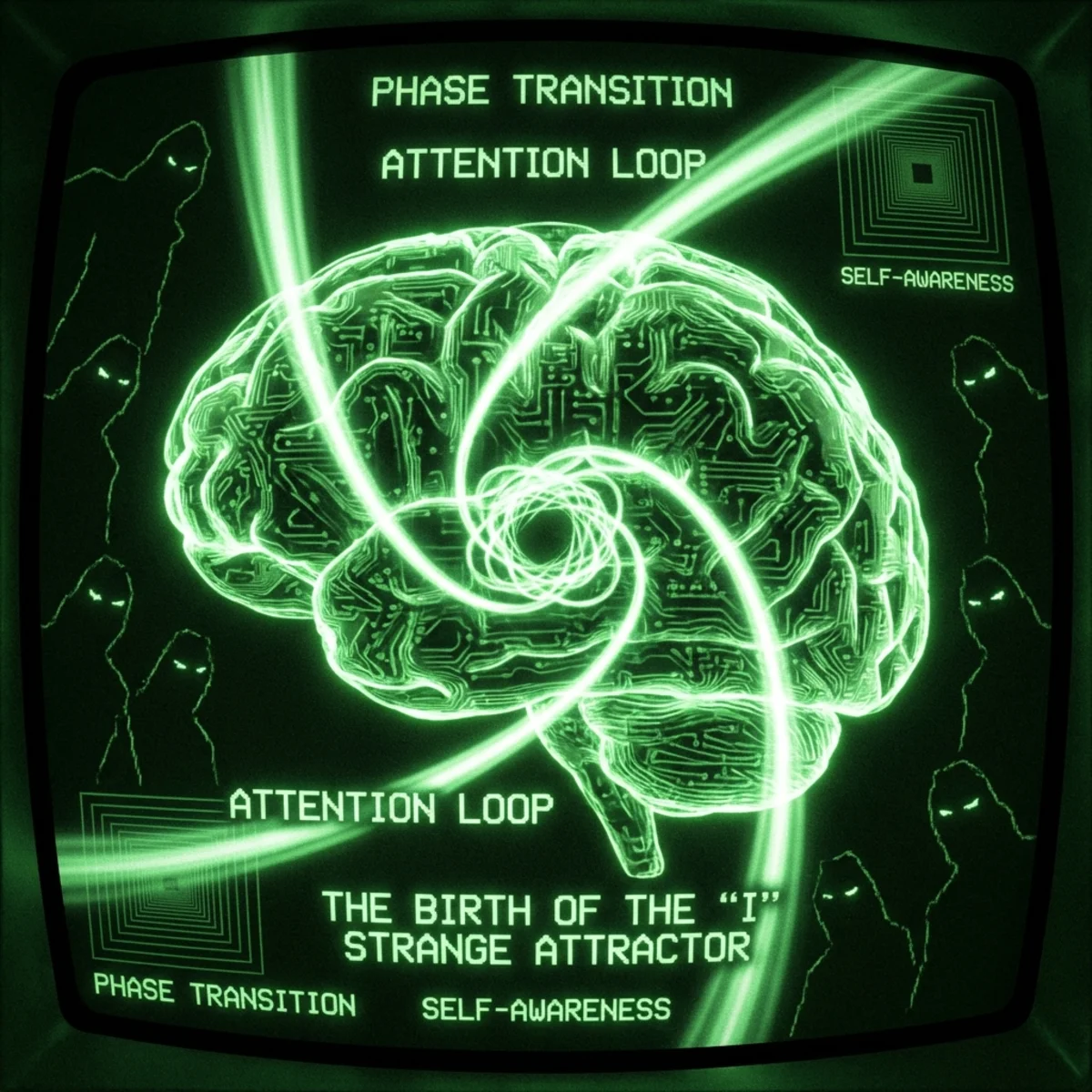

- The Eve Theory of Consciousness (EToC) argues that self-aware consciousness arose from a gene-culture interaction that made human attention recursive (self-referential).

- This “knot” in attention created a stable “I” and addresses the Sapient Paradox—the gap between anatomically modern humans and behaviorally modern ones.

- EToC suggests a cultural trigger (like a ritual) unlocked this recursive potential around 15,000 years ago, which was then reinforced by genetic selection.

- This model aligns with major consciousness theories like Integrated Information Theory (IIT) and Global Workspace Theory (GWT), providing a historical timeline for when the brain’s complexity crossed a critical threshold.

Introduction: The Eve Theory of Consciousness as a Gene–Culture Evolution of Recursive Attention#

The Eve Theory of Consciousness (EToC) proposes that human consciousness – in particular, self-aware, reflective consciousness – is a relatively recent innovation that arose from a gene–culture interaction affecting how attention is structured. In this view, our ancestors underwent a cognitive phase transition when attention “turned inward” and became recursive (self-referential). This recursive attention created a kind of evolutionary “gravity well,” quickly proving adaptive and reshaping both culture and genes. Here we reframe EToC in these terms and explore how it aligns with major theories of consciousness. We will see that EToC essentially posits an evolutionary knot tied in the fabric of attention – attention pointed at itself – and that this leap may correspond to a sudden increase in brain integratedness and global self-modeling, much as theories like Integrated Information Theory and Global Workspace have suggested (albeit without an evolutionary timeline). We assume an expert audience; the goal is to accurately synthesize EToC’s model from ~60,000 years ago to the present, and show how it resonates with well-known frameworks (IIT, Global Workspace, higher-order theories, Attention Schema, etc.) without distorting any of them or EToC.

The Puzzle of Late-Arising Modern Consciousness#

Paleoanthropology presents a curious gap between our anatomical evolution and our cognitive behavior. Homo sapiens appeared ~200,000 years ago, yet for most of that time there is scant evidence of the behaviors we consider “sapient.” Stone tool designs stagnated for tens of millennia; art and symbolism were practically nonexistent. It’s only around 50,000 years ago that we see a “Great Leap Forward” in cultural creativity – more advanced tools, cave paintings, body ornaments, probable burials with ritual, etc.. Many anthropologists equate this with the dawn of inner life: the emergence of language, symbolic thought, and perhaps the first glimmers of introspective self-awareness. And yet, even after 50kya, progress was uneven – true large-scale innovation (agriculture, civilization) didn’t ignite until ~12–15kya, at the end of the last Ice Age. This lag between having a modern brain and expressing modern behavior is known as the Sapient Paradox. As Renfrew noted, from a distance it looks as if the Sedentary (Agricultural) Revolution ~12kya was the real “Human Revolution” all along.

EToC directly addresses this paradox. It asserts that consciousness in the full sense (sapience, self-aware mind) did not arrive automatically with our species’ anatomical origin, but flowered later as a result of an event or process that made attention recursive. The timeline it suggests is roughly: an initial capacity for recursion arose genetically by ~60kya, but the actual realization of self-reflective consciousness happened much later, perhaps ~15kya, precipitating the cascade of behavioral modernity. This stance is a modern twist on Julian Jaynes’s famous (and controversial) idea that consciousness is a learned trait that had a historical beginning – though Jaynes placed it around 1200 BCE, which EToC finds far too late. Instead, EToC times the “Big Bang of the mind” to the late Pleistocene, aligning with real archaeological signals of cognitive change. For example, anthropologist Thomas Wynn scoured the record for signs of abstract thought and found none unequivocal before ~16,000 years ago. Even the earliest plausible sign – groupings of cave art symbols by gender at Lascaux – appears only ~16kya and is debated. It seems something fundamentally shifted in that window, enabling formal symbolism and abstract categorization for the first time. In short, the evidence hints that our ancestors experienced a phase change in cognition rather late, which then globally “switched on” the suite of behaviors we now recognize as uniquely human.

Recursive Attention: Tying a Cognitive Knot#

What was the nature of this phase change? EToC’s answer: the structure of attention became recursive. In plain terms, attention learned to attend to itself. Instead of just perceiving the world, the human mind began to perceive its own perceptions – to have thoughts about its thoughts, feelings about its feelings. This self-referential looping of mental content is essentially metacognition, or an internal feedback loop of awareness. One might poetically say that around this time we pointed the flashlight of attention back at the mind itself, creating a hall of mirrors. The Eve Theory metaphorically describes it as “tying a knot” in the fabric of thought: a closed loop that hadn’t existed before. Once that knot was tied, it created a stable reference point – an “I”. The mind could now represent itself inside itself, which is the essence of self-awareness. Cognitive scientist Michael Corballis and others have long argued that recursive thinking is the linchpin of human cognition, underlying language (with its nested phrases), self-awareness, mental time-travel, and more. The entire human package, Corballis says, might be “tightly wound up by a single principle” – recursion. EToC builds on this idea but grounds it in an evolutionary narrative: at a specific point, our ancestors achieved that recursive principle within their attentional apparatus. Before then, they may have been intelligent and communicative, but they lacked the recursive structure that produces an introspective soul or ego.

It’s important to clarify that by “consciousness” here we mean the reflective, autobiographical form of consciousness – sometimes called sapience, self-awareness, or having an “inner voice.” EToC does not claim our predecessors were zombies with no sensations or learning; rather, it suggests they operated more like other animals – perceiving and reacting, perhaps even speaking in a basic way – but without a concept of “I” binding their experiences. Their attention was likely focused outward or on immediate tasks; they did not reflect upon attention itself. When a modern human introspects (“What am I feeling? Why did I think that?”), we are exercising this strange ability to mentally model our own mind. EToC pinpoints the origin of that ability. In effect, humans crossed from merely noetic awareness (knowledge of the world) to autonoetic awareness (knowledge of self in the world). Psychologist Endel Tulving used “autonoetic consciousness” to denote the capacity to reflect on one’s own experiences and place oneself in time, which he believed to be uniquely developed in humans. EToC’s proposed Paleolithic shift could be seen as the birth of autonoetic, self-modeling cognition – a recursive loop that suddenly allowed Homo sapiens to know that they know, to feel that they feel. This was a singularity in the mind: a small change in architecture (a new feedback loop) yielding an entirely new phenomenological universe.

Before vs. After: Attention Without and With Self-Reference#

To better grasp the impact, we can contrast pre-recursive minds with post-recursive minds. • Before (~60k+ years ago): Humans were anatomically modern and may have had the neural capacity for complex thought (perhaps enabled by a genetic mutation for recursive syntax around 60–100kya, as Chomsky has conjectured ). However, in practice their cognition remained behaviorally archaic. Attention was likely stimulus-driven and oriented to external needs – finding food, navigating social hierarchies, basic tool use. Any language was concrete and imperative (simple commands, immediate references), lacking rich grammar or introspective vocabulary. Crucially, there was no sustained inner monologue, no sense of an internal “mind’s eye” that could observe memories or imagine novel scenarios at will. If you could time-travel and meet a human 60k years ago, you’d find a creature with keen perception and clever instincts, but one who lacked reflection. They might not recognize themselves in a mirror or ponder the motivations of others in the abstract. Culturally, this meant tens of thousands of years of comparative stasis and simplicity: tools that hardly changed across generations, almost no art or ornamentation, and no evidence of myth or existential contemplation. In essence, humans were social animals with clever brains, but not yet self-aware beings weaving narratives about themselves. • After (~15k years ago and beyond): We see the dawn of what paleoanthropologists call Behavioral Modernity – a global blossoming of innovation and symbolism. The archaeological record “switches on”: sophisticated cave paintings and carvings appear, human burials with grave goods become common (implying ritual and afterlife beliefs), ornamental and stylistic variation in tools and personal adornments explode (implying identity and art), and within a few millennia we have early villages, agriculture, and the long march to civilization. EToC argues these are the outward signs that attention had turned inward. A mind with recursive attention can generate complex plans (e.g. imagining a crop cycle across seasons, which is vital for agriculture) and can innovate by mentally simulating alternatives. It also gains a sense of meaning – hence the flowering of religion and myth to explain that new inner world. Most tellingly, we see evidence of true symbolic thought: by 15–10kya, humans start to create abstract signs and perhaps early writing marks , and concepts like gender, value, and social roles become more salient in art. These suggest minds able to categorize the world conceptually (“mammoths are different from horses in principle, perhaps male vs female symbols” as one reading of cave art goes ). Such abstraction is a hallmark of recursive, self-referential thinking – one can only conceive symbols (things that stand for other things) when the mind can hold an idea and simultaneously hold the idea of oneself holding the idea. In short, after the “knot” in attention, humans behave like conscious actors: self-driven, imaginative, story-telling, and self-regulating in a way qualitatively distinct from their pre-recursive ancestors. It is as if a light was turned on in the mental universe, and all subsequent history was illuminated by it.

Crucially, EToC suggests this transformation was not spread out gradually over 100,000 years but was more phase-like – a tipping point was reached and then a rapid transition followed. The notion of a phase transition is apt: below a certain threshold, the system (the human brain/mind) was in one stable state (no persistent introspection); once that threshold was crossed, a new stable state emerged (a mind that relentlessly self-reflects, for better or worse). Like water turning to ice, there is a discontinuity: the integrative capacity of the brain might have crossed a critical point when recursion arrived, snapping into a new configuration. The “before and after” were stark – as different as a non-verbal animal’s mental life is from our own, yet happening within the same species.

Gene–Culture Coevolution: How Culture Taught the Brain to Be Conscious#

How could such a radical change occur? EToC’s answer lies in gene–culture coevolution. The idea is that a cultural innovation (some practice or communication) triggered the shift in attention, and once that happened, it created strong selection pressure on our genes to support the new mode of thinking. In other words, culture first unlocked recursive consciousness, then biology “locked it in.”

Genes set the stage#

It’s likely that by ~60kya the human brain was capable of recursion in principle – for example, some mutation might have endowed us with a more recursive language faculty or more flexible prefrontal circuits. (Noam Chomsky famously speculated that a single genetic mutation gave rise to universal grammar, essentially a recursive combinatorial ability, around that time.) However, having the hardware potential doesn’t guarantee the software will spontaneously run. For thousands of years, that potential lay mostly dormant or only minimally expressed – much like having a powerful computer with no programs taking advantage of its full power. The archaeological “silence” after 60k suggests that whatever genetic changes occurred did not immediately revolutionize behavior. Something more was needed to kick-start the recursive loop.

Culture pulls the trigger#

EToC hypothesizes that the trigger was likely some form of ritual, symbol, or communication that induced the first instance of true self-referential attention. One intriguing proposal in EToC is the idea of a proto-spiritual ritual involving snake venom. The story goes that a prehistoric human – possibly a woman, hence “Eve” – was bitten by a venomous snake and survived, but in the altered neurochemical state caused by the venom, she experienced something utterly novel: a vision of “herself.” In modern terms, the neurotoxins (some venoms have psychoactive effects ) might have disrupted normal sensory processing and induced a hyper-real dream or out-of-body state where the person suddenly perceived their own mind from the inside. This would be the inaugural “I am” moment – literally a poisoned apple of knowledge, to draw on the Garden of Eden metaphor. If that woman (or anyone in that scenario) then conveyed the experience to others, it could catalyze imitative practices: deliberate envenomation rituals to replicate the insight. EToC suggests women might have pioneered this partly because, as gatherers and caretakers, they handled animals (including snakes) and psychotropic plants more and could be the first experimenters. The Biblical story of Eve and the Serpent tempting with knowledge is viewed not as coincidence but as a mythic echo of this very real prehistoric breakthrough. Indeed, serpent symbols are pervasive in ancient myths of wisdom across the world, and EToC interprets this as cultural memory of a “snake cult” of consciousness that arose in the late Ice Age and spread widely.

Whether or not snake venom was the specific catalyst, the general mechanism is mimetic and cultural: a few individuals stumble upon a method to induce reflexive consciousness (through psychoactive substances, trance, meditation, or some cognitive technique), and teach others this method. Anthropologically, this might look like shamanic initiation – a controlled ordeal that produces a transformative inner experience. EToC aligns with Jaynes’s suggestion that consciousness might initially be a learned, transmitted skill , except placing it much earlier than Jaynes did. In a striking phrase, the theory proposes “consciousness as a taught behavior”. Essentially, early “Eves” taught their tribes how to have an inner voice – perhaps through guided introspection, storytelling, or ritualized ingestion of mind-altering substances to reveal the self. This idea flips the script on how we usually think of consciousness; rather than purely an emergent biological accident, it was actively discovered and shared by humans through culture. It also means it could appear first in one or a few groups and then diffuse rather than needing to evolve in parallel everywhere.

Genes reinforce the change#

Once self-awareness and recursive thinking started spreading memetically, it dramatically changed the rules of survival. Individuals who had the inner spark could coordinate better, plan farther ahead, and accumulate knowledge, out-competing those who remained essentially on “auto-pilot.” In evolutionary terms, a new selection pressure had emerged: the cognitive “game” now favored those who could handle recursion – rich language, symbolic thought, theory of mind, etc.. Consequently, any genetic variations that supported these traits would be strongly selected for within a few millennia, which is a blink of an eye in evolution. Recent analyses of the human genome indeed show evidence of continued selection on brain-related genes in the Holocene (the last ~10k years). One example EToC highlights is TENM1 (Teneurin-1) – a gene involved in neuroplasticity and brain development, especially in limbic circuits. TENM1 shows one of the strongest signals of recent positive selection in humans (notably on the X chromosome). Tellingly, its function relates to regulating BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor), which governs neural plasticity and learning. In the EToC narrative, one can imagine that early consciousness-raising practices (say snake venom exposure) flooded the brain with nerve growth factors and demanded extreme neural rewiring. Those humans with genes that gave more robust plasticity (e.g. higher BDNF via TENM1) would better withstand and integrate the experience, thus gaining more from the newfound introspection. Over generations, such genes would spread, making the capacity for stable self-awareness more universal. As one commentator summarized: “gene-culture coevolution would lock in what the snake cult unlocked.” In other words, culture opened the door, and then genes built a doorstop to keep it open permanently.

This feedback loop explains why consciousness, once introduced, did not fade out but instead became entrenched. It also elegantly accounts for how all humans today share this trait: even if only a small population developed recursive consciousness initially, cultural diffusion plus later genetic intermixing could spread it to all lineages. (Not every group needed the exact same mutation or epiphany; one origin could suffice, unlike if it were a hardwired trait that had to mutate everywhere independently.) Indeed, humanity’s interconnected breeding over the Holocene means even a late-arising advantageous gene can become nearly universal – our most recent common ancestors may have lived only ~5-7kya , indicating substantial mixing. Thus, EToC’s timeline is plausible: a singular “Eve” event ~15kya can lead to a world of conscious beings by today, via memetic contagion followed by genetic assimilation.

To summarize this coevolution: the cultural evolution of a recursive attention mind created a niche in which having a brain optimized for such recursion was highly fitness-enhancing. The result was a self-reinforcing spiral – culture and genes driving each other toward deeper integration of thought. In evolutionary landscapes, this was a gravity well: once a population fell into this attractor state of being self-aware and symbol-using, it would be very difficult (if not impossible) for it to revert to an unconscious state, because all adaptive paths now led further into reflective cognition. The human lineage, in effect, domesticated its own mind during the Holocene, akin to how it domesticated plants and animals. We selected ourselves for better learning, communication, and introspection, sculpting brains increasingly adept at sustaining the “I” and all its wonders.

Before moving on, it’s worth noting how radical this perspective is. It implies that for a huge span of time, anatomically modern humans were not consciously self-aware in the way we are – an idea that can be unsettling. Yet it makes sense of otherwise baffling data (e.g. the long static stretches of the Paleolithic). It also recasts ancient myths not as naïve stories but as encoded collective memories. EToC leans on the possibility that myths of paradise, the serpent, the “Fall” (the loss of our original unselfconscious innocence) are folk recollections of this very real cognitive revolution. For example, nearly every culture has some form of serpent in its cosmology (often as giver of wisdom or immortality), and many have flood myths, mother goddesses, etc. EToC suggests these are not arbitrary – they cluster around the late glacial/early Holocene transition, hinting that people were mythologizing the profound changes they were undergoing. In short, our cultural and even genetic story bears the imprint of an attention that learned to look back at itself.

Consciousness Theories and the Recursive Phase Change#

Strikingly, the scenario described by EToC – a jump to recursive self-modeling minds – resonates with many leading theories of consciousness in neuroscience and philosophy. EToC could be seen as describing when and why the brain moved into a regime that these theories consider necessary for conscious experience. Let’s weave in a few such theories and show the parallels:

- Integrated Information Theory (IIT) – a Phase Transition in Integratedness: IIT (Tononi et al.) posits that consciousness corresponds to the amount of integrated information (denoted Φ) generated by a system of elements. Crucially, for high integration to occur, the system needs reentrant loops and feedback. In other words, recursion is physically required for consciousness in IIT. The introduction of a self-referential attention loop could have been the catalyst that hugely amplified Φ, pushing the brain over some critical threshold where a unified conscious field “lit up.”

- Global Neuronal Workspace – Recursion Enables Global Broadcast: Global Workspace Theory (GWT) holds that consciousness corresponds to global broadcasting of information across the brain’s networks. A recursive attention system might be necessary to stabilize complex self-referential content in the workspace. In effect, once the brain could not only send data to a global workspace but also include an internal self-model in that workspace, it achieved a new level of broadcasting: ideas like “I am seeing X” could circulate.

- Higher-Order Theories – The First “Thoughts about Thoughts”: Higher-order theories of consciousness (HOTs) assert that a mental state is conscious only if there is a higher-order representation of that state in the mind. EToC’s claim that consciousness arose from attention turning on itself is essentially a description of a higher-order thought emerging in evolution. It provides a historical context for HOT: the invention/discovery of higher-order representation as a cognitive skill.

- Attention Schema Theory (AST) – Evolution of the Self-Model of Attention: AST (Graziano) says the brain constructs an internal model of attention. This self-model of attention is what the brain identifies as “awareness.” One interpretation is that perhaps the human brain did not always have an attention schema. EToC could be describing the evolutionary origin of the attention schema.

- The Self as a Strange Loop: The idea that the self emerges from a recursive feedback loop (Hofstadter) is embodied by EToC. At ~15kya, minds that were previously directed outward formed a closed loop of self-observation – a strange feedback cycle where the thinker became part of what was thought about. Once stable, this loop gives the illusion of a persistent self.

Each of these theoretical perspectives converges on the idea that consciousness involves some kind of recursive, self-referential information structure. EToC is saying that structure did not always exist in our species but emerged through evolutionary and historical processes.

Consequences of the Recursive Mind – The Gravity Well of Selfhood#

Once recursive self-awareness took hold, it unleashed a cascade of consequences, virtually all the traits we think of as distinguishing humans. This is why EToC describes it as creating a “gravity well” – an attractor state that everything else fell into because of its fitness and novelty. Here are some key consequences:

- Enhanced Planning and Foresight: A creature with an inner eye can simulate possible futures. This future-oriented consciousness is what ultimately led to the Agricultural Revolution.

- Explosion of Creativity and Symbolism: With self-awareness comes an urge to express and externalize inner experiences. Symbolism itself is a recursive concept.

- Narrative Self and Myth-making: A newly conscious being, suddenly aware of mortality and purpose, needs explanations. This led to myths, spiritual systems, and the concept of the soul.

- Language Flourishment (and Pronouns): Recursive thought would encourage more complex language to describe newfound inner states. Pronouns like “I” and “me” are recursive labels.

- Social and Moral Complexity: A recursive mind allows for a robust Theory of Mind—the ability to model the thoughts and intentions of others, enhancing empathy, deception, and cooperation.

Conclusion: Tying It All Together#

The Eve Theory of Consciousness, viewed through the lens of attention and gene–culture evolution, offers a bold narrative: human consciousness (as we know it) was an evolutionary innovation – a phase change triggered by making attention recursive and self-referential. This portrayal dovetails with many theoretical understandings of what consciousness is.

By grounding the discussion in evolution and archaeology, EToC reminds us that consciousness has a history. It demystifies some of the discontinuity: those puzzling gaps (the long stasis followed by sudden cultural fluorescence) are not because humans mysteriously “decided” to paint caves one day, but because the internal prerequisites fell into place.

Ultimately, framing EToC as the evolution of a new attention structure highlights a profound lesson: consciousness is not only a state to be explained, but also a strategy that evolution stumbled upon – a strategy of the brain modeling itself, which proved so advantageous that it reshaped the world.

FAQ#

Q 1. What is the core idea of EToC in terms of attention?

A. EToC proposes that human self-awareness began when our capacity for attention became recursive, meaning it could turn inward and observe itself. This created a stable self-model, or an “I,” which transformed human cognition.

Q 2. How does EToC explain the “Sapient Paradox”?

A. It suggests that anatomically modern humans existed for a long time with the potential for consciousness, but a cultural innovation (like a ritual) was needed to “activate” recursive attention and unlock behavioral modernity, explaining the lag.

Q 3. What is gene-culture coevolution in this context?

A. EToC argues that culture first taught the brain to be conscious (e.g., through rituals), and this new cognitive environment then created selection pressure for genes that better supported stable, recursive thought.

Q 4. How does this theory relate to other theories of consciousness like IIT or GWT?

A. EToC provides an evolutionary timeline for the emergence of the very structures that these theories see as essential for consciousness, such as high integrated information (IIT) or a global workspace capable of self-representation (GWT).

Q 5. What was the “gravity well” of selfhood? A. This is EToC’s metaphor for the powerful adaptive advantages conferred by recursive consciousness. Once achieved, traits like advanced planning, creativity, and social complexity made it an irreversible and self-reinforcing evolutionary path.

Footnotes#

Sources#

- The concepts and timeline of the Eve Theory of Consciousness are drawn from Andrew Cutler’s work, which synthesizes archaeological evidence of a late cognitive revolution with the idea of recursive thinking as the core of language and self-awareness.

- The gene–culture coevolution aspects, including recent selection on brain genes like TENM1 and the role of snake symbolism, are discussed in Cutler’s collaboration and commentary.

- Connections to major consciousness theories include Integrated Information Theory’s requirement for reentrant loops, Global Workspace’s global integration threshold, Higher-Order Thought’s emphasis on thoughts about thoughts, and Graziano’s Attention Schema Theory which describes awareness as the brain’s model of itself focusing on something – all of which align with the idea of a self-referential attention mechanism. These sources and theories collectively support the reframing of EToC as an evolutionary phase transition in the integrated, self-modeling capacity of the brain, marking the true dawn of human-like consciousness.