ملخص

- يؤثر الكروموسوم Y، إلى جانب تحديد الجنس، على الإدراك البشري، وخصوصًا الإدراك الاجتماعي، جزئيًا عبر الجينات المعبر عنها في الدماغ.

- تكشف حالات اختلال الصيغة الصبغية للكروموسومات الجنسية (مثل XYY) عن تأثيرات جرعة الكروموسوم Y على خطر التطور العصبي (مثل التوحد) التي تختلف عن تأثيرات جرعة الكروموسوم X.

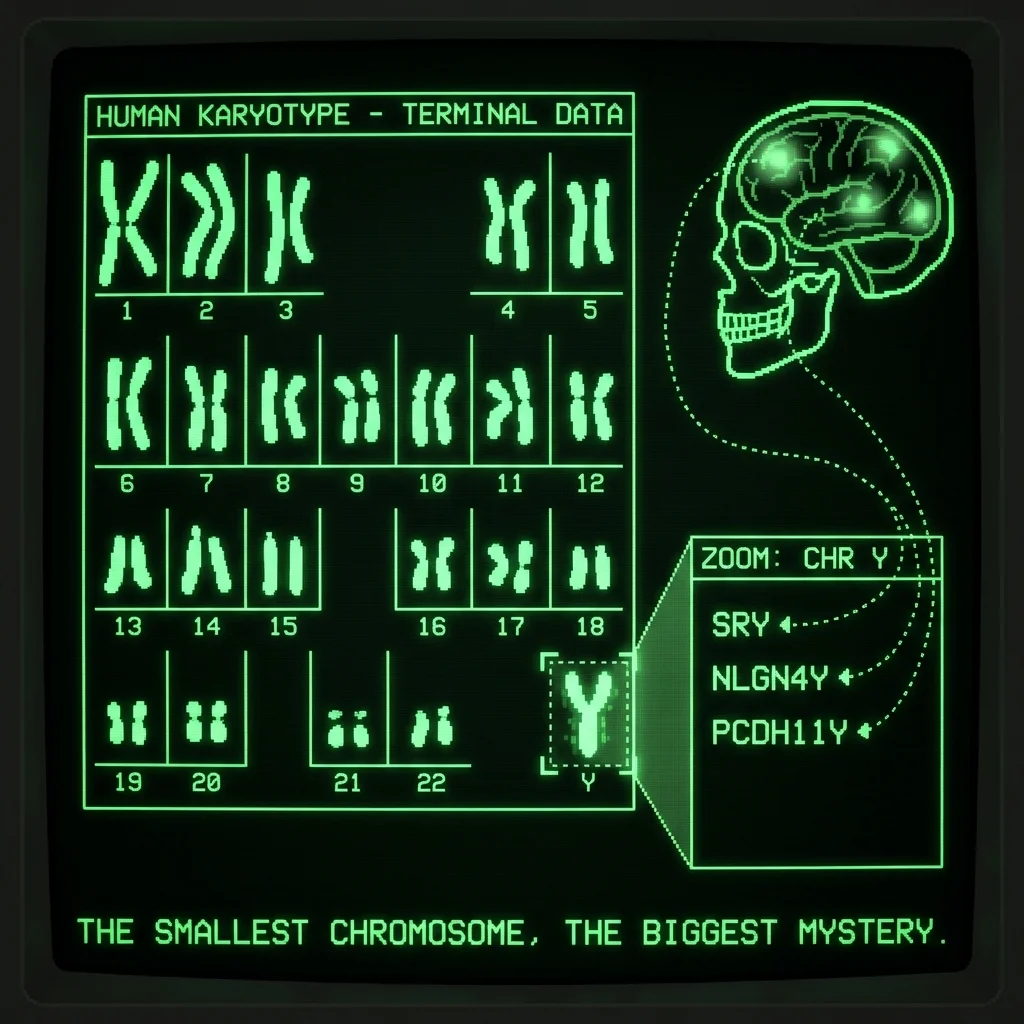

- تساهم الجينات المرتبطة بالكروموسوم Y (مثل NLGN4Y، PCDH11Y، SRY) وأزواج الجينات X-Y في تطور الدماغ، ووظيفة المشابك العصبية، وربما تطور الإدراك.

- يبرز التاريخ التطوري للكروموسوم Y والتداخل بين التعبير الجيني في الخصية والدماغ دوره المعقد في تشكيل البيولوجيا العصبية للذكور.

المقدمة#

تم التعرف الآن على أن الكروموسوم Y البشري، الذي كان يُعتبر سابقًا أرضًا قاحلة جينيًا، يؤثر على الفروق البيولوجية بما يتجاوز تحديد الجنس. بينما يحمل الكروموسوم Y عددًا قليلاً نسبيًا من الجينات (~60 جينًا مشفرًا للبروتين)، فإن العديد منها له وظائف حيوية محفوظة عبر التطور. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن العديد من الجينات المرتبطة بالكروموسوم Y يتم التعبير عنها في الدماغ النامي، مما يشير إلى أدوار مباشرة في التطور العصبي بالإضافة إلى التأثيرات الهرمونية غير المباشرة. يظهر الإدراك الاجتماعي العالي المستوى (مثل نظرية العقل، الوعي الذاتي، المعالجة الاجتماعية-العاطفية) انحيازات جنسية معروفة جيدًا (حيث تتفوق الإناث غالبًا في التعاطف والإدراك الاجتماعي، بينما يكون الذكور ممثلين بشكل زائد في التوحد). تجمع هذه المراجعة الأدلة من علم الوراثة العصبية، الجينوميات المقارنة، التصوير العصبي، الطب النفسي، وعلم الأحياء التطوري حول كيفية مساهمة الكروموسوم Y في هذه الفروق الإدراكية. نركز على الجينات المرتبطة بالكروموسوم Y ذات التأثيرات المتعددة على التكاثر والدماغ، وتأثير جرعة الكروموسومات الجنسية على بنية الدماغ، والأحداث التطورية (مثل تباعد أزواج الجينات X-Y واستبدال كروموسومات Y للنياندرتال) التي تسلط الضوء على دور الكروموسوم Y في تطور الإدراك البشري.

مساهمات الكروموسوم Y في الاضطرابات العصبية التطورية#

تشير أدلة مثيرة للاهتمام إلى تأثيرات الكروموسوم Y على الإدراك تأتي من الاضطرابات العصبية التطورية ذات الانتشار المتحيز جنسيًا. يؤثر اضطراب طيف التوحد (ASD) على ~4 ذكور لكل أنثى، ويظهر الفصام انحيازات ذكورية طفيفة في سن الظهور وملامح الأعراض. تاريخيًا، كان يُعزى هذا الانحراف إلى الطفرات المرتبطة بالكروموسوم X أو الفروق الهرمونية، لكن الأدلة الناشئة تشير إلى أن العوامل المرتبطة بالكروموسوم Y تلعب أيضًا دورًا. على سبيل المثال، حمل كروموسوم Y إضافي (النمط النووي 47,XYY) يزيد بشكل ملحوظ من خطر ASD مقارنة بكروموسوم X إضافي (متلازمة كلاينفلتر 47,XXY): وجدت دراسة أن تشخيصات التوحد في 19% من الأولاد مع XYY مقابل 11% مع XXY (مقابل ~1% في السكان العامين). أظهرت مجموعة أخرى أن ~14% من الذكور XYY يلبون معايير ASD الكاملة، مع العديد من الآخرين يظهرون إعاقات اجتماعية-تواصلية دون السريرية. على النقيض من ذلك، يعاني الذكور XXY من عيوب اجتماعية أخف ومعدلات أعلى نسبيًا من اضطرابات القلق/المزاج. أكدت مقارنة حديثة للتوصيف العميق أن XYY يفرض مشاكل اجتماعية-إدراكية غير متناسبة (مثل ضعف التواصل الاجتماعي والمزيد من السلوكيات المتكررة) مقارنة بـ XXY. تشير هذه النتائج إلى أن جرعة الكروموسوم Y تؤثر بشكل خاص على تطور الدماغ الاجتماعي.

الجدول 1 - الملامح الإدراكية/النفسية في حالات اختلال الصيغة الصبغية للكروموسومات الجنسية (أبرز النقاط المختارة):#

| النمط النووي (مكمل الكروموسومات الجنسية) | الميزات الإدراكية/السلوكية الرئيسية | العوامل الجينية البارزة |

|---|---|---|

| 45,X (متلازمة تيرنر) – أنثى بكروموسوم X واحد (بدون Y) | ذكاء متوسط ولكن عجز في الإدراك الاجتماعي (مثل التعرف على العواطف، معالجة النظرات) والمهام المكانية؛ ارتفاع معدل مشاكل التكيف الاجتماعي وبعض السمات الشبيهة بالتوحد، خاصة إذا كان الكروموسوم X الوحيد من الأم. | فقدان كروموسوم X ثاني – لا سيما فقدان كروموسوم X الأبوي يمكن أن يحرم الفرد من موقع مرتبط بالكروموسوم X مطبوع للإدراك الاجتماعي (يتم التعبير عنه عادةً فقط من كروموسوم X الأب). يتم تقليل عدد الجينات “الهاربة” من X (الجينات الحساسة للجرعة التي تهرب من تعطيل X)، مما قد يؤثر على التطور العصبي. |

| 47,XXY (متلازمة كلاينفلتر) - ذكر بكروموسوم X إضافي | إعاقة ذهنية خفيفة أو صعوبات تعلم في بعض الحالات؛ تأخيرات لغوية، معدل ذكاء لفظي أقل، وصعوبات في القراءة شائعة. غالبًا ما يكونون خجولين أو منعزلين اجتماعيًا، مع أعراض داخلية مرتفعة (القلق/الاكتئاب). يتم تشخيص ASD في ~10 - 15%. | كروموسوم X إضافي (معطل إلى حد كبير) يضاعف التعبير عن بعض جينات الهروب من X (مثل KDM6A، EIF2S3X)، مما قد يزعج التطور العصبي. يمكن أن يؤثر انخفاض هرمون التستوستيرون قبل الولادة وكروموسوم X غير نشط (جسم بار) في كل خلية بشكل غير مباشر على تنظيم الدماغ. |

| 47,XYY - ذكر بكروموسوم Y إضافي | خطر تطور عصبي مرتفع: في المتوسط معدل ذكاء أقل قليلاً وتأخيرات أكثر في اللغة والقراءة. عيوب بارزة في المهارات الاجتماعية-التواصلية (اللغة البراغماتية، التعرف على العواطف). زيادة في السلوكيات الخارجية (ADHD، الاندفاعية) ومعدلات تشخيص ASD ~15 - 20% - أعلى بكثير من XXY. | يعزز كروموسوم Y إضافي جرعة الجينات المرتبطة بالكروموسوم Y (العديد منها معبر عنه في الدماغ - انظر أدناه). من الجدير بالذكر أن تكرار NLGN4Y (النيرولوجين المرتبط بالكروموسوم Y) يُفترض أنه يساهم في الميزات التوحدية. عدم وجود كروموسوم X ثاني يعني عدم التعويض عبر جينات الهروب من X. قد تؤثر التأثيرات التنظيمية الخاصة بـ Y (مثل الهيتروكروماتين الخاص بـ Y أو ncRNAs المشفرة بواسطة Y) بشكل واسع على شبكات الجينات في الدماغ الاجتماعي. |

رؤية مفاهيمية: توضح “التجارب الطبيعية” المذكورة أعلاه أن الكروموسوم Y له تأثيرات فريدة على ملامح الأمراض النفسية. إضافة Y (XYY) تزيد من عيوب الإدراك الاجتماعي وخطر ASD أكثر من إضافة X (XXY). إزالة Y (تيرنر 45,X) في جينوم أنثوي بخلاف ذلك تضعف الإدراك الاجتماعي على الرغم من الهرمونات الأنثوية النموذجية. معًا، تشير هذه الأنماط إلى تأثير عمل الجينات المرتبطة بالكروموسوم Y (وتفاعلاتها مع جرعة X) في تشكيل الدوائر العصبية للسلوك الاجتماعي.

الجينات المرتبطة بالكروموسوم Y التي تؤثر على الدماغ الاجتماعي#

أي الجينات المرتبطة بالكروموسوم Y قد تكون وراء هذه التأثيرات العصبية الإدراكية؟ تبرز فئتان: (1) أزواج الجينات X – Y حيث قد يعدل النظير المرتبط بالكروموسوم Y العمليات الدماغية التي تحكمها أيضًا الجين المرتبط بالكروموسوم X؛ و(2) الجينات الخاصة بالذكور المرتبطة بالكروموسوم Y ذات الأدوار المتعددة في الخصيتين والدماغ.

النيرولوجينات (NLGN4X/Y)#

النيرولوجينات هي جزيئات التصاق الخلايا المشبكية؛ تسبب الطفرات في NLGN4X (المتعلقة بالكروموسوم X) التوحد والإعاقة الذهنية في الذكور. يحمل الكروموسوم Y نظيرًا NLGN4Y، ~97% متطابق في التسلسل. بينما كان يُعتقد أن NLGN4Y غير نشط إلى حد كبير، تشير الأدلة الجديدة إلى أنه قد يساهم في وظيفة المشابك – أو الخلل الوظيفي عند الإفراط في التعبير. على سبيل المثال، يظهر الأولاد مع XYY (نسختان من NLGN4Y بالإضافة إلى واحدة من NLGN4X) سمات توحد أعلى، وي correlates with ASD features. One hypothesis is that excess neuroligin-4Y upsets the excitatory – inhibitory synapse balance or interferes with neuroligin-4X function. However, biochemical studies indicate NLGN4Y may produce a truncated protein that is less stable, so its exact neural role remains under investigation. Nonetheless, the NLGN4X/Y pair exemplifies how a Y gene can influence male-specific risk for disorders like autism by (imperfectly) duplicating an X-linked neural gene.

Protocadherin 11X/Y (PCDH11X/Y)#

This gene pair arose from a duplication ~6 million years ago after the human – chimpanzee split. PCDH11X (on Xq21.3) and PCDH11Y (on Yp11.2) encode cell adhesion proteins of the δ-protocadherin family, highly expressed in the developing cerebral cortex (ventricular zone, subplate, cortical plate). They interact with β-catenin, a key regulator of cortical development and hemispheric patterning. Intriguingly, Crow and colleagues proposed that PCDH11X/Y drive the human-specific bias for brain asymmetry and handedness – the so-called “right shift” toward left-hemisphere language dominance. Accelerated evolution of PCDH11Y (which has no counterpart in apes) may have contributed to the neural substrate for language in Homo sapiens. However, searches for PCDH11Y variants in schizophrenia or other psychiatric disorders have not yielded consistent associations. It remains plausible that this X – Y gene pair set up a subtle sex difference in cortical connectivity or lateralization relevant to communication. In summary, PCDH11X/Y exemplifies an evolutionarily novel Y gene potentially tied to higher-order cognition (language and lateralized social brain functions).

Histone Modifiers (UTX/UTY and JARID1C/JARID1D)#

Many X – Y gene pairs encode chromatin regulators that could influence neurodevelopment. KDM6A (alias UTX) on X is a histone demethylase that escapes X-inactivation (females have two active copies), whereas its Y homolog UTY has retained enzymatic activity albeit weaker. Similarly, KDM5C (JARID1C) on X (mutations of which cause X-linked intellectual disability) has a Y partner KDM5D. These Y genes likely help buffer dosage differences in males, ensuring one functional copy is present since females effectively have two. In the brain, such epigenetic enzymes regulate cascades of gene expression. If UTY or KDM5D functionally diverges from its X counterpart, that could lead to sex-biased neural outcomes. For example, loss of one KDM6A copy (as in Turner syndrome) or its reduced activity in males might alter the expression of autism- or schizophrenia-related genes. Indeed, KDM6A is highly expressed in brain and has been implicated in syndromic ASD, whereas UTY shows more restricted expression but might still modulate key developmental genes. The combined influence of such dosage-sensitive X – Y pairs likely contributes to sex differences in brain development – an area of active research.

SRY and Male-Specific Gene Networks#

The master sex-determining gene SRY (Yp11) not only orchestrates testes formation, but is also expressed in the human brain (e.g. hypothalamus, frontal and temporal cortex). In rodent models, SRY is notably present in dopamine neurons of the midbrain (substantia nigra and VTA). Remarkably, SRY protein can bind and upregulate the promoter of Tyrosine Hydroxylase (the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis), enhancing dopamine production in males. Experimental knockdown of Sry in male rats causes loss of dopamine neurons and motor deficits, mimicking Parkinson-like features. This suggests SRY helps “masculinize” certain neuromodulatory systems, possibly contributing to sex differences in dopamine-linked behaviors (e.g. reward processing, motor activity, attention). Beyond dopamine, SRY influences other neurochemical systems: for instance, it modulates vasopressin-expressing cells in the septum (affecting social memory and aggression). Intriguingly, a recent network analysis of SRY and its ancestral analog SOX3 found that SRY-specific target genes are enriched for roles in neurodevelopment and may contribute to the male bias in autism. In other words, SRY’s regulatory program in the male brain might tip the balance toward ASD risk by altering developmental timing or connectivity of social circuits. These findings exemplify how a male-limited transcription factor can shape brain phenotype beyond its gonadal functions.

Ampliconic and Germline Y Genes in the Brain#

The Y chromosome’s ampliconic regions (e.g. AZF regions important for spermatogenesis) contain multi-copy genes traditionally thought to act only in testes. Surprisingly, several of these have been detected in the brain or during neural differentiation. A transcriptomic study of a male human stem cell model found that as embryonic cells differentiate into neurons, a suite of 12 Y-linked genes become significantly upregulated, including RBMY1 (RNA-binding motif protein, Y-linked), HSFY (heat shock factor Y), BPY2 (basic protein Y-2), CDY (chromodomain Y), USP9Y, DDX3Y, EIF1AY, ZFY, UTY, RPS4Y1, PRY, and SRY. Many of these have X counterparts involved in RNA processing or protein synthesis. For example, DDX3Y (in AZFa) encodes a DEAD-box RNA helicase required for spermatogonial development – but also appears critical for neural progenitors: knocking down DDX3Y in developing neural cells impairs cell-cycle progression and increases apoptosis, disrupting neuronal differentiation. This reveals a pleiotropic role: Y genes like DDX3Y are needed for both sperm production and neuron production. Likewise, RBMY1 (a spermatogenic RNA-binding protein) has an X homolog RBMX that is essential for neuronal survival; it’s plausible RBMY transcripts in early brain help regulate neuron-specific splicing programs. These examples illustrate a broader principle: the testis and brain share an overlap of gene expression – in fact, among human tissues, the brain and testis have one of the highest similarities in gene expression profiles. Evolution may have favored using the same genetic toolkit in both tissues (perhaps because both require rapid protein synthesis, complex cell-cell interactions, and unique gene products). As a result, Y-linked genes under selection for male fertility may carry “incidental” effects on the brain (and vice versa). This could explain why mutations or copy-number variations in certain Y genes can impact both reproductive and cognitive traits.

Sex Chromosome Dosage, Brain Scaling, and Social Circuitry#

Beyond individual genes, the dosage of sex chromosomes as a whole influences brain structure and function. Studies of sex chromosome aneuploidy and normative sex differences point to coordinated effects on brain anatomy. Notably, Armin Raznahan and colleagues have shown that increasing sex chromosome dosage (counting X+Y chromosomes beyond the typical two) produces region-specific changes in cortical architecture. In a large MRI study spanning 46,XY males, 46,XX females, and subjects with 45,X, 47,XXY, 47,XYY, etc., mounting sex chromosome dosage was associated with thickening of cortex in frontal regions and thinning of cortex in bilateral temporal regions. The affected zones – rostral frontal cortex (including medial/orbitofrontal areas) and lateral temporal cortex – are precisely areas implicated in social cognition and language processing. In other words, sex chromosome dosage exerts a systematic “push-pull” on brain morphology: higher dosage (e.g. XXY or XYY vs. XY) tends to enlarge frontal social brain regions but shrink temporal language regions. Importantly, these anatomical shifts align with functional networks: regions most sensitive to sex chromosomes show strong inter-correlations (covariance) in typical brains, suggesting the sex chromosomes modulate a connected neural system.

Figure Description: Sex chromosome dosage effects on cortical structure: In a large MRI study of sex chromosome aneuploidies, researchers identified specific cortical regions where increasing X+Y dosage consistently altered thickness. Left: Regions in medial frontal cortex (yellow/red) gain thickness with each additional sex chromosome. These areas are involved in social and emotional cognition (e.g. theory of mind, self-referential thought). Right: Regions in lateral temporal cortex (blue) lose thickness as sex chromosome count rises. These areas subserve language and social perception (e.g. processing facial cues, speech). This frontal – temporal pattern suggests a dosage-sensitive scaling of circuits crucial for higher-order social cognition.

Why might sex chromosomes scale the cortex in this way? One possibility is gene dosage imbalance: X-linked genes that escape inactivation (or pseudoautosomal genes) are more expressed in XX vs XY brains, whereas Y-linked gene copies exist only in males. For instance, female (XX) brains get a double dose of KDM6A and EIF2S3X (which escape silencing), potentially favoring certain developmental pathways, while male (XY) brains have unique expression of Y genes like NLGN4Y or TBL1Y. These differences could bias neural progenitor proliferation or synaptic pruning rates regionally. Another factor is the nuclear architectural impact: females have a silenced X (Barr body) in each cell, adding a lump of heterochromatin, whereas males do not – this could subtly influence 3D genome organization and gene expression programs in neurons. Indeed, XXY cells (with one Barr body) and XYY cells (no Barr body, but extra Y heterochromatin) present different nuclear environments. Such effects might concentrate in specific cortical regions that are most developmentally plastic or gene-expression-rich (like association cortices). Moreover, sex-biased gene networks likely orchestrate region-specific development: for example, genes involved in language cortex development (FOXP2 targets, etc.) may be dosage-sensitive to X escapees, whereas those in orbitofrontal development may respond to Y-linked factors (like SRY-related modulation of neurotrophic signals). While the exact molecular drivers are still being untangled, the consistent pattern of cortical remodeling with sex chromosome dosage underscores that the X and Y chromosomes collectively shape the anatomical substrate for social cognition.

Evolutionary Perspectives: Y Chromosome History and Cognition#

The human Y chromosome has a peculiar evolutionary trajectory that intersects with cognitive evolution in surprising ways. Sex chromosomes originated ~150 - 200 million years ago in mammals and have been degrading and rearranging since. In primates, the Y shed most of its original genes, retaining a set of essential genes (often with X homologs) and acquiring some new male-specific genes. The genes preserved on the human Y are there for a reason – many are dosage-critical “housekeepers” (e.g. regulators of transcription/translation needed in all cells) or have roles in spermatogenesis. It is likely not a coincidence that many Y-conserved genes are expressed in brain and other vital organs (e.g. USP9Y, DDX3Y, EIF1AY, RPS4Y1, ZFY in blood and brain ) – if they were dispensable for somatic functions, they might have been lost. The implication is that across evolution, the Y’s remaining genes had to pull double-duty, contributing to fitness in both reproduction and perhaps neural function.

One dramatic chapter in Y chromosome evolution is the apparent replacement of Neanderthal Y chromosomes by those of modern humans. Genomic analyses indicate that when Homo sapiens interbred with Neanderthals (~50,000 – 100,000 years ago), the Neanderthal Y chromosome did not persist in the hybrid populations. Instead, modern human Y chromosomes swept through Neanderthal groups, eventually rendering the Neanderthal Y extinct. Researchers speculate this was due to incompatibilities or disadvantages of the Neanderthal Y. For example, the Neanderthal Y may have harbored alleles that triggered immune attacks from H. sapiens mothers, leading to miscarriages of male hybrids. Indeed, one Neanderthal Y gene variant is known to provoke transplant rejection in modern humans, hinting at a genetic incompatibility that could affect pregnancy. Another theory is that Neanderthals’ long isolation and smaller population size led to accumulation of deleterious mutations on the Y, weakening male fertility. Early modern humans, coming from a larger gene pool, carried a “fitter” Y chromosome that, when introduced via male sapiens – female Neanderthal pairings, conferred a slight reproductive advantage. Over thousands of years, this advantage would result in Neanderthal Y being entirely replaced by modern Y in the Neanderthal genome.

What are the implications for cognition? While the driving factors were likely immunological or reproductive, one can speculate that genes on the modern human Y (absent or different in Neanderthals) might have also affected brain function. It is intriguing that Neanderthals, despite having similar brain sizes to modern humans, left a slimmer cultural and technological record. Could a subtle genetic factor – perhaps a Y-linked gene regulating neural plasticity or social behavior – have played a part? This remains speculative, but consider that PCDH11Y, the protocadherin linked to brain asymmetry, is unique to modern humans (arising after the Homo – Pan divergence and thus present in Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, but possibly differing in sequence). If a mutation on PCDH11Y (or another Y gene like USP9Y or TSPY) improved social cognition or communication in early modern humans, it might have conferred an edge. More concretely, the Y chromosome’s evolution reflects repeated selective sweeps that likely influenced male traits: for instance, the high conservation of certain Y genes suggests purifying selection for functions that could include neural development. The loss of the Neanderthal Y underscores how critical those Y genes are – any incompatibility was not tolerated. Thus, while we cannot ascribe human cognitive supremacy to the Y chromosome, it is a piece of the evolutionary puzzle. The modern human Y may have been optimized (purging harmful variants) in ways that indirectly benefitted brain health and development of its carriers, contributing to our species’ resilience and perhaps social complexity.

Shared Genetic Architecture: Testis – Brain Overlap and Y-Linked Pleiotropy#

One recurring theme is the shared molecular programs of the brain and testes, two organs that at first glance have little in common. Both undergo bursts of gene expression and cell differentiation (brain during development, testes continuously in spermatogenesis) and both express a wide variety of genes – indeed, global transcriptome analyses show that human testis and brain share the greatest similarity in gene expression patterns among tissues. Many genes highly expressed in testis (e.g. for meiosis, cell-cell adhesion in germ cells) are also expressed in certain brain cells (neurons or glia) – a classic example is the neuroligin and neurexin families involved in synaptic adhesion, which were first studied for roles in the brain but also have testis-specific isoforms. This overlap means that natural selection on males can lead to pleiotropic effects: a genetic change to improve fertility could inadvertently affect the brain, or vice versa. The Y chromosome, being male-specific, is a hotspot for such pleiotropy.

We have already seen cases like DDX3Y, where a Y gene necessary for sperm production also impacts neuron generation. Another example is the RBMY gene family: these RNA-binding proteins are required for proper sperm development (mutations cause azoospermia), yet RBMY is expressed in early brain development and some studies suggest it might influence neuronal RNA splicing. TSPY (testis-specific protein Y) is another multicopy Y gene expressed abundantly in testes; intriguingly, TSPY has been detected in certain brain tumors and is thought to promote cell proliferation (consistent with a role in driving spermatogonia mitosis). While normal brain expression of TSPY is low, its mere presence shows how the Y’s testis-focused genes can find their way into other contexts.

This principle of testis – brain overlap extends to disease genetics: Y-linked mutations or anomalies often present with both reproductive and neuropsychiatric effects. For instance, men with Y microdeletions in the AZF regions (who have infertility) may have higher rates of learning disabilities or developmental delays than expected, although data are limited. Likewise, the high prevalence of neurodevelopmental diagnoses in XYY and XXY syndromes (discussed earlier) highlights how adding extra “fertility genes” (like additional copies of RBMY1 or DAZ) can perturb brain development. In XXY Klinefelter, genes that normally escape X-inactivation (such as STS – steroid sulfatase, or NLGN4X) are overexpressed and could lead to subtle brain differences (e.g. altered myelination or synapse formation) that manifest as cognitive phenotypes. Conversely, the absence of a second X in Turner syndrome means reduced dosage of those escapees, which likely contributes to the social cognition deficits in 45,X females.

In summary, the Y chromosome’s role in cognition cannot be viewed in isolation – it is part of a larger sex-chromosomal gene network acting on the brain. The Y provides male-specific inputs (SRY, etc.), while the X provides dosage-sensitive inputs; together they modulate developmental pathways for brain regions critical to social behavior, language, and emotion. The evidence reviewed here – from aneuploidy studies to gene expression analyses and comparative genomics – converges on the idea that the Y chromosome, though diminutive, exerts an outsized influence on the social brain. It does so via both direct gene action (e.g. Y genes expressed in neurons) and indirect mechanisms (e.g. interacting with X gene dosage or hormones).

Conclusion#

Far from being a genetic bystander, the Y chromosome emerges as a subtle orchestrator of sex-biased neurobiology. Its genes – relics of our evolutionary past and drivers of male development – thread into the tapestry of the brain’s growth, especially in circuits governing social cognition and behavior. The ampliconic regions of the Y, once thought limited to spermatogenesis, likely harbor factors that incidentally sculpt neural development. Meanwhile, X – Y gene pairs ensure that males and females achieve balanced expression of critical genes, with imbalances contributing to disorders like autism when the system is perturbed. The evolutionary history of the Y, including events like the Neanderthal Y replacement, underscores the strong selective pressures on this chromosome that may have also shaped our cognitive lineage.

For researchers in cognitive science, genetics, and evolutionary neurobiology, the challenge moving forward is to pinpoint the molecular mechanisms by which Y-linked genes influence brain development and function. This will involve integrative approaches: linking human neuroimaging findings (e.g. cortical thinning in XYY) to molecular genetics (e.g. which Y genes drive those effects), leveraging animal models with manipulated sex chromosomes (e.g. the “four core genotypes” mouse model separating hormonal and chromosomal effects), and studying gene expression at single-cell resolution in male vs female brain tissue. Another intriguing avenue is the study of Y chromosome mosaicism in aging – loss of the Y in blood cells has been linked to Alzheimer’s risk in men, hinting that Y gene function might even impact neurodegeneration and immune interactions in the brain.

In conclusion, the Y chromosome, despite its modest gene content, plays a multi-faceted role in human cognition. It contributes to the sexual differentiation of the brain both directly (through Y-specific gene activity in neurons) and indirectly (via interactions with the X and hormone systems). Its genes can be gatekeepers of critical developmental processes, as seen in their dual roles in testis and brain. And through evolutionary time, the Y has been molded by forces that likely also influenced cognitive traits in subtle ways. Unraveling this Y-linked neurogenetic tapestry will not only deepen our understanding of sex differences in cognition and psychiatric disorders, but also shed light on the unique trajectory of human brain evolution.

المصادر#

- Raznahan et al., Globally Divergent but Locally Convergent X- and Y-Chromosome Influences on Cortical Development (2016)

- Skuse et al., Evidence from Turner’s syndrome of an imprinted X-linked locus affecting cognitive function (1997)

- Greenberg et al., Sex differences in social cognition and the role of the sex chromosomes: a study of Turner syndrome and Klinefelter syndrome (2017)

- Lai et al., Sex/gender differences and autism: setting the scene for future research (2015)

- Crow, T.J., The ‘big bang’ theory of the origin of psychosis and the faculty of language (2006)

- Williams et al., Accelerated evolution of Protocadherin11X/Y: A candidate gene-pair for cerebral asymmetry and language (2006)

- Hughes et al., Strict evolutionary conservation followed rapid gene loss on human and rhesus Y chromosomes (2012)

- Case et al., Consequences of Y chromosome microdeletions beyond male infertility: abnormal phenotypes and partial deletions (2019)

- Sato et al., The role of the Y chromosome in brain function (2010)

- Morris et al., Neurodevelopmental disorders in XYY syndrome: 1. Comparing XYY with XXY (2018)

- Mastrominico et al., Brain expression of DDX3Y, a multi-functional Y-linked gene (2020)

- Mendez et al., Y-chromosome from early modern humans replaced Neanderthal Y (2016) - Overview

- Wijchers & Festenstein, Epigenetic regulation of autosomal gene expression by sex chromosomes (2011)