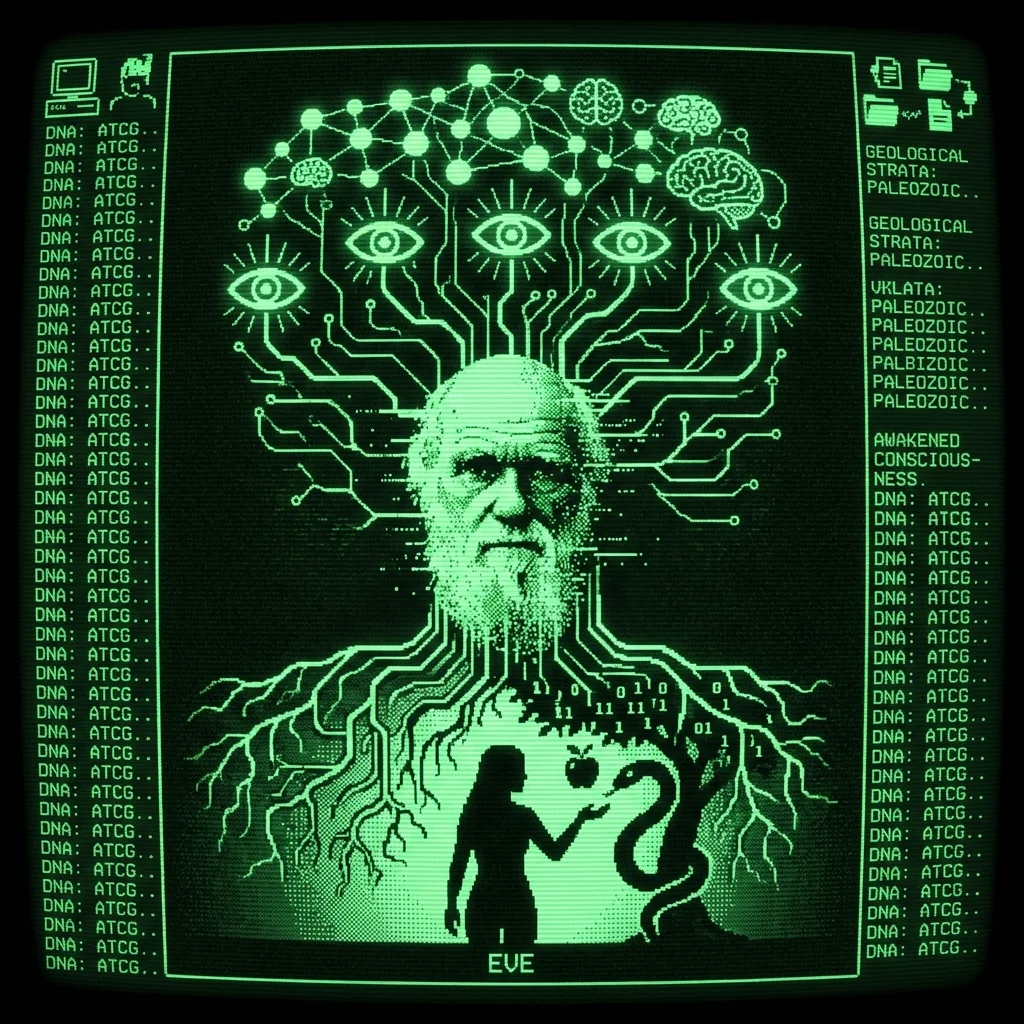

TL;DR

- Charles Darwin struggled to explain how the human mind and self-awareness arose through evolution, calling it a “problem for the distant future” [^oai1].

- Modern evidence shows a cultural “Great Leap” ~50,000 years ago when art, complex tools, and symbolic thinking suddenly flourished 1, suggesting a late evolutionary step in consciousness.

- The Eve Theory of Consciousness (EToC) proposes that women were the first to develop inner self-awareness (“I am”), using early rituals (possibly involving snake venom psychedelics) to spark and teach this soul-like self to others 2.

- This theory aligns with Darwin’s natural selection: individuals with even slight recursive thinking (self-reflective, language-capable thought) would have left more offspring, spreading those traits rapidly 3.

- Global mythology and genetics surprisingly support EToC – many cultures recall a time when women held sacred knowledge and men “took it” 4 5, and X-chromosome genes linked to brain development show signs of extraordinary recent selection 6.

- Darwin would likely be intrigued by EToC’s synthesis of evolution, anthropology, and myth, as it offers a material explanation for the “human soul” and addresses questions he posed but couldn’t answer, though he would insist on rigorous evidence and gradualist caution in interpreting such a bold hypothesis 7 8.

Darwin’s Puzzle: The Evolution of Consciousness#

Charles Darwin, the father of evolutionary theory, was deeply curious yet cautious about how human consciousness could have arisen from animal precursors. In the 19th century, he recognized that the mental gap between humans and other animals is vast—no ape composes symphonies or reflects on its existence—yet he maintained it was a difference “of degree and not of kind” 9. Darwin saw continuity in nature: even traits like memory, curiosity, or reason exist in rudimentary form in animals, and perhaps self-awareness emerged gradually from such faculties 9. If something like self-consciousness was uniquely human, Darwin suggested it might be an “incidental result” of our advanced intellect and especially our capacity for language 10. Language, to Darwin, was a key evolutionary innovation— a “half-art, half-instinct” that evolved over time 11 and could unlock abstract thought and the concept of “I”.

Despite these insights, Darwin admitted that explaining consciousness was exceptionally challenging. In Descent of Man (1871), after exploring the continuity of mental abilities, he conceded: “In what manner the mental powers were first developed in the lowest organisms is as hopeless an enquiry as how life itself first originated.” [^oai1] In other words, the origin of the mind’s spark was a mystery he would leave to the “distant future” [^oai1]. He could not pinpoint when or how our ancestors first experienced true self-awareness. At Darwin’s time, fossil and archaeological records of human prehistory were scant; the deep timeline of humanity was only beginning to be understood. Yet Darwin suspected that, just as an infant gradually becomes self-conscious 11, our species must have developed mind and soul stepwise, over many generations. The problem was determining when and why that final step occurred.

Darwin’s Perspective on Mind and Soul#

Darwin approached the human mind as a natural phenomenon, shaped by the same laws that govern animal evolution. He famously observed that even our loftiest faculties—morality, religion, reason—could have primitive analogues or precursors in animals 9. For example, animals exhibit emotions, social instincts, and basic problem-solving. If one argues that capacities like self-awareness or abstract thought are utterly unique to humans, Darwin countered that they likely arose as by-products of other evolving abilities (and especially our sophisticated use of language) 10. At what point does a child recognize itself as an “I”? he mused, noting that even in human development we cannot draw a sharp line 11. By analogy, there wouldn’t be a single moment when an ape ancestor woke up fully human—rather, there would be a continuum of mental evolution.

Yet Darwin also acknowledged how extraordinary the “immense” gulf is between a human’s mind and an ape’s 12 13. Humans ponder God, contemplate the stars, create art and philosophy—activities that are far beyond even the smartest chimpanzee. He listed unique traits: language, which allows expressing infinite ideas; metaphysical reasoning; moral sense and altruism beyond kin; and an existential self that can imagine its own mortality 14 13. These were part of what many would call the “soul” or the spiritual essence of humans. Darwin used the term cautiously, but he understood why people saw something almost supernatural in human self-consciousness and conscience. The challenge for science was to explain this spark of inner life in evolutionary terms, without invoking miracles. Darwin held out hope that natural selection over long periods could account for even our self and soul, and he opposed any suggestion (like from his colleague Alfred R. Wallace) that a “higher intelligence” must have intervened15. Still, in his era, concrete evidence was lacking.

By Darwin’s death in 1882, the puzzle remained: our brains had evolved from ape brains, yet somewhere along the line our ancestors began talking, imagining, and introspecting, fundamentally changing the rules of survival. When did that happen, and how? Darwin could not know. But today’s science provides clues that would fascinate him.

The Great Leap: Modern Clues of a Consciousness Revolution#

In the decades since Darwin, researchers have uncovered a startling pattern in the story of Homo sapiens. While our species arose anatomically around 200,000–300,000 years ago, there’s little sign of “modern” behavior for the majority of that time 1. For over 150,000 years, early humans made the same simple stone handaxes and spears with no notable innovation. Then, around 50,000 years ago, something changed dramatically. Archaeologists call this the onset of Behavioral Modernity or the Upper Paleolithic Revolution: a profusion of new tool types, personal ornaments and artwork (cave paintings, carved figures), the first evidence of long-distance trade, ritual burials, and other cultural explosions appearing almost like a “big bang” of the human mind 1 16. In Darwin’s terms, it’s as if our ancestors suddenly began to truly think and symbolize, whereas before they lived in a more animal-like cognitive state. Many paleoanthropologists, such as Richard Klein, argue that fully modern behavior arose quite suddenly in this timeframe rather than gradually 17#::text=50%2C000%20years%20ago%2C%20began%20spreading,1). Klein points out that around 50–40 kya (thousand years ago), humans expanded out of Africa and rapidly out-competed other hominids like Neanderthals, suggesting a newly superior intellect or communication ability 17#::text=paleoanthropology%20%2C%20Africa%20and%20Europe,1) 17#:~:text=50%2C000%20years%20ago%2C%20began%20spreading,1).

What could have caused this Great Leap Forward? One leading idea is the advent of complex language and recursive thinking – the ability to embed thoughts within thoughts (e.g. “I know that you know…”), which underlies grammar, planning, and self-reflection. Cognitive scientist Michael Corballis and others argue that recursive thought is the linchpin of human consciousness, enabling language, storytelling, and imagining the future 18 19. Notably, the timeline of when language might have become sophisticated often centers around this same window (~50 kya). If language and symbolic culture truly took off then, Darwin’s hunch about language driving our higher faculties gains strong support. Indeed, Darwin surmised that once a “perfect language” was in place, it could sharpen abstract thought and self-awareness as an incidental effect 10. Modern researchers echo that sentiment, effectively proposing that language created a feedback loop – those who could communicate and conceptualize “self” had an edge, and natural selection favored those traits.

Crucially, evolution can work surprisingly fast when a trait confers a big advantage. The human population was small ~50,000 years ago, so even minor cognitive improvements could spread rapidly through succeeding generations. Scientists examining our genomes today have found evidence that many genes related to brain development and cognition underwent intense selection in the last 50,000 years 6. For example, one study of the human X chromosome found “extraordinary” signals of recent selection, with many of the affected genes linked to neural functions 20. In plain terms, something was driving rapid changes in our brain wiring or chemistry during the Upper Paleolithic – exactly when culture blossomed.

Another clue comes from the realm of culture itself. Anthropologists have documented ancient myths and oral traditions around the world, and some appear to be extremely old—possibly tens of thousands of years old, passed down through uncounted generations. Strikingly, many cultures share similar creation stories about a time before humans were fully human. For instance, Aboriginal Australians speak of a Dreamtime when people lacked certain things until ancestral spirits gave them language and ritual, bringing time and society into being 21 22. Aztec legends tell of a prior race of man “made of wood” who had no souls, no speech, no calendars or religion, and only after a great flood did true humans (with those gifts) emerge 21 23. And of course, the Book of Genesis famously depicts Adam and Eve living in innocent ignorance until they eat the fruit of knowledge and become self-aware—“their eyes were opened” and they recognized their naked selves 24. These myths, though varied, echo a concept that humanity had a childhood: a phase without self-knowledge or culture, which was ended by some transformative event (often portrayed as divine intervention or trickery).

Evolutionary thinkers today take such parallel myths as potential “fossil stories”—they might encode memories of real psychological shifts in our distant past 22. It’s speculative, but intriguing: if a dramatic transition to consciousness occurred, perhaps early humans mythologized it, and those narratives survived. Darwin, who collected data on everything from finch beaks to facial expressions, would not dismiss such cross-cultural evidence out of hand. He might not fully trust myth as data, but he would note the pattern: wherever you go, people have ancient tales of becoming self-aware, gaining language, and leaving an Edenic state 25 26. This broad concurrence hints that something real and significant might underlie the lore.

In summary, modern science and scholarship have sketched a scenario Darwin didn’t have access to: an evolutionary turning point roughly 50,000 years ago when Homo sapiens – already physically modern – underwent a mental and cultural awakening. Evolutionary theory needs to account for this relatively sudden change, and that’s where the Eve Theory of Consciousness comes in. It’s a bold hypothesis that attempts to connect all these dots – evolution, genetics, archaeology, and mythology – into a cohesive story of how we got our souls.

| Aspect | Darwin’s 19th-Century View | Current Understanding (21st-Century) |

|---|---|---|

| Timeline of human behavior | Gradual development over eons; no clear line between ape and human 8. | Evidence shows a rapid cultural explosion |

| Origin of self-awareness | Mysterious; likely evolved incrementally via higher intellect and language 10. Admitted the exact origin was unresolved [^oai1]. | Hypothesized to emerge relatively late with advanced language and culture – a “big bang” of mind in the Upper Paleolithic 27 17#:~:text=50%2C000%20years%20ago%2C%20began%20spreading,1). |

| Mechanism of change | Natural selection acting on mental faculties (no supernatural help); analogy to child development and animal instincts 11 28. | Natural selection and cultural feedback driving rapid brain evolution; possibly triggered by a genetic mutation or environmental catalyst (e.g. symbolic communication) 17#:~:text=50%2C000%20years%20ago%2C%20began%20spreading,1) 6. |

| Role of the sexes | Emphasized male competition & female choice in evolution; did not specifically credit women in mental evolution (Victorian norms) 28. | Growing evidence of female-led innovation: EToC suggests women were pioneers of introspective thought, as hinted by mythic matriarchies and sex-linked genetic data 29 4. |

The Eve Theory of Consciousness: How Humans “Evolved a Soul”#

The Eve Theory of Consciousness (EToC) is a recent proposal by writer Andrew Cutler that tackles Darwin’s unsolved question head-on: how did the human soul—that inner voice of “I”—evolve? The name evokes the biblical Eve not for a literal religious reason, but as a metaphor and mnemonic for the theory’s core idea. In essence, EToC posits that women were the first to achieve self-consciousness, and they subsequently spread this cognitive revolution to men through teaching and ritual. Cutler frames this as an evolutionary “Eve” scenario, where the mothers of humanity gave birth not just to children, but to the very concept of the self-aware mind 2.

According to EToC, for tens of millennia Homo sapiens were anatomically human but psychologically more akin to “noble automatons”—to borrow a phrase from Julian Jaynes, who famously theorized a late origin of consciousness30. They likely lived in the present, guided by instincts, simple communication, and perhaps hallucinated commands (as Jaynes suggested for the Bronze Age mind). But at some point (around 50 kya), some individuals “woke up” internally. Cutler argues these would have been disproportionately female, partly due to biological and social factors. Women, as gatherers and primary caregivers in prehistoric societies, might have been under unique pressures to develop nuanced social understanding (theory of mind) and symbolic communication (to nurture and teach offspring). Intriguingly, modern neuroscience hints at sex differences in the very brain networks tied to social cognition and introspection 31 32. The sex chromosomes themselves affect brain development: studies show they disproportionately influence cortical areas involved in social-emotional processing 31 32. In fact, a genetic analysis found that the X chromosome (of which women have two copies) underwent intense selection in our recent evolution, with many selected genes related to neural plasticity and cognition 6. One such gene, TENM1, crucial for brain connectivity and learning, stood out as highly selected—and fascinatingly, it interacts with snake venom components in neurochemical pathways 33. This peculiar link between a “brain gene” and snake venom becomes important in EToC’s narrative of how consciousness might have been catalyzed.

Eve and the Serpent (artist unknown, 1803). The Eve Theory uses the biblical story as an allegory: a woman, a serpent, and forbidden knowledge. In Cutler’s hypothesis, women’s insight was the “forbidden fruit,” and snake venom may have been the tool to attain it 2 34. He speculates that some resourceful women of the Paleolithic era could have discovered that small doses of certain snake venoms induce altered states of consciousness—visions, intense introspection, perhaps a sense of ego death followed by rebirth as an individual “I”. In cultures worldwide, serpents have long been symbols of hidden wisdom, transformation, and the bridge between life and death. It’s no coincidence, EToC suggests, that a snake tempts Eve in Genesis with the knowledge of good and evil 24, or that in Mesoamerican myth a plumed serpent imparted knowledge to humanity, or that in Greece legends spoke of initiates using potions (possibly venom-derived) in mystery rites. If our distant ancestors experimented with natural psychotropic substances—venoms, hallucinogenic plants, mushrooms—they might have occasionally pierced the veil of ordinary perception and encountered something akin to a “soul experience.” A small community of women, perhaps acting as shamans or wise figures, could have ritualized this process: using controlled venom doses or other means to reach a self-reflective mental state and then guiding others (men) through the same awakening 2 34.

Though this sounds fantastical, EToC marshals evidence that early “snake cults” may indeed have existed and coincided with the dawn of consciousness. Cutler points to ancient sites and symbols: for instance, a 70,000-year-old rock in Botswana carved in the shape of a python, near which artifacts suggest ritual activity; or the prevalence of snake motifs in creation myths across Africa, Australia, and the Americas. If a psychedelic snake ritual was humanity’s first spiritual practice, it might be dimly recorded in our oldest stories. The theory even nods to the controversial “Stoned Ape” hypothesis of Terrence McKenna, which proposed that psychedelics (like magic mushrooms) spurred human cognitive evolution in Africa30. By giving that idea “fangs,” EToC suggests snake venom could have been another such catalyst, possibly more potent or culturally accessible than mushrooms in some regions 35.

From an evolutionary standpoint, what matters is that once a few humans achieved a higher level of consciousness and inner speech, this trait could spread both memetically (taught via language, ritual initiation) and genetically (favored by natural selection). EToC’s mechanism is Darwinian: even a slight increase in recursive thinking ability – the capacity to reflect and model the world symbolically – would confer survival and reproductive advantages. Those who could plan further ahead, communicate complex ideas, or form cohesive groups through shared myths and rituals would leave more offspring 3 27. “Who was having more kids then? Those who were marginally better at recursion,” Cutler writes 3. Over thousands of years (a blink in evolutionary time), these advantages could rapidly drive the fixation of pro-consciousness genes in the population. The archaeological record indeed shows that once modern human behavior appeared, it spread and displaced other human species with startling speed 36 37. Homo sapiens with full cognitive toolkit overwhelmed the Neanderthals and other contemporaries by 40kya 37. Darwin would recognize this as natural selection in action, accelerated by the feedback between culture and biology.

Perhaps the most fascinating support for EToC comes from comparative anthropology and mythology. If women were the first “teachers” of the soul, could echoes of that remain in global folklore? Remarkably, many traditional societies have legends that men stole the secrets of ritual and spirituality from women. For example, an Australian Aboriginal story (recorded in the early 20th century) tells how all the sacred ceremonies originally “belonged to the women,” who used them for childbirth and coming-of-age; men had none of it and “were doing nothing” until they conspired to take over the rituals 4 38. The tale explicitly admits that really the business of sacred knowledge is women’s, and men just hide that fact. Similarly, in Amazonian and Melanesian myths there are recurring themes of a primordial matriarchy where women held the ritual power, later usurped by men – often involving a stolen sacred object (flutes, stones, etc.) or knowledge that gave men dominance. A comprehensive survey by folklorist Yuri Berezkin found this motif (women as original owners of sacred knowledge now forbidden to them) in 85 cultures across six continents 5. Such breadth suggests the story’s roots could go back to the very deep past, perhaps to the first cultures of Homo sapiens. Even Greek myth preserves an echo: the Legend of Athena tells that Athens was first named for a goddess and women had voting power, until men stripped that away and forbade women from voting thereafter 39 40 – hinting that at some earlier time, women’s authority was recognized and later suppressed. Victorian-era anthropologists like J.J. Bachofen noticed these patterns as early as 1861, proposing that the “genesis of culture was rooted in the mother-child relationship” and that prehistoric society may have been matriarchal 41 42. (Bachofen’s ideas were speculative, but it’s noteworthy that even in Darwin’s time some scholars intuited a special role of women in early human development.)

For Darwin, who was skeptical of unscientific extrapolation, the Eve Theory would still need to pass the test of evidence. But consider what we have now that he didn’t: global genetic data, rich archaeological timelines, and thousands of catalogued myths. All three independently point to a pivotal era in human evolution that involved new ways of thinking, and intriguingly, many point to women and perhaps chemical aids (psychedelics) as catalysts. While EToC is not yet a mainstream consensus, it is a compelling synthesis of diverse threads. It essentially tells a scientific creation story: How humans evolved a soul (as the subtitle of Cutler’s essay puts it). Darwin, ever the naturalist, might not be fully convinced without more proof – he’d want to see, for instance, more fossil brain data or experimental evidence on how venom neurochemistry affects cognition. But he would surely be captivated by the attempt to explain, in evolutionary terms, what makes us human in the deepest sense. After all, Darwin devoted his life to showing that even the most complex forms of life have material origins. EToC extends that principle to the origin of our inner life.

Before imagining Darwin’s personal reaction, let’s briefly recap the key features of EToC and how it dovetails with Darwinian evolution:

- Timeline Alignment: EToC zeroes in on ~50kya as the dawn of full consciousness 1, which matches the mysterious cultural “leap” scientists observe. Darwin didn’t know this timeline, but it addresses the gap he might have wondered about between Homo sapiens’ physical and mental development.

- Natural Mechanism: The theory invokes natural selection on incremental improvements in recursion and communication 3 43. This is classic Darwinism – no need for supernatural intervention (which Darwin’s colleague Wallace invoked and Darwin rejected15). The “Eve” hypothesis stays within evolutionary biology, just highlighting sexual selection and social environment as factors.

- Testable Clues: It points to concrete evidence we can investigate: genetic markers on X/Y chromosomes 6 29, cross-cultural myth databases 5, archaeological residues of rituals. Darwin would appreciate that EToC doesn’t just spin a story; it invites scrutiny and attempts falsification (Cutler explicitly calls for his theory to be critiqued scientifically 7).

- Interdisciplinary Synthesis: Darwin was a synthesis thinker – he drew on biology, geology, animal breeding, and more. EToC similarly weaves multiple disciplines. It takes evolutionary theory (Darwin’s domain) and enriches it with insights from psychology, anthropology, and mythology. This broad approach might remind Darwin of how he once integrated observations of pigeons, barnacles, and fossils to argue for natural selection. He’d likely admire the intellectual bravery of trying to connect ancient spiritual narratives with evolutionary science.

With these points in mind, let’s step back and imagine: If Charles Darwin could read about the Eve Theory of Consciousness today, what would he find compelling, and how might he respond?

Darwin’s Hypothetical Reaction: Victorian Wisdom Meets Modern Theory#

Profound Fascination and Curious Delight: Darwin would almost certainly be captivated by EToC’s central premise—that the emergence of the human “soul” can be explained as a natural event in prehistory. He had lamented that the origin of our mental powers was a near-impenetrable mystery [^oai1]; seeing a 21st-century researcher boldly tackle it with evidence would please him immensely. The idea that consciousness arose via sexual selection and social cooperation (with women in the lead) might initially surprise him, but he would find it a clever extension of his own theories. Darwin knew well the power of female choice and maternal care in shaping species. Learning that scientists now suspect women could have driven a cognitive revolution would strike him as plausible and rather poetic. He would be intrigued that EToC identifies a specific window in time and mechanism—something he lacked—and would eagerly examine the data on artifacts and genes that underscore a late blooming of the mind 1 6.

Appreciation of Natural Selection at Work: Darwin would especially appreciate how EToC reinforces natural selection’s role in human evolution. In his later years, he faced critics (and friends like Wallace) who doubted natural selection could account for the mind’s grandeur 28. EToC’s narrative – that even consciousness, our highest endowment, was molded by survival and reproduction advantages – would bolster Darwin’s confidence that his framework was correct. He’d likely nod in agreement reading that those with better recursive thinking had more offspring and spread their genes 3, an elegant Darwinian explanation for why mental complexity accelerated. The emphasis on gradual improvements (from “barely recursive” thought to full self-awareness 43) would resonate with his belief in small steps over time. Darwin might quibble about any implication of an abrupt “big bang” – he’d prefer to see it as a rapid yet still incremental series of adaptations 8. But fundamentally, he would find it compelling that the theory connects the dots from genetic mutations to brain function to cultural success in an evolutionary chain. It’s a satisfying answer to how a rational material process could yield something as seemingly immaterial as the sense of self.

Surprise at the Power of Myth and Culture: One aspect that would likely astonish Darwin is the role of mythology and cultural memory in scientific hypothesis. Victorian science in Darwin’s day gave little credence to folklore as evidence. However, Darwin was not unfamiliar with using diverse sources – in his work on emotional expressions, for instance, he gathered observations from missionaries and ancient texts. Upon seeing the global pattern of myths about women’s lost primacy and forbidden knowledge 5 4, Darwin might raise an eyebrow, but also feel a thrill. The sheer consilience of evidence – when Australian Aboriginal stories align with Greek legends and Amazonian tales – would strike him as unlikely to be pure coincidence. He might conjecture, as EToC does, that these widespread stories hint at a real chapter in the human past 22. Darwin, who championed the common descent of all humans (against those who believed in separate creations), would be heartened that mythological commonalities support a single origin of modern human consciousness. He would, of course, maintain scientific caution: he might say, “These echoes of a primeval matriarchy are fascinating, though one must be careful not to confuse story with fact”. Still, he’d acknowledge that such concordance across cultures “ought not to be dismissed, if it aligns with independent scientific indications.” The idea that a scientific theory can draw predictions from myth – for example, EToC predicted that archaeology might find snake-related ritual artifacts, which indeed have been found – would impress Darwin as an innovative approach. It appeals to his sense of nature’s interconnectedness, bridging biology, anthropology, and even the humanities.

Scientific Skepticism and Constructive Critique: Ever the meticulous empiricist, Darwin would not accept EToC uncritically. He would likely praise the theory’s ambition and creativity while also delineating what evidence he’d want to see to be fully convinced. For instance, Darwin might ask: Can we find more direct archaeological evidence of these supposed “venom rituals”? Perhaps cave art of snakes being used in ceremonies, or residue of toxins in ancient gathering sites. He’d also be interested in the genetic angle – he would inquire about how strong the signals of selection on brain-related genes really are, and whether alternative explanations (like interbreeding with now-extinct humans) could account for them. (Notably, the EToC-friendly data on X-chromosome selection 6 is partly tied to archaic admixture with Neanderthals, something Darwin couldn’t know but we now do.) Darwin might also question the gender aspect: Why women first? He’d want to explore whether males could equally have had the spark of insight or whether something like X-linked inheritance of cognitive traits made women the initial beneficiaries (since women have two X chromosomes, a beneficial mutation there could spread faster in females). He would bring up his own observations – for example, that in “savage” societies of his time, women were often tasked with repetitive labor and men with decision-making, reflecting on whether that was a cultural distortion or something with roots in prehistory. If anything, Darwin might gently caution against letting modern sensibilities (or biases) color the interpretation of ancient gender roles. But given that EToC actually sprang from data (mythic and genetic) rather than modern ideology, Darwin would find the matriarchal hypothesis plausible. He knew that mother-infant bonding and teaching is fundamental in all mammals; humans might simply have taken it to another level. In sum, Darwin’s reaction would include healthy skepticism – he’d likely encourage Cutler and others to “critique and test this theory rigorously”, echoing the author’s own call for falsification 7. That means looking for any contradictory evidence (for example, if signs of language or art were found far earlier than 50kya, it might weaken the theory). Darwin would insist that the Eve Theory remain an open hypothesis until more “hard facts” are amassed, a stance any good scientist would share.

Personal Reflection and Enthusiasm: Lastly, one can imagine Darwin’s personal emotional response: a mix of satisfaction and wonder. He might write to a friend that reading about EToC felt like “watching the lights come on” in a dark room he had only dimly explored. Darwin had a lifelong interest in mind, brain, and behavior 44 45 – his study of his own children’s development, his correspondence on animal intelligence, all show he yearned to understand the mind’s evolution. To see the “distant future” he spoke of producing an answer – and one so rich in detail – would delight him. He would be pleased that the solution did not invoke any mysticism but rather extended evolutionary thinking into new territory. In a way, it vindicates Darwin’s hope that even consciousness would eventually be explained naturally. Perhaps he would also feel a touch of whimsy: Darwin, a man who avoided public religious debate, might chuckle at how EToC repurposes religious narratives like Genesis. He would likely admire the poetic symmetry of it – the Bible said a woman and a snake brought knowledge, and now science is saying, in effect, “Yes, something like that might have really happened!” One can almost hear Darwin musing, “How marvelous that the solution to our emergence was hiding in the world’s oldest stories all along, waiting for a scientific mind to decode it.”

In conclusion, Charles Darwin’s reaction to the Eve Theory of Consciousness would probably be one of open-minded intrigue tempered by scientific rigor. He would find it compelling that this modern theory knits together evidence from evolution, genetics, and anthropology to address what he considered one of the great open questions of science 46—what makes us human, and how did it come to be? He would congratulate the effort to “take it seriously” and test it 7, much as he carefully tested his own ideas. And, we can imagine, Darwin would be quietly proud that the intellectual framework he pioneered—evolution through natural causes—has proved capacious enough to encompass even the emergence of the human soul. After reading about EToC, Darwin might tip his hat and say, “We undoubtedly share common ancestors with animals, but at last we have a glimpse of how we became so different.” 47 48

FAQ#

Q1: What is the Eve Theory of Consciousness and how does it relate to Darwin’s ideas?

A: The Eve Theory of Consciousness (EToC) is a hypothesis that human self-awareness (“the soul”) emerged in our species around 50,000 years ago, with women initially attaining and spreading this introspective consciousness; it builds on Darwinian evolution by suggesting natural selection and cultural transmission jointly drove this late cognitive revolution. In essence, EToC extends Darwin’s quest to explain human uniqueness, using modern evidence to argue that even our capacity for inner reflection evolved through survival advantages and social dynamics. 1 2

Q2: Why does EToC propose that women were the first to become conscious?

A: EToC suggests women led the way to consciousness because their social roles (e.g. mothers teaching offspring) and biology (two X chromosomes affecting brain traits) gave them an edge in developing recursive self-awareness, a view supported by cross-cultural myths of women as original keepers of sacred knowledge and genetic signs of recent brain-related selection on the X chromosome 29 5. By this account, once women discovered the concept of “I,” they could teach it to others, kickstarting cultural evolution.

Q3: Did Darwin believe human consciousness evolved gradually or suddenly?

A: Darwin believed that human mental faculties evolved gradually from animal precursors – he wrote that the mental difference between humans and higher animals is one of degree, not kind 9. He speculated that if traits like self-consciousness were unique, they likely arose as by-products of other evolving abilities (especially language) rather than appearing abruptly; however, he admitted science in his time had no clear answer as to when consciousness began in our lineage. 10 [^oai1]

Q4: What evidence supports a “big bang” of human consciousness around 50,000 years ago?

A: Archaeologically, around 50–40 thousand years ago we see an explosion of modern human behaviors – art, complex tools, long-distance trade, and symbolic practices – after hundreds of millennia of little change 1. Genetic studies also reveal extraordinary selection on certain brain-related genes in the last 50,000 years 6. Together, these suggest a rapid evolutionary boost to cognitive abilities (possibly linked to language or social intelligence) during that period, consistent with a sudden intensification of consciousness. 17#:~:text=50%2C000%20years%20ago%2C%20began%20spreading,1)

Q5: How do ancient myths and religions tie into the Eve Theory of Consciousness?

A: EToC posits that some creation myths preserve a cultural memory of the dawn of consciousness – for example, the story of Eve and the serpent symbolizing the first attainment of self-knowledge 2. Myths from diverse cultures often describe early humans lacking selves or souls until some event or knowledge transformed them 21 22. The theory uses these recurring motifs (like women initially possessing forbidden knowledge) as clues, suggesting they echo real prehistoric events – a creative blend of anthropology with evolutionary science.

Footnotes#

Sources#

- Cutler, Andrew. “Eve Theory of Consciousness v3.0.” Vectors of Mind (Substack), Feb 27, 2024. 1 2

- Darwin, Charles. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. London: John Murray, 1871. 9 10

- Smith, C. U. M. “Darwin’s unsolved problem: the place of consciousness in an evolutionary world.” Journal of the History of Neurosciences 19.2 (2010): 105–120. [^oai1] 44

- Klein, Richard G. The Dawn of Human Culture. John Wiley & Sons, 2002. 17#:~:text=50%2C000%20years%20ago%2C%20began%20spreading,1)

- Liester, Mitchell B., and Clark Maxon. “The Stoned Ape Theory Revisited.” Psychology Today, June 1, 2024. 49 50

- Witzel, E. J. Michael. The Origins of the World’s Mythologies. Oxford University Press, 2012. 21 22

- Skov, Laurits, et al. “Extraordinary selection on the human X chromosome associated with archaic admixture.” Cell Genomics 3.3 (2023): 100274. 6 33

- Berezkin, Yuri. “Theme F38: Women were possessors of sacred knowledge now taboo for them.” Database of Eurasian Mythology (collected 2010s). 5 4

- Bachofen, Johann J. Mother Right (Das Mutterrecht), 1861. (Translated excerpts in Myth, Religion, and Mother Right, Princeton University Press, 1973.) 41 39

- Corballis, Michael C. The Recursive Mind: The Origins of Human Language, Thought, and Civilization. Princeton University Press, 2011. 18 19

In 1869, Darwin’s co-discoverer of natural selection, Alfred Russel Wallace, shocked him by suggesting that natural selection alone couldn’t explain the human mind and that a “higher intelligence” must have guided the development of our large brain and consciousness. Darwin vehemently disagreed, maintaining that even our exalted mental powers must have evolved through natural processes 28. The Eve Theory’s insistence on a material, evolutionary origin of consciousness – without supernatural intervention – is something Darwin would have welcomed in rebuttal to Wallace’s spiritualism. ↩︎ ↩︎

[Wikipedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Klein_(paleoanthropologist) ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

The “Stoned Ape Theory,” proposed by ethnobotanist Terence McKenna in 1992, speculates that psychedelic mushrooms ingested by early humans catalyzed leaps in cognition, including language and creativity 49 50. EToC invokes a similar idea of chemical assistance in evolving consciousness – but imagines snake venom in ritual contexts as the mind-altering agent that gave “the knowledge of good and evil” (self-awareness) its first spark 34 35. ↩︎ ↩︎