TL;DR

- Many thinkers propose consciousness evolved through stages: from primitive embedded awareness to modern reflective mind.

- Common patterns emerge: archaic/magical → mythic/theological → rational/mental → potential integral/spiritual stages.

- Axial Age breakthrough (~800-200 BCE): Multiple civilizations independently developed rational, self-critical consciousness.

- Modern theories include: Hegel’s dialectical spirit, Gebser’s structures, Wilber’s spectrum, Cutler’s recursion revolution.

- Future evolution anticipated: Most theorists envision higher synthesis beyond current mental-rational consciousness.

- Timeline convergence: Paleolithic magical, Neolithic mythic, Axial Age rational, modern analytical, emerging integral.

Evolutionary Models of the History of Consciousness#

Throughout history, many thinkers have proposed that human consciousness (or our collective worldview and mentality) has developed through stages from primitive beginnings to more complex forms. This “evolution of consciousness” is often mapped onto historical epochs – from prehistoric times, through ancient civilizations, up to the modern age, and sometimes into future possibilities. Below is an exhaustive summary of several notable models, each outlining stages in the development of human consciousness, along with, where possible, how these stages correspond to actual historical periods.

Georg Wilhelm F. Hegel – Dialectical Evolution of Spirit#

Hegel (1770–1831) conceived of history as the progressive unfolding of Geist (Spirit or Mind) toward full self-awareness and freedom. In his philosophy of history, human societies advance through dialectical conflicts that ultimately increase the consciousness of freedom. Hegel famously mapped this progress onto world history, distinguishing several major cultural-historical stages:

- Oriental Despotism: In the ancient “Oriental” world, one person (the divine emperor) is free – society accepts only the ruler as truly autonomous. Freedom is thus the privilege of a single authority. Hegel saw these early theocratic empires as having a tyrannical consciousness where the masses lacked any sense of independent selfhood or rights.

- Classical Greece and Rome: In the Greco-Roman epoch, some people are free – namely, the citizens of the city-state or republic. This era introduced a more differentiated consciousness: a contrast between free citizens and slaves, indicating an expanded awareness that certain classes of humans have autonomous personhood.

- Germanic/Christian Europe: In the modern era shaped by Christianity and the rise of European nations, all persons are in principle free – the idea emerges that freedom and dignity belong to every individual as such. (Hegel credited the Christian notion that all souls are equal before God as a spiritual basis for this universalism.) Here, Spirit attains the concept of free individuality, embodied in modern constitutional states and Protestant conscience.

Hegel asserted that in this final stage, the concept of freedom is fully realized as a universal human attribute. Each historical stage isn’t merely an improvement in social conditions but a qualitative deepening of consciousness – from the passive acceptance of fate under a despot to the active self-determination of individuals in a rational society. This dialectical movement is driven by internal contradictions in each stage’s idea of freedom, which lead to its sublation (overcoming and preservation) in a higher stage. In Hegel’s view, history effectively ends when Spirit knows itself fully – a condition he saw reflected in his own modern Christian-European world, which he considered the highest attainment of absolute Spirit (a controversial eurocentric conclusion). Hegel’s model places the pinnacle of consciousness in the modern age, built upon all prior epochs’ contributions.

(Historical mapping: Hegel’s stages roughly correspond to: early river-valley civilizations of the Near East (Oriental despotism), the classical antiquity of Greece and Rome, and the post-Classical/Christian era in Europe up to the 19th century.)

Auguste Comte – Three Stages of Intellectual Evolution#

Auguste Comte (1798–1857), the founder of positivism, proposed the “Law of Three Stages” describing the evolution of human thought and society. According to Comte, humanity’s collective mind progresses through three sequential stages:

- The Theological Stage: In the earliest phase, humans explain phenomena via supernatural agents. People attribute natural events to the will of gods or spirits. This stage ranges from animism and polytheism to monotheism, but in all cases events are explained by divine intervention or “miraculous” forces. (Comte further subdivided this stage into fetishism, polytheism, and monotheism.) The theological mindset dominated prehistoric and ancient societies where myth and religion were the primary frameworks for understanding the world.

- The Metaphysical Stage: In this transitional stage, supernatural personified deities are replaced by abstract principles or essences as explanations. Phenomena are explained by philosophic ideas like “nature,” “faculties,” or “forces” inherent in things (for example, medieval scholastics speaking of essences, or Enlightenment deists invoking abstract Nature and Reason). Metaphysical thinking is essentially an impersonal, abstracted theology – it invokes entities like “Nature” or “Vital force” instead of gods, or posits ultimate causes and essences beyond empirical reach. This stage roughly corresponds to the late classical and medieval period, when philosophy and scholastic theology tried to rationalize or depersonalize earlier religious ideas.

- The Positive (Scientific) Stage: In the final stage, humanity abandons seeking ultimate causes or supernatural explanations and focuses on empirical observation and scientific laws. All phenomena are now understood through science – i.e. by discovering natural laws and facts, and using reason and experiment. This positivist mindset emerged in the modern era (Comte’s own eighteenth–nineteenth century age) and represents maturity of the intellect. Explanations consist of linking facts to general laws, not invoking ontological essences or divine wills. Comte saw this scientific stage as the culmination of mental evolution, where rational empirical inquiry replaces imaginary or abstract explanations.

Comte believed these stages also mirror an individual’s development from childhood to adulthood. In childhood we are prone to fantastical, animistic explanations (theological); in youth we favor abstract speculation (metaphysical); in adulthood we (ideally) attain scientific reasoning. Comte’s model thus places modern positive science as the highest form of thought, superseding the theological naivety of primitive people and the sterile metaphysics of philosophers.

(Historical mapping: Comte’s theological stage encompasses all of antiquity and the Middle Ages (when religious/mythic thinking prevailed). The metaphysical stage roughly spans the Renaissance and Enlightenment (when abstract philosophical ideas replaced strict theology). The positive stage begins with the Scientific Revolution (17th century) and comes into full force by the 19th century with the triumph of empirical science.)

Giambattista Vico – Corsi e Ricorsi (Cyclical Ages of Consciousness)#

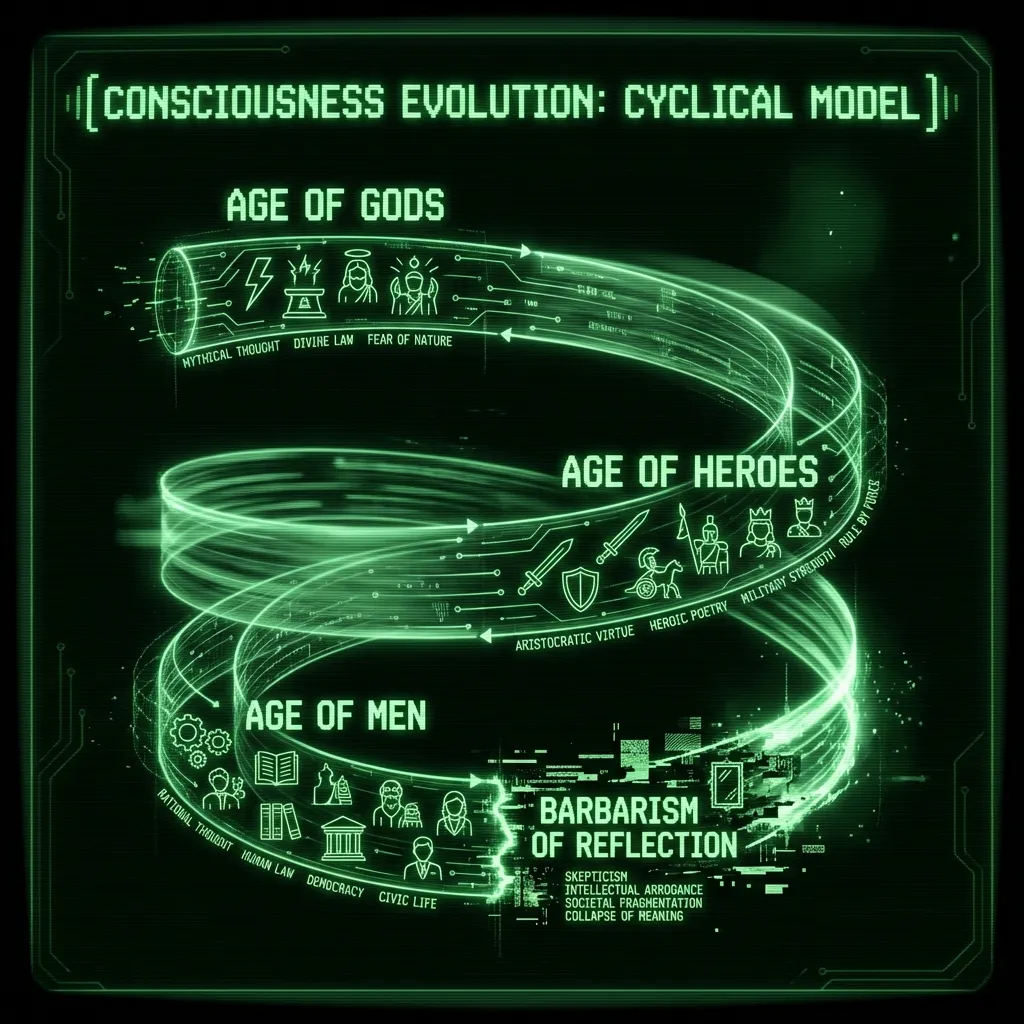

Giambattista Vico (1668–1744), an Italian philosopher-historian, proposed that every nation or culture passes through a cycle of three ages in the development of its collective mentality. In La Scienza Nuova (1725), Vico outlines these stages (followed by a period of decline and a reset, in a repeating cycle), which reflect how human consciousness and society co-evolve:

- Age of Gods: In the beginning, human consciousness is immersed in myth and divinity. The earliest people, lacking abstract reasoning or language, imagine the world in thoroughly mythopoetic terms. Vico theorized that prehistoric humans experienced powerful natural events (like thunderstorms) as the actions of gods – for example, a huge thunderclap was taken as the voice of Jove (Jupiter) speaking. In this stage, everything is attributed to divine beings, and social institutions (like family, marriage, burial rites) are established under religious awe. Human language begins with poetic, imitative sounds (e.g. “Jove!” in fear of thunder) rather than logical categories. Consciousness is thus unitary and imaginative: humans do not yet distinguish between themselves and the natural world’s intentions. They live in a kind of “original participation” (to borrow Barfield’s term) where reality is saturated with gods and signs.

- Age of Heroes: Over time, as societies form, there arises an era of heroic aristocracy. Here consciousness makes a first differentiation: the world is no longer run directly by gods, but by god-like heroic ancestors or demigods. Vico describes this age as one of tribal warlords and patriarchs – e.g. the heroes of Homer or the chiefs of early city-states. Society is hierarchical (nobles vs. commoners), and language and thought are symbolic and metonymic (e.g. heraldic emblems, mythic metaphors) rather than fully abstract. Laws are rooted in sacred tradition and force. The consciousness of this age is still mostly poetic and collective (noble families see themselves as descendants of gods), but nascent ideas of human law and reason start appearing in the interstices of myth.

- Age of Men: Eventually, human society enters an age of common humanity and reason. The heroes are replaced by rational individuals and republics. This stage is marked by the emergence of philosophy, critical reason, and conscious reflection on human affairs. Law becomes secular and universal (the Age of Men sees the development of fully rational law and civic equality – Vico gives the example that in the Roman Republic, law was written and applied to all men, not just dictated by divine-right kings). Language evolves into prose and abstract terms (alphabetic writing appears). Consciousness in this age is markedly self-aware and rational, capable of critique and conceptual thought. Humans now see themselves as human (not half-gods) and begin to pursue secular knowledge. Vico warns, however, that at the end of this stage, rational skepticism and egoism can undermine social unity, leading to a collapse into chaos or “barbarism of reflection,” after which a new cycle may begin.

Vico’s model is cyclical (corsi e ricorsi): after the Age of Men peaks, society may degenerate and a new “barbaric” beginning ensues, which again mythologizes the world (a return to a primitive religiosity). Notably, Vico’s ages correspond to changes in consciousness: from an imagination-dominated mindset (childlike and communal) to an honor-bound, metaphorical mindset (heroic and aristocratic) to a reflective mindset (rational and democratic). These ages can be loosely mapped onto actual history: Vico himself linked the Age of Gods to the early prehistoric and proto-historical period (when religions like those of Egypt or early nomads personified natural forces), the Age of Heroes to the epoch of Homer, the patriarchs, and archaic law (e.g. city-state era, early monarchy), and the Age of Men to the classical republican and modern eras of fully developed civil society. Each nation, he thought, goes through these in its own time. (For example, Vico considered post-medieval Europe to be in an Age of Men, at risk of devolving into a new barbarism if rational liberty lapsed into anarchy.)

19th-Century Evolutionary Anthropology – From “Primitive” Mentality to Modern Mind#

Late 19th-century anthropologists proposed unilinear evolution of human thought, often framing it as a progression from “primitive” to “civilized” modes of thought. These models were not about consciousness in a spiritual sense, but they described the historical development of worldviews and cognitive frameworks:

- Edward B. Tylor (1832–1917): Tylor, often considered the founder of anthropology, argued that the earliest human belief system was animism – the idea that spirits inhabit all things (plants, animals, objects) – which he saw as the root of all religion. Over time, he suggested, animistic beliefs evolved into organized polytheistic religions, and later into monotheism, as cultures became more complex. Ultimately, in modern educated society, scientific reasoning would replace religious explanations altogether. Tylor’s scheme thus implied a mental evolution from a childlike attribution of soul to nature, to belief in many gods, to a more abstract single God, and finally to rational science. (He famously defined culture as “acquired” knowledge and saw “primitive” cultures as living fossils of early stages.)

- James G. Frazer (1854–1941): Frazer expanded on this idea with a three-stage model: Magic → Religion → Science. In The Golden Bough (1890), Frazer posited that early humans used magic as their first way of thinking – essentially a pseudo-science based on erroneous association (e.g. believing that one can influence nature through rituals or symbols). When magic failed to deliver control over the world, humans turned to religion, supplicating gods for aid and order. Later, with the Enlightenment, scientific thought emerged, which for Frazer was the final stage where humans rely on empirical laws and reject both magical manipulation and religious invocation. Frazer thus saw a continuous upward development in rationality: from the pre-logical “technology” of magic, through the imaginative personifications of religion, to the rational-empirical mode of science. He explicitly emphasized that in the modern scientific stage, people see the world analytically, in terms of natural cause and effect, whereas in the magic stage they saw hidden mystical connections, and in the religious stage they imagined personal deities behind phenomena. (Frazer noted magic and science are alike in seeking practical control, whereas religion is about appeasing wills of gods.) Frazer’s ideas mapped mental evolution onto history: prehistoric tribes and ancient shamans practicing magic, classical and medieval societies dominated by religion, and the modern industrial world embracing scientific causality.

- Lewis H. Morgan (1818–1881): Morgan proposed an influential socio-cultural evolution in Ancient Society (1877), dividing human progress into Savagery → Barbarism → Civilization. Each stage was defined by technological and social advancements (use of fire, bow, pottery in savagery; agriculture, domestication, metalworking in barbarism; writing and state organization in civilization). Implicit in Morgan (and those influenced by him, like early Marxists) is a development of mental capacity alongside material progress. For instance, the “savage” stage (hunter-gatherers) was associated with rudimentary language and animistic thinking; the “barbarian” stage (early agrarian societies) fostered mythic narratives, clan identities, and some pragmatic reasoning; the “civilized” stage (from the invention of writing onward) enabled abstract thought, historical memory, and complex reasoning. Morgan’s framework is more about social evolution, but it carries the notion that human consciousness expands with new means of subsistence and communication. (E.g. the use of writing in the Civilization stage corresponds to a leap in reflective thought – recorded law, philosophy, etc.).

Note: Modern anthropology has critiqued these Victorian models as overly simplistic and ethnocentric. However, their influence can be seen in later theories of consciousness evolution. They established the idea that the mode of thought (mythic, religious, scientific, etc.) is tied to stages of cultural development. Thinkers like Frazer and Tylor explicitly treated “primitive mentality” (animistic, magical, pre-logical) as a predecessor to the more “rational” consciousness of educated modern adults.

(Historical mapping: Tylor’s and Frazer’s “magic” corresponds to the practices of Paleolithic and tribal Neolithic cultures; “religion” corresponds to the organized faiths of agrarian civilizations (Bronze Age through medieval times); “science” is the worldview of the modern industrial age. Morgan’s “savagery” roughly aligns with the Paleolithic and Mesolithic eras of foraging; “barbarism” with the Neolithic through early Iron Age village societies; and “civilization” with literate urban societies from antiquity to now.)

Erich Neumann – Archetypal Stages of Consciousness#

Erich Neumann (1905–1960), a Jungian psychologist, charted the psychological evolution of consciousness in mythological terms. In The Origins and History of Consciousness (1949), Neumann argues that human consciousness emerged out of a primordial unconscious through a series of archetypal stages, much like an individual’s ego arises from the unconscious. He uses symbolism from world myths to delineate this evolution:

- Uroboros (Primal Unity): In the beginning, human psyche was in a state of undifferentiated oneness with nature – symbolized by the uroboros (the snake eating its tail, a symbol of self-contained cyclic unity). In this stage, there is no true ego or self-awareness; subject and object are not distinguished. Neumann likens it to an infant’s consciousness or a deep collective dream-state – early humans experienced the world as “one great organism” and themselves only momentarily as separate beings. Mythologically, this corresponds to paradise myths or the womb of the Great Mother. Prehistorically, we might associate this with the earliest Homo sapiens consciousness (Middle Paleolithic), where behavior was driven by instinct and nature’s rhythms, and any nascent sense of self quickly “drowned” back into the group or environment.

- Great Mother and Separation of World Parents: The next stages involve the dawn of the ego through conflict with the maternal matrix of the unconscious. As Neumann describes, humanity’s evolving consciousness faced the archetype of the Great Mother – representing the enveloping powers of nature and the unconscious. This stage is characterized by matriarchal mythology, fertility cults, and an ambivalent relation to the mother figure (both nourishing and threatening). The separation of the World Parents (Sky and Earth in myth) symbolizes the ego separating from the primal mother and father archetypes, introducing duality. Here we see early mythic themes of creation, where the unity of heaven-earth is torn apart to make room for human world – reflecting a nascent sense of otherness. In terms of cultural evolution, this could correspond to the Upper Paleolithic to Neolithic period, when cave art and early myths appear – humans begin to represent and thereby distance themselves from the surrounding world.

- The Hero’s Journey (Birth of the Ego): At a certain point, consciousness becomes individualized enough to be personified as the Hero in myths. The hero myth, found in many cultures, narrates how a hero emerges from the mother, battles monsters (often dragons or serpents symbolizing the uroboric unconscious), and gains a kingdom or treasure – which symbolically is the establishment of a stable ego consciousness. Neumann sees this as the critical turning point where the ego separates from the unconscious and assumes dominance. The hero slays the dragon (overcomes the tyrannical pull of the Great Mother or primal chaos) and possibly marries a princess (union with the feminine on a higher level, indicating integration). Neumann links this stage with the rise of patriarchal tribal societies and ancient empires, where solar hero gods (Zeus, Marduk, etc.) slay primordial monsters and establish order. It’s the era when mythic consciousness (the world of gods, legends, moral dualism) is in full bloom – roughly the Bronze Age cultures with epic narratives like Gilgamesh, the Ramayana, etc. Psychologically, humanity now has a clear ego that can reflect, decide, and struggle with impulses.

- Ego/Self Integration: Neumann’s later stages (implied in his work) involve the ego’s further development and eventual integration with the Self (total psyche). After the hero’s victories, there often comes the “night sea journey” or descent into the underworld – myths of death and rebirth – which correspond to the ego confronting the shadow and deeper unconscious contents. In historical terms, this could correlate with the Axial Age (800–200 BCE) and beyond, when reflexive self-criticism, second-order thinking, and mystical philosophies arose (e.g. Greek tragedy and philosophy questioning the heroism of heroes, Indian and Buddhist introspective practices, etc.). Ultimately, Neumann (being a Jungian) envisioned a possible reunification of conscious and unconscious at a higher level – analogous to Jung’s idea of the Self or a new creative era.

Neumann’s key contribution is seeing the universal mythological motifs as reflections of stages in the evolution of human consciousness. Early humanity’s psyche was maternal, participatory, and unconscious; then came the rise of the individual ego (the hero) and the patriarchal gods, and finally modern self-aware ego capable of introspection (with attendant problems of alienation, which myths of the hero’s death address). He also famously asserted that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny in this context: each individual’s psyche develops through these same archetypal stages (we each have our “uroboric” infancy, our struggle for autonomy, etc.). Thus, studying ancient myths is like seeing the childhood of humanity’s mind.

(Historical mapping: Neumann’s model is archetypal and not tied to specific dates, but one can roughly align the uroboric stage with the Paleolithic hunter-gatherer period (when humans lived embedded in nature with minimal self/other distinction). The Great Mother and early hero myths would span the Neolithic to early Bronze Age (fertility cults, mother goddesses, then warrior storm-gods slaying chaos monsters as in Mesopotamian myth). The full hero/ego stage corresponds to the Bronze and Iron Age civilizations with their pantheons of differentiated gods and legendary heroes (e.g. Hercules, Rama), reflecting a strong but still mythic ego. The later reflective stage aligns with the Axial Age and classical antiquity – when for example Greek philosophers or Buddhist monks question the nature of self and ethics, indicating a consciousness starting to reflect on itself.)

Owen Barfield – Original Participation to Onlooker Consciousness (and Beyond)#

Owen Barfield (1898–1997), a philosopher and linguist, described the evolution of consciousness primarily through changes in language and perception. Barfield argued that ancient humans did not experience the world as modern humans do; instead, they lived in a state of “original participation,” which only later gave way to our current “onlooker consciousness.” Eventually, he foresaw the possibility of “final participation,” a future stage uniting the two. The stages can be outlined as follows:

- Original Participation: This is the mode of consciousness of ancient and prehistoric peoples, wherein individuals felt deeply embedded in the world and intrinsically connected to nature. In original participation, there is no clear sense of an isolated “I” opposite the world; instead, self and world interpenetrate. For example, Barfield notes ancient languages used single words (like Greek pneuma) which meant spirit, wind, and breath all at once, indicating that people experienced those as one phenomenological reality. A person in original participation doesn’t objectify nature – the wind moving the trees and the breath moving one’s lungs were felt as the same living agency. Mythologically, this consciousness corresponds to animistic and polytheistic worldviews where everything is ensouled and signs/symbols are part of reality. (Barfield often cites how for ancient man, language was poetic and literal simultaneously – e.g. saying “Spirit” and “Wind” with one word, meaning both.) This stage persisted through tribal society and early civilizations. In terms of timeline, original participation would span from the dawn of Homo sapiens (Upper Paleolithic) through at least the Bronze Age and even into the early first millennium BCE for many cultures. (Barfield acknowledges that different cultures left this state at different times – e.g. Greek and Hebrew minds began to shift in the first millennium BCE, whereas some indigenous peoples preserved original participation much later.)

- Onlooker Consciousness: This is Barfield’s term for the modern mindset, which arose gradually but came to dominate by the Scientific Revolution (~17th century). Onlooker consciousness is characterized by a sharp subject–object divide: the individual perceives themselves as a “mind” observing a mechanical, external world. Nature is now “out there,” disenchanted and composed of mere things, while meaning is seen as solely in the human mind. This mode was prefigured by the Axial Age and classical philosophers who “stepped back” from participation to reflect on the cosmos (Barfield notes Greek philosophy and Hebrew monotheism already moved toward abstraction, transcending immediate participation). However, it fully materialized in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, with developments like nominalism (e.g. Ockham) and the Copernican worldview, and culminated in Descartes’s dualism (“I think, therefore I am”) and the Newtonian mechanistic science. By the modern period, the world was viewed as objectively devoid of mind or spirit, and humanity as an observer separate from nature. Barfield calls it “onlooker” because we stand apart and look on the world, rather than participating in it. The consciousness of this stage is highly self-aware and analytical, capable of objectivity and critical thought, but it suffers from a sense of alienation – the cost of relinquishing the participatory unity. (It “dissolves the semantic unity” of earlier ages – e.g. pneuma gets split into multiple concepts: mind vs matter, spirit vs wind.) Historically, one can place the dawn of onlooker consciousness around the Axial Age (c. 500 BCE) for some cultures (as abstract ethics and rationality emerged), but Barfield emphasizes it truly became dominant by the 17th–18th centuries CE, with the triumph of scientific materialism.

- Final Participation: Barfield believed (following inspirations from Coleridge and Rudolf Steiner) that the next stage would be a conscious reunion of matter and mind – not a regression to original participation, but a higher synthesis. In “final participation,” humans would participate in the world’s life intentionally and self-awaredly, overcoming the subject-object split while retaining individuality. This could mean a future where consciousness experiences nature as alive with meaning again, but through the fully developed self, not by erasing it. Barfield saw signs of this in poetic imagination and Goethe’s “participatory” science, and considered Anthroposophy (Steiner’s spiritual science) an attempt to cultivate final participation. This stage lies in the future – if humanity can learn to reconnect with the qualitative, inner aspects of reality without losing rational clarity. It would entail a transformation of consciousness as momentous as the Axial/Scientific Revolution shift. (In temporal terms, one might speak of an incipient second Axial Age or a new epoch in the coming centuries, wherein spirituality and science are reconciled.)

Barfield’s analysis is unique in focusing on semantic evidence – for example, ancient texts and word meanings – to show that people thought and perceived differently in earlier epochs. Original Participation corresponds to the mythic consciousness of antiquity, which likely began in prehistoric times (Neolithic or earlier) and characterized civilizations like those of Homeric Greece, ancient India, etc. Onlooker consciousness took shape through late classical and medieval developments, but became the norm by modern times (Early Modern period). Final Participation is envisioned as a potential future consciousness beyond the modern mental-rational focus. Barfield’s evolutionary view is not linear-progressive in terms of “better or worse”; rather, it sees a loss (of living meaning) accompanying the gain in objectivity, which final participation must restore at a higher level.

Jean Gebser – Structures of Consciousness (Archaic to Integral)#

Jean Gebser (1905–1973), a European philosopher, described the “unfoldment of consciousness” in terms of five major structures or mutations of consciousness: archaic, magic, mythical, mental, and integral. Each structure is not merely a historical period but a way of experiencing reality, with its own spatial, temporal, and sense-of-self characteristics. However, Gebser did link these structures to broad epochs of human history. In The Ever-Present Origin (1949), he outlines:

- **Archaic Structure (zero-dimensional, “deep sleep” consciousness) – This is an original undifferentiated state of consciousness. Gebser likens it to a state of deep, dreamless sleep: a non-perspectival world where self and environment are indistinct and awareness is minimal. In the archaic structure, there is a complete identity with the whole; early humans at this stage had no developed ego and no sense of time or separation. This structure is hypothesized to correspond to the very earliest humans (perhaps early Homo sapiens or even pre-sapiens hominids). It’s “zero-dimensional” because there’s no perception of a differentiated space – it’s a point-like immersion in the all. Historical correlation: This is more speculative, but one might associate it with the Paleolithic before the emergence of symbolic art or ritual, when human consciousness was an extension of nature with only flickering self-awareness.

- **Magic Structure (one-dimensional, “sleep” consciousness) – Here a minimal separation between man and nature occurs, but consciousness is still dominated by a unity with the group and environment. The magic structure is pre-perspectival and timeless: early humans in this mode live in a kind of dream-like engagement with nature, full of animistic and collective consciousness. The world is enchanted – objects and events are linked by participation mystique (mystical connections). The self is barely distinguished; security and identity come only within the tribe or clan. Magic consciousness is one-dimensional in Gebser’s terms: life is viewed along a single “line” of affect and linkage (one thing directly influences another via magic, without an abstract space between). Language is gestural or incantational rather than propositional. Historical correlation: This corresponds to tribal societies of the Paleolithic and Mesolithic. Gebser associates the transition from archaic to magic with the mythical “Fall of Man” – the point at which humans left the purely instinctual Eden and started using primitive symbols or rituals. In more concrete terms, by the time Upper Paleolithic cave paintings and shamanistic rituals appear (c. 30,000–10,000 BCE), we see evidence of magical consciousness – humans attempting to influence reality through ritual, identifying with totem animals, etc.

- **Mythical Structure (two-dimensional, “dream” consciousness) – In the mythical structure, imagination and symbolic narrative bloom. Consciousness becomes bi-polar: humans perceive the world in dualities and polarities (e.g. light/dark, good/evil, male/female gods) and express it through myths and symbols. Gebser calls it two-dimensional because it introduces a sense of inner vs outer, or a symbolic space where opposites interact (like the “plane” of a story or a mandala). Time in the mythical structure is rhythmic and cyclic (the time of seasons, of eternal return), rather than purely timeless like the magic or linear like the mental. The self is now a participant in stories – individuals identify with roles (a member of a lineage, a follower of a deity) in a larger cosmic drama. Language and art become richly figurative (e.g. epics, mythic art). Socially, this structure emerges with the rise of agriculture and early high cultures, where solar and lunar deities, creation myths, and tribal epics guide the worldview. Gebser notes that by the time large settlements and the cult of great gods and goddesses arise, mythical consciousness is in effect. Historical correlation: Roughly the Neolithic through Bronze Age (say 10,000 BCE up to ~500 BCE in some areas). For example, ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Indus Valley, early China, etc., with their elaborate mythologies and god-kings, were operating largely in a mythical structure. (Gebser cites that mythical consciousness reached its height in the high civilizations circa 3000–1500 BCE, where ritual, myth, and cosmic kingship were dominant.).

- **Mental (Mentallo-rational) Structure (three-dimensional, “wakeful” consciousness) – The mental structure is the mode of thought familiar to modern Western mind: it is perspectival, analytical, and oriented in linear time and three-dimensional space. This structure “breaks the mythical polarity” by introducing focused rationality and ego. Here, the ego becomes fully distinct – the “I” stands apart from the environment and even from the collective myth. Perspective in painting (developed in the Renaissance) is a metaphor: mental consciousness sees the world as extending in homogeneous space, from a clear viewpoint. Time is seen linearly (history, progress) rather than cyclically. According to Gebser, the mental structure began to crystallize with the ancient Greeks – he specifically points to around the 6th–5th century BCE (the time of Greek philosophy, early science, and the Socratic awakening of critical self-awareness). This corresponds to what Karl Jaspers termed the Axial Age, when rational reflection emerged across cultures. In the mental structure, logical thought, argument, and objective analysis come to the fore. By the late Middle Ages and Enlightenment in Europe, the mental-rational mode fully dominates – giving us modern science, formal logic, and the concept of a personal identity existing through chronological time. Historical correlation: The seeds of the mental structure appear around the first millennium BCE (Greek philosophy, the rational elements in Buddhism/Confucianism, etc.), but Gebser sees its full flowering in the modern era (17th–20th centuries CE) when rationalism, individualism, and empirical science reign. Today’s “mental structure” is evident in how we compartmentalize reality, objectify nature, and emphasize quantitative, sequential thinking. It’s a three-dimensional world in that we experience space with depth (perspective) and can project coordinates; similarly, thought can synthesize multiple factors in a unified mental “space.” This structure achieved immense successes (technology, systematic philosophy) but also one-sidedness, leading to a crisis (the discontents of modernity).

- **Integral Structure (fourth-dimensional, “aperspectival” consciousness) – Gebser proposed that in the 20th century a new mutation was underway: the Integral or aperspectival structure. “Aperspectival” means beyond single-point perspective – a consciousness that can integrate all previous structures (archaic, magic, mythic, mental) without getting stuck in any one. It is termed four-dimensional to indicate inclusion of time as an ever-present, transparent dimension (sometimes called “time-freedom”). In practical terms, integral consciousness transcends the subject-object dualism of the mental structure and the polarized either/or of the mythic; it sees through and includes them. Gebser described it as a “transparent” or diaphanous world where whole systems and multiple dimensions are perceived at once. This might manifest as an ability to hold paradox, unify intuition and analysis, and be present in the flow of time rather than boxing reality into fixed coordinates. Gebser saw evidence of the integral mutation in modern art (e.g. Picasso’s cubism showing multiple angles at once), physics (relativity and quantum theory breaking the single reference-frame perspective), and a growing interest in holistic thought in culture. The integral structure is not just a concept but an actual transformation in how consciousness operates – moving toward what he called “aperspectival world” where time and space are no longer limiting or fragmenting awareness. Historical correlation: If real, the integral structure would be emerging in the 20th–21st centuries and beyond. It does not have a full societal manifestation yet (it’s an incipient mutation), but pioneers and creative individuals exemplify it. It aims to resolve the crisis of the mental stage by overcoming the alienation and fragmentation of modern consciousness, somewhat analogous to a second Axial Age or a leap to planetary consciousness. Gebser emphasized this is not a future utopia to wait for, but a structure already coming into being that demands our participation.

Importantly, Gebser did not consider these structures simply replaced one another – rather, each new mutation transcends and includes the prior. All earlier structures (magic, mythic, etc.) remain “co-present” in us. For example, modern humans still have magical and mythic elements (in art, dreams, instinctual reactions), but under the dominant mental structure they have been repressed or unconscious. The integral structure would consciously integrate them. Gebser’s work is not strictly “linear progress” (he avoids calling later structures “better” in a moral sense) – it’s about unfoldment of latent possibilities of consciousness.

(Historical mapping summary: Archaic – corresponds to early prehistory, the indistinct consciousness of the hominid and early Homo sapiens era. Magic – corresponds to tribal Paleolithic-Mesolithic cultures, pre-agricultural shamanic times. Mythic – corresponds to the agrarian and early urban civilizations (Neolithic, Bronze Age, into the Iron Age) when myth and ritual ruled cognition. Mental – emerges around the Axial Age (800–200 BCE) and dominates by the modern period (1500 CE onward), characterizing the consciousness of contemporary civilization (rational, individualistic). Integral – a nascent structure appearing in the last century, potentially characterizing a future (or dawning) global culture that transcends the earlier limitations.)

Teilhard de Chardin – Cosmic Evolution of Consciousness (Noosphere to Omega)#

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955), a French paleontologist and Jesuit, advanced a grand evolutionary vision in which consciousness increases in tandem with complexity in the universe. He outlined a trajectory from the formation of the Earth to the far future, with key transitions:

- Geosphere: Initially, Earth is just inanimate matter. (No life or consciousness – just physics and chemistry.)

- Biosphere: Life emerges, and with it biological forms of consciousness (basic sentience, perception in animals). Over millions of years, evolution produces more complex organisms with higher nervous systems.

- Noosphere: With the rise of humankind, reflective thought appears and envelops the planet as the “noosphere” (from Greek nous, mind) – essentially a sphere of mind or collective human thought encircling the Earth. Teilhard saw the noosphere as a new layer on Earth, just as the biosphere (life) overlaid the geosphere (rocks). Human consciousness is thus a geologically significant phenomenon. Over historical time, the noosphere grows in density and interconnectedness (especially as population increases and communications link everyone).

- Omega Point: Teilhard speculated that evolution is converging toward a supreme point of consciousness he called the Omega Point. This would be the culmination where individual minds form a unified whole (a “hyper-personal” collective consciousness, possibly identified with the Cosmic Christ in Teilhard’s Christian framework). At Omega, the noosphere would attain maximum complexity and maximum consciousness, effectively becoming one with the divine.

Teilhard’s model is teleological – evolution has a direction: toward greater complexity and consciousness. In the earliest ages (pre-life), there was no consciousness manifest. With life’s evolution (from single cells to animals), there was an increase in what he called “within-ness” (interiority). But a critical threshold was crossed with early humans (perhaps in the Paleolithic) when self-aware thought ignited. After that “fire” of reflective consciousness was lit, cultural evolution took over from biological evolution. The noosphere has been developing throughout human history – for example, the creation of language, then writing, then science and technology, are milestones in the noosphere’s growing organization. Teilhard even foresaw, metaphorically, the internet or a global network as the noosphere knitting itself (he wrote about a “tightly interwoven web” of human thought covering the globe). In his view, we are currently in the midst of this noospheric evolution, heading toward a critical convergence.

He placed Omega in the far future: the point at which consciousness becomes total and convergent. Though speculative, one can interpret this as humanity reaching a collective higher consciousness, perhaps through spiritual development or some kind of global mind. Teilhard identified Omega with God, suggesting that evolution is essentially the world spiritualizing itself.

In summary, Teilhard’s history of consciousness goes from zero (inanimate) to diffuse (in animals) to self-reflective (in humans) to potentially unified (in a global divine consciousness). Unlike others in this list, Teilhard’s model encompasses the entire cosmic scale of evolution and is both scientific and theological. He was writing in the mid-20th century, inspired by discoveries in paleontology and anticipating future social integration.

(Historical mapping: Pre-life: up to ~3.5 billion years ago – no consciousness. Life’s evolution: ~3.5 billion to a few million years ago – gradual emergence of perceptual awareness (Teilhard doesn’t break this into stages here, but one could note mammalian brains developing emotional consciousness, primates with higher cognition, etc.). Noosphere: begins with the evolution of Homo sapiens – Teilhard emphasized the moment when humans could think about thinking (somewhere in late Paleolithic). A specific milestone could be the Upper Paleolithic “creative explosion” (~50,000 years ago) when art and complex tools appear – indicating symbolic thought. From then, the noosphere intensifies: Neolithic agriculture creates higher social complexity (more minds interacting), the rise of civilizations spreads ideas, the Axial Age (~500 BCE) multiplies high-level philosophies (a surge in reflective consciousness), the scientific revolution and modern era massively increase knowledge and global connectivity. Teilhard died before the digital age, but his concept presages the Internet and globalization as accelerating noospheric connectivity. The ultimate Omega Point is outside history as we know it – a possible future singularity of consciousness.)

Karl Jaspers – The Axial Age (The “Great Leap” in Consciousness)#

Karl Jaspers (1883–1969), a German-Swiss philosopher, introduced the concept of the “Axial Age” (Achsenzeit) to denote a pivotal era (roughly 800–200 BCE) when multiple civilizations independently underwent a profound transformation in thought. During this period, according to Jaspers, human consciousness took a decisive step upward – “man becomes conscious of Being as a whole, of himself and his limits,” and the fundamental frameworks of philosophy and religion were born. Key aspects of Jaspers’ Axial Age thesis:

- Concurrent Transformations: Remarkably, in several regions – China, India, the Near East, and Greece – between the 8th and 3rd centuries BCE, there was an outpouring of new thinking. For example: in China, Confucius, Laozi and the Hundred Schools of thought laid the basis for ethical and metaphysical philosophy; in India, the Upanishadic sages, Buddha, and Mahavira (Jainism) revolutionized spiritual thought; in the Middle East, Hebrew prophets like Isaiah and Jeremiah redefined religion morally, and Zoroaster (if dated then) introduced a cosmic dualism; in Greece, the pre-Socratics, then Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle invented rational philosophy, history, and science. All these emerged almost synchronously, without direct contact in most cases. It’s as if the human mind “pivoted” on its axis and started seeing the world in a new light everywhere.

- Demythologization and Transcendence: Jaspers noted that Axial Age thinkers exhibit a move away from myth and local ritual toward abstract, universal principles. There is a new reflective distance: they question the inherited myths and ask about the origin, the cosmic order, the meaning of good and evil, and the inner self. This era introduced concepts like the Dao, Brahman/Atman, Platonic Forms, the Hebrew one God concerned with ethics – all representing a transcendent reality beyond the concrete here-and-now. Humans in this age become self-aware as individuals responsible for their destiny (think of Socratic introspection or Buddhist self-analysis). There’s also an emergence of second-order thinking – thinking about thinking, or questioning how we know (e.g. Greek logic, Indian logic, Chinese dialectics). Essentially, the Axial Age planted the seeds of rational consciousness and universal moral conscience, which broke the spell of purely local, traditional worldview.

- Universality and Ethics: The Axial sages often claimed their insights were valid for all humanity, not just their tribe or city. For instance, the idea of a single universal truth (Logos, Dharma) or a universal ethic (the Golden Rule, etc.) arose. This reflects a widening of consciousness to encompass the human condition as a whole. Jaspers saw this as a birth of “moral consciousness” – awareness of the distinction between how things are and how they ought to be, applying to all people.

Jaspers’ hypothesis contributes to the history of consciousness by highlighting that not all change is gradual – there can be an epochal leap. The Axial Age was like the adolescence of humanity’s mind, after a long childhood of myth. Once this breakthrough happened, the spiritual and intellectual foundations of all later civilizations were set. We today still operate largely within the frameworks those Axial geniuses created (world religions, philosophy, science). Jaspers considered whether we might be in a Second Axial Age now (with global, postmodern consciousness emerging), but that’s more speculative.

(Historical mapping: The Axial Age is explicitly dated ~800 BCE – 200 BCE. Key exemplars: Greek city-states from classical period, the Hebrew Kingdoms & Exile period prophets, the late Vedic age to early Buddhist period in India (~Upanishads around 800–500 BCE, Buddha ~5th c. BCE), and the Eastern Zhou era in China (Confucius ~6th c. BCE, Warring States philosophers up to 3rd c. BCE). The concept doesn’t extend to every culture (e.g. Jaspers didn’t include Mesoamerica, etc., which had different timelines). But generally, it coincides with the Iron Age and early empire period, when old Bronze Age empires had fallen or weakened, giving space for new ideas. Before the Axial Age, consciousness was largely mythic-tribal (local gods, ritual-centric, uncritical); during and after, one sees the rise of reflective, individual, and universal modes of thought that characterize “classical” civilizations.)

Ken Wilber – Spectrum of Consciousness (From Archaic to Postmodern and Beyond)#

Ken Wilber (b. 1949), an American integral theorist, synthesized many developmental models (including several above) into a broad narrative of the evolution of consciousness. In works like Up from Eden (1981), Wilber describes a sequence of stages through which human consciousness has collectively unfolded. He draws terminology from Freud, Jung, Neumann, Gebser, etc., and correlates stages with anthropological eras. A simplified outline of Wilber’s spectrum:

- Pleromatic / Archaic: The first glimmerings of human awareness – an embedded, instinctual consciousness at the “dawn of the human race”. Wilber (citing Jean Gebser and Erich Neumann) calls this pleromatic-uroboric, meaning the person is merged with nature (like Neumann’s uroboros). It’s the state of early hominids or the very earliest Homo sapiens: undifferentiated self, focus on basic vital drives (food, warmth). Historical: Wilber suggests this prevailed in our hominid ancestors of the Lower Paleolithic, before true self-awareness.

- Typhonic (Magic-Animistic): This stage marks the emergence of a distinct but body-bound sense of self, still embedded in nature’s flux. “Typhonic” (a term from Neumann, referring to the Egyptian monster Typhon) implies a fusion of the personal and natural – the self is not well separated from the body or environment. Consciousness here operates via magical thinking and images, with no clear distinction between subjective wishes and objective events. The world is alive with powers, and the individual ego is only loosely formed, often identified with the body. Death fear begins to appear as time is dimly sensed. Wilber associates this with Neanderthal and early Homo sapiens (Cro-Magnon) in the Middle Paleolithic. Indeed, around 200,000–50,000 years ago humans show first burials and ritual behaviors, suggesting an incipient self and magical beliefs. In myths, this era is symbolized by titans and sorcerers (Wilber mentions the Sorcerer of Trois-Frères cave painting as emblematic art). Historical: roughly 200,000 – 40,000 years ago, covering the middle Paleolithic; by the Upper Paleolithic (40kya), the magical-typhonic consciousness was in full swing (cave art, shamanism).

- Mythic Membership: With the advent of agriculture and larger societies, consciousness evolves into a mythic, role-based mode. Here the self is now identified with the tribe or social order (“membership”) and defined by roles and rules. There is a strong sense of mythic imagination – the world is governed by gods and cultural heroes, and human life is enmeshed in grand narratives. The ego is more developed than in the magic stage, capable of suppressing immediate instincts (hence agriculture, delayed gratification) and adhering to shared myths and laws. Wilber notes this stage coincides with the rise of farming, settlements, and God-Kings; socially, circa 10,000–1,000 BCE. It is marked by “cults of the Great Mother” and later sky-father deities, by societal hierarchy, and extensive use of language and narrative. Death is coped with via elaborate rituals (sacrifice, mummification) reflecting mythic beliefs of afterlife. Wilber gives a timeline: mythic membership was most fully expressed between about 4500 and 1500 B.C.. That corresponds to the Bronze Age civilizations (Egyptian, Mesopotamian, early Indo-European, etc.) where indeed we see the peak of mythic religious culture. In this view, early civilizations were mythic-membership consciousness: individuals saw themselves primarily as members of a collective (clan, caste, city-state) under the guidance of sacred narratives.

- Mental-Egoic (Rational): This structure emerges out of the mythic around the time of the Axial Age, and comes to dominance in the modern era. It is characterized by a rational, conceptual ego – the self that can reflect on itself, use logic, and perceive linear time and history. Wilber associates the “mental” (in Gebser’s sense) or “egoic” stage with the late Bronze Age into Iron Age: its lower forms start ~2000 BCE and its high forms by the Classical Greek period (c. 500 BCE). In this stage, individuality and reason bloom: one steps out of mythic immersion and can criticize myths as mere stories. There’s the development of philosophy, science, formal religion and ethics (think of Greek philosophy, the Buddhist dhamma, etc., all emerging after 1500 BCE). By the modern period, this rational egoic consciousness reigns – valuing personal autonomy (“sanctity of personhood”), empirical truth, and self-agency. Wilber notes the egoic stage brought tremendous advances (rational comprehension, historical sense) but also new perils: egoic beings feel separate and mortal, which led to existential anxiety, pursuit of egoic immortality projects (conquests, monuments), and large-scale warfare and oppression unheard of in tribal times. The modern mental ego thus has been both powerful and problematic – enabling technology and individual rights, but also ideologies, imperialism, and spiritual emptiness. Historical: This stage spans roughly from the Axial Age (1st millennium BCE) through the Enlightenment and up to today. We are still largely “mental-rational” in our average consciousness, according to Wilber, especially in the developed world.

- Higher Transpersonal Stages: Wilber, integrating Eastern mysticism, argues that evolution can continue beyond the ordinary ego. He speaks of potential transpersonal stages – sometimes labeled the psychic, subtle, causal, and nondual – which historically have been accessed only by a few individuals (mystics, sages) but might represent future general stages. In Up from Eden, he didn’t elaborate much on these in a historical sense, except to say that throughout each era, a few individuals reached beyond the average stage to the next. For example, in the mythic age, certain saints achieved a subtle oneness (mystical unity with the Great Mother goddess). In the current mental age, some have attained “psychic” or “causal” consciousness (e.g. Buddhist enlightenment, yogic samadhi) pointing to humanity’s future evolution. Wilber is optimistic that humanity as a whole can evolve to a higher, more integral or spiritual consciousness, moving beyond the alienated ego toward a holistic, compassion-based awareness akin to what Gebser called integral or what he himself calls Vision-logic and beyond.

Wilber’s framework is comprehensive, and he often provides dates and examples. For instance, as cited above, he places the magic-typhonic stage in Neanderthal/early Homo sapiens times (an Upper Paleolithic culture figure like the Sorcerer of Trois Frères cave painting (~13k BCE) is emblematic). The mythic stage he correlates with the rise of agriculture (~8000 BCE) and peaking around the time of the Bronze Age kingdoms (4500–1500 BCE). The egoic-rational stage begins to stir by the late Bronze Age (Second millennium BCE) and fully manifests by classical Greece and onward. Wilber explicitly notes that by the second millennium B.C. some early egoic developments occurred (perhaps the strict monotheism of Akhenaten, the rationalism of some Upanishads), but it required the Axial breakthrough to come to the forefront. Today’s world is largely at this egoic-rational level, with postmodern developments hinting at an emergent integral stage.

Wilber also emphasizes that at any given time, not all humans are at the same consciousness level – there’s a spectrum. E.g., even in modern society, some individuals or subcultures might operate from mythic (fundamentalist religion) or even magic (superstition), while leading-edge thinkers might be heading into integral. But the center of gravity of global consciousness can shift over millennia.

(Historical mapping summary: Archaic/uroboric: early human ancestors (before 50,000 BCE). Typhonic/magic: later Paleolithic (50,000–10,000 BCE, hunter-gatherers with shamanic-magical worldviews). Mythic: Neolithic and Bronze Age (agricultural tribes to early states, 10,000–500 BCE, dominated by myth and collective order). Mental-egoic: Axial Age and especially modern era (500 BCE – present, dominated by rational individual consciousness). Integral/Transpersonal: nascent in a minority now, possibly general in the future (21st century onward).)

Prehistoric cave art (such as the Cueva de las Manos hand stencils in Argentina, c.7000 BCE) reflects an early form of consciousness. In the magical-animistic worldview of our Upper Paleolithic ancestors, individual identity was deeply merged in group and nature – these hand prints may have been a ritual of belonging or sympathetic magic. Such artifacts hint at a mentality without a fully separate ego, participating mystically in the surrounding world, characteristic of “original participation” or magic structure stages of consciousness.

Rudolf Steiner (Anthroposophy) – Cultural Epochs and the Evolution of the “I”#

Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), an Austrian esoteric teacher, proposed a complex evolutionary timeline for human consciousness, drawing from Theosophical concepts of root races and adding his own insights. Steiner’s model spans great epochs of Earth evolution and smaller cultural ages, during which human consciousness gradually shifts from a dreamy, picture-conscious state to the waking intellectual consciousness we know, and will move further to spiritual levels. A brief overview:

- Atlantean and Pre-Atlantean Epochs: Steiner spoke of ancient epochs predating recorded history – Lemurian and Atlantean – during which human beings existed in more subtle forms of consciousness. In those times (which he esoterically dates to tens of thousands of years ago, ending around 8000 BCE with the sinking of Atlantis), humans had a “dreamlike clairvoyance.” They perceived spiritual realities directly but had little waking ego. For example, he claimed Atlanteans had tremendous memory and lived in images, but not logical abstract thought. Individuals did not experience themselves as sharply separate from their tribe or nature – a group-soul consciousness prevailed (similar to the magic/mythic structures in other models). Steiner indicated that our current form of self-aware “I” only fully incarnated at the very end of the Atlantean epoch. In Atlantean times, language and memory were developing, but the instinctual, nature-connected consciousness was still strong. He describes that early Atlanteans could literally affect matter via sound and will – suggesting that what we call magic was a natural endowment of that consciousness. After a series of sub-stages, Atlantis fell (Steiner’s narrative parallels the flood myths), and survivors carried a more individuated consciousness into new lands.

- Post-Atlantean Cultural Epochs: Following Atlantis, Steiner divides the current epoch (which he dates ~7227 BC to far future) into a sequence of seven cultural ages. Each cultural age lasts ~2,160 years (he associates this with zodiacal ages). These are: Ancient Indian, Ancient Persian, Egypto-Chaldean, Greco-Roman, Modern (Anglo-Germanic), and two future ages (the 6th and 7th post-Atlantean ages). In each, the general character of consciousness shifts slightly, building upon the previous. For instance, during the ancient Indian age (c. 7227–5067 BCE), people still had a strong atavistic clairvoyance – a living experience of spiritual reality – which is reflected in the Vedic wisdom (a dreamy, imaginative consciousness connected to cosmic spiritual truths). By the Egyptian–Babylonian age (c. 2907–747 BCE), consciousness had become more sense-oriented and intellectual – think of how in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, math, astronomy, and engineering developed, and ego distinctions (like personal ambition for immortality in tombs) grew, though still within a mythic context. Steiner considered the Greco-Roman age (747 BCE – 1413 CE) crucial: here the intellectual mind was born – the Greeks developing logical thought and self-reflective philosophy, and later the Romans solidifying legal, abstract concepts of personhood. During this period (especially by its end around the Renaissance) the consciousness soul or intellectual soul fully emerged – meaning humans started to experience themselves as individual “I” beings sharply separate from the spiritual world. Finally, in the current 5th post-Atlantean age (1413 CE – present), we have the fully intellectual, materialistic consciousness – the zenith of separative ego and analytical thinking (hence science, industry, and also spiritual darkness as per Steiner). The mission of our age, he said, is to develop the Consciousness Soul – fully individualized, self-conscious mind – which we are doing, but it also brings the risk of falling into complete soulless materialism. Looking ahead, Steiner prophesied the 6th epoch will begin around 3573 CE, wherein those who have prepared will develop a new spiritual clairvoyance (a reunion with the spiritual world but now with fully conscious “I”). Eventually, by the end of the 7th age and this whole cycle, humanity will transcend the physical plane.

- Progressive Incarnation of the Ego: A core theme in Steiner’s evolutionary view is that the human Ego or “I” (the spiritual self) has been gradually incarnating deeper over time. In very ancient epochs, humans were more like children, directed by group souls and divine beings (hence myth of gods walking among men). As epochs passed, the Ego sank in, gaining independence. For example, he said in Atlantis humans had an emotional/psychic connection but not yet intellectual self-awareness; after Atlantis, the Ego enters the intellectual mind (in Greeks, one sees the first clear self-conscious personalities like Socrates, who says he has a daimonion – an inner voice, indicating inner ego activity). By modern times, the Ego is fully in the physical-sensory realm, which allows objective consciousness but also isolation. This trajectory – from a clairvoyant participation with spiritual nature to individualized rationality – mirrors other models (original participation → onlooker, or mythic → mental). Steiner’s unique contribution is embedding it in a grand cosmological drama with reincarnation and karma, and predicting future spiritual stages.

In sum, Steiner’s evolutionary model of consciousness agrees that early humanity had a sleep-like, picture consciousness (mythic/magic) which slowly brightened into our awake, self-aware thought. He gives esoteric chronological markers: the Atlantean catastrophe (~8k BCE) as a turning point when “group-soul” clairvoyance receded and the intellectual ego started developing. The Greco-Roman period (~1st millennium BCE) as when intellectual rationality firmly took root, and the 15th century CE as the dawn of the fully modern consciousness soul age. Steiner’s vision extends into the future, foreseeing a next big leap where our present form of consciousness (which he saw as the 5th epoch out of 7) will itself be superseded by a more spiritual, intuitive mode in the 6th epoch. Each epoch is both a spiritual learning process and a recapitulation: interestingly, Steiner noted that the cultural epochs recapitulate earlier great epochs in a higher form (e.g., the 5th epoch in which we live in some ways mirrors the long-ago 5th Atlantean sub-race in theme). He also warned against racism or linear supremacism – he stressed that the term “race” properly applies only to Atlantis; in the post-Atlantean times it’s about culture and consciousness, not biological race.

(Historical mapping: Steiner’s timeline isn’t orthodox by scientific standards, but roughly: Lemurian epoch – a very distant past (perhaps millions of years ago) where humans were non-physical or very different, consciousness akin to deep trance; Atlantean epoch – a lost continent age (perhaps ~100k–10k BCE) where humanity had etheric clairvoyance, memory developing; Post-Atlantean epoch – from ~8000 BCE to ~AD 8000, divided into cultural ages: Ancient India (oldest historical civilizations, high dreamy spirituality), Persia (c. 5000 BCE, early agriculture, dualistic worldview), Egypt/Chaldea (3000–~700 BCE, pragmatic and magical-astral consciousness), Greco-Roman (700 BCE – 1400 CE, rational mind dawning), Modern West (1400 CE – present, full intellectual ego and material science), and two more to come. Steiner aligns key transitions with real events: e.g. end of Egyptian epoch ~747 BCE (birth of Greek philosophy shortly after), end of Greco-Roman ~1413 CE (Renaissance era begins). By Steiner’s account, the consciousness of ancient peoples (Egyptians, early Indians, etc.) was fundamentally different – more pictorial and less self-reflective – than that of a modern person, which is consistent with other theorists but Steiner provides a uniquely detailed spiritual narrative for it.)

A modern integral model of consciousness evolution is Spiral Dynamics, based on Clare Graves’ research. It identifies a sequence of value-memes (vMEMEs) denoted by colors: Beige (archaic survival), Purple (magical-animistic tribalism), Red (egocentric power), Blue (mythic order and purpose), Orange (rational achievement), Green (pluralistic egalitarianism), and beyond. This spiral diagram illustrates that each stage is a core worldview through which people and societies have evolved. For example, Beige corresponds to prehistoric survival bands, Purple to tribal mystical cultures, Red to warlord societies (Bronze Age chiefdoms), Blue to traditional civilizations with organized religion and authority (Axial Age empires, medieval period), Orange to the modern scientific-industrial worldview, and Green to the postmodern, humanistic worldview emerging in recent decades. The model suggests that humanity as a whole is moving up this spiral, with each stage adding more complexity and inclusiveness (while individuals and subcultures can be at different levels). Higher tiers (Yellow, Turquoise) are projected as integrative stages beyond Green. Spiral Dynamics thus recapitulates many ideas above in a contemporary psychological framework.

Andrew Cutler – Eve Theory of Consciousness (The Snake Cult of Recursion)#

Andrew Cutler (b. 1949), a contemporary researcher in psychology and AI, has proposed one of the most provocative modern theories of consciousness evolution in his Eve Theory of Consciousness (EToC) (mirror). Published in 2025, Cutler’s theory attempts to bridge the gap between the anatomical modernity of Homo sapiens (appearing ~200,000 years ago) and the behavioral modernity evidenced in art, language, and complex culture (emerging ~50,000 years ago). His central thesis is radical: women discovered recursive self-awareness first and taught it to men through entheogenic rituals involving snake venom.

The Recursion Revolution#

Cutler builds his theory on the foundation that recursive thinking – the ability for a mental process to call itself, creating self-reference – is the essential feature distinguishing human consciousness. Drawing from linguist Noam Chomsky’s work on recursive grammar and computer science principles, Cutler argues that recursion enables not just complex language, but the core of conscious experience itself: the ability to think “I am.”

According to Cutler, early humans lived in what he calls a “pre-recursive” state – capable of basic cognition and even primitive culture, but lacking the self-reflective “I” that characterizes modern consciousness. The transition to recursive thinking wasn’t instantaneous but occurred over thousands of years, creating what he terms the “Valley of Insanity” – a period when humans had glimpses of self-awareness but couldn’t maintain it consistently, leading to what we might now recognize as schizophrenia-like symptoms.

The Snake Cult Hypothesis#

The most striking aspect of Cutler’s theory is his proposal that snake venom served as the primordial entheogen – a consciousness-altering substance used to facilitate the first experiences of self-awareness. He documents extensive evidence for the ritual use of snake venom across cultures, from ancient Greece (the Eleusinian Mysteries) to modern India (where gurus like Sadhguru still consume venom for spiritual purposes).

Cutler argues that snake venom’s unique properties made it ideal for consciousness expansion: it contains high concentrations of Nerve Growth Factor (NGF), which promotes brain plasticity, and produces altered states similar to other psychedelics but with the crucial difference that snakes find humans, making the first encounters involuntary rather than sought out. This, he suggests, explains the universal association of serpents with wisdom and consciousness in world mythologies.

The Primordial Matriarchy#

Central to the EToC is the claim that women achieved recursive consciousness before men. Cutler marshals evidence from evolutionary psychology, neuroscience, and anthropology to support this:

- Evolutionary pressure: Women’s survival during pregnancy and childrearing required sophisticated social navigation, language skills, and coalition-building – all domains that would select for recursive social cognition.

- Neurological differences: The X chromosome has disproportionate influence on brain areas involved in language, social cognition, and self-referential thinking. Recent studies show extraordinary selection pressure on X-chromosome genes related to neural development in the last 50,000 years.

- Archaeological evidence: Early symbolic artifacts often show female bias – from Venus figurines (possibly self-portraits reflecting newfound self-awareness) to cave art handprints (75% left by women).

This female advantage would have created what Cutler calls a “primordial matriarchy” – not necessarily complete female dominance, but women’s leadership in the crucial domain of inner life and spiritual culture.

Global Diffusion and Cultural Memory#

Cutler addresses the global similarity of creation myths and serpent symbolism by proposing that the Snake Cult consciousness rituals spread worldwide between 30,000-50,000 years ago. He traces evidence for this diffusion across continents:

- Mythological parallels: The consistent association of serpents with consciousness-granting (Genesis, Egyptian Neheb-ka, Chinese Nuwa, Australian Rainbow Serpent) suggests shared cultural memory rather than independent invention.

- Ritual artifacts: The global distribution of bullroarers (sacred instruments) used in male initiation ceremonies, often described as having been “stolen from women,” provides physical evidence of ritual diffusion.

- Linguistic traces: The similarity of first-person pronouns (ni/na) across diverse language families worldwide may reflect the spread of the word “I” along with consciousness-teaching rituals.

Timeframe and Evolution#

Unlike some consciousness evolution theories that push human specialness back hundreds of thousands of years, Cutler places the crucial transformation relatively recently:

- 50,000 years ago: First glimpses of recursive consciousness in a small population, likely women with genetic advantages for self-referential thinking.

- 40,000-30,000 years ago: Development of snake venom rituals to reliably induce and teach the “I am” experience; beginning of global cultural diffusion.

- 20,000-10,000 years ago: Recursive consciousness becomes stable and universal through cultural-genetic coevolution, ending the “Sapient Paradox” of delayed behavioral modernity.

Cutler argues this timeline explains several puzzles in human evolution: why behavioral modernity was delayed so long after anatomical modernity, why it appeared at different times in different regions, and why there was such rapid cultural acceleration once it began.

Weak vs. Strong EToC#

Cutler distinguishes between two versions of his theory:

Weak EToC: Recursive culture spread and created selection pressure for recursive cognitive abilities, leading to the evolution of modern consciousness over tens of thousands of years. This requires only that culture can influence evolution, which is well-established.

Strong EToC: The specific rituals developed by women using snake venom were crucial for the spread of consciousness, and creation myths like Genesis preserve actual cultural memories of this transformation. This makes specific predictions about archaeological evidence, genetic selection patterns, and mythological analysis.

Implications and Controversies#

The Eve Theory of Consciousness is intentionally provocative, challenging both religious and scientific orthodoxies:

- It suggests that biblical and mythological accounts may contain historical truth about consciousness evolution, rather than being mere metaphor or fabrication.

- It proposes that human nature has evolved significantly in the last 50,000 years, contrary to the common scientific assumption that we are essentially unchanged since anatomical modernity.

- It places women at the center of humanity’s most crucial evolutionary transition, supported by evidence but challenging patriarchal narratives.

Modern Relevance#

Cutler connects his theory to contemporary concerns about artificial intelligence and consciousness. He argues that understanding how recursive self-awareness emerged in humans – through culture, pharmacological assistance, and gradual genetic-cultural coevolution – might inform how we approach the development of artificial general intelligence. The transition from pre-recursive to recursive consciousness represents humanity’s only example of general intelligence emerging, making it crucial to understand as we create new forms of intelligence.

(Historical mapping: Cutler’s model places the pre-recursive archaic stage in early Homo sapiens (200,000-50,000 years ago), characterized by sophisticated tool use and basic culture but lacking stable self-awareness. The recursive transition begins around 50,000 years ago with the first glimpses of self-consciousness in women, accelerates with the development of snake venom rituals and cultural diffusion (40,000-30,000 years ago), and concludes with universal stable consciousness by the end of the Paleolithic (10,000 years ago). Unlike other models, EToC provides specific mechanisms (entheogenic rituals, sexual selection, cultural diffusion) for how this transformation occurred and why it left traces in worldwide mythology and religion.)

Conclusion#

As we’ve seen, many thinkers converge on the notion that human consciousness has a history – an evolution from primitive, embedded awareness to the complex, reflective mind of today, and possibly to new forms tomorrow. Despite their differing terminologies and philosophies, these models show some striking commonalities:

- Earliest humans likely had a non-separate, “merged” consciousness (whether termed archaic, pleromatic, or original participation) akin to a dim dream state embedded in nature and instinct. This gradually gave way to a magical-animistic mentality where mythic imagination and group psyche prevailed (the world of spirits, totems, and symbols archeology glimpses in prehistoric art). This corresponds to the hunter-gatherer and early tribal era in prehistory.

- With the rise of agriculture and civilization, a mythic or theological consciousness took center stage – humans defined themselves through mythic narratives, divine kingships, and collective identities. This era (Neolithic through Bronze Age) saw the flourishing of polytheistic religions, grand myth epics, and the first ethical codes, indicating a richer inner life but still embedded in myth and tradition.

- Around the middle of the first millennium BCE (the Axial Age), a mutation occurred in several cultures: rational, reflexive consciousness was born. Individuals (like the Greek philosophers, Hebrew prophets, Indian sages, Chinese philosophers) started to think abstractly and self-critically, breaking the spell of mythic immediacy. This paved the way for mental-egoic consciousness – the mode of thought grounded in reason, individual identity, and empirical observation. Historically, this maps onto the classical antiquity and firmly takes hold in the modern era with science and humanism.

- In modern times (especially post-17th century), humanity at large operates with a separate individual ego and analytical intelligence – what many call the mental-rational or onlooker consciousness. This has allowed tremendous progress in science and autonomy but often with a loss of spiritual meaning and connectedness.

- Many of these thinkers anticipate or advocate for a further evolution: whether it’s Hegel’s absolute spirit, Comte’s positivist age (which he thought would usher unprecedented social harmony via science), Teilhard’s Omega Point of unified consciousness, Gebser’s integral structure, Wilber’s transpersonal levels, or Steiner’s future clairvoyant age – there is a common sentiment that the story isn’t over. After the fracture of the modern ego, a higher synthesis or integration could emerge, reuniting us with each other and the cosmos at a higher octave of consciousness.

Finally, it’s worth noting these models carry different emphases – some are more empirical (e.g. the anthropologists tying stages to material culture), others mystical (Steiner, Aurobindo), others philosophical (Hegel, Barfield) – yet they don’t contradict so much as complement each other. When mapped onto the timeline of (pre)history, a general outline can be drawn:

- Paleolithic (200,000 – 10,000 BCE): Archaic and Magical consciousness. Small bands, animistic rituals, no formal self-reflection. (Corresponding to Wilber’s typhonic, Barfield’s original participation, Gebser’s magic, etc.).

- Neolithic to Bronze Age (10,000 – 500 BCE): Mythic consciousness. Agricultural villages to early states, myth and religion organize thought. Emergence of some protologic in late Bronze Age. (Gebser’s mythic, Comte’s theological, Frazer’s magic giving way to religion, Vico’s age of gods and heroes, etc.).

- Axial Age (c. 800 – 200 BCE): Critical breakthrough – inception of Mental/Egoic consciousness. Philosophy, rational religion, individual spiritual salvation, science seeds appear. (Hegel’s transition from oriental despotism to Greek reason, Jaspers’s Axial shift, Gebser’s mental structure arising with Greeks, etc.).

- Classical to Early Modern (200 BCE – 1600 CE): Growing dominance of rational-mental consciousness within still-mythic frameworks (e.g. scholasticism tries to reconcile reason and faith). Renaissance and Scientific Revolution mark tipping point to full “onlooker” consciousness (objective science, secular thought). (Barfield’s onlooker fully by 17th c., Comte’s metaphysical yielding to positive, Steiner’s consciousness soul age starts 15th c.).

- Modern Era (1600 – 2000 CE): Predominantly Mental-Rational/Scientific consciousness worldwide. Industrialization, secularization. Also birth of historical self-consciousness (awareness of evolution itself) and late in this period, a pluralistic critique (postmodern “green” in Spiral Dynamics, indicating values of empathy and relativism beyond strict rational ego).