TL;DR

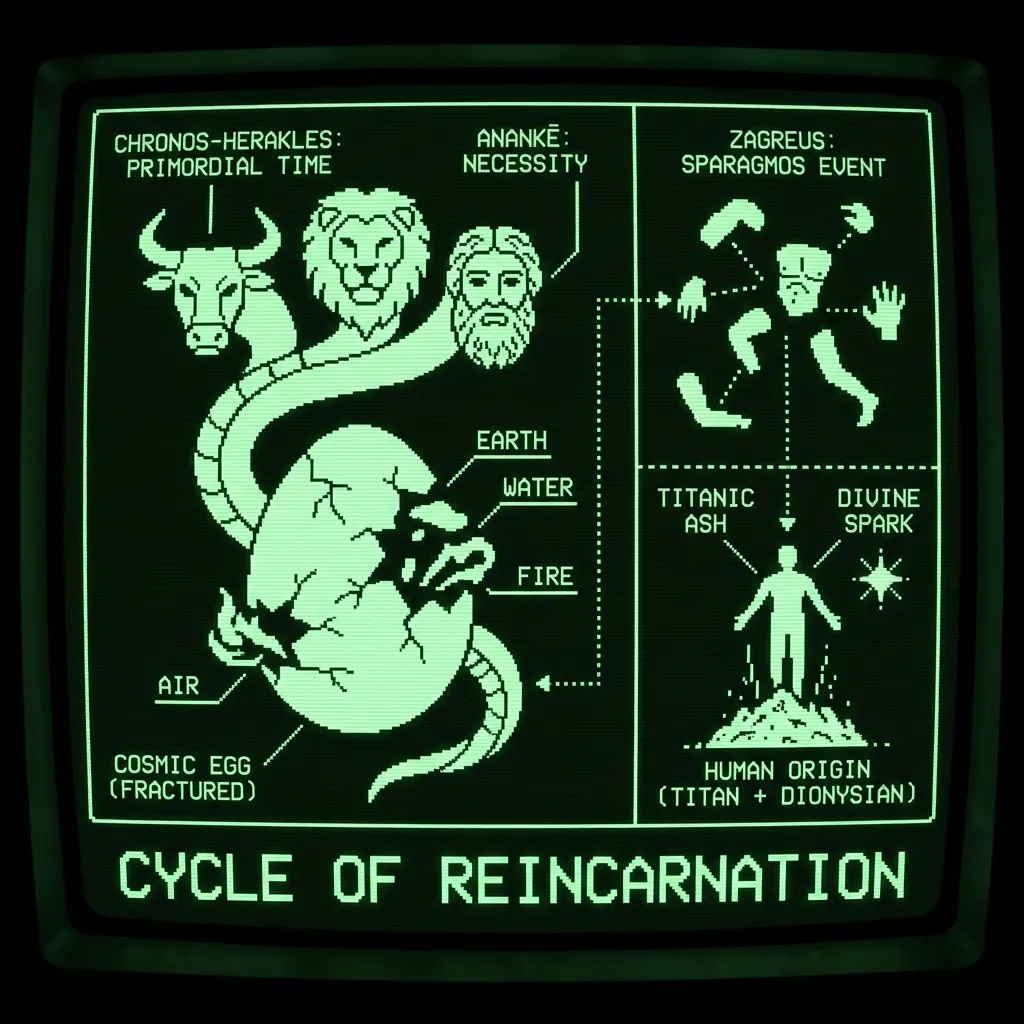

- Cosmic Herakles = Chronos: Orphic myth identifies primordial Time (Chronos) with Herakles, a serpentine creator who binds the cosmos with Necessity (Anankē) and generates the world-egg.

- Dionysus Zagreus = Redeemer: The twice-born son of Zeus (as serpent) and Persephone, whose dismemberment by Titans creates humanity (Titan ash + divine spark) and whose rebirth offers initiates liberation (lysis) from the cycle of reincarnation.

- Complementary Macro/Microcosm: Chronos-Herakles represents the macrocosmic framework of Time and Fate; Dionysus Zagreus represents the microcosmic path to salvation through suffering, rebirth, and mystic union.

- Shared Symbols: Serpents (cosmic binding, divine parentage, rebirth), dismemberment (cosmic creation vs. human origin/fall), katabasis (underworld journey), and the ouroboros (cyclical time vs. escape) link the two figures.

- Ritual & Philosophy: Orphic rites focused on purification and identification with Dionysus. Neoplatonists integrated these myths, viewing Chronos as the principle of emanation and Dionysus as the principle of return (epistrophē).

1 Orphic Cosmogony and the Role of Cosmic Herakles (Chronos)#

In Orphic theology, the origin of the cosmos begins not with the familiar Titans of Hesiod but with a primordial Time-god identified as Chronos (Unaging Time) – a deity the Orphics often merged with Herakles in a cosmic sense. According to Orphic theogonies preserved by later Neoplatonists, in the beginning there existed only Hydros (Water) and Gaia (Earthly matter or Mud), and from their mingling Chronos was engendered. This Chronos is no ordinary personification of time, but a great serpentine being described as having three heads – one of a bull, one of a lion, and a god’s own face in between – with wings upon his shoulders, coiled in the form of a dragon. In the Orphic fragments, it is explicitly said “its name was Chronos… and also Herakles.” In other words, Orphic myth names primordial Time itself as “Herakles,” a figure of immense generative power. United with Chronos-Herakles is the equally primeval force of Anankē (Necessity), also figured as a serpent (sometimes called Adrasteia, the Inevitable) entwined with Chronos. The union of these serpentine powers – envisioned by scholars as two serpents intertwined, an image of the ouroboros or cosmic cycle – represents the binding of the universe by time and necessity. In Orphic hymnody Chronos is even addressed as “ageless” and indestructible, a force that generates all things.

Under the Orphic cosmology (often termed the Hieronyman or Rhapsodic Theogony in modern scholarship), Chronos-Herakles is the first principle in the chain of creation. From Chronos and Anankē’s cosmic embrace were born the fundamental elements: Aither (upper air, bright ether) and Khaos (the gap or chaos of space), as well as Erebos (darkness). In Orphic poetry Chronos is called the “father” of these three primordial offspring. Most significantly, Chronos in Orphic myth fashions the cosmic egg – “great Chronos fashioned the shining egg in the divine Aither” – a silvery or white Orphic Egg that contained the seeds of the universe. Coiling snake-like around this world-egg, Chronos and Anankē applied cosmic pressure until the egg split apart. From the cracked egg emerged the Protogonos (First-Born) – also called Phanēs (the Manifestor of light) or Erikapaios – a divine hermaphroditic figure who would initiate creation in earnest. In some accounts, this First-Born carried the same kind of composite animal features originally borne by Chronos himself (mirroring the bull, lion, serpent imagery), indicating that the Orphics saw the primordial creator as a continuum of forms. Notably, one Orphic fragment reports “the first god bears with himself the heads of many creatures… of a bull, of a serpent, and of a fierce lion, sprung from the primeval egg”, a description applied to Phanēs but often overlapping with the image of Chronos who begat that egg. Essentially, Chronos-Herakles is the macrocosmic generator, the initiator of the Orphic creation cycle and the power that “distributed the world to Gods and mortals” as one text says. After cracking the egg and giving birth to the cosmos, Chronos (Time) and Anankē (Necessity) continue to entwine the universe, encircling the ordered world and driving the rotation of the heavens – an explicit image of Time as a cosmic ouroboros, the serpent-circle that keeps eternity turning.

Importantly, identifying Chronos with Herakles in this context elevates Herakles from the plane of heroic saga to a cosmogonic principle. The name Herakles (meaning “Hera’s glory” or “glorious hero”) is here stripped of its purely legendary connotations and instead attached to the first god. One Neoplatonic commentator explains that “the figure of Chronos (Time)… is called Herakles,” and speculates that the choice of Herakles may relate to allegories of the cosmic cycle. Indeed, Stoic philosophers had long before made similar associations: for example, the Stoic allegorist Cornutus says “Heracles is universal reason thanks to which nature is strong and mighty”, identifying the hero with the logos that sustains the world. Cornutus even notes that the mythic club and lion-skin of Herakles were symbolic “badges” of this god’s cosmic strength. The Stoic Cleanthes (3rd century BC) interpreted Herakles’ Twelve Labors as an allegory of the twelve signs of the Zodiac, i.e. the great cycle of time. All these interpretations align with the Orphic notion of a “Herakles of great power… all-devouring” – epithets that appear in Orphic fragments and which evoke Time’s inexorable strength. In the Orphic theogony, Chronos-Herakles’ “boundless power” is to turn the wheel of time and thus to perpetuate the existence of the cosmos. We find, for instance, Damascius (6th century AD) reporting that “the highest principle in [Orphic] theology was Ageless Time (Chronos)… the serpent Time, also called Herakles”, who initiates the first generation of gods. By naming Time as Herakles, the Orphic tradition made the hero into a timeless All-Father – “the best offspring of Ge (Earth), father of all, the brave Titan who devoured all things”, as one Orphic verse calls him in an apparent equation with Kronos. This Cosmic Herakles is a far cry from the club-wielding son of Zeus in the popular imagination; he is rather a primordial, bisexual serpent-dragon who encompasses the universe. In summary, Chronos-Herakles represents the macrocosm in Orphic cosmology – the great Time-Binder who establishes the cosmic order, generates the first gods, and ensnares the cosmos in the eternal, cyclic flow of time (often symbolized by the serpent biting its own tail).

2 Dionysus Zagreus: Myth of Dismemberment and Soteriological Role#

Counterbalancing Chronos in the Orphic worldview is Dionysus, especially in his mystic form as Zagreus, the “first-born Dionysus” and chthonic son of Zeus. Orphic myth tells that Zeus, in the shape of a serpentine dragon, begot a child upon his daughter Persephone in the secrecy of the underworld. This child was Zagreus, a horned infant deity whom Zeus intended as his heir. In the Orphic Hymns – a collection of devotional poems used by initiates – Dionysus is explicitly celebrated as “Eubouleos, whom the leaves of vines adorn, of Zeus and Persephoneia occultly born in beds ineffable”. From birth, Zagreus-Dionysus thus has a dual nature: he is a subterranean Zeus (sometimes called Zeus chthonios) and the progeny of Persephone, queen of the underworld. This positions Dionysus as a bridge between Olympus and Hades – the microcosmic god who will concern himself with the souls of men and their redemption, in contrast to Chronos-Herakles’ remote cosmic creation.

The central Orphic myth of Dionysus Zagreus is one of suffering, death, and rebirth, laden with symbolic import. Zeus places the infant Zagreus on the throne of heaven, entrusting him with thunderbolts and declaring him his successor. But the Titans – primordial beings resentful or instigated by a jealous Hera – plot against the divine child. In the Orphic account (preserved in various late sources), the Titans distract the child with a mirror and enchanting toys and then savage him with knives, tearing young Dionysus into pieces. The dismemberment (sparagmos) of Dionysus is a core element: “Orpheus has handed down the tradition in the initiatory rites that [Zagreus] was torn in pieces by the Titans.” We find this testimony in Diodorus Siculus and other writers, confirming that the dismemberment of Dionysus was taught in Orphic mystery-rituals as an allegory of profound significance. The Titans devour Dionysus’s flesh raw (omophagia, in some versions, after roasting each portion on spits), a grotesque act that nonetheless has cosmic consequences. Zeus, informed by Athena (who saves the god’s heart), strikes the Titans with his thunderbolt, incinerating them for their crime. From the ashes of the Titans – mixed with the divine flesh they had consumed – arose humankind, according to the Orphic doctrine. This mythical anthropology implies that humans carry a dual nature: the Titanic element (the material, sinful, and lawless aspect, inherited from the evil Titans) and a tiny spark of the Dionysian element (the soul or divine essence, from the god’s flesh). As the late Neoplatonist Olympiodorus succinctly interprets it, “the Titans, having eaten Dionysus, became the progenitors of the human race, which is therefore both guilty (from the Titans) and divine (from Dionysus)”. Orphism thus taught a doctrine of inherited guilt or impurity (often likened to “Original Sin” in modern comparisons ) coupled with an inherent divine potential in each human soul.

Crucially, Dionysus himself is reborn after his murder, and this resurrection underpins his role as a savior. In one Orphic version, Zeus retrieves the infant’s heart from Athena and swallows it, then later sires a new Dionysus by implanting this heart into the womb of Semele (a mortal princess) – thus Dionysus is born again, now as the son of Zeus and Semele (the familiar form of Dionysus worshipped in Greek religion). In another version, Zeus reconstitutes Dionysus from the saved heart, or Apollo gathers the limbs of Zagreus and brings about his rebirth. Either way, Dionysus “was also called Dimetor (of two mothers)… the two Dionysoi were born of one father but of two mothers”. The Orphic theologians were well aware of the two births of Dionysus – one from Persephone in the distant past, one from Semele in the mortal realm – and they fused them into a single sacred narrative of a doubly-born god. Diodorus notes that the younger Dionysus “inherited the deeds of the older” such that later people thought there was only one Dionysus. This merging allowed Orphic practitioners to identify the mystery god Zagreus with the popular Dionysus of Greek cult (son of Semele), unifying the worship. In Orphic myth Dionysus thus becomes Dionysus Bakchus twice-born, torn apart and resurrected, a deity who fully experiences death and rebirth. His epithets “Zagreus” (perhaps meaning “Great Hunter”) and “Bakchos” (Bacchus, often used in the mysteries) often signify this chthonic, suffering aspect. Artists in Late Antiquity sometimes depicted this by giving Dionysus horns (from his infancy as horned Zagreus) or portraying him as an infernal Dionysus seated beside Persephone.

The soteriological role of Dionysus in Orphism cannot be overstated: he is the god through whom the redemption of human souls is effected. Since humans are born from the Titans’ crime, they inherit a kind of miasma (pollution) and are fated to endure a cycle of rebirth (metempsychosis) as a penalty. As the Orphic gold lamellae (thin tablets buried with initiates) repeatedly suggest, Dionysian initiation was believed to offer purification from this Titanic inheritance and a route to break free from the cycle. One gold tablet unearthed at Pelinna in Thessaly addresses the initiate in the voice of an Orphic ritual formula: “Now you have died and now you have been born, thrice-blessed one, on this very day. Say to Persephone that Bakchios (Bacchus) himself set you free. A bull, you rushed to milk… You have wine as your fortunate honor. And rites await you beneath the earth, just as for the other blessed ones.”. This remarkable inscription shows the initiate proclaiming that Dionysus-Bacchus has liberated them – essentially presenting the password to Persephone to secure a favorable lot in the underworld. (The strange images of rushing into milk and becoming a bull or ram likely reflect symbolic rebirth and Dionysian mysticism.) Another tablet from Thurii similarly instructs the soul to declare to the Underworld Queen: “I am a child of Earth and starry Heaven, but my race is heavenly; and this you know yourselves. I have fallen as a kid into milk.” and goes on to say “Bacchus has himself released me”, emphasizing Dionysus’s role as liberator of the soul. Thus, Dionysus is cast as a savior deity who releases the soul from the “wheel of rebirth”. A fragment of Orphic teaching cited by Damascius confirms this function: “You, Dionysos, having power over them (mortals)… whomever you wish you will release from harsh toil and the unending cycle.”. In Orphic belief, the “harsh toil” is life itself, bound in the unending goad of reincarnation – and Dionysus, through his passion, holds the keys to free the virtuous from this fate.

It is important to note that the Orphic Dionysus cult was a mystery cult, meaning its rituals were secret and aimed at a mystical union with the god. The myth of Dionysus’s dismemberment was likely mirrored in Orphic ritual symbolism. Some scholars theorize that Orphic initiates participated in symbolic or actual sparagmos (tearing) of a sacrificial animal (perhaps a bull or goat identified with Dionysus) and the omophagia (eating of raw flesh) as a way to reenact the Titans’ crime and partake of the god’s substance – thus reconstituting Dionysus within themselves. While direct evidence of ritual sparagmos in Orphism is debated, dramatic performances of the myth might have been part of initiation. Literary sources (like the Euripidean portrayal of Dionysian rites in The Bacchae) show Maenads rending animals in Dionysus’s frenzy, which could reflect older mystery practices. Orphic initiates, however, were generally ascetic (renouncing blood sacrifice and certain foods like eggs and beans, according to some ancient testimonies) and focused on purification (katharsis) and sacred ritual meals. The gold tablets indicate that after death the initiate could claim identification “I am Bacchos” – literally becoming one with Dionysus – which signifies that through ritual death-and-rebirth in Dionysian mysteries, the soul assimilated the god’s immortality. One inscribed tablet fragment reads: “Happy and blessed one, you shall be god instead of mortal”, implying that union with Dionysus elevated the initiate to divine status. In sum, Dionysus Zagreus serves as the microcosmic, salvific principle in Orphism: he undergoes death and resurrection to show the way for souls, and by participating in his mysteries (through sacramental experiences and living a pure life), the Orphic initiate seeks to overcome their Titanic nature and realize the Dionysian spark within, achieving ultimate liberation (Greek: lysis).

3 Serpents, Dismemberment, Katabasis, and Ouroboric Time – Symbolism and Complementarity#

On the surface, the figures of Chronos-Herakles and Dionysus-Zagreus might not seem obviously related – one is a serpentine Time-dragon at the dawn of creation, the other a twice-born godsoul who dies at the hands of Titans – yet the Orphic tradition deliberately places them in a complementary relationship, and they share important symbols and themes that bind the macrocosm to the microcosm.

3.1 Serpents#

Serpents are a key symbol linking the two. Chronos as Cosmic Herakles is envisioned as a great serpent encompassing the world, an image of time encircling space. Tellingly, when Zeus impregnates Persephone to engender Dionysus, he does so in the form of a snake (drakon). This detail – Zeus-as-serpent – implies that the essence of Chronos (the serpentine father figure) is carried into the genesis of Dionysus. In a sense, Dionysus is born out of the coiled time-serpent: the Orphics could say that the same primordial force which wrapped the cosmic egg also coiled around Persephone to produce the child savior. In iconography, Dionysus and his followers are often entwined with snakes as well. Vase paintings and reliefs of bacchic rites show maenads handling serpents, and initiates in Bacchic mysteries sometimes wore wreaths of snakes. The snake in Dionysian context can symbolize the god’s chthonic aspect (as snakes dwell in the earth) and rebirth (snakes shed their skin and were associated with renewal). The Ouroboros – the snake biting its tail – perfectly symbolizes Chronos as cyclical time, but it also appears in mystical symbolism as the cycle of death and rebirth that Dionysian initiation hopes to break. Thus, serpents represent both the bondage of the soul in matter (Chronos’s ever-turning wheel) and the power of divinity that can either entrap or liberate. Orphic myth effectively makes Dionysus the son of the great serpent (since Zeus-Drakon fathered him), meaning the microcosmic savior is born from the macrocosmic generator.

3.2 Dismemberment and Reconstitution#

The theme of dismemberment and reconstitution also unites the two figures on a symbolic level. Chronos-Herakles does not suffer dismemberment, but interestingly he does perform a “dismemberment” of sorts on the primordial Egg – splitting it apart to form the ordered universe. This cosmogonic dismemberment is a creative act: by breaking the egg, Chronos releases Phanes (Life and Light) to build the world. Dionysus’s dismemberment by the Titans is its tragic mirror in the human realm: a divine being is broken into pieces, which leads to the formation of the human world (the rise of humans from the Titans’ ashes). In both cases, a unified divine source is broken into multiplicity. Phanēs bursting forth from the shattered egg becomes the manifold cosmos; Dionysus torn apart is diffused into the multitude of human souls. This parallel was noted by Neoplatonic philosophers who loved to find correspondences between macrocosmic and microcosmic events. The Orphic Rhapsodies arranged the myths in a sequence of divine kingships (Protogonos → Night → Ouranos → Kronos (the Titan) → Zeus → Dionysus) such that Dionysus’s brief reign and murder actually capstone the entire cosmogony. In a theological sense, Dionysus recapitulates the creative acts that began with Chronos – but at the level of soul and moral life. The tearing of Dionysus reflects the “tearing” of unity into diversity that the One God had to undergo to make a world of many beings. Therefore, what Chronos-Herakles initiates, Dionysus-Zagreus consummates (and then offers to reverse for the blessed). It is striking that one Orphic hymn calls Dionysus “Protogonos Dionysos,” effectively identifying him with the First-Born creator. Likewise, Orphic texts sometimes merge Chronos with Phanes, or Dionysus with Phanes, showing a fluid identity between the first creator and the last redeemer. The dismemberment of Dionysus also had ritual resonance – as mentioned, Orphic initiates might symbolically consume the god (through wine and offerings) to reintegrate his scattered members within themselves, just as Zeus gathered the heart and limbs of Zagreus to resurrect him. This gives the adherent a personal stake in “putting Dionysus back together,” which is equivalent to restoring the lost wholeness of the soul.

3.3 Katabasis#

Katabasis, the motif of descent to the underworld, ties into both Chronos’s domain and Dionysus’s. Chronos’s partner Anankē is said to stretch her arms “through the universe”, touching its extremities – one can imagine one serpent (Time) spiraling from the heights while the other (Necessity) reaches down into the depths, binding even Hades. Time holds sway in the underworld as much as in the heavens, since the dead await reincarnation. Dionysus, as a chthonic god, is inherently linked to the underworld: Zagreus himself is an underworld name, and in some locales Dionysus was worshipped side by side with Hades (the two sometimes syncretized). One of Dionysus’s epithets, “Eubouleus,” is also an epithet of Hades, hinting at Dionysus’s role as a guide of souls. In myth, after his rebirth Dionysus descends to Hades to retrieve his mother Semele (an echo of Orpheus’s own descent for Eurydice) and brings her up to heaven, renaming her Thyone. This act is symbolic of rescue from the underworld, exactly what Orphic initiates hoped Dionysus would do for them. In Orphic tablets, the deceased addresses Persephone and sometimes identifies with Dionysus (for example, “I have become a Bacchus (Bacchos)”), expecting to live with the gods. Katabasis in a broader sense also refers to the soul’s descent into the body (viewed by Orphics as a kind of death or punishment). The dismemberment by the Titans is an allegory for the soul’s fall into generation – the soul (fragment of Dionysus) is imprisoned in material bodies, scattered through the cycle of lives. Dionysus’s own descent into the Titans (via being eaten) and subsequent restoration is a mythic blueprint for the soul: it will descend (be “dismembered” into the world’s plurality) and, through initiation, can ascend and be made whole (reintegrated with the god).

3.4 Ouroboric Time#

The ouroboric nature of time – endless and cyclic – is affirmed by Chronos-Herakles literally being depicted as a self-sufficient serpent encompassing all. The Orphic texts call him “unceasing, ever-flowing Chronos” and describe how after creation “the couple [Chronos and Anankē] circled the cosmos driving the rotation of the heavens and the eternal passage of time”. This image of the Zodiac-wheel turned by Aion appears in Hellenistic art: for example, mosaics of the god Aion (Time-Eternity) show a youthful figure holding a zodiac circle, often with a serpent wrapped around him or the cosmic orb. Such imagery underscores that Time both creates and devours – an idea also embodied by the myth of Kronos (Cronus) the Titan devouring his children, which Orphics possibly understood as a later echo of Chronos-Time consuming all things. Indeed, Orphic hymnody syncretized Chronos with Kronos, calling him “Chronos the father of all, who devours all things and rears them again”. Here we see Herakles/Chronos as the devourer (much like the snake that swallows its tail), a concept which then resonates with the Titans devouring Dionysus. The Titans, in Orphic allegory, can be seen as agents of Time and Necessity – they enact the entropy and division that Time demands. They tear apart and consume the young god, just as Chronos in his destructive aspect eventually consumes his creations. But Dionysus represents the antidote to the tyranny of cyclical time. He is reborn – thus breaking the one-way power of death – and he offers a way out of the closed loop (ouroboros) of reincarnation. When the initiate proclaims that “Bacchus himself set me free”, it implies release from the “windings” of Chronos. Notably, one Orphic fragment from a commentary on Plato states: “Dionysus is the cause of release (lysis) from the circles of rebirth”. Therefore, Chronos and Dionysus are opposing forces in terms of time: Chronos binds souls into the cycle, Dionysus unbinds and frees them. The Orphic mysteries sought to balance these forces – to harmonize the macrocosm and microcosm – by accepting the rule of Chronos (living within the ordered cosmos) but transcending the limits of Chronos through Dionysian liberation.

4 Orphic Ritual Praxis and Neoplatonic Synthesis#

In practice, Orphic devotees expressed the complementary roles of Cosmic Herakles and Dionysus Zagreus through their rituals and sacred texts, and later Neoplatonic philosophers systematized these myths into a coherent metaphysical hierarchy.

4.1 Orphic Ritual Practice#

Orphic ritual practice was heavily Dionysian. The followers of Orpheus were often an offshoot of Bacchic mystery cult, distinguished by their emphasis on purity and sacred writings (attributed to Orpheus). Initiates, who called themselves Bakchoi (Bacchuses), participated in rituals that reenacted Dionysus’s passion in symbolic form. They observed taboo diets (for instance avoiding eating eggs, beans, or any creature that might house a reincarnated soul) and wore white garments, striving for ritual cleanliness. Initiation likely included ceremonies where sacred mythic narratives were revealed or dramatized – perhaps a nocturnal rite in which the story of Dionysus’s murder and resurrection was told, corresponding to “sacrifices and honors celebrated at night and in secret” for the earlier Dionysus. The Orphic Hymns themselves were invocations used in ritual, and we find hymns not only to Dionysus but also to Protogonos (Phanes), to Night, to Zeus in his various forms, and even to Kronos (the Titan aspect of Chronos). This indicates that Orphic worship did pay homage to the cosmic principles: for example, the Orphic Hymn to Kronos venerates Kronos-Chronos as " father of the cosmos, devourer of time, cruel, impartial, and unconquerable", blending the idea of the harsh Time-god with reverence for his role in cosmic order. Another hymn, to Zeus, actually folds in the Orphic theology: “Zeus was first, Zeus is last: Zeus is the head, Zeus the middle, from Zeus all things are made”, culminating in “Zeus is Dionysus” – a direct identification of the highest with the savior. Through such liturgy, initiates conceptually integrated the rule of Chronos (often via Kronos or Zeus) with the advent of Dionysus. Herakles himself has an Orphic hymn where he is likely praised not just as a hero, but as a cosmic force (unfortunately the Orphic Hymn to Herakles is lost or merged with Zeus’s hymn in some collections). However, given Cornutus’s report that “the hero was deemed worthy of the same name as the god [Herakles] because of his virtue”, we can surmise that Orphic and kindred mystery traditions treated the twelve labors and apotheosis of Herakles as a spiritual allegory – perhaps enacted or referenced in ritual as well (Cleanthes’s interpretation of the labors as zodiacal suggests some ritual calendar correspondence).

In Orphic funerary texts (the gold tablets), the desired end for the mystic is often to join the company of the gods and reign with them. One tablet fragment has the soul declare: “I have escaped from the heavy cycle of grief and rebirth; I have achieved the longed-for crown with swift feet, I have descended into the bosom of the Queen of the Underworld, and I have risen as a holy Bacchus.” In such a statement, the initiate’s soul has taken the same journey as Dionysus – a descent (death or katabasis) followed by a triumphant return (anabasis or rebirth) as a Bacchic godling. This ritual journey is the microcosmic reflection of the great journey of the cosmos: the Orphic cosmos itself emerges, undergoes divisions, and is destined for return (Orphic eschatology hinted at cyclic cosmic renewals, perhaps influenced by Stoic ekpyrosis or by the idea that Zeus, after swallowing Phanes, periodically remakes the world). Notably, the name “Herakles” even appears in certain mystical contexts beyond Orphism – for instance, in the Mithraic mysteries a lion-headed, serpent-wrapped god often identified as Aion Chronos bears the inscription “Leontocephaline Chronos, also called Zeus or Herakles”, showing how widespread the notion of a lion-serpent Herakles as Time had become in esoteric circles. Orphic initiates likely understood that while Chronos/Herakles governs the grand cosmic procession, it is Dionysus who provides the means to transcend it. Thus their rites aimed at aligning with Dionysus – through ecstatic dance, sacred wine (taken not for physical intoxication but as a symbol of spiritual enthusiasm, as Orphics were notably ascetic about wine in daily life), and the singing of Orphic hymns – so that, at the moment of death, the soul could confidently address Chronos’s daughter Persephone and claim freedom from Chronos’s endless loop.

4.2 Neoplatonic Synthesis#

When we turn to the Neoplatonic philosophers of late antiquity (4th–6th centuries AD), we find a sophisticated integration of Orphic mythology into a metaphysical framework. Philosophers like Proclus and Damascius took the Orphic revelations as containing deep truths about the structure of reality, which they mapped onto the Platonic system of emanations. Proclus famously stated: “All that the Greeks have handed down about theology is the progeny of the mystic lore of Orpheus”, indicating the high esteem in which Orphic wisdom was held. In Neoplatonic cosmology, there is a series of hypostases or levels: the Ineffable One, the procession of Intelligible Gods, the Intelligible-Intellectual Gods, the Celestial Gods, etc. The Orphic Chronos and Phanes were equated with the Intelligible principles at the dawn of manifestation. Damascius, in his Problems and Solutions Concerning First Principles, discusses the Orphic theogony at length to illustrate the emanation of reality from the One. He interprets Chronos as the first “principle of wholes” – effectively the eternal One-Life that Neoplatonists call the Nous or the monadic intellect. Chronos (with Anankē) constitutes for him a kind of first Dyad after the One, generating the triad of Being-Life-Intellect symbolized by Aither, Chaos, and the egg/Phanes. Intriguingly, Damascius explicitly notes the Orphic view of Chronos as a bisexual double: a “figure of Chronos/Heracles united with Necessity/Adrasteia… two serpents intertwined… representing the axis of the cosmos”. This he aligns with the “father” principle of the intelligible triad (Zeus, in Plato’s Timaeus, similarly represents the demiurgic father). In Neoplatonic terms, then, Herakles Chronos is a symbol of the enduring unity (male-female) that gives rise to Being – essentially a mythic way to describe the eternal coupling of the active and passive principles in the first emanation.

Dionysus, on the other hand, was associated by Neoplatonists with the “Intellectual Gods” and the process of return. Plotinus, earlier, had used Dionysus’s fate as an allegory for the fragmentation of the Divine Mind into individual souls: “The Intellectual-Principle in its multiplicity is like the dismemberment of Dionysus by the Titans”, he hints in the Enneads. Proclus and others identify Dionysus with Zeus’s intellect or the “Noeric Zeus”, since in Orphic myth Zeus swallows Phanes (the prior creator) and incorporates the entire cosmos in himself, then begets Dionysus as his successor. In this reading, Dionysus becomes the manifest god of the third procession – the god who in himself contains the multiplicity of life (hence his myth of being torn to pieces, which is the dispersion of the Nous into souls). Proclus, in his Platonic Theology, lists Dionysus among the encosmic deities who aid the regress of souls. He sees the “Zagreus” aspect as Dionysus’s intelligible function (Dionysus as the Lord of the vivifying triad, associated with Persephone and the lower world), and the Dionysus (proper) as the son of Semele as the encosmic god who wanders the earth. Importantly, Proclus notes that “Dionysus is a god who frees and purifies souls”, calling him Lysios (Releaser). In one fragment, Proclus or Damascius explains that Dionysus “was entrusted with the keys of the cosmos” by Zeus, meaning he has the authority to open the gates for soul’s ascent (an authority ritually invoked by initiates). Neoplatonists thus fit Dionysus into their schema as the god of liberation at the level of the sub-lunar and psychic realms – effectively in charge of the way up. They also loved the symbolism of Dionysus’s double birth and dual mother as reflecting the dual nature of reality (intelligible and sensible). Diodorus’s mention that Dionysus was called Dimētōr (of two mothers) because the two Dionysoi had one father (Zeus) was interpreted to mean the Intelligible Dionysus and the perceptible Dionysus are one in essence.

Philosophers like Olympiodorus (6th century) gave allegorical commentary on the Orphic myth in their lectures on Plato. In his commentary on the Phaedo, Olympiodorus lays out that the Titans who kill Dionysus represent the passions and vices that rend the unified soul, and the sparagmos of Dionysus symbolizes the soul’s incarnation into the many human bodies. The purification and reassembly of Dionysus corresponds to philosophy and initiation saving the soul from dispersion. Olympiodorus explicitly equates the Titans’ punishment and human creation with the need for humans to atone for that Titanic inheritance, exactly echoing Orphic doctrine. Proclus, in his commentary on Plato’s Cratylus, discusses the name “Dionysus” and links it with “διανοία” (thought or intellect) and “σύνεσις” (understanding), again connecting Dionysus to the intellective principle that gets divided and needs reintegration. Thus, within Neoplatonism, Chronos (Herakles) and Dionysus stand as bookends of the emanative cycle: Chronos at the start (the procession of the Many from the One), Dionysus at the end (the return of the Many to the One). The mystic cult and the metaphysics reinforce each other – the myths provided colorful narratives for abstract principles, and the rituals provided experiential paths to realize those principles in the soul’s journey.

5 Cosmic Origin and Personal Liberation: A Dual Answer to the Human Condition#

The Orphic pairing of Cosmic Herakles and Dionysus Zagreus addresses two fundamental aspects of the human condition: our origin and our destiny. Herakles/Chronos addresses the cosmic origin – he is the great ancestor, paternal Time, by whose toil (his “Labors” in an allegorical sense) the universe is generated and sustained. In him lie answers to “Where did the world come from? What forces govern it?” The answer is a mythical yet philosophical one: from an eternal, self-grown power (Chronos) in conjunction with unyielding necessity (Anankē), through a process of cosmic sacrifice (the breaking of the egg), came all of nature. Human beings, in this vast timeline, are children of Time – subject to Fate, bound by the turning vault of heaven that Chronos powers. This could lead to a rather fatalistic worldview (we are born from the sins of the Titans, condemned to toil and die in endless cycles – a grim prospect). That is where Dionysus balances the scale by addressing personal liberation and hope – essentially answering “How can I be saved? How do I find my true self and eternal bliss?” In Dionysus, the Orphic myth provides a redemptive principle: a god who suffers as we suffer, dies as we die, and yet rises again, blazing a trail that humans can follow. Dionysus’s narrative spoke deeply to the initiates’ psyche: it suggested that even amid the terrors of mortality (dismemberment, death), there is the promise of rebirth and reunion (symbolized by the stitching together of Dionysus’s limbs and his second birth).

For the Orphic initiate, Herakles and Dionysus functioned as complementary forces guiding the soul. Herakles (in his celestial, “astral” form as Chronos) was a reminder of the order of the universe – the law that must be respected. Just as the mortal Herakles had to complete his twelve labors to attain godhood, so the soul must labor through virtue and piety under the auspices of Chronos’s world to earn its reward. Dionysus was the mystical secret that the labors are not in vain – that at the end of the cycle, there is an ecstatic union and eternal life. In a cultural sense, Orphism offered an alternative or supplementary religious experience to the traditional Olympian worship. The Orphic Dionysus was gentler and more personal than the public Dionysian festivals; wine in Orphism became a sacrament rather than a drink, and Herakles was not merely a heroic figure to admire but a cosmic power to be ultimately transcended.

Ancient writers often commented on this duality of Orphic religion. Plato, in the Laws, mentions how the followers of Orpheus live in a manner “contrary to the ordinary” by abstaining from meat (since they believed in the kinship of all living souls due to transmigration) and how they hold a “mystic doctrine” of rewards in Hades. Pindar poetically refers to the fate of souls, saying that those who persevere thrice in keeping their souls pure (probably alluding to Orphic initiations) “will travel the road of Zeus to the tower of Kronos (i.e., Elysium)… and live in the Isles of the Blessed, ruler of a holy kingdom”. This “tower of Kronos” in Elysium is an interesting image – it suggests that even in paradise Kronos/Chronos has a presence (for the righteous, Chronos is not a devourer but a guardian of their afterlife reward). Thus both Chronos and Dionysus reward the pious: Chronos grants the timeless eternity in Elysium, Dionysus grants divine communion. In Orphic belief, these converge.

Finally, the cultural interpretations show Herakles and Dionysus as addressing different psychological needs. Herakles (especially as understood allegorically) represents the rational, law-giving aspect of religion and philosophy: strength, endurance, the mastering of the self (Herakles’s labors can be seen as mastering twelve trials, much as the soul must conquer vice and ignorance). Even in Stoicism, Herakles was a model of the wise man – Cornutus calls him the “giver of strength and power” to the parts of nature. Dionysus, conversely, represents the emotional and spiritual aspect – ecstasy (ek-stasis, standing outside oneself), enthusiasm (having the god en-theos, inside oneself), and ultimate joy beyond the confines of ordinary reason. The Orphic path integrated both: the initiate was expected to be philosophical and pure (following the logic of cosmic justice) and also ecstatic and inspired (following the mysticism of Dionysus). In this way, the Orphic mysteries offered a holistic approach to the human condition: acknowledging that we are children of the cosmos – bound by Time, Fate, and the consequences of a primordial sin – yet also children of God – possessing within us a divine spark that can be rekindled and reunited with its source. Chronos (Cosmic Herakles) and Dionysus (Zagreus) are two ends of a divine thread that spans from the creation of the universe to the salvation of the soul. Orpheus, the legendary founder of these mysteries, was said to have understood both: he sang of the cosmos’s beginning and end, and taught the rites by which men could achieve what the gods ordained. In summary, Cosmic Herakles and Dionysus Zagreus function as complementary forces in Orphic thought – with Herakles as the macrocosmic Time-Lord who sets the stage of existence, and Dionysus as the microcosmic Savior who plays out the drama of death and renewal, inviting humankind to join him in a blessed eternity beyond the circles of the world.

FAQ #

Q 1. What is the core difference between Chronos-Herakles and Dionysus-Zagreus in Orphism? A. Chronos-Herakles represents the macrocosm: the primordial, serpentine god of Time who, with Necessity (Anankē), generates the cosmos, establishes its cyclical laws, and binds it. Dionysus-Zagreus represents the microcosm: the suffering, dismembered, and resurrected god whose myth explains humanity’s dual nature (Titanic/Dionysian) and whose mysteries offer a personal path (lysis) to liberation from the cycle of rebirth governed by Chronos.

Q 2. Why is the dismemberment (sparagmos) of Dionysus so central to Orphic belief? A. The sparagmos serves multiple functions: 1) It explains the origin of humanity from the ashes of the Titans who consumed Dionysus, embedding a divine spark within a flawed nature. 2) It allegorizes the soul’s fall and fragmentation into material existence (incarnation). 3) It provides the mythic basis for Orphic rituals, where initiates might symbolically reenact or contemplate the suffering and reconstitution of the god to achieve purification and unity.

Q 3. How did Neoplatonic philosophers interpret these Orphic myths? A. Neoplatonists like Proclus and Damascius saw Orphic myths as allegories for their metaphysical system of emanation from the One. Chronos-Herakles was mapped onto the highest intelligible principles, representing the initial procession and structuring of Being. Dionysus-Zagreus was associated with the later, intellectual emanations and, crucially, the process of epistrophē (return), symbolizing the Divine Mind’s fragmentation into souls and the path back to unity through purification and liberation (lysis).

Q 4. If Chronos is Time, is he related to Kronos (Saturn), the Titan who devoured his children? A. Yes, ancient sources, including Orphic hymnody, often conflated or deliberately merged Chronos (Time) and Kronos (the Titan son of Ouranos). Orphics likely saw the Kronos myth as a later echo or personification of the all-devouring nature of Chronos (Time). The Orphic Hymn to Kronos addresses him with titles applicable to both, like “father of the cosmos, devourer of time.”

Sources#

- Orphic Fragments and Theogonies (Damascius, De principiis, quoted in West 1983)

- Orphic Hymn 29 (To Persephone) and 30 (To Dionysus)

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4.4–5 and 5.75 (Orphic Dionysus myth and two Dionysoi)

- Gold Orphic tablets from Pelinna and Thurii (as cited by Graf and others)

- Proclus, On the Timaeus and Platonic Theology (comments on Orphic cosmology and theology)

- Cornutus, Compendium of Greek Theology (Stoic allegory of Herakles and Dionysus)

- Cleanthes (via Cornutus) and the Stoics on Herakles’s cosmological symbolism

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca (echoes of the Zagreus story in late epic)

- Pausanias 8.37 and 7.19 (local legends of Dionysus’s travails with Titans)

- Pindar, fr. 133 (Plato, Meno, 81b-c: Pindar on Persephone’s reward to souls)

- Plato, Laws 782c and Cratylus 400c (references to Orphic life and Dionysus’s name meaning).

- Olympiodorus, Commentary on the Phaedo (interpreting Dionysus and the Titans allegorically)

- Plotinus, Enneads (on the fragmentation of the divine mind as Dionysus’s dismemberment).

- Clement of Alexandria and Firmicus Maternus (early Christian accounts of the Orphic myth of Dionysus, with the toys and mirror).

- Mithraic iconography of Aion/Chronos (lion-headed serpent figure labeled “Herakles” in inscriptions)

Additional implicit sources may include general scholarly works on Orphism (e.g., Guthrie, West, Graf & Johnston) and Neoplatonism.