TL;DR

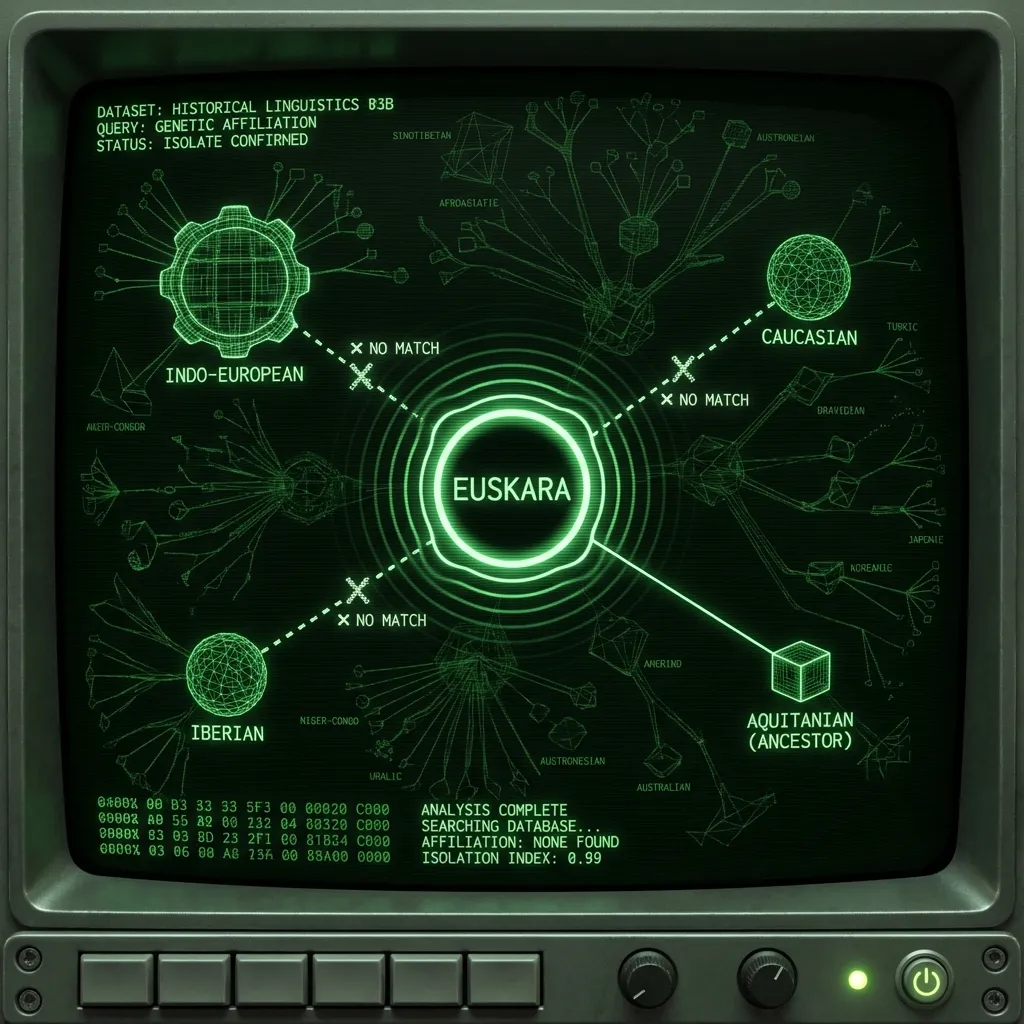

- Basque (Euskara) is classified as a language isolate because no demonstrable genetic relationship to any other known language family has been established using rigorous comparative methodology. 1

- The only securely identified ancestral relative is Aquitanian, recorded in ancient inscriptions, but it does not extend Basque into a broader family by itself. 2

- Vasconic substrate theories (e.g., Vennemann) propose a wider prehistoric family across Western Europe, but lack robust systematic correspondences and remain highly controversial. 3

- Late Basquisation situates Basque expansion and shift phenomena later in history and highlights complex contact with Indo-European languages. 4

- Much speculation (Iberian links, North African, Caucasian, etc.) fails to meet the comparative method’s standards (regular sound correspondences, shared irregular morphology). 5

“An isolate is not a claim that a language had no kin; it is a claim that we cannot demonstrate the kinship with the evidence and methods at hand.”

— Paraphrase of standard historical-linguistic definition (Campbell BLS isolates)

Basque as an isolate: definition and evidence#

In historical linguistics, a language is an isolate if it cannot be shown, through accepted comparative methodology, to belong to any language family with more than one language. This is not a metaphysical assertion about absolute disconnectedness, but a methodological conclusion based on available data and successful reconstruction criteria. 6

Basque, or Euskara, satisfies this isolate status: mainstream surveys classify it as unrelated to Indo-European languages surrounding it, and no external genetic linkage has met the strict standards for genealogical affiliation. 1

What counts as isolation here#

- No set of regular sound correspondences linking core vocabulary and morphology to any other language group.

- No shared irregular morphological paradigms that pattern across potential relatives.

- Isolates are “single-member families” in comparative taxonomy, distinct from unrelatedness imposed a priori. 6

Proto-Basque and internal reconstruction#

Comparative reconstruction within Basque dialects yields Proto-Basque (pre–Common Basque) and older layers (e.g., Old Proto-Basque), but these are stages of one language lineage, not evidence of relatives outside the baseline group. 2 The Hand of Irulegi inscription (1st century BCE) corroborates continuity of Basque or its immediate precursor. 2

The only secure extrinsic connection: Aquitanian#

The sole extrinsic linguistic entity clearly related to Basque is Aquitanian, an ancient language known from personal and deity names in Latin-script inscriptions in southwest Gaul (1st–3rd century CE). Aquitanian onomastics match reconstructed Proto-Basque elements (e.g., seni, sembe). 2

However, Aquitanian is best treated as an ancestral sister form within the same lineage, not as a separate daughter of a larger family. The corpus is too sparse to satisfy comparative subgrouping criteria toward an extended family. 2

| Source cluster | Relation to Basque | Evidence status |

|---|---|---|

| Aquitanian | Direct ancestor/close relative | Sufficient for linkage, insufficient for expansion |

| Pre-Proto Basque | Reconstruction of internal stages | Strong internal support |

| Other languages (Iberian, Caucasian, etc.) | Proposed relatives | No robust comparative support |

Major hypotheses about Basque’s broader relationships

Vasconic substrate hypothesis (Vennemann)#

The Vasconic substrate hypothesis posits a broad prehistoric family (“Vasconic”) covering Aquitanian, Basque, Ligurian, Iberian, and Proto-Sardinian elements based on substrate toponymy and lexical parallels. 3

Critique: Without systematic correspondences and shared morphological patterns that are regular over basic lexicon, such proposals remain typological and speculative, not genetic. Historical linguistics treats these as areal/typological conjectures rather than confirmed relationships.

Iberian and other ancient link proposals#

Older and fringe proposals have attempted to link Basque to:

- Iberian: superficially similar structures but far too little shared systematic material for genetic claims; mainstream linguistics dismisses Iberian as unrelated. 7

- Caucasian or Paleo-Siberian groups: typological similarities (e.g., ergativity) have been suggested, but no regular correspondences or shared paradigms have been demonstrated. 5

- Berber/North African or Uralic ties: occasional contour matches have been advanced in non-peer settings, but these lack robustness under comparative criteria.

Late Basquisation and demographic theories#

The Late Basquisation hypothesis situates Basque (or Proto-Basque) expansions and contact with Indo-European populations later in the historical period, conceiving shifts in speech communities around the Pyrenees. 4

This is not a genetic classification per se, but a historical sociolinguistic model highlighting dynamic contact zones and population movements influencing linguistics and archaeology. Its relevance lies in framing Basque’s spread and persistence, not in solving genealogical isolation.

Typology versus genealogy: what Basque resembles#

Basque’s typological profile—ergative-absolutive alignment, agglutinative morphology, extensive case system—makes it typologically distinct from neighboring Indo-European languages, but typology alone does not imply genetic relation. 8

For genealogical ties, linguists seek:

- Systematic sound correspondences across a robust base list of basic vocabulary.

- Shared irregular paradigms that resist borrowing.

- Consistent morphological homologies beyond typological shape.

None of the proposed external relatives meet these criteria to date.

Substrate and areal effects#

While Basque itself remains isolated by genetic criteria, its substrate imprint on surrounding Indo-European languages—particularly early Romance toponymy and phonological effects (e.g., loss of /f/ in early Spanish)—has been proposed in the literature. 7 These effects are contact phenomena, not evidence of genetic affiliation.

What would change the classification?#

To overturn Basque’s isolate status, evidence must demonstrate:

- Systematic sound correspondences linking Basque to another language or group over basic vocabulary (not just toponyms or names).

- Shared irregular morphology that resists areal borrowing.

- Robust comparative reconstructions that yield plausible proto-forms beyond Basque itself.

Absence of such evidence keeps Basque in the isolate category operationally.

FAQ#

Q1. Is Basque related to Aquitanian?

A: Yes—Aquitanian names show clear correspondence to Proto-Basque reconstructions, making it the closest extrinsic relative, but this does not extend to a broader family. 2

Q2. Could Basque ever be linked to Indo-European languages?

A: Mainstream theory places Basque outside Indo-European; proposed connections (including Iberian links) lack the comparative evidence required for genetic grouping. 7

Q3. Do typological similarities count as genetic evidence?

A: No—typological resemblance (e.g., ergativity) can arise independently or through contact, and therefore does not constitute proof of genetic relation. 8

Q4. Does Basque influence surrounding languages?

A: Substrate effects in early Romance (e.g., toponymy and phonology) suggest contact influence, but again this is areal influence, not evidence of common descent. 7

Sources#

- “Basque language,” Wikipedia (2025) — Basque as isolate and its context. 1

- “What is the Basque language?” Etxepare Institute — Basque isolate status and history. 8

- “Proto-Basque language,” Wikipedia — Proto-Basque and ancestral linkage. 2

- “Vasconic substrate hypothesis,” Wikipedia — Vasconic family proposal. 3

- “Late Basquisation,” Wikipedia — Migration/contact hypothesis. 4

- “What’s so special about the Basque language?” Lingoblog — survey of fringe relatives. 5

- L. Campbell, Language Isolates and Their History — isolate definition (BLS). 6